interviews

Alissa Nutting on Sara Woods’ Sara or the Existence of Fire

Colin Winnette admires the writer Alissa Nutting, so he asked her to suggest a book that they might talk about. She picked Sara or the Existence of Fire by Sara Woods. Then they talked about it.

Alissa Nutting is the author of the short story collection Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls and, more recently, the novel Tampa. She was the winner of the Starcherone Prize for Innovative Fiction in 2011. She teaches at John Carroll University.

Colin Winnette: Can you give a brief (3-sentence or less) description to ground any readers who haven’t read or heard of Sara or the Existence of Fire yet?

Alissa Nutting: That’s actually more daunting than it seems — one of the things about this book that I love the most is its breadth…if you think of Fairy Tales having, say, a runway, the kind that planes would take off from, and Childhood having another runway, and maybe Mystery and Disappointment and Wonder and Dogs and Cookies and Worms and Parties and Haunting…I could go on. Flights depart and arrive throughout the book. One description would be that the book’s a sort of biopic of the main character Sara, whom we first encounter in childhood. In some ways the form of the book is set up like a documentary or a docudrama, with a running narrative that cuts to other characters for interviews and alternate perspectives.

CW: That’s a great introduction. The book isn’t linear, but each moment seems proximally connected to some shared organic center. There’s a strange logic to the book, that’s constantly being undone and built anew, reset. With everything coming and going in this way, how does Woods keep us from feeling lost or discouraged? If you’re going to spend all day in an airport, you might find a private(-ish) place to sit, or wander in loops all day — some way of making this enormous and disorienting place your own. Where did you build your home in Sara or The Existence of Fire?

AN: For me it was directly within the character of Sara, who tinges sadness with the most incredible humor…the poignancy is wrenching. So many lines in the book are one-liners and quotables, or just make you grab your chest. Like, “A dog can be heartbroken.” The first time I read that line I gripped my chest and nodded for about ten minutes. That happened all throughout. It’s a very validating book. An empathetic one. I think the episodic nature of the book is part of what’s so smart and comforting about the narrative…there’s the connective thread of that character. No matter what happens in the episode, Sara’s always still talked about or referenced in some way.

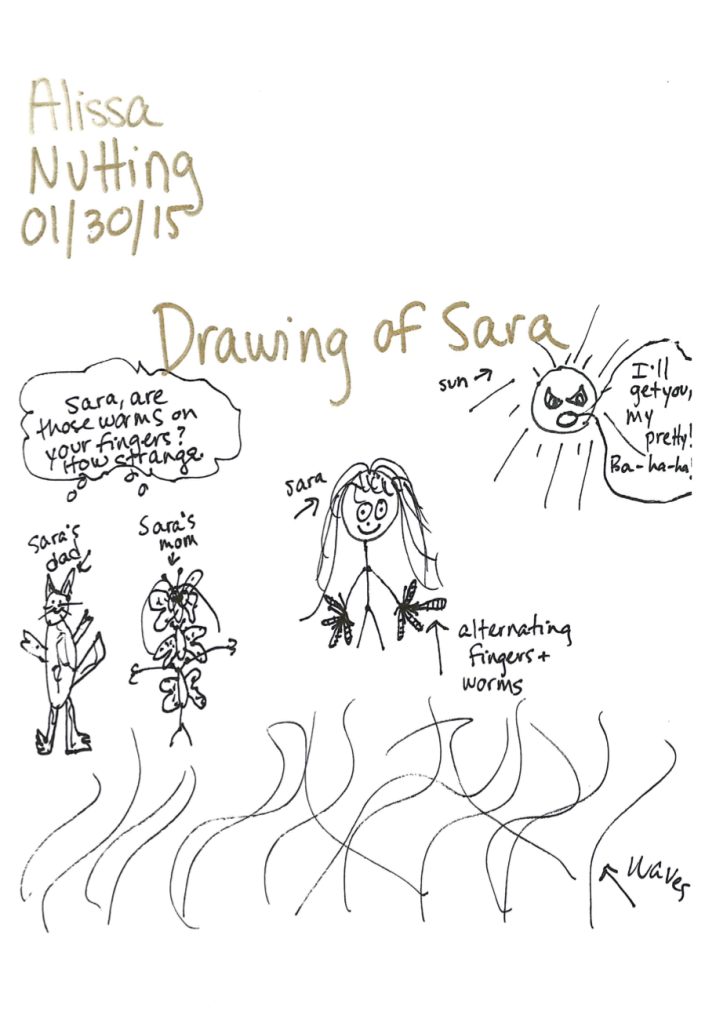

CW: Would you draw a picture of Sara for me?

