Books & Culture

Actually, Other People’s Dreams Are Cool

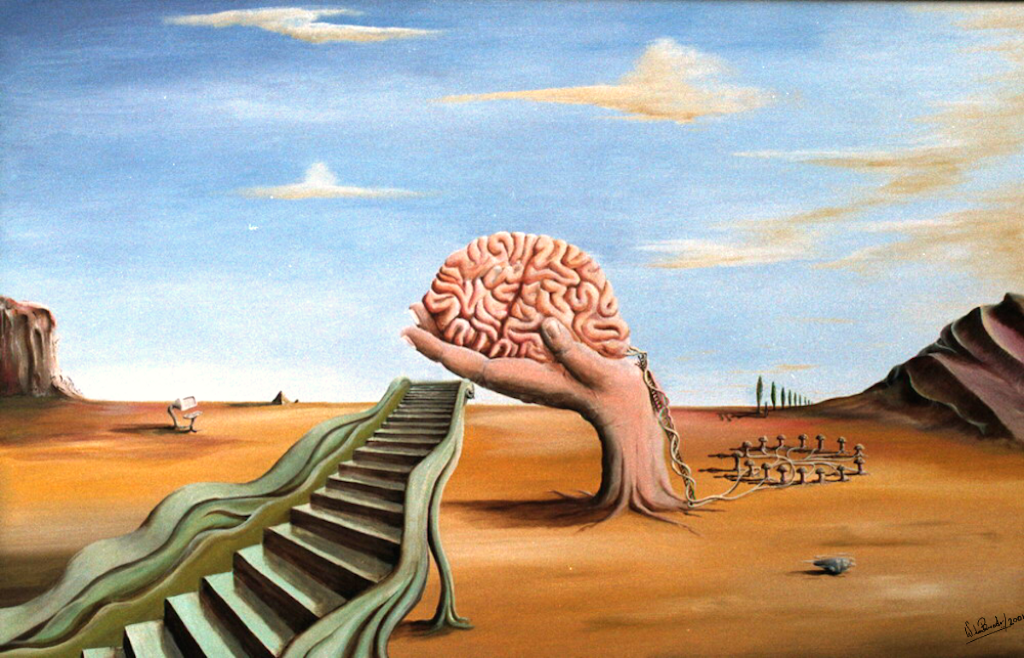

How to Build a Dream World Creators like Kelly Link and David Lynch use “night-time logic” to make fantasies feel significant

One of my earliest memories is of a nightmare. In it, I’m on a train traveling across a wide desert expanse under a big, cloudless sky. This train car is almost entirely empty, and I’m alone, staring out the window at the sunny cliffs in the distance, their golden-brown faces regal in the light. Amidst all the beauty, a giant, winged demon emerges. It swoops across the open plain and flies past my window, its gaping maw emitting a piercing scream before it disappears. In fright, I bend over and vomit up undigested peas and carrots; then I wake up.

What strikes me most about the nightmare in retrospect is not the demon but the desert landscape. I must’ve been five or six when I had this dream: young enough that I remember waking up in my childhood bed, screaming for my mother, and far too young as a resident of suburban Northern Virginia to know what the desert looks like or to have ever traveled by train. And so I’m left to wonder: where did my brain find these images? Had I, while waiting in a doctor’s office, seen a picture of the desert or a Georgia O’Keefe painting? Did I start watching Tales from the Crypt as a small child? I find this hard to believe, given that my television viewing at age five was limited pretty exclusively to Little Bear and The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh. And yet somehow my brain managed to transport me to a landscape that, to this day, I have never actually visited.

My lifelong fascination with dreams began there, in the mystery of that desert, and has continued since then, spilling over into my waking and writing lives. This fascination is not truly analytical in nature, though I have turned on rare occasions to Freud and dream interpretation manuals. (Did you know that being bitten by an alligator in a dream symbolizes treachery on the part of a loved one, particularly a family member?) Mostly, it manifests itself in a small dream journal, in which I occasionally remember to record the more vivid dreams and nightmares my brain conjures. I rarely share my dreams, for fear that I will become That Person at the party, but I’m always interested in hearing about other people’s dreams. Recently, I picked up Insomniac Dreams: Experiments with Time by Vladimir Nabokov, edited by Gennady Barabtarlo, and was enthralled by the rich depth of imagery in his dreams, as well as in his wife’s. In one, she dreams of a granite hotel where the staff rings a bell every time a large white caterpillar crawls over the furniture. In another, he comes across a box of butterflies and only after trying to squeeze the last living butterfly to death realizes that there’s a man sitting next to him, preparing a slide for a microscope. This delayed awareness of the other’s presence is common in Nabokov’s dreams, as in his fiction. In Lolita, narrator Humbert Humbert describes a dream in which he’s riding horses with the title character and her mother, only to discover there is no horse underneath his bowed legs — “one of those little omissions due to the absentmindedness of the dream agent.”

I rarely share my dreams, for fear that I will become That Person at the party, but I’m always interested in hearing about other people’s dreams.

This “dream agent” is Humbert’s invention, the subconscious factor he imagines controls his sleeping visions. That’s one way to explain the features of dreams that are out of step with the real world, the appearances and disappearances and strange juxtapositions. Another is night-time logic.

