interviews

A Cult to Reform Bad White Men

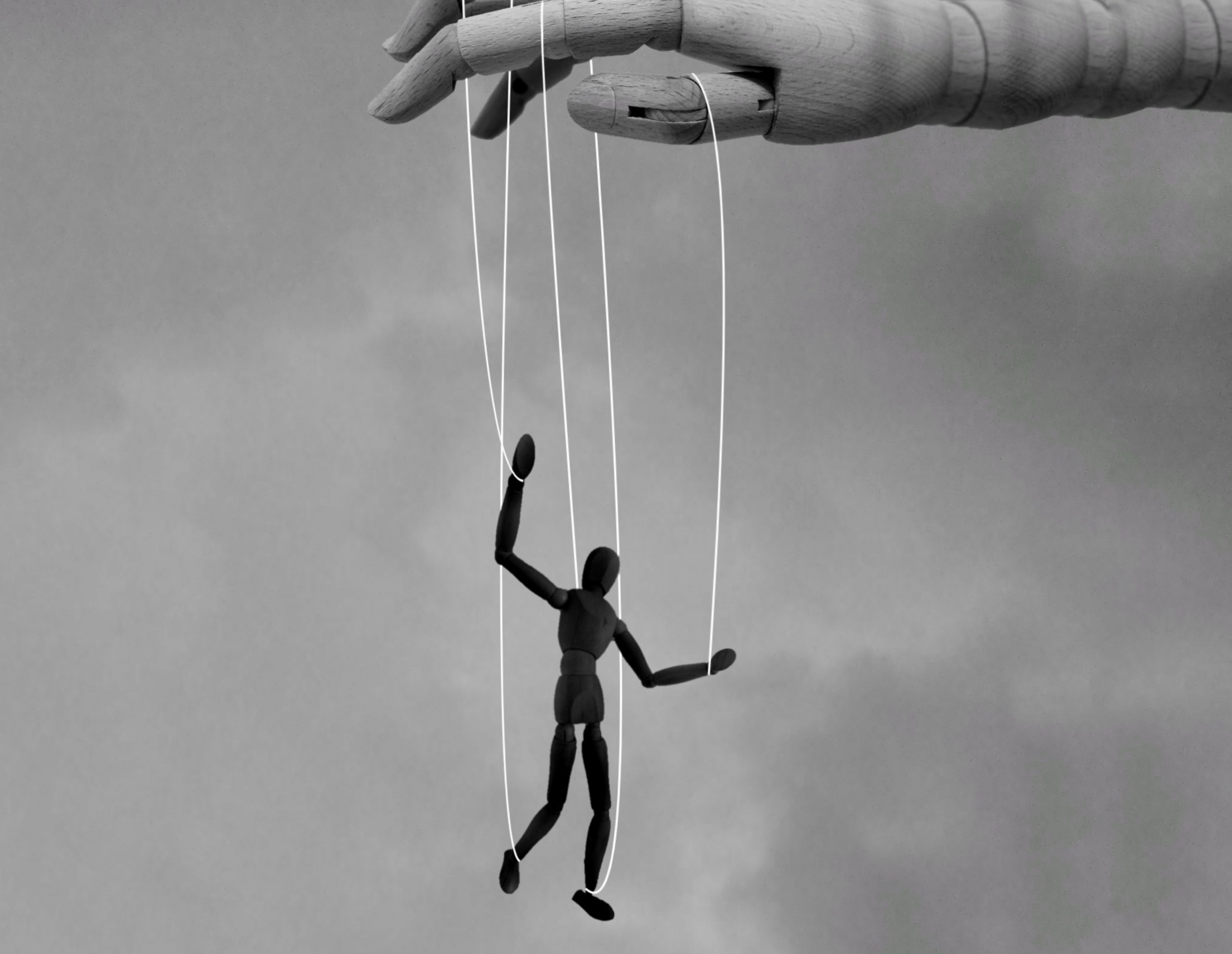

Alex McElroy's satirical novel "The Atmospherians" is about a disgraced influencer trying to cure toxic masculinity

“Man hordes [:] a blessing or a curse? Tonight we hold a debate.”