AN: Okay. I’m teaching an undergraduate graphic novels literature course this semester, so I read the class pgs. 1–12 of the book and asked them all to draw a picture of Sara, too. (Those can be viewed here). My drawing is the one with my name, ha.

CW: Where did you find this book?

AN: I read [Sara Woods’] amazing book Wolf Doctors on the also amazing Artifice Books, and was very much all: MORE WOLVES!!! MORE POETRY!!! MORE SARA!!! This new book fulfilled all three of those requirements.

CW: Where did you find Wolf Doctors?

AN: In a word, narcissism. Poetry is one of the many pills in my anti-depressant arsenal. It just helps me cope. I feel like it’s bizarrely healthy, how these emotions and things are right there, and there’s enough space for those words to actually linger and grow and be showcased. It’s very religious for me, so I don’t read it daily, the way you wouldn’t want to do a sweat lodge retreat or something daily…you’d just get spent. Poetry spends me. In a good way. If I were a therapist I’d say I tend to write fiction because I don’t want to feel vulnerable. If I were a poetry critic I’d say I write fiction because my poetry is terrible. Anyway, I’d heard about the buzz for Wolf Doctors and had wanted to read it for a while, but as is my habit with poetry books I waited until I got sad to order it. It’s beautiful, and honest about the world in a way that isn’t restrained. It helped me. Beauty and honesty usually do.

CW: The book somehow felt both delicate and aggressive. There are obviously threats, fires, wolves, knives, etc. — but when I say aggressive, I’m thinking of the metaphors. Woods is constantly throwing down these gauntlets, “Sara’s father was a wolf,” “Sara was in a room full of hammers,” “Sara had an ocean inside her ears that wouldn’t go away.” These are the opening lines of just a few sections, and the poem spills out from each proclamation. Did it feel aggressive to you, or did you experience these opening moments differently?

AN: I felt both mesmerized, because of the magic of the events if they’re read literally and the images they trigger, and also very vulnerable. The text is very frank about how the danger and pain of life, and it’s coupled with these gorgeous, creepy descriptions (like a mother made of moths) that also really brought forward great positives about existence for me, like interest and curiosity. So for me it was a sort of comfort…this acknowledgment that the world can be so harsh and overwhelming, but that the silver linings are also quite real.

CW: When you think of the book, without picking it up to confirm, is there an image that comes immediately to mind? If it’s the moth mother, what does she look like? Gray and dusty? Backlit and white?

AN: Mothmother (I like it as one word) to me is a swarm of moths shaped somewhat like a roving droopy breast. The sound the swarm makes is the white noise sound of a sleep machine. But if there’s one image, without picking the book up, it’s probably an animation that is in the book yet isn’t, a composite aftermath of images and feelings: first the character of Sara standing on the beach as a young girl, then the image refreshes and the top half of her body is a wolf, then the image refreshes and she’s particles of sand, sort of like a swarm of moths I suppose (tinier, more particle-y) blowing away while a wolf sleeps in the distance on a beach towel, then the image refreshes and the sunset begins to shake out of place and we realize the sunset was actually a painting made of sand.

CW: Assuming the bit about the airport was metaphorical, where did you “set” this book? The beach? As you’re reading, do you place these characters anywhere in the world you know, or do you constantly readjust to keep up with the shifting world of the book?

AN: That’s a good question — I suppose because of the beach references parts of the book felt coastal, but because of wolves I also thought fairy-tale forest. Not in the sense of make-believe, but in the true fairy-tale sense: that life is filled with splendor and horror both; neither is available for individual purchase. The book kept reinforcing that to me in such a genius way.

CW: What feeling do you most associate with this book?

AN: The strongest feeling I associate is endurance…this capacity that tends to turn on hopeful lamps inside me, that things continue, for us and with us and after us, no matter our pain. And with all its unexpected hilarity about truly heavy subject matter, the feeling that sits with me after is that I will reach for this book a lot throughout my life when I need that empathetic lift without the sugar coating…I’ll reread it a great deal. When I was reading it I felt the discomfort more acutely — the discomfort of this book can be fast-acting, like a microwave, while the hope within the text is more of a crock pot. By the end of the book you do have a fully prepared, family-sized serving of hope — a particular flavor that is seasoned by unflinching veracity. Delicious.

CW: Would you leave us with a short passage from the book? And would you be willing to record yourself reading that passage?

AN: I recorded this for you today.

Author photo courtesy of Aaron Mayes