interviews

Allegra Hyde on Seeking a Better World

The author talks utopias, Shakers and white spaces.

The narrator of “Shark Fishing,” the first story in Allegra Hyde’s debut collection Of This New World, asks herself, in one of the book’s most moving moments, “Who was I except someone who’d always been willing to dream?” The collection finds this narrator as it finds many of its protagonists: trying to navigate the knots between intention and result, promise and fulfillment, resistance and pragmatics. Each story, in its own way, is asking deft questions about the possibility of improvement, both on the micro and macro level, and where other writers could have fallen into didactic or moralistic traps, Hyde’s stories move effortlessly and gracefully, never once causing the reader to feel as though she has her authorial thumb pressed on the scale. It’s no surprise, then, that the University of Iowa Press saw fit to award Of This New World the 2016 John Simmons Short Fiction Award, a prestige visited upon, in recent years, writers like Marie-Helene Bertino, Jennine Capó Crucet, and Chad Simpson.

It enriched my reading experience even further to talk via email with Allegra Hyde about this percipient, lush, and hopeful set of stories.

Vincent Scarpa: What about idealism and its relationship — or lack thereof — to paradise felt ripe for exploration as the writer you are? Was there something you were setting out to magnify or explode from within that space, or was your approach a kind of neutral inquisition?

Allegra Hyde: Utopias — their pursuit and implementation — have obsessed me for many years. Or maybe haunted is a better word. I think it has a lot to do with my own perfectionist tendencies. I’m drawn to examples of people trying to live up to an ideal, in spite of the challenges, because I relate to that hunger for realizing a vision in the face of practical concerns.

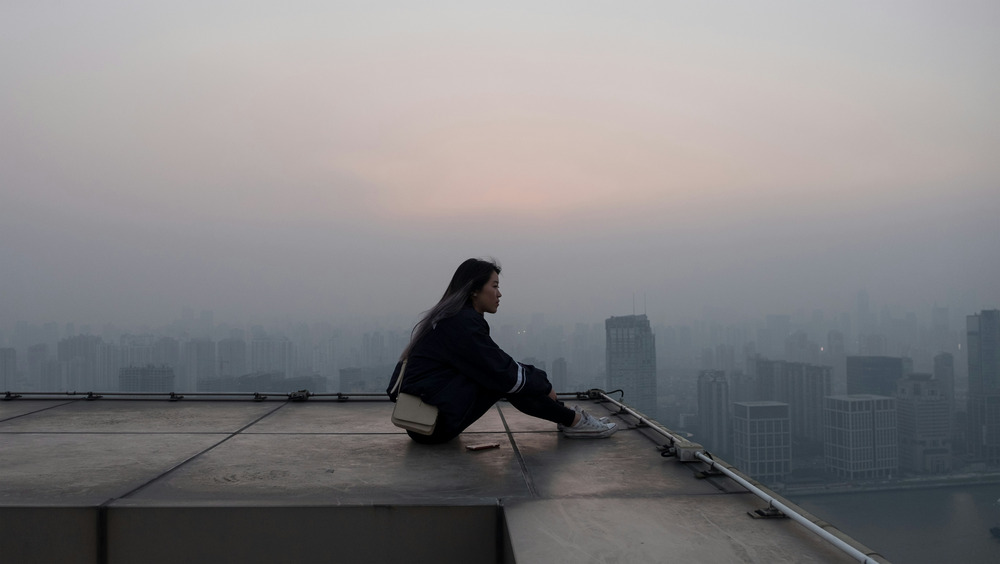

I also think we’ve entered a ripe cultural moment for utopian thinking: sea levels are rising, a right-wing demagogue could win the US presidency, scenes of violence flood our news channels. We have an opportunity, here and now, to choose between despairing over an apocalyptic future or actively considering what a better world might look like — even if it seems pie in the sky — because we’ll never reach that reality without first daring to imagine what it might be.

