Lit Mags

A Story About a Parasitic Relationship

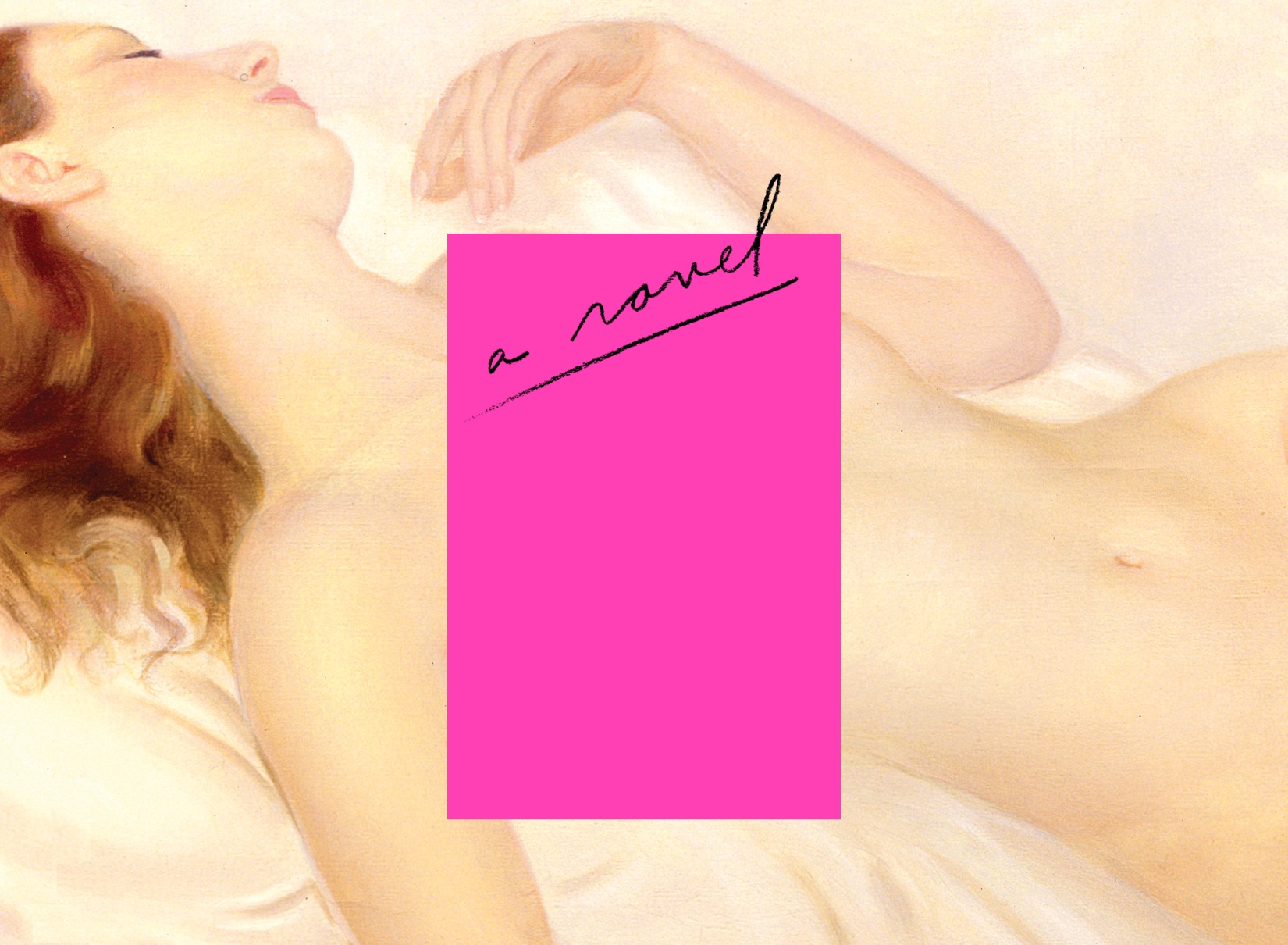

“Together” by Jess Arndt

AN INTRODUCTION BY JUSTIN TORRES

Jess Arndt is a great prose stylist — but what does that mean? Well for one thing, it means Arndt writes with such poetry and such precision, that the force of the communication damn near knocks you over. The sentences turn, open, and crash down on you unexpectedly, rhythmically, like waves. Great style has something to do with surfaces, but that’s not all I mean when I say Arndt is a great stylist. I mean, too, that the pace and pull of this story — and really, every story in Large Animals — works something like an undertow. At the beach as child, I remember being warned about undertow and thinking, how could it be, amidst all the foam and roar and sparkle of the ocean’s surface, that an even stronger churning went on below? But that’s exactly the experience of reading Arndt: first mesmerized by the beautiful noise of the language, then knocked down, and dragged out to another, underwater world.

