interviews

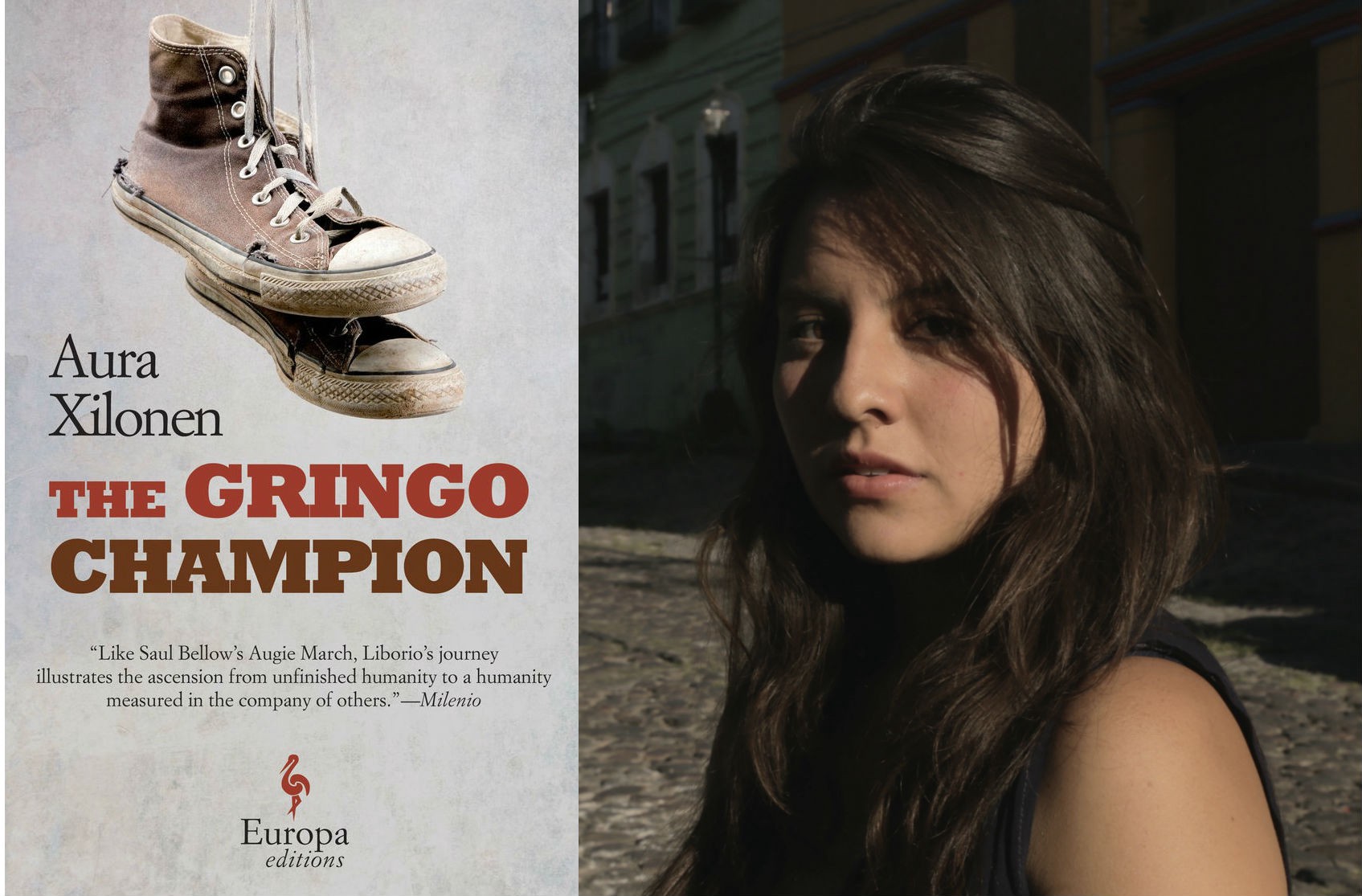

A Young Mexican Author Explores Life on Either Side of the Río Grande

Aura Xilonen on making the journey across the border, her own time as an undocumented immigrant and her debut novel.

Aura Xilonen wrote her debut novel The Gringo Champion (Campeón Gabacho) at age nineteen. The book tells the story of a young Mexican boy, Liborio, who crosses the border into the United States undocumented. Among anxiety-inducing episodes, violence, and an insane amount of swearing, the story follows Liborio as he scrambles to survive, gets a job at a bookstore and develops a love for literature — and boxing. The novel is funny, crude, experimental, and peppered with words that Liborio makes up as he discovers more and more language through reading.

Xilonen started working on The Gringo Champion at age sixteen, on the side of a job she still holds as a part-time cashier in her grandmother’s shop. She’s now finishing her film studies in Mexico. “Film is actually my first passion, and afterwards comes literature,” she told me. “Film is the love of my life and literature is discipline.”

