Books & Culture

Adolescent Obsession and Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick

The cult novel’s adaptation as an almost-there Amazon television pilot

Our dance teacher was an ideal object of adolescent obsession for my best friend and I. We were fifteen and he was forty. A young, disheveled, oblivious forty, a working-class Michigan sports fan whom we never saw without a baseball cap on. He was bisexual and unmarried, chain-smoked cigarettes and argued with us as if we were equals. If we weren’t trying hard enough or he was simply in a bad mood, he would make us do punitive drills. “It’s too hot,” we’d say. “Hot is better than cold for your muscles times infinity,” he’d answer. He was the most exquisite dancer any of us had ever seen. Even the unobsessed were overcome by his dancing when it happened, which was rarely.

After each class my friend and I would sit in the backseat of my mom’s car and dissect every moment. What he wore, what sort of mood he’d been in, had he made eye contact with us, for how long? If he’d come around to readjust our bodies, what had his hands felt like, how many seconds did he touch us, did he touch me longer than her, what did that mean? “His hand was here.” We would touch each other. “From now till” — counting the seconds in our heads — “now.” Before we knew his age, we had spent hours hypothesizing. He might look older than he was because he smoked. He might look younger because he was an athlete. Or maybe he was ageless. We made him mythological — he never took his hat off; he showered in it; his head was shaped like a baseball cap; the hat we thought he wore was, indeed, his head.

This obsession, of course, had very little to do with our teacher and everything to do with my friend and me. He happened to be the perfect vehicle for our energy — he was unusual, solitary, and, most importantly, safe. But perhaps anyone would have done. Our focus was internally on each other, on this obsession we worked on together, this project. We fed off the other’s mania. If she hadn’t loved him too, I would not have loved him as much. We squirreled away each memory, gathered content for later, for when we would be alone together to continue our work. Sometimes we didn’t even hear him talking, because we’d been talking to each other about him.

It is this very specific category of obsession, that when I recognized it in the first few pages of I Love Dick triggered an exhilaration I haven’t felt since I was fifteen — the memory of a closeness I haven’t had with anyone else since my friend. At the beginning of the book Chris Kraus writes about the protagonist, Chris Kraus, and her husband, Sylvère, spiraling absurdly, terrifyingly, and very recognizably out of control. They take turns writing letters to Sylvère’s colleague, Dick, with whom they have had one dinner and a somewhat intimate overnight stay at his house because of bad weather.

At that dinner Chris unexpectedly “notices Dick making continual eye contact with her,” and finds herself a bit stirred, alerted to him. One page later, at Dick’s house, while the three are drinking, Chris sees that Dick is openly flirting with her. The couple watch a video of him dressed as Johnny Cash, and Chris’s complex reaction to his bad art strengthens her connection to him: “She dreams about him all night long. But when Chris and Sylvère wake up on the sofa bed the next morning, Dick is gone.”

Chris and Sylvère leave Dick’s house without seeing him again. “Because they are no longer having sex, the two maintain their intimacy via deconstruction: i.e., they tell each other everything. Chris tells Sylvère how she believes that she and Dick have just experienced a Conceptual Fuck. His disappearance in the morning clinches it…” With that, on page three, we’re off. We don’t really need Dick anymore. We are swept into Chris and Sylvère’s universe, where they wind each other up, pass the laptop back and forth, in bed for days, writing letters to Dick concerning Chris’s infatuation with him.

We as readers find ourselves wondering — less from the way this book is training us to think and more because of how the common conflicts in our lives have trained us — about jealousy. And indeed, Kraus writes, “Why does Sylvère entertain this?” Some reasons are offered: because he loves Chris and she is suddenly alive, because he himself is bored, avoiding other work, enjoying the collaboration. But, I would argue, these don’t fully encompass the hysteria which Sylvère participates in. In his own letters to Dick he wonders what they’re doing and about his role in it, trying to fit the phenomenon into a recognizable situation — “a ménage à trois” — and he himself into the stereotype of “the willing husband,” though none of it is right. The hysteria he shares with Chris is its own intellectual and emotional project, one separate from Dick. “They take turns giving DICK-tation. Everything is hilarious, power radiates from their mouths and fingertips and the world stands still.” The hysteria is Sylvère’s as much as Chris’s. And without his participation, without having him to share it with, I wonder whether Chris’s infatuation would reach the heights it ultimately reaches.