“Together” is a story precisely about the churning going on beneath the surface — about the awful lot going on inside each of us. Arndt reminds us that physically, psychically, we are processes; we are happening all the time. The life of both mind and body is defined by an awesome and constant churning. And outside, in our backyards, our neighborhoods, our neighbors, our lovers and bosses — the churning continues. Places and people seduce, destroy, remake us in their undertow. What we would like to understand as form — the backyard, the body — is phenomena. What we would like to understand as impermeable is always susceptible to parasitic invasion. Instability is the shared condition of life. This is a thing we know, but the knowledge quickly stales, or we are distracted from the knowledge, or narcotized, or placated with straighter, more genteel notions.

I can think of no better description for the transformative power of Arndt’s stories — willful.

Reading Arndt, I was reminded of Genet, and reminded specifically of Sontag’s description of Genet, in “On Style.” “He is recording, devouring, transfiguring his experience. In Genet’s books, as it happens, this very process itself is his explicit subject; his books are not only works of art but works about art.” Sontag goes on to connect style, above all, to will: “The complex kind of willing that is embodied, and communicated, in a work of art both abolishes the world and encounters it in an extraordinary intense and specialized way.” I can think of no better description for the transformative power of Arndt’s stories — willful. I suppose it’s a particular kind of lineage, a particular kind of will I’m getting at, when talking about Sontag talking about Genet, and also talking about Arndt — I suppose it’s something like the will of the lover, the will of the parasite, the will of the undertow; I suppose I am talking about the will to queer the world.

Justin Torres

Author of We the Animals

A Story About a Parasitic Relationship

Jess Arndt

Share article

“Together”

by Jess Arndt

We had it together but we also had it when we were apart. We got it in that comedor in Oaxaca, we both agreed. Or maybe it was that little town, just a few palapas actually and a beach with a deceptive number of black dogs, called San Angelino. But it’s also quite possible that we had gotten it on the subway. Don’t forget about a head of lettuce! our naturopath said. They caravan those heads in from anywhere imaginable. And water these days — it’s no good washing with it.

We made a list of what was now okay and what wasn’t. Sugar, yeast, all the essentials — out. Enter: lines and lines of herbaceous esophagus-jamming pills we swallowed noon dinner and night.

“It’s not so bad,” you said. “We weren’t into that kind of junk anyway.”

But who could tell? What we were and weren’t into? For instance, Bloody Marys at Giondo’s, what about that? And occupation politics — was it possible our parasite was affecting those too? Before, we’d been heavily committed: gotten arrested even, clubbed by the militia-era NYPD.

“Let’s take it back to where it came from,” you said. “Niagara Falls or the Jurassic period or what about that town you like, Boring, Oregon? It really feels like it came from there.”

What we shared had sticktuitiveness. You had to give it that.

When we looked it up online the definition said: “one who eats at the table of another,” which seemed kind of cordial, so 1950s, like a neighbor plus misshapen apple pie dropping by.

But who had neighbors like that?

Ours were more like that guy we knew, Raif, who on his way home sloppily inserted himself into our kitchen, slogging through our sole bottle of scotch, probably shoveling coke up off the back of our toilet seat without offering any, probably crying even — before wheeling away again into the splashes of light and dark, the leafy trees and trash that made up our block.

We had it together, this relative of giardia partying in our now shared intestinal tract, but we reminded ourselves — we could have picked this thing up anywhere. The lack of fault was comforting. Plus the parasite wasn’t all. In our Greenpoint yard hard pink asparagus-like weeds were erupting everywhere, pubing skyward with a level of tenacity I no longer recognized.

When I was young I knew that everything was sentient and I was capable of great harm. Moreover, I knew that things should not be separated — that pairs, no matter where you found them, should stay intact. Under everyday pressure, that feeling had gone underground. Now, looking out at our yard, a spray of turf between the parallel avenues of McGuinness and Manhattan, it swam up again.

The stalks seemed so invincible, thrusting through the heavy metals and constant turnover of Popov bottles that made up our soil. Should I inject them with syringefuls of recently outlawed weed killer, as RAT574, my new buddy in the underground chat rooms, urged? The kind that gives everything gooey eyes? I could do it at night beneath the pale gray dome of light pollution we lived under.

Or what if I let the stalks showboat, have their time in the sun? Nothing else was growing.

“Make a choice,” you sighed. “I don’t care.” You’d been saying that a lot lately.