Xilonen is generous, honest and oftentimes unmeasured. I first got in touch with her over email. She was casually affectionate from the beginning, in a way that feels immediately familiar, and which I rarely encounter in the English-speaking world. “Hi, cough, cough, cough. I was horribly ill with the flu last week. I spent all of yesterday in bed but I had to study for an exam at university. Cough,” she wrote in one of our first exchanges. In the exchanges that followed, she merged stories about life and family with more considered thoughts about the book and its reception at home and abroad.

The Gringo Champion, which won the prestigious Mauricio Achar award in Mexico in 2015, has been translated into eight languages. In English, the translation comes from Andrea Rosenberg, published by Europa Editions. The book has resonated in the Spanish speaking world in the last two years — Xilonen says she has received messages from readers telling her she made them laugh and cry in equal measure. In a recent review of the book appearing in The Los Angeles Times, Professor Ignacio M. Sánchez Prado wrote that “Americans of all stripes — including its intellectual elite — possess an astonishing level of ignorance regarding [Mexico].”

Let us hope that books like this one help breach that depressing divide.

Marta Bausells: You were a teenager when you wrote The Gringo Champion. Where did the idea for the novel come from?

Aura Xilonen: It came from feeling like I needed to preserve my memory. When I started writing it, my grandpa had just suffered a stroke, and I felt so much pain seeing him lie in a hospital bed, and later in a wheelchair. He used to be a giant, an oak. As far as I was concerned, he was made of the same matter stars are made of. Seeing him so diminished, slowly fading out, prompted me to write so I wouldn’t forget him. A lot of what Liborio goes through is based on stories he and my grandma told me about his life — he always would tell us of his adventures in Mexico and the US. It’s a shame he didn’t live to see my novel get published, though he would sometimes read parts of what I was writing about him and he would lift his hand and smile.

From a practical point of view, it came from the fact that when I was a kid, I lived in Germany for two years with my aunt, and she forced me to write 1,000 word-long letters that we religiously emailed to my family in Mexico. This was incredibly hard initially, but as years went by, I guess this weekly practice trained me, perhaps a bit like athletes train for the Olympics.

I also think my novel is an homage to my ancestors. My grandparents are the roots, my uncles and aunts and mother are the branches, my brother and cousins the fruits, and I am a tiny flower, shyly hiding between the leaves and the birds.

Bausells: The story revolves around the experience of an undocumented immigrant and the struggles he encounters, and a lot of it is set in the underground boxing world. What kind of research did you have to do to immerse yourself in that world?

Xilonen: It didn’t involve much research beyond some internet searches about boxing teams and brands. Like I said, most of it is based on the stories my grandfather, also named Liborio, told me, and some is based on my own experience living in Germany as an undocumented immigrant, the fear of being discovered in my aunt’s apartment, or the anxiety of going to school and not understanding anything, because my schoolmates were Turkish, Arab, Chinese or Japanese. We played and talked using sign language.

All my characters are a mix of myself and people I know, especially my family. For instance, the character of the Chef is based on my uncle who challenged me to the impossible mission of reading the entire dictionary, because “we’re language” and “our ideas are as long or as short as our vocabulary is,” he would say. I actually used a male character because he told me that if I wanted to grow with my stories I had to use a man, and see what I would come up with. It was like a literary exercise and I liked the idea of it.

Bausells: I found the contrasts in the book interesting: between violence (physical and in the language) and love (with often sickly-sweet, over-the-top, uncontainable language); or between the street and the sanctuary of sorts that is the bookshop. How and why did you decide to introduce these discordant elements?

Xilonen: Maybe because love is also a form of violence: the stolen, annihilated or resuscitated kisses; the hugs that asphyxiate; the caresses that feel like hammers … Maybe the best-tasting kisses are those after a fight.

I think most people aren’t romantic in their daily life, and that explains why we make books that taste like honey. I’ve always been shy and quiet, maybe because as a kid I moved schools and had to change friendships constantly. I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere and I hated lots of things, including dancing, avocado, and anything jelly-like. I still do. But I’ve discovered that, through writing, one can find a hidden romantic side that doesn’t usually come out.

Bausells: The novel is also a true love letter to bookshops.

Xilonen: Yes. At home we had a library of over a thousand books and it used to be my brother’s and my refuge when my mom told us off. It was the one place we could just be, away from the shouting. Also, my grandfather always read a lot. My memories are of him with an open book. His bed and study were always full of scattered books.

Planes Flying over a Monster: The Writing Life in Mexico City

Bausells: This has been the first time I have read a full Spanish novel in translation, being a Spanish speaker. It was weird and fascinating, and I spent half the time checking the original text to compare, especially as you use so many popular and made-up words. I loved Rosenberg’s work (with countless hilarious words like “wordify” or “knockoutified”). But this is a book full of Spanglish and full of culturally-sensitive nuance, starting with its title. What was the translation process like for you? Were you worried its essence might get lost?

Xilonen: On the contrary, I love the final result. The intention was for the language to be reinvented in each of the languages. I bow in front of Andrea Rosenberg’s extraordinary work. I created those words to signify that, as Liborio starts to read, his lexicon is very poor, but as he learns and reads the dictionary, he starts naming things with his own words … And I prefer the term Ingleñol to Spanglish, because in the original novel most of it is in Spanish — and it gives me more pleasure to use the Ñ that English doesn’t have and which Cervantes’s language contributed to the world.