We have an opportunity, here and now, to choose between despairing over an apocalyptic future or actively considering what a better world might look like…

VS: The narrator of “Free Love” says, of her off-the-grid hippie father’s plan to live in a houseboat and sail the world, that it sounds “spectacularly imprecise, gloriously underdeveloped.” This seems like the nature of most plans toward utopia, and I wonder if you think it’s the chief reason they fail. Or is there some larger force of impossibility one must contend with when trying to build a utopia, no matter the scale?

AH: I think the Anna Karenina principle applies here: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” An imprecise execution of ideals might spell the demise of some utopian endeavors, but others have been spectacularly organized. Take the Shakers: at the height of their influence in the mid-nineteenth century, they had 6,000 members in something like twenty different communities. In Shaker life, each day was carefully orchestrated; the spiritual attitude they brought to labor made them economically viable. There was just the question of sex. How does an abstaining population carry on? Recruitment and orphan adoption can only go so far. If old age didn’t exist, maybe the Shakers would still be going strong. But they’re down to three members up in Maine. The aspect of their ethos that made them so productive — the curtailing of human desire — also made their endeavor ephemeral.

I say ephemeral instead of “a failure” because I have trouble applying the latter to these types of social experiments. Although a utopian community might not last in a physical sense, its espoused ideals may stick around longer than its members and have a far-reaching impact on the broader society. The Shakers, for instance, had all these breakthrough inventions — like the clothespin and the circular saw — which we still use. And their design principles of simplicity and efficiency are still visible all over New England.

Or — returning to “Free Love” — consider the proliferation of hippie communes in the 1960s. Most back-to-the-landers eventually went back to more normal lives and jobs, but their ideals of sexual fluidity and their respect for nature still continue to resonate. Utopian experiments, viable or not in the long-term, can still influence mainstream culture.

VS: Something I admire about these stories is that so many of them have an active political consciousness. I don’t know if you agree, but that seems to be something that’s all but vanished from so much of contemporary fiction. I’m not sure if it has something to do with the fear of being didactic or not, but it was refreshing to see you take on issues like global warming, PTSD, immigration, and so forth. Did you have any trepidation in tackling these issues? Is there something unique to fiction that allows such exploration?

AH: I did not set out to tackle political issues. I would never want to write — or read — fiction that tries to tell a reader what to think. I did, however, set out to write stories that felt meaningful. If I’m afraid of anything as a writer, it’s of becoming frivolous and self-indulgent, especially since I spend so much time alone in a room making stuff up. The gift of fiction, however, is that it can mirror back aspects of our society that might otherwise stay hidden. Making PTSD present in a story, for instance, is about recognizing this issue as part of the fabric of our daily lives. Twenty veterans a day commit suicide. My story “VFW Post 1492,” about a depressed and disabled veteran, isn’t taking a political stance so much as bearing witness to our modern reality.

VS: One of my favorite stories in the collection is “Shark Fishing,” which is a clear-eyed look both into the way colonization calibrates a place forever and at activism faced with the dangers of being a variety of colonization itself, despite ostensibly good intentions. Like “Delight,” another terrific story, it made me think a lot about the fact that utopian visions are by no means universal, and that a genuine desire to do good can so often be at cross purposes with what is presently capable. I’d love to hear you talk a bit about how this story came to be.

AH: When I was twenty-two, just out of college, I went to work at an environmental leadership school in the Bahamas. It was an inspiring place, one that echoed my own environmental ethics through its educational work, scientific research, and sustainable infrastructure. However, as I began to learn more about the local history — a history that included Puritan settlers, vast plantations, and luxury resorts — I began to see a pattern emerging. Initiatives on the island often started with great promise but ultimately ended in exploitation. I began questioning whether I was participating in the continuation of that cycle. I believed — and still believe — that it’s important to address climate change with the utmost urgency, but I also believe in respecting the integrity of an existing culture. “Shark Fishing” was an effort to explore the nuances beyond obvious labels of right and wrong.

