Books & Culture

A Stranger Could Very Well Be a Friend You Haven’t Yet Met

In her latest collection, Caldwell continues to bare all and relates to readers everywhere the conditions of living in our modern day

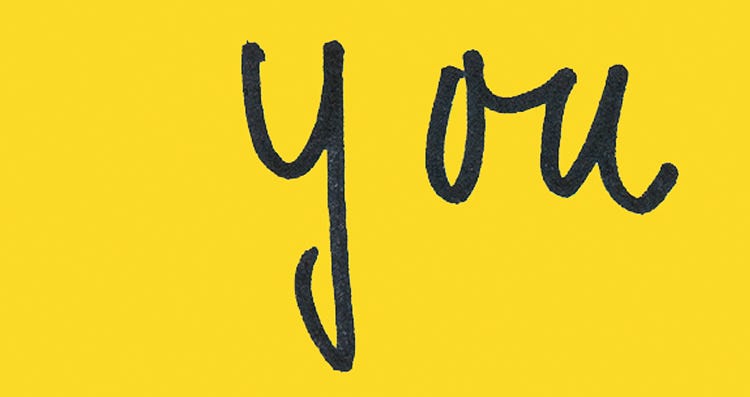

Because all strong personal essays strike a compelling balance between omission and disclosure, it seems fitting to begin this review of Chloe Caldwell’s exceptional personal essay collection, I’ll Tell You in Person, with the latter. Thus, full disclosure: I feel like I know Chloe Caldwell so well — about how she used to be a serious singer, about her parents’ divorce when she was in high school, about how she sometimes babysits Cheryl Strayed’s kids — that I am one of her oldest friends and therefore should not be allowed to write this piece of criticism due to a conflict of interest. How can one be impartial toward a person of whom one has such intimate knowledge?

But the truth is, I’ve never met Caldwell. I’ve never even read her previous books — the novella, Women, and the essay collection, Legs Get Led Astray — although after finishing this, her third, I intend to do so. I only recently began following her on Twitter — where to my delight, she followed me back — because I started reading this book and tweeted a photograph of the page on which she defines the concept of “participation mystique.” Writing about her own experience of getting hooked, at the age of 18, on the personal essay genre, Caldwell says of a piece by Miki Howald, which she found in a book on her older brother’s shelf:

But how did she do that? Take something from her life and craft it into this moving piece of art that resonated even though it had nothing to do with me? I inserted myself into the words and made her experience mine. I’ve learned this notion of not knowing where you end and the artist begins, while watching films and reading books, has a term: participation mystique. The concept is closely tied to projection.

So while it would be weird and untrue to say that I know Chloe Caldwell, after reading the 12 essays in this fantastic collection, I feel as though I know Chloe Caldwell, a statement which is a testament to the power and satisfaction to be found in her utterly funny, confiding, and self-aware skill as a writer.

Caldwell’s work shares similarities with other brilliant personal essayists. Sometimes she resembles the brainy, ebullient, under-achieving party-girl Eve Babitz, as in the piece “Prime Meats” which details her job as a jewelry shop employee in Manhattan as well as a zany-but-potentially-dangerous side hustle with her friend Ana meeting men through Craigslist to get steak and scotch. “Hey sexy bros,” their ad reads:

“Who wants to buy some prime bitches some prime meats and drink obscene amounts of liquor? Let’s kick it. P.S. We’re psycho (in a fun way) and we want to give you surveys.”

Other times, like in the essay “Failing Singing,” she resembles the self-interrogating, thoughtful, slightly neurotic approach of Meghan Daum in her wonderful collection, My Misspent Youth. “‘Singing changes your brain,’ TIME magazine says. ‘When you sing, musical vibrations move through you, altering your physical and emotional landscape.’ The articles about how good singing is for you almost hurt my feelings, as though they are written to make me personally feel bad,” writes Caldwell of her disappointment in herself at having given up her talent.

At still other times, she reminds the reader of the messy, heartfelt, and hilarious poignancy of Samantha Irby in her collection, Meaty. In “The Laziest Coming Out Story You’ve Ever Heard,” for instance, Caldwell uses eight deliberately shaggy, fragmentary, bullet-pointed pages to explore with great honesty and in vivid detail the “strife, grief, extreme distress” she sometimes feels in trying to come to terms with her sexual identity (or lack thereof) as a bisexual (probably) person who dislikes (but needs) labels. As she does so, she admits in a characteristically vulnerable and clear-headed way that:

I do not consider myself a political person. I never have been. A female author — I cannot remember who — once wrote something like, ‘I’m not political in my writing, why should I be? If you look at my life, I’m political in the way I live.’ It comforted me to no end. I do not watch the news. I read a little. I’m too sensitive for it and too dumb. But when I read that, I thought, Yeah! I don’t talk about women writers needing to be read, but I wrote a book that didn’t have any men in it without even noticing. Not tooting my own horn here, expressing my naïveté.

And that’s one of the traits that makes her book so much fun to be around, and what makes it stand out as free of many of the missteps that occur in even the best memoiristic and personal writing — Caldwell’s work is impressively devoid of horn-tooting. No humble-brags, no pity-parties. Just first-rate warts-and-all human complexity.

Not to mention that all favorable comparisons aside, I’ll Tell You in Person really does feel like an original and personal encounter with a singular individual, a conversation with an old friend you’re catching up with and don’t want to stop listening to.

In “Sisterless,” the piece about watching Cheryl Strayed’s kids, she includes a scene in which she and Strayed’s young daughter, Bobbi, are in “her mom’s library looking at the books on the shelves.” Caldwell points to one of her own books and Bobbi asks her what it’s about. When Caldwell says it’s about “My life,” Bobbi grows “uncharacteristically quiet. ‘Was your life sad?’ ‘No…’ I said. She perked back up and matter-of-factly said, ‘Good!’ ‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Because when people write about their life, they usually had a bad or sad life.’ ‘That’s a great observation,’ I said.” Nothing that terrible befalls Caldwell (thankfully) and she owns that many of the bad things that do arise are frequently of her own making.

Even though Caldwell examines big issues and experiences like falling in and out of love, getting and quitting jobs, and becoming addicted and un-addicted to everything from heroin to junk food, not all that much “happens” in these pieces, per se, and that’s not a problem. Her voice is so enchanting and engaging that it doesn’t matter. The book even acknowledges this relative plot-less-ness in one of its two epigraphs, the second one, from Patricia Hampl’s The Dark Art of Description, which says: “I get it. Nothin’s ever happened to you — and you write books about it.” Caldwell possesses such a masterful grasp of detail and tone that even the most banal anecdotes read like page-turners, and even the most dramatic incidents which could, in the hands of a less prudent writer, read as histrionic or self-involved, come across as sympathetic and in proportion.

Her inquiring mind, her sense of humor, and her personal responsibility make you want to listen to Caldwell all day and into the night. In “Maggie and Me: A Love Story” about her friendship with the late poet and writer Maggie Estep, Caldwell writes, “She’s had a unique and enviable past, and I want to hear everything about it.” Caldwell’s past is fascinating to that extent, too, and thanks to I’ll Tell You in Person, you can know everything about it — or at least she makes you feel like you can.