Still I was locked in an intractable standoff. It distracted me no end. I often stood on the pitched steps, dolefully. Then I would descend into the dirt and snap off their waist-high heads, pinching the magenta frill between my finger and thumb. That barely slowed them. Even pulling at them did no good. It was Japanese knotweed, and, as you liked explaining, their roots flanged out at the base like butt-plugs.

Around that time I got fired from the Baltic, a ramshackle tavern on a drifty block of Avenue C, left smoldering from an older, more terrifying era. It was huge, draped in once-regal green felt, with smoke stains that stippled the floors and ceiling like Sherwood Forest fungus.

“Too bad about that Big Fuck Up,” said my boss, Terry, a pleathery fag in white Keds. He shook my hand in a friendly way.

I’d been there for years, dutifully slinging Yuenglings. But I didn’t have the heart to fight for my job. I knew he was trying to get rid of us, his loyal few, so he could bottom for the Pinnacle Corporation. In the last month their goons had come around nonstop, checking the place out while Terry twisted them a fortune of cold beer.

I faced the barroom for the last time. Ooooh I feel good I feel good I feel good, said Donna Summer. Gerald sat on his stool with his long braid dangling behind him, drinking E&J. I walked over to him.

“Well,” I said.

He grimaced. He’d been tall but now his body was cinched up.

“I hate to go home,” he said. Gerald was stuck in the eighties. His nightmares were endless hospitals. I wedged a twenty under his glass snifter.

“Not tonight, pal,” I said. I wanted him to keep getting good and drunk.

“Try to remember,” I said, arranging his lapel. “We’re safe now.”

I stood on the Bowery platform and waited for the late-night J train. My gut yowled. Our parasite was a new and mysterious development. It was gross, but it gave us something to talk about. I glared warily at the track. Did everyone want to jump in front of the subway as much as I did? Not necessarily to die, although that was, of course, likely. Help! I’d shout. Someone would come. Still, once the thought occurred, it felt impossible to resist. Persuading myself that everyone was gripped by the same mania — a mania so regular it was boring — made it less awful when I shrunk from the inevitable approaching train, scrunching my eyes against the finishing blow.

That night I sat for a long time in the dark of our kitchen, looking past the window’s reflection, out into the yard. Then I went to bed as usual. Our apartment was so narrow it seemed as if we together were Jonah, inhabiting the “inner whale.” You’d disagree, scoffing into your hand: as early as 1520, Rondelet knew it wasn’t a whale but a Great White Shark, you’d say — but for once, you were sleeping quietly. Your job at the new pot shop was wearing you out.

“Can anyone really live in a shark?” I thought drowsily.

Then the Casio was flashing 3:47 and a voice was peeping up from the blankets, urging me awake.

I sat alert, staring at the tapered gloom. Pressing my hand to the wall for balance, I tried not to wake you. But focusing on your warm skin, I found myself in a panic.

Earlier, we’d fought.

You’re so full of shit your eyes are brown, I heard myself saying, a perennial favorite of my father’s. I’d followed it with something ridiculous, light-headed, unhinged even. You hadn’t responded. Was this why I’d stayed up so long, staring out? There was a new edge to everything, wasn’t there?

“Gabriel?” I said.

“Let’s begin,” the voice insisted.

My bladder thickened. You continued to sleep, coma-like.

I wriggled around you, clicked on the sound machine standby, “Gurgling Brook,” and crept into the also sloping kitchen. The boards were old, shards of gone forests. The Famous Grouse was capless on the table where I’d left it.

“Leon,” the voice said.

I stood there dimly and searched for its origin. In plain view was a giant mason jar of kombucha plus dividing mother. A pair of gunk-smeared garden gloves. An ancient Vogue with Tilda Swinton on the swanny-white cover.

“It’s me!” the voice said.

The room smelled like snapped pine needles. In my chest, a river was bludgeoning heavy stones.

“Ms. Swinton?” I stammered.

Her alien parts and cinnamon hair, I’d always loved her, the queasy look she gave me!

But the voice came from somewhere closer, near my belly.

“You have a problem,” the voice said.

I digested this halfway.

“I do?”

I thought hard. I pointed, finally, to the garden.

But our parasite disagreed.

“Do you know anything AT ALL,” it said, “about the history of Mexican art?”

When I woke again, a belt of sun was cinching my eyes. Your bare torso moved around the kitchen, pouring maté water, stretching. Outside silent cars were starting up their phony, pre-recorded engines. “Safety first!” an automated voice announced.

I raised my head from my cardboard arms. I’d finished the night at the table with Tilda. Turning my cheek, I followed your movement. Your darker areolas met the fawn of your chest with the casual kismet of belonging. I suffered to join their easy glow.