VS: I was thinking of the writer Jim Shepard — one of my favorites — as I read these stories, without having yet seen that he in fact is a favorite of yours and gave such a lovely blurb. I think he came to mind because so many of the stories here, like Shepard’s stories, feel built on a solid foundation of research — whether it’s the history of Eleuthera in “Shark Fishing,” the botanical language of “Bury Me,” or the exquisite details of Mexico we find in “Flowers For Prisoners.” Can you talk about the role research plays in your writing practice? How much do you do and when is enough? How do you decide what makes it into the story and what doesn’t?

AH: I had the good fortune to study with Jim Shepard as an undergraduate. He was a brilliant and generous teacher, and he implanted some ideas about writing fiction that continue to define how I work. Having once caught a glimpse of his writing desk — surrounded by books and research materials — I realized that a short story can be the synthesis of so much unseen knowledge. When I research now, much of what I learn doesn’t make it onto the page. Nevertheless, it still feels important to hold a breadth of information in my mind as I write — whether it’s botanical language or Mexican geography — because research can infuse a story’s style and structure in profound yet invisible ways.

That isn’t to say the research that makes it onto the page isn’t significant. I try to use the material that will encourage a reader to trust me, to follow me into a fictional reality. I also sometimes share information in stories that seems too interesting to be buried by history — though that can be a slippery slope.

VS: I’d be remiss not to talk about structure, because these stories are so elegantly and masterfully architectured. Sometimes I think a good short story can mask a somewhat flimsy or clunky structure, but I think great stories are always working on the level of the line and the level of the whole. This is something I think you do so well in a story like “Ephemera,” where we’re switching between three distinct protagonists with three distinct varieties of loneliness. I wonder if you could talk a bit about story-building, and if structure is something you have an idea of going in or if it’s something that the movement of the language, line by line, necessitates?

AH: During the drafting process for “Ephemera,” the story’s structure evolved organically alongside the progression of plot and character. There was, in other words, an editorial feedback loop. The structure changed line by line. However, for a story like “Americans on Mars!” I went in with a distinct structure I wanted to pursue, having been inspired by the work of Amy Fusselman in The Pharmacist’s Mate (which I highly recommend). So in that case, an existing structure dictated the way the narrative emerged.

Regardless of how a story comes into fruition, the final stages of revision are a very visual process for me. I have an art background, so I tend to bring elements of design to my stories. For a piece like, “Ephemera,” I became very conscientious of the shape of the braided narrative, the way paragraphs of differing lengths played against one another, the harmonies of text and white space. To speak in generalizations, I admire the talent poets have at positioning text. They are often more aware than prose writers are of how white space can be a living, breathing part of a piece. With prose, conventions dictate that your writing is essentially a word soup that gets poured into the shape of a magazine page or a book layout. I tend to write with lots of paragraph breaks in my stories, in part because its something I can do as a prose writer to influence the visual structure of my stories within the conventions of the genre.

VS: You’re such a great practitioner of the short story. I’d love to hear other practitioners you admire, and also what you’re working on next, now that the collection is in the world.

AH: I’m bursting at the seams with my admiration for Jen George. Her first book, a collection of stories called The Baby Sitter at Rest, is out this October through Dorothy, a publishing project. George writes about the threshold between youthful naiveté and adult despair. Her fiction is vivaciously detailed, fierce and funny, and deftly captures that sense that everyone other than you knows what’s going on. I want everyone to read this book!

In terms of short story standbys, Amy Hempel’s writing has taught me a lot. The architecture of her fiction always works in elegant symbiosis with the story being told, and she’s so good at blending fact into fiction. Also, once at AWP, she touched my arm as she attempted to navigate a crowd on her way to panel. This felt like a blessing.

Of This New World may be out of my hands and loose in the world, but it serves as the foundation for my next project: a novel that expands and reworks “Shark Fishing.” Though this story is the longest in the collection, I haven’t been able to shake the sense that there’s more narrative territory to explore. So I’m returning to the Bahamas, in a way, trying to continue addressing climate change and what it means to seek a better world.