Bausells: Liborio suffers all kinds of violence, is beaten up and chased several times, has a miserable past, and is running away the whole time. Was that a conscious decision you took?

Xilonen: The world has enough violence; it’s exacerbated by the media and the internet — and what’s even more tragic, by us through social media. And, even if my intention was to put Liborio in situations of physical and emotional violence, at the same time there’s hope, love and solidarity alongside the anger and the hate. In fact, in the most chaotic and vulnerable situations in the book, somebody lends him a hand. There’s always hope, at an arm’s length — as long as we don’t eat each other.

“There’s always hope, at an arm’s length — as long as we don’t eat each other.”

Bausells: Which other authors have influenced you, and what did you read growing up?

Xilonen: Much like Liborio, I started by reading books that had drawings, illustrations, like Asterix and Mafalda. Then I moved on to children’s books. Harry Potter was one of the watersheds of my life — I wouldn’t leave my room until I finished those mammoth books. Later, I read all the trilogies my girlfriends were also reading: from Twilight to Hunger Games — or, later, Fifty Shades of Grey. At the same time I was reading Tolstoy and Tolkien.

The author that most dazzled me was Juan Rulfo — everyone told me his Pedro Páramo was a masterpiece of universal literature, but the first time I read it, it was incomprehensible to me. The second time I started to get it. The third time I was mesmerized by his use of words, how they bounced along the edges of the page. Right now I read everything, especially theater, because I am studying cinematography, so I am reading everything from Shakespeare to Ibsen.

Bausells: The book describes the horror of crossing the Río Grande and everything that comes after for migrants. Were you trying to transmit a political message about immigration and humanity?

Xilonen: All human creation has a political message, some more untarnished than others. I wasn’t thinking about politics when I wrote this work, but I also didn’t want to disentangle myself from that relationship. I was mostly focused on the story, but I also thought about the dearth of the desert, the border and the storms they could trigger in Liborio’s life. I thought about the tragedy and suffering of my character and then extrapolated it to the millions of sufferings that must exist out there; about their forgotten screams. I thought about the thousands of anonymous graves that must store the bones of disappeared migrants. I thought about the stories of some of my grandma’s workers who had gone away as mojados (name given to Mexicans who enter the United States by crossing the Río Grande– literally meaning “wet”) and on their returns talked about the hell they had lived in the States.

“I thought about the thousands of anonymous graves that must store the bones of disappeared migrants.”

Bausells: What’s your life like in Mexico?

Xilonen: I live in my grandmother’s house with my mother and my uncle and aunt. We have a goose, some hens, a chihuaua named Musa, and two Australian parakeets that kiss each other from time to time. I live close to a big lagoon, in Puebla, and when it’s hot there are mosquitos everywhere. They fall on our skin like bombardments. Whereas when it’s cold, our house is a freezer and we often see penguins coming and going. My grandpa was cremated and he rests in an altar my grandma got built in the corner of the living room, and there rest his picture, his glasses and his fountain pens. And I think everyone in this house is slightly mad.

Bausells: What do you make of people calling you a “prodigy” or the like? And, if I may be a bit impertinent myself, how did you manage to get published before you were 20?

Xilonen: On the contrary, I feel like I’m already elderly, because life moves too fast and if you don’t do everything you must do at the right time, opportunities go by in the blink of an eye. We have young prodigies like Mozart, who composed his first work at four, or Rimbaud, who wrote his masterpieces at nineteen and then stopped, or Mary Shelley, who wrote Frankenstein at seventeen. There are many examples. I only learned to write because they forced me to. It was as if I were doing military training — that’s why I compare it to sports. Before I started this book, I’d been writing for nine or ten years.

Bausells: What have you learnt since you wrote The Gringo Champion?

Xilonen: I have learnt not to be scared, because people see me differently now — especially at university, they think a writer knows everything. But no. I’m twenty-one and I have thousands of movies to see and millions of pages to read. Gah!

Bausells: One of the accomplishments of the book is how it generates empathy. Being that the story is set in a border town in the US, featuring an “illegal immigrant,” it was painful and apt to read it in January, as Trump took power. Was that on your mind these last few weeks?

Xilonen: Unfortunately you’re right. I would have loved for the book to be just fiction, but now, it looks like we might be talking about a terribly hostile and damaging time for all of us in which tolerance will become, again, a dream to fight for, when it felt like we were starting to have it at an arm’s reach. But there’s always hope — in the same way that Liborio finds helpful allies so he doesn’t fall into the abyss, I think most Americans are wonderful, tolerant people, open to humanism, generous and committed to freedoms, dreams, and helping those in need, those most unprotected.

And I also believe that most Trump voters made that choice because they couldn’t find an exit to their dissatisfaction and desperation, and that they’re people who wouldn’t attack another human being. I believe that they wouldn’t humiliate another person for their color, culture or religion. We must worry about those who fly the flag of racism and use hatred as their weapon to harm others, because they still haven’t understood that the world is so diverse, and that that’s where all its beauty stems from. And if my book can make a small contribution to living in better harmony, I hope it does so.