“So that’s it, I’m gone, blitzed, finally cooked,” I said instead.

Your nostrils tightened.

“What happened.”

“Gay bars are out!” I snapped my fingers to my thumb. I wanted to be back in your good graces but I resented working for it.

“Terry called,” you said. “Did you really do something as substantially dumb as that?”

I sighed. My relationship to right and wrong had always been murky. I had a healthy, some said Catholic approach to guilt. But in recent years I’d begun to wonder if my guilt was so all-encompassing as to be irrelevant to any motive or consequence. The realization stranded me without a barometer. It was clear, I didn’t trust myself with much. But I was also sure I could do no wrong. I toed every line almost religiously but was given to taking wild risks without any forethought at all, then, overcome with denial, hiding them.

“Gabriel,” I said, “Giga,” throwing my arms toward your waist.

“I have to go,” you said. “Work.”

A new relationship was being drawn. You worked. I didn’t.

I drifted around the apartment drinking expensive single-source coffee and clicking back and forth between Manhunt and my newest discovery, YardHard. The homepage was full of popups about “green bums” and “top tips for hoeing,” but RAT574 seemed to know something.

Him: Man knotweed is Axis of Evil numero uno. You got to be tenacious. Know how to spell that?

Me: You just did.

Him: Ok first let those suckers get big and hard. Then when they’re dick thick ? ? ? you machete o the tops RAMBO-style.

Sun was banking off the window, showing all the grease on the thin glass.

Got me???

I twisted on my stool, staring at the yard’s newest growths.

Got you.

Him: Then you dump your kill juice down the stalk. Kill juice? It seemed extreme.

Me: Can “kill juice” be organic?

Him: No way! Its got2be poison!

Me: . . .

Him: Great band by the way.

When I tried to remember why we’d fought, a gelatinous feeling descended. I was growing increasingly more wired from the caffeine plus somehow I was starving. The combo made me pharmaceutically woozy. Had our parasite, a microorganism who was leeching my precious nutrients, all those hard-earned dollars spent on kale and handpicked cashews, actually talked to me last night? Given me a lecture on art? I mean, there was Rivera of course, and Kahlo to be sure. But that was baby stuff. It was true, I knew next to nothing about Mexican art!

I depended on you to teach me things. Your father was a writer from the outskirts of Mexico City. Your mother was an engineer from Ottawa. You were the New North American: impervious — perfectly sealed off. That was why one night during our recent trip to Mexico, when we were refueling in central D.F., I wanted to go out alone. You were so chulo, so natural in the wide avenidas and plazas that nobody spoke to me and I was anxious to try out my Spanish.

“You stay here,” I begged. We had taken over your friend’s newly emptied Condesa apartment. “Go talk to your abuela or something.”

Your father was her baby, which made you in every way preferential.

“On the telephone?” you said, rolling your eyes. “It’s a big city, maricón.”

“I don’t know, eat flan then.”

I was suddenly desperate to be alone.

“Grow up,” you said. But instead of shoveling into your jacket you watched me go.

At noon it was time to take a Paradex from the naturopath. I grimaced and unscrewed the cap. Then I walked out into the yard. The season was changing. It would be light for hours and hours and hours. Pink shoots raved in the breeze, their heads glistening. They were much taller, already, since yesterday.

My feelings about objects had always been orphic — they penetrated my deepest levels. It was painful to be alive, I knew. Worse, I was somehow responsible. Undisturbed — walls, chairs, rocks, et cetera could fend for themselves. But my presence troubled the atmosphere. If, while walking, I kicked a rock but not the rock next to it, I created an imbalance, pointed at a wound. It then followed, it was the rule, that I turn around and similarly move the other rock. But what if I touched that second rock (it was bigger and so my toe needed more force to push it) longer than the first? Things were now severely out of whack.

“Sorry,” I’d whisper, retracting my foot at hyper-speed.

Small crises like these followed me everywhere I went. Throwing out a dirty chopstick if its mate was clean made me pause at the trash can like an awful, disloyal god. Other times, lone discarded shoes or cracked bathroom tiles leered out to me. Don’t notice them! I’d mutter. But their suffering was insistent.

Now my stomach gurgled but gave no further orders. Above me, a flight of molting pigeons swooped low. I juggled the pill anxiously. It was sweaty in my wintersoft palm. As if on auto-pilot, thinking about nothing, I used my thumb against the soil to dig a small indent. Then I plopped the dark gel cap in.