This shared experience between Chris and Sylvère is what’s missing in the adapted Amazon television pilot episode of “I Love Dick.” It’s been replaced by other elements that will perhaps be more successful across a full series — a new character, Devon (Roberta Colindrez), a neighbor of Chris and Sylvère’s, seems especially promising. But this shared hysteria is such a singular and powerful element in the book that it was what I had been most excited to see interpreted. And maybe it will be in the series’ subsequent episodes (the pilot — helmed by “Transparent” showrunner Jill Soloway — ultimately got picked up. This is only the beginning).

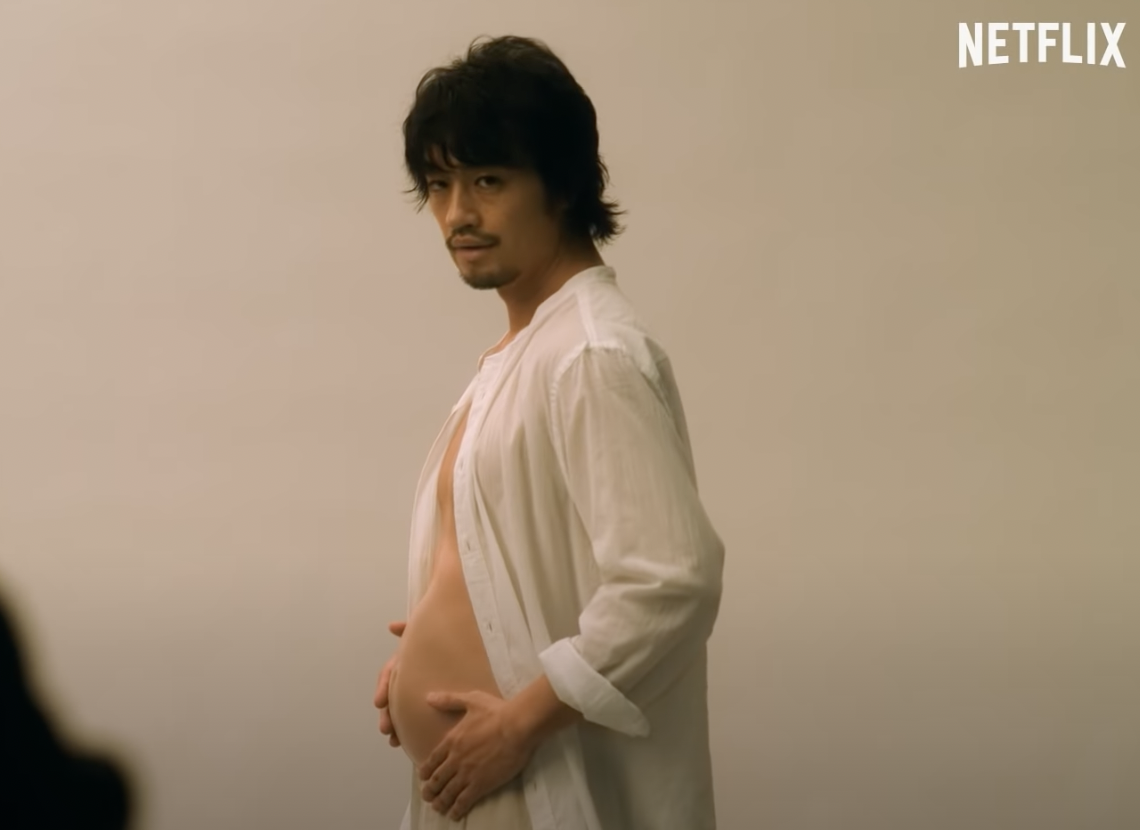

Even if they portray it, the subtle but substantial differences in Sylvère’s character (Griffin Dunne) make me think that the hysteria will have a different tone. In “I Love Dick,” Chris (Kathryn Hahn) and Sylvère’s dry spell is far more highlighted, and a source of passive aggression between the two — a dynamic not particularly significant to the book. Sylvère demands that Chris read him the story she wrote about Dick after they have dinner with him. In hearing about her desire for someone else, he is aroused for the first time in a long time, and ends their dry spell in a brief, triumphant burst. In the book it seems that the intense intimacy of writing letters together ends their dry spell, more of a natural, mutual — if unceremonious — progression of emotions. The sex is mentioned only after thirty pages — “and then they made love” — but not described, which lends to a sense of fluidity in all their modes of intimacy: writing, talking, taking turns to make coffee, having sex, describing their dreams, juggling finances, and living all over each other.

Dick in the pilot, too, differs from his text-based counterpart. He’s much more prominent in the show, and I suspect will continue to be. For one thing, he is played by Kevin Bacon, a perfect choice for the portrayal of the inaccessible cowboy. We also have scenes of him alone, signaling that he’ll perhaps be a character in his own right, and not one seen solely through Chris’s lens. In fact, so far he has been a much more active participant in instigating a situation with Chris. Dick on screen is shown to be visibly annoyed and disappointed when Chris mentions that she has a husband. At dinner he is provocatively insulting to her both as an artist and a person. And he’s aggressive, challenging her in a way that does indeed seem sexual. In the book, on the other hand, Chris’s idea that Dick has proposed some sort of game between them seems very much in her mind, an extension of her increasing infatuation, though Dick himself remains oblivious and uninvolved, no longer physically present at this stage. For Dick in the show it seems the game may very well be something real between him and Chris, something which doesn’t involve Sylvère.