All over the United States, men (“always white men”) are hoarding together to perform unprompted, unpredictable tasks. Afterwards, they have no recollection of joining the horde; a perfect black hole where their actions lived.

- A man horde in Columbus, Ohio, rescued a ten-year-old girl’s kitten from a very tall tree.

- A man horde mowed twenty-six lawns in Drain, Illinois.

- A man horde in Plano, Texas, kicked a German Shepherd to death.

According to the CDC, men are three times as likely to horde if they’ve horded before—and it’s into this dark, satirical context that Alex McElroy’s debut novel unfolds.

The Atmospherians follows the story of Sasha, a disgraced wellness influencer, and her childhood friend Dyson, who wants to start a cult to reform men. Here, the men (or Atmospherians) will become the equivalent of film extras: “people who provide the atmosphere and stand in the background. What better aspiration for men? To… let the action continue without them.” By joining the cult as its co-founder, Sasha finds an escape from a life that has closed in around her; but she is also finds herself on several acres of inhospitable land with thirteen men.

In turns funny and grim—but always verging on the terribly real—McElroy’s skillful debut takes readers deep into the strange zeitgeist of wellness, internet culture, and the many faces of masculinity that often seem to coalesce into one. As one of the questions in Dyson’s survey to the potential Atmospherians reads:

It’s so hard for men in this world.

☐ True.

☐ Very True.

In many ways, McElroy’s novel is perhaps the story of a world (our…world?) in which the choices before us can feel bizarrely skewed.

Richa Kaul Padte: As teenagers, Sasha invites Dyson into “a world of self-doubt and surveillance”—diet culture, body policing, toning, shaping, the list is endless. She reflects: “For him, this was a vacation. Once he shed the weight, he would return home to the safe shores of masculinity, abandoning me.” I know this is sort of a central question of your book, but just briefly: how safe are those shores?

Alex McElroy: This is such a great point—and it highlights one of the main conflicts of the book. In this passage, Sasha is speaking out of resentment and an awareness of Dyson’s male privilege. Yes, life will likely easier for Dyson because of the gendered inequalities built into a patriarchal society. However, when Sasha fails to see the ways that Dyson’s conditioning harms him and makes him vulnerable, she loses touch with her own humanity. The shores of masculinity might be safer than what Sasha experiences every day, but that doesn’t make them unimpeachably safe for the people who live there. And the book asks Sasha to reckon with this reality.

RKP: At the heart of The Atmospherians is not just the performance of identity, but a feeling that this performance is what gives characters a sense of self—for Sasha, this has mainly happened online; for Dyson, offline. But over time, the more stable their performances grow, the more their selves seem to fracture under the weight. Is our compulsion to be singular selves without contradictions largely down to the internet pushing us to stay “on-brand”, or is there also an offline drive to fashion ourselves into consistent entities?

AM: Consistency is a privileged position—like, imagine if the world is so built for you that you never need to adjust who you are? Which is to say, I don’t think that it’s the internet pushing us to stay on-brand. I think that the notion of remaining on-brand has been, for generations, a fairly problematic demand imposed on marginalized people—and weaponized against them when they do not remain consistent. It is normal to code switch, to be inconsistent, to contain many selves. Think Whitman and his multitudes. That said, the desire to be consistent and singular is normal insofar as its normal to wish you could avoid the realities of being human: we’re inconsistent, we contradict ourselves, we shape-shift as a means of protection.

RKP: There are files on each of the Atmospherians, but one stands out—an outlier named Peter who “Dyson described…as ‘already a very good man’. There were no redder flags.” I think many of us have arrived at this realization in different ways, but: what is UP with the so-called “nice guys”? What makes them the reddest flags of all?

Consistency is a privileged position—like, imagine if the world is so built for you that you never need to adjust who you are?