That night the clock dragged. You were late. I went to bed and kicked around. Our mattress felt like it was filled with overturned traffic cones. For half an hour, I read about Rufino Tamayo. What, I began to wonder, did our parasite think of his 1978 work La Gran Galaxia? In it the figure, who wore something like a jailbird’s smock, was staring over a bowl of sea. As if a mirage, the inner pink organelle of his body was reflected out, shimmering over the blue expanse, while above the horizon line, a luminous geometry of constellations flexed.

The figure appeared to be yawning.

In quick succession, I sent you some texts.

One said: Our parasite’s kicking, is yours?

No response. I continued.

I think I’m having contractions.

Silence. I switched tacks.

What’s eating you? ?

Tired of looking at an empty screen and the arrow that said slide to unlock, I turned off my phone.

I dreamed but my sleep was disturbed, watery. In it, I repeated a scene from my childhood. I had grown up near islands — rocky, fir-smothered pods on the north-northwest coast. As a kid I often accompanied my father in his boat.

One morning he woke me up early.

“There’s been a wreck,” he said.

We went down to Fidalgo Marina. Behind us, the sun simmered up over the Cascade range. The consensus among the boat owners was: Drunk Indians. There was a reef between the Lummi-owned Gooseberry Point and a local casino. During the night, a small Bayliner had hit it going full speed.

The men refilled their Styrofoam cups of coffee. Someone handed me one, topped to the brim. Drunk Indians. A no-brainer, everyone agreed. I was ten or eleven, newly effeminate. I liked to wear a solo rubber band in the back bud of my hair. I felt a chill and clutched my cup.

As the day went on, more news came in. There’d been six passengers, all still alive, but some were in pretty bad shape at Harborview and other trauma hospitals nearby. They’d been ejected forward from the boat, thrown like sacks onto the sharp rocks.

Toward evening my father let go of his usual German clamped lip. There weren’t any deliveries to make. He could be wily, even impish at times. He closed the engine compartment where he’d been slowly tinkering at the fuel lines.

“Let’s go,” he said.

We untied and cut out across the strait. I struggled to nice up the buoys. I loved helping my father and did it with a silent pride. But I was brimming with the idea of the wreck. Violent pictures filled my mind. I found myself searching the waves for a sign of tragedy. In all directions, there was nothing. The after- noon was calm and hot.

Then the small tan boat tilted into sight. It lay halfway across the reef, which was, at low tide, a dwarf island.

My father cut the engine and brought in our bow.

“Go on,” he said. “See what’s in it.”

I jumped onto the wreckage with a thud. Suddenly alone. I snooped as best I could. The category “Drunk Indians” dominated. I expected its presence to look fundamentally different from what my father and his brother did together with pails of Coors most nights. Fuck you, I muttered. Fuck you, fuck you. But here was no mess, no beer cans or incriminating plastic jug of booze. Just a small suitcase on the ripped-up fiberglass floor and the bracing zing of being this far away from land.

“Open it,” my father pressed, his voice still close to me.

I hesitated. Drugs, I thought. Big plastic bags of coke powder like I’d seen on TV. My imagination was limited. Money, Uzis.

We were trespassing but my father had his own law.

Queasy, I unzipped the stiff fabric and looked down. A stack of clean washcloths crouched in the web of the opening, starched and tightly folded. I poked them. Towels, shirts. The bag was immaculately packed with someone’s laundry, as if the person who owned it was going on a trip.

“Leon!” my father shouted.

The tide had flipped and the current was ripping sideways. Our bow dragged closer to the reef. We were a team; now he needed me. Dutifully, I hurdled aboard.

“What was it?” he said, as he slammed us into reverse. Freezing green water foamed over the transom.

“Nothing,” I reported, facing ahead.

But that night I was stricken.

I’m sorry, I said again and again to my lowering bedroom ceiling. I’d done doubly wrong. I’d pro ted from someone else’s bad time. But worse, what really concerned me, was that I’d left the bag abandoned with all that dark water surrounding it — the cloth open, its contents exposed.

I tried to tell you this once but you just shook your head.

“Your dad is nuts.”

Now it was almost midnight and very hot. I thought about the small graveyard, a day’s worth of pills, out in the yard. I fuddled with my phone’s screen. A picture of your face flashed up when I touched your name. Your hair was short and your jaw was feral.

I paused.

Is this about Mexico? I jabbed down onto the screen.

In the D.F., having left you, I walked toward the park that I remembered marking the center of Condesa. Earlier in the day kids had been playing soccer on the concrete monument. Next to the fountain stood a series of columns whose plinths were covered in vines that evoked a jungly snarl without actually being unkempt. Together we’d sipped cans of Bohemia in the sun.