Near the end of the episode, Chris and Sylvère’s neighbor Devon decides to write a play about the pair after observing them, describing the idea to friends as centering on “a couple from New York. It’s not about a couple; it’s about a woman. And she hates herself. And her husband, he kind of hates her too. And the play is about them figuring that out.” It seems that Devon is poised to be our interpreter in the series, which should come as a reassurance: calm, reasonable, and constitutionally the opposite of the other players in the drama, there’s no character I would rather have in that role.

I believe that this, Devon’s description, is what the show will ultimately be about. But it’s not how I would describe the book. The way Chris feels about herself and Kraus’s embedded ideas about Jewish 1990s art-world feminism — ideas that become expansive through their specificity in the book — are complicated. Perhaps topics better left for a separate discussion. As far as Sylvère is concerned, I did not read him as hating Chris, the way he loves her in some instances even bordering on the divine. He is committed to her well-being; he loves her separately from their togetherness.

These relationships as they’re shown in the pilot, between Chris and Sylvère, Chris and Dick, feel more common and categorizable than they do in the book. The conflicts are easier, more in the realm of situations we’ve seen before. And, in the book, Kraus eventually reaches beyond the hysteria between Chris and Sylvère, towards a simpler, perhaps more adult form of obsession. In her afterword, Joan Hawkins writes that the novel “establishes a fictional territory where adolescent obsession and middle-aged perversity overlap and intersect…” We see that as Chris goes on alone to write to Dick for many, many months. And maybe that’s the point: this particular kind of intimacy, this intense creation and cocooning that Chris and Sylvère engage in together is not sustainable. It’s rare, and — should it happen at all — it is fleeting. Maybe that’s why I haven’t experienced it in my life again since I was fifteen. Maybe I’m lucky to have experienced it at all.

In trying to describe the phenomenon I experienced with my friend — akin to that happening between Chris and Sylvère in the book — I’m perhaps doing something more similar to the Amazon pilot. I’m spending much more time describing our dance teacher — our Dick — than looking directly at an intimacy so intense that it transcended jealousy. That intimacy is much harder to study, harder to describe, because my friend and I weren’t opposite each other, staring at one another. We were side by side. We were completely together and staring out at the world.