Books & Culture

An Elegy for Ecuador

In The Revolutionaries Try Again, Mauro Javier Cardenas allows inventive language to take center stage

Mauro Javier Cardenas’s first novel, The Revolutionaries Try Again, links the stories of three graduates of San Javier, an elite prep school in Guayaquil. Antonio, Leopoldo, and Rolando were all once part of the same Jesuit volunteer group, all idealistic, all ambitious, and, by the novel’s start — and certainly by its finish — they all have had that idealism and that ambition suffocated.

But more interesting than any aspect of The Revolutionaries Try Again’s plot is its language, which also looks rather conventional, at first; then the sentences start to lengthen, and we run into Spanish phrases here and there, and some theatrical dialogue; by the end, the reader’s wavering between pages-long sentences and phrase-fragments cordoned off by dashes and slashes.

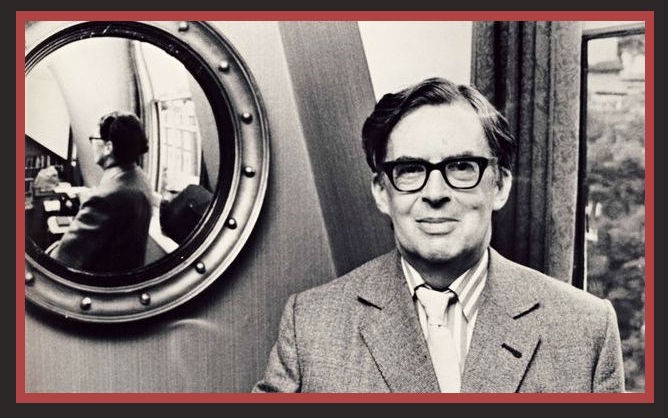

Cardenas seems to have telegraphed his influences. A quick Googling will unearth his interviews with literary heavyweights, particularly ones known for dense, monologue-driven novels, where politics press upon the lives of individuals: Laszlo Krasznahorkai (Hungarian), Antonio Lobo Antunes (Portuguese), Horacio Castellanos Moya (Salvadoran), among others. Enlivened by foreign influences — including those of its Ecuador-born author — the English of The Revolutionaries Try Again expands and contracts, twists and deforms. In every sentence is a churning mind. Words tumble on, and the experience of reading begins to resemble the the sensation of thinking, of remembering.

…what Antonio will remember of that spiritual retreat is that after their evening Mass, disregarding Father Lucio’s warning that no one was to leave their rooms upstairs — stay alone with the lord, Drool — Antonio escaped from his room and evaded the pack of Dobermans that had been unleashed by the priests and sneaked inside Leopoldo’s room, where late into the night they argued about what god wanted from them and we have a responsibility to him, Leopoldo says, the lord has chosen us, Antonio says, the Dobermans barking outside Leopoldo’s room as Leopoldo raises his glass toward the light and says we must be transparent like this glass so that god’s light can pass through us.

This is a typical sentence not only in its form — how it meanders through sense and memory, its plurality of voices, its sheer length — but also in its nostalgic treatment of religious belief and friendship. And nostalgia, of course, follows loss. The Revolutionaries Try Again is about lost faith, and not just in God, but in institutions, such as religion and government, and in people, such as your friends and yourself.

Through Leopoldo, who grows up to be a government economista, we get scenes of bureaucratic absurdity. Antonio presents an alternative: as soon as he graduates from San Javier, he leaves for the United States. Antonio is the novel’s central character, and his biography resembles his author’s: both from Guayaquil, both of their fathers were ministers in Cordero’s government, both attended San Javier and Stanford. And Cardenas says that he, like Antonio, planned to return to Ecuador and run for office. But instead of returning, he wrote a novel.

Antonio, at the novel’s start, has all but given up the dream of his triumphant return. (Now he’s a writer who “imagine[s] the possibility of deforming American English as revenge for Americans deforming Latin America.”) Leopoldo phones Antonio on an impulse and convinces him that they should run for president like they had always talked about. It’s a dramatic instigating event, the fateful call made possible by a lightning-struck payphone, a scene that seems to suggest that we’re in for some sort of magical realist political thriller. But no, this is literary fiction, a genre whose authors only rarely deign to tell an exciting story. So The Revolutionaries Try Again is a a sort of mocking title (though it suggests a harsher irony than the book actually possesses). It’s not about a revolution; it’s not even about trying, certainly not trying again. Antonio and Leopoldo’s prospective candidate is another San Javier grad, a rapist from a rich family, who doesn’t even care about politics. They all chitchat, go to parties, and spark no upheaval. The Revolutionaries Try Again doesn’t quite fulfill the drama that its opening seems to promise, but nor does it get mired in the doldrums of typical lit-fic plotlessness. The book succeeds because the mechanics of the mind, much like those of politics, tend to whirl in place rather than move forward. For a novel about stifled ambition, this form fits.

Or these forms fit, that might be more accurate, because the novel’s always shifting; its syntax twists and untwists; lines stagger down the page; two chapters are in Spanish. But the form that makes the strongest impression first appears in the Rolando and Eva chapters. Their story takes up far fewer pages than Antonio and Leopoldo’s, but when the novel’s focus trains on Rolando and the two women whom he’s obsessed with (Eva, his lover, and Alma, his sister), Cardenas writes in his least conventional mode.

…the surface of the road on the way to Eva’s house shifting abruptly from pavement to gravel to craters that rattle the bus that’s speeding by with a hand-sized flag of El Loco attached to its antennae that sounds like the shuffling of cards — which reminds Rolando of nothing — of his father who never played cards backgammon chess — switching off the headlights as he parks by Eva’s house — to remain silent is to give the impression that one wants nothing — to shut off the lights in one’s house is to give the impression that one wants — a surprise? — shut up — that one is asleep — that one is embracing someone other than Rolando Alban Cienfuegos carajo — stop that — that one has shut one’s eyes to the world — let it rot Rolando — winning the chess championship at San Javier three years in a row but his classmates turning it into a joke — Gremlin eat Queen ha…

It’s a destabilizing effect, temporally distorted and fragmented, fitting for the unstable Rolando. (In his first appearance, after his father tells Antonio and Leopoldo that he is starting a radio station, he lashes out at his former classmates, screaming that they are “thieves.”) Eva wants him to use his station to produce and broadcast political radio dramas, but Rolando rather play Ricky Martin, because, he believes “nothing changes without violence.” Violence looms over these chapters, which do not only stand in contrast to Antonio and Leopoldo’s on stylistic grounds. This is how the moral weight of the novel starts to accrue, with the human consequences of systemic corruption made manifest.

A self-consciousness about literature and literary convention; a distortion of linear time; a depiction of reality as fragmented, using various, internalized, questionably-reliable perspectives, as well as grammatical and syntactic irregularities: this sounds like a Modernist novel. Cardenas uses the trappings of Modernism to traditionally Modernist ends — mirroring the workings of consciousness, and depicting a society, reeling from violence, that has lost faith in itself — but The Revolutionaries Try Again is set in a country and time that we don’t normally associate with Modernism: the Ecuador of the mid-90s, in the months leading up to the demagogue “El Loco” Bucaram’s election.

So, in a sense, this novel belongs to the past—to Ecuador’s history, and to Cardenas’s life, and to the innovations of Modernism. But I hope, as thousands migrate northward, that this novel belongs as much to the future. Wouldn’t that be fantastic, if this dense, brilliant, bilingual novel by an immigrant is what the future of American literature looks like?