The entire trip, you’d been trying to show me something — at least, I thought you had. In front of me Parque México was blue and empty. I pulled another can of beer out from under my sweatshirt and sat with my back to a column’s shaft. I wanted to go to Tropezedo — a club I’d read about in El Mercurio. Along the path that led out of the park, sodium lamps flashed on, popping and fuzzing into cold arcs. A figure moved between them with his head down. He seemed to be walking toward me, but without actually getting much closer or larger.

Watching him, I was furiously sad. We need separate, differentiated points, I realized, to understand the concept of space. The figure was of course you and the gap between us was only growing. No matter how hard you walked, you couldn’t get to me. In between the lights, the shadows completely overtook you.

My palm was damp, wrapped around the can. I looked down, adjusting my grip. But when I raised my head again, the figure was suddenly directly in front of me. He wore Levis and black high-tops and his hair was long. How could I have thought he was you?

He paused, shifting from foot to foot. His breath was heavy from the effort.

“You want something?” he said in English.

“These are Megaspores,” he grinned, uncapping his palm.

His fingers were smooth and his hands were big. Steam drifted from his body.

“No,” I laughed, embarrassed.

Untroubled, he repeated himself and smiled again. “These are Megaspores.”

He crouched over me and slipped his hand into mine so now I was holding the mushrooms too. We stayed like that under the monument, touching.

Now I was pacing, far from sleep. I pushed into my jeans and a windbreaker; it was humid out and it seemed like it might rain. I descended into the subway. There was a stilled train that felt like a mirage of the train I needed to catch. Lucky. I loped on. Inside, the G was bright and yellow. It dragged through its dark funicular caverns and at Lorimer, the L platform was for once empty.

It’s Friday night, I realized. I considered my options. The problem was, Terry was missing a case of top shelf. He thought I’d fenced it, used it at the BALLZDEEP party I occasionally threw. The accusation was lazy — easy to ignore. But the more I thought about the case I didn’t steal, the more I realized how easy it would be to take.

To my left, the tunnel gaped sourly, waiting to spit out the next train.

“Don’t you get it,” I’d said to Gerald. We were adrift in the horizonless midpoint of a happy hour east of A.

“Between what I might do and what I did do — there’s no difference at all!”

He stared at his brandy hand, planted thickly around his perpetual snifter.

“Have you ever eaten crêpes Suzette?” he said.

I knew by now that he’d cooked for Samuel, stubbornly brought him dishes at St. Vincent’s even when Samuel was intubated, practically gone.

I spilled out for another round. “Yeah, yeah.”

But he described the crêpes to me again in careful detail, so careful that even half-listening, I was sure I could smell them and taste them — the liqueury tangerine syrup, the brown crispness around the broken bubbles where the batter met the scorching, heavily buttered pan.

This train was taking forever.

“Yo,” interrupted a voice I recognized, sounding less like an art professor and more like an East Village court rat.

“Yo, B-boy. You sure about this Tamayo cat?”

I grabbed my gut. Was I sure about Tamayo? I mean, of course I should dig deeper, I had only just started to research.

“Shh!” I hissed into my windbreaker pouch.

But he was onstage now, looking for an audience.

My cheeks baked. It was my fault, I reasoned. Only I had stopped taking the pills — you were racing toward health. The more I thought about it the more it irked me. What was your rush? Let’s convalesce together, baby, I wanted to shout. Yoga retreats, long raw food dinners — once we had planned to go to meditation on Tuesday nights.

I should get my own life!

I stared at the subway map of Manhattan. It had always looked like the pro le of a big west-facing cock. Now a single beam glared out from the tunnel. I watched as it grew bigger and bigger to the point of engulfing me — then suddenly sliced into two.

I emerged through the mechanized subway door at First Avenue limp-legged. Under my windbreaker, my T-shirt was sweat-logged and I wrung the left corner of it until my fingers made prints in the cotton. The rest of me was wiry but no matter how many pull-ups I did my chest was soft. The wet fabric pooled there expectantly.

I slid through the turnstile cage with my head down. The message I’d sent you drifted in space without defense. I jammed my phone from my pocket, waiting for the signal to show.

It had rained while I’d been underground, and a tuberous smell came up from the pavement. I wiped my face, finally street-level. In this early-summer heat and quickly hosed sky, thousands of safety bulbs speckled the half-built condos: mutant-sized fireflies.

I no longer felt capable of being out. Shapes walked around in the dark with their shoulders bunched. I checked my phone again: blank. Mindlessly I logged onto YardHard as I moved. Rat574 ballooned up — he was perpetually “in the garden.”

Me: nice night.

Him: want to score?