“Night-time logic” is a term attributed to author Howard Waldrop, who distinguishes between the daytime logic that governs the waking or “real” world and the more fantastical—but no less internally consistent—night-time logic that governs his writing. Waldrop is a big figure in the world of speculative literature, and he won the Nebula Award and World Fantasy Award for his novelette “The Ugly Chickens,” first published in 1980 in Universe 10. In the story, Paul Linberl, a graduate student in ornithology at the University of Texas, meets a woman who claims that her family raised dodo birds in Northern Mississippi in the 1920s. Paul naturally finds this fascinating and impossible and embarks on a wild dodo chase in search of the extinct bird. While in pursuit of the dodo, he relates a vision he used to have before he struck out on this quest. In his vision, he’s in the Hague; the Dutch royal family is eating dinner; and, as Pachelbel’s Canon in D plays in the background, four dodos enter the dance floor, their awkward bodies suddenly graceful as they move and sway. Reading this, I cannot help but recall the dwarf from Twin Peaks: how he dances stutteringly in the red room of Dale Cooper’s dream (which, he later learns, he shared with Laura Palmer, who dreamed of the red room the night before she was murdered). Like the dodo birds dancing in the Hague, the dwarf is part of a premonitory vision — a moment in which both Paul Linberl and Dale Cooper are offered a window into the future, only to forget or misinterpret that vision upon their return to the waking world.

In order to reconstruct the insight he had in his dream, Cooper has to first understand the night-time logic that underpins it. That means unlocking a series of clues. When Laura says, in the dream, “Sometimes my arms bend back,” she’s referring to the way her arms are bound with twine. And when the dwarf says, “That gum you like is going to come back in style,” he’s referring to the gum that the aged waiter hands to Leland Palmer seconds before Cooper solves Laura’s murder. This is night-time logic at work: seeming non sequiturs existing in a world where they’re not only accepted but later proven essential to the functioning of the world itself.

This is night-time logic at work: seeming non sequiturs existing in a world where they’re not only accepted but later proven essential to the functioning of the world itself.

When I first watched the original series of Twin Peaks, I was in college and did not yet know the term night-time logic. That came later, while studying the works of Kelly Link. I was introduced to Link’s work in graduate school, in a science fiction workshop led by Kevin Brockmeier at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. We read “Catskin” from Magic for Beginners, the first book of Link’s I read. Like Cooper’s visions in Twin Peaks, much of Kelly Link’s work operates on the level of night-time logic. In stories like “The Faery Handbag” and “The Hortlak,” she introduces readers to worlds where entire villages can be found Mary Poppins-style inside an old woman’s handbag and where zombies drift in and out of convenience stores, never bothering to attack the cashiers. It’s a testament to Link’s skill as a writer that readers never once question the central conceits of her stories. She does this through deft and deceptively simple world building. Take this passage from “The Hortlak” for example:

The zombies came in, and he was polite to them, and failed to understand what they wanted, and sometimes real people came in and bought candy or cigarettes or beer. The zombies were never around when the real people were around, and Charley never showed up when the zombies were there.

At first glance, the passage seems merely utilitarian: the narrator describes a typical night at All-Night Convenience, where the main character, Eric, works as a cashier. In reality, Link is using a moment of exposition to establish some of the fundamental rules of the story: 1) Not everyone in this world is a zombie, 2) the zombies are not particularly violent or interested in brains, 3) other than Eric, humans are never in the All-Night Convenience with the zombies, 4) Charley is never there when the zombies are there, ergo 5) Charley is not a zombie. By presenting these otherwise strange rules as part of the fabric of Eric’s everyday life, Link makes it possible for the reader to suspend disbelief and accept the story on its own terms, according to its own logic.

When considering the works of Kelly Link and David Lynch in tandem, it becomes clear that the artists are employing night-time logic to two distinct but not entirely dissimilar ends. For Lynch, night-time logic is a tool that he uses to chip away at daytime logic — that is, at the surface image of perfection and normalcy that Twin Peaks the town likes to project. Through a combination of excellent detective work and unusual deductive techniques, Dale Cooper discovers the darkness, madness, and depravity lurking underneath that illusion of perfection, thus uncovering the truth. One could argue that this is the larger goal of Lynch’s oeuvre: to undercut that normalcy, to take the perfect little towns of Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet’s Lumberton and reveal their underbellies. Kelly Link, on the other hand, does not assume normalcy as a baseline, but rather uses night-time logic to establish a new normal: another fantastical world wherein the characters we meet and the events that take place reflect back on our reality, thus teaching us something about what it means to be human. Ultimately, both artists are interested in exploring the subterranean desires that live under the surface of our daily lives, but the mediums through which they do this and the manner in which they explore those desires prove different. For David Lynch fans looking for a way into Kelly Link’s work, I suggest “Pretty Monsters.” For Kelly Link fans interested in David Lynch, I suggest Mulholland Drive.

Studying night-time logic has not alleviated my night terrors (on the contrary, the 2017 revival of Twin Peaks inspired some of my most vivid and symbolic dreams to date), but it has changed the way I think about nightmares in my waking life. Instead of viewing them as visceral experiences of terror or revulsion, I instead think of them as opportunities: narrative filters, like Link’s stories and Lynch’s films, through which I am able to examine the world around me, as well as the inner workings of my own subconscious mind. Like Nabokov with his dream records, I write down my nightmares not to emphasize their power but to understand the linkages between the dream world and the real world and, from there, enhance my own creative practice. This act has opened me up to a wealth of narrative possibilities and coping mechanisms that simply were not available to me as a little girl dreaming of demons. Back then, I felt alone in my terror. Now, as an adult, I know that dreams are not just the bewildering byproducts of our subconscious minds. They are fuel for art.