AM: Sasha has been burned by men who called themselves nice guys, and now she’s suspicious of the label. The movie Promising Young Woman—and apologies to my friends who hated it—does a good job of interrogating the nice guy brand, delving into what might lurk beneath that superficial label. To speak more generally, over the last couple years, I’ve learned that when you think you’re an expert in something you tend to set yourself up for a humbling. It’s dangerous to assume you don’t have anything more to learn. That can be applied to self-identified “nice guys.” They view their behavior as the behavior of a nice guy, and any critique of their behavior as toxic can seem, to them, like an attack.

RKP: Sasha is being aggressively hounded, both online and off, and while she wants her earlier, uncorrupted fame back, she also recognizes “the value in being forgotten.” There are several legal cases pertaining to the “Right To Be Forgotten” currently underway, which largely call on Google to scrub certain images, videos or information from its search results. The trouble, though, is that the people fighting these cases range from victims of revenge porn to politicians accused of misdeeds.

As the line between curtailing the endless archive of digital memory and supporting the crucial call for collective memory (“never forget”) becomes increasingly muddled, I’m curious to know: where do you stand?

AM: This is such a complicated issue, and I don’t think it’s as simple as whether to leave these details online or to scrub them. They need to be taken on a case by case basis. In the instance of revenge porn, it is absolutely necessary that the images be scrubbed from the internet. That is a nonconsensual violation. In my opinion, what’s missing, right now, is not a standard policy but a trustworthy organization capable of determining whether something should be scrubbed or maintained. I don’t trust Google to serve as that organization—which seems where we’re at now—nor do I have particular ideas about who should take on this role. Is it the job of the state? It’s hard to trust the state. Corporations? Yeah, right—but I’m sure they’ll try. Perhaps this is kind of a non-stand, but I lean on the side of largely maintaining collective memory and [also] finding a way to create a commission capable of determining when it is best to forget.

RKP: I don’t want to give too much away, but at one stage in the book I felt a shift in my emotional landscape towards the men that mirrored Sasha’s—what she describes as “a little slug of sympathy… marking its trail.” And like Sasha, “I could have allowed myself this empathy, this softness, but it scared me.” As she reflects: “It is always easier—safer—to look away.” What made you decide to look?

AM: I’ve had a tendency, in my life, to eagerly sympathize with people who’ve hurt me and to think myself into their perspectives. I’ve had a father and a mother and stepfathers and stepmothers who have hurt me deeply, yet I still love them. This isn’t always a great habit to have in life—loving people who hurt you—but it can be helpful when writing fiction.

Loving people who hurt you isn’t always a great habit to have in life, but it can be helpful when writing fiction.

Throughout the process, I thought a lot about Kaitlyn Greenidge’s 2016 essay “Who Gets to Write What?” in The New York Times about creating a racist white character. She writes, “I was struck by an awful realization. I had to love this monster into existence.” And that seemed true of my book. I don’t like how these men act, but in order to write about them, I needed to love them at some level. And that’s what pushed me to look, because I think that’s what fiction requires—so long as it doesn’t completely center the “monster.”

RKP: Explaining his idea for The Atmosphere, Dyson “hopp[ed] from truisms to clichés to conclusions as if they were rocks in a stream.” As Sasha later says: “he aimed for the cadence of wisdom, wasted no time striving for content…Cadence dug a trench in the mind.” This emphasis on cadence is not just a cult-ish feature though, and belongs to start-ups and influencers alike—a “language of strategic confessions and origin stories” that I suspect is often the language I end up using online too. Why do things feel less true when they are stripped of cadence, even when we intellectually understand that cadence is often what obfuscates?

AM: I think we’re just accustomed to how certain arguments work. There’s a reason why we have English composition classes to teach basic structures of argument and paragraph development—we best internalize meaning when it arrives in a form that prioritizes information how we’re accustomed to reading. The same is true of the cadence of online speech. When someone begins a tweet, Freaking out that or I can’t believe or So excited to announce or No one is talking about or I’m tired of talking about or—you get it—we intuit how to absorb the information that follows. So, things that don’t fit those cadences sound less true, because the structure of the information is unfamiliar to us and is thus harder to absorb. It’s like if you went to see a stand-up show and the comedian speed-read their entire set off a notepad then rushed off the stage. Same words, but likely very unfunny.