I’d followed Megaspores toward what I guessed was Avenida Michoacán, trailing at a distance. Lebanese cypress lined the path, shooting upward, roughly rimmed by giant palm fronds. He walked briskly. I’d entered an alternate universe and was meeting an unknown version of myself who could have easily starred in Cruising.

Branches stretched over us like arms. Stuffed in my pocket, my left hand prickled where he’d held me. He walked faster, taking a staircase two at a time toward the corner of the park. His hips were narrow. Exposed, they’d be sharp. Yours are like that too and when you let me, I grabbed them as if you were a view scope and I was trying to stare inside. I imagined you back at the apartment moving around with purpose, turning the pages of a book or licking a joint.

At the top of the stairs, there was a small plaza. Megaspores stopped. We stood there, again very near. His long hair was oiled, glimmering in the light. Around us the atmosphere of the city buzzed and blared. I tipped the rest of my beer down my throat.

“Duck pond,” he said, pointing to our left. Helpless, my eyes followed. Where the concrete broke off, there was a low patch of water and, I supposed, a fountain. Then he grinned again and under the sodium lamp I could see the ’shroom caps hiding between his gums and teeth — he’d been chewing and chewing as we walked.

“Duck pond,” I repeated lamely.

Then I was mashing my lips against his open mouth, running my tongue everywhere. Duck pond, I thought again. His saliva was casting a kind of spell. Now my mouth was full of wet brown caps. Duck pond, my brain insisted. The substance was leathery, crumbly, and underneath, fecal, soft.

I shoved him against the cement base of the lamppost. He was my same height exactly. I felt his hips warm and springy on mine. But this had nothing to do with him! I was only finishing an act of balancing that he’d started when we asymmetrically touched. Meanwhile my cheeks had begun to fizz. I felt full of goop and light. I saw you at the balcony window waving. You and I hated each other sometimes but together we’d be fine.

“Tentigo.” Megaspores pointed, laughing.

I shrugged o my hard-on. So what? But I was becoming confused about which parts of me had touched him and which hadn’t. That morning in the shower you’d bent down wide for me to fuck you but I couldn’t relax and you’d turned off the water with your hair full of soap.

Now my upper lip was coated in sweat but when I ran my tongue along it the hairs were sour. He moved farther away. My brain was whirring. He must know Tropezedo, I thought. Light pooled around him in bright beams. My nipples pulsed where his chest had been. The distance was suddenly constant: unbearable. I closed the space with my arms but as if disconnected from my brain my hands crashed into his denim-covered ribs and crotch and then whacked at his chest.

“I’m hitting you,” I heard my voice saying.

I sounded hysterical.

“ESTOY fucking PERFORADO.”

He sidestepped me easily, dropping to the ground in a kind of squat thrust. Then he put his face down into the weeds. Beyond my panting I heard cars and sirens parading the boulevards. Blandly, as if he were at the clinic about to get a booster shot, he inched his jeans over his chonie-less ass.

“I’m Carlos,” he said, turning his misty head to me.

I passed through the Friday night party tents and teepees of the East Village in a hurry. This season everyone was tall and leafy. A girl with flaming hair smoked under the spastic yellow of Gray’s Papaya. Tilda again. She was like you. Safe from pain — emotionally no holes at all.

At the corner of C and Tenth, I bent over. All those pills in the dirt, now my bowels were involved. The leftover vegetarian gumbo I’d geniusly eaten for dinner slushed back and forth. I concentrated on squeezing my ass closed. Any port in a storm, I thought, whimpering my body through the fudge-colored door of the Baltic.

I stared around the familiar scape. Behind the long run of oak laminate, the cracked stools, the bartender’s skin emitted a neon sparkle. The new guy was just Terry’s type, as twinky as they come.

“Hey,” I said.

“Uh-huh.”

He swished his towel over a chalky spot I’d scrubbed a thousand times before.

“I need the staff bathroom,” I said. “I work for Terry. I run, you know . . .”

Wincing, I paused, giving him the chance to make something up.

“Uh-huh.”

“Give me the keys.” I stretched out my palm. “Right?”

“I should call Terry.”

Casually I rejoined a stray straw to its holder.

“You could,” I said. “In this shitty economy where no one trusts anyone, it’s one of those things you could do.”

I was yelling, the Baltic had become ear-splitting. Out near the dance floor and the wall gallery of second-rate reindeer heads, a karaoke machine blared. Someone was murdering Meatloaf. A guy with a bristly beard stood up on a chair and waved his arms. I would do anything for love! he shouted.

The bartender shrugged. His eyebrows said: I’m hot?

Fields of Japanese knotweed plowed through my brain. I caught myself in the long barroom mirror. My eyes looked like meatballs. I thought suddenly of RAT574. What a guy, he really cared . . . thick-chested, chest hair glistening, a warrior with Teutonic strength blasting our personal scourge from the face of Brooklyn eternal.

Would it really be so bad to have a clean yard? I saw us sitting there in it, drinking icy things. Weeds are like hair on the body of the earth, I said to myself. Not personal.

My pocket buzzed. I took a deep breath. One message. Slide, yes.

The text bubble popped. I squinted down.

Mexico??? you said.

I took the master key ring and made o into the annals of the bar with my heart wacking. Past the urinals, the pool table, the broken-off pay phone and its Sharpie forest. I had no idea what I was doing, only that Terry owed me my last check. I stood in the small liquor-barricaded office. Hundred-dollar scotches stared me down.

I wanted to know. Had you taken Terry’s side? When it came down to it? Or did you believe me?

It was dawn when I got to the Condesa apartment and the fruit vendors were unlocking their carts. I slid under the crisp sheet.

“How was Tropezedo?” you said, petting my abdomen. “Same old pinochas?”

I nodded.

But Tropezedo had been black and shiny, practically Scandinavian, packed with Carlos’s friends and bowls of metallic condoms sitting everywhere like grapes. Then there was Cockspot and a series of other bars with similar names. Over the course of the night my body had become big and dim and I floated in it like a visitor.

The next morning, we left for Oaxaca on a small seven-seater plane. I sat next to the pilot, a gaucho in polished aviators. As we skidded over the dark green hilltops, my hands crept under the backs of my heat-pancaked thighs. My head was in a tequila-made vise. With the copilot’s controls in front of me, I was sure I was about to wrench the plane down into the jungle floor.

Later, at the airport cafeteria, you were ebullient.

“Did you see it?”

My face was gray. “Giga,” I confessed, staring at your beautifully remote nail beds.

You grabbed my shoulders as if I was made of rocks.

“Earth to Leon,” you said, cradling my head, laughing. “We landed, we’re safe.”

A sick feeling spooled inside me. My vision turned to pixels and points. Our parasite rammed my sphincter. And my sphincter was just a weak wall! I could crawl to the bathroom but for what? For once I was exactly where I needed to be. Sweating, I unbuckled my belt and crouched down. Hanging my ass back past my heels, I squatted wider, my ankles pitching forward. This would disgust you. “Raunch factor ten,” you’d say. But what about Herrera, Bustamante, and No Grupo? Our parasite and I — we were careening toward a more conceptual kind of art.

I palmed the cash shelf for balance, breathing with yogic purity. The carpet smelled of large cat. Forget about order. I opened and a sheet of water and rice poured out, then I was sure I felt something tug free from my stomach lining and whoop down the chute. I stared between my legs — I felt suddenly better than I had in months. Out out! I chanted. In this zen state I could finally give as much as I wanted and more would come gushing down to fill the void always.

My phone rang.

I wiped with a discarded bar rag and quickly stood up.

“Hello?” RAT574 said. He sounded different than I’d expected, breathless and old, like he’d been sitting for too long with something in his hand.

I eased the office door closed and gave it a quick twist. The Baltic was blurry, more crowded. “Leon!” Gerald called from his appointed stool, but I barely recognized him. I threw the keys in the direction of the bar and ducked out into the cooling night, shoving the curtain out of my way.

At Fourteenth Street, a wad of guys with gym hats padded past plus all the regular queens but this time they must have been joking, their makeup caked thick and droopy.

I dropped down into the First Avenue subway.

Drunks plastered the lavender seats. A Poetry in Motion poem attacked my eyes, then an ad for Botox. Halfway through the tunnel I slammed a cartoon hand onto my forehead: you were in Chinatown at your brother’s, a plan you’d made weeks ago, probably under a roll-neck of Xbox and bong smoke.

It didn’t matter, I told myself. In Terry’s office I’d remembered my only rule. This rule trumped all others, which perfectly explained the crumpled shape of my life. As a kid I had another habit. Whenever something was too ruined, too bereft, or sick — say a saucer with no matching cup, a napkin mostly unused but with a splotchy stain, a baby mole tugged half-dead by a dog — I crushed it. More than anything I couldn’t stand to see suffering.

“Giga,” I said into your voice mail, as I stood on our corner of McGuinness and Nassau, waiting for who knows what.

I took a breath.

Then I confessed all kinds of things into the at receiver — disgusting attachments, lies blotting back as far as I could see, betrayal upon teetering betrayal — anything and everything that ran into my mind.