Interviews

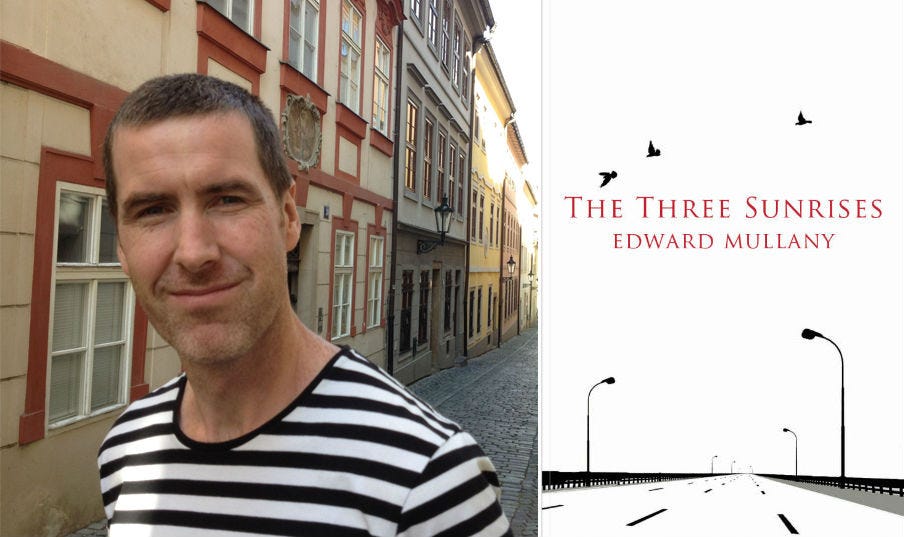

An Urgency in Faith, an interview with Edward Mullany, author of The Three Sunrises

by Annette Hakiel

Edward Mullany’s third book, The Three Sunrises, will be published this month. A collection of three novellas, it is the final installment in a trilogy that began with If I Falter at the Gallows and Figures for an Apocalypse (Publishing Genius). Mullany is also the artist behind the online comic strip Rachel & Ben, which appears each Saturday at the arts site Real Pants. His writing has a philosophical and religious bent to it, much like his artwork. For several weeks, Mullany and I exchanged emails about his haunting new book. We talked about death, the afterlife, and the similarities and differences between ‘madness’ and mental illness.

Annette Hakiel: Your first two books (If I Falter at the Gallows and Figures for an Apocalypse) focused on poetry and micro-fiction as a form. What inspired the move towards the longer and more narrative forms you use in The Three Sunrises?

Edward Mullany: The voice that started talking out of me when I wrote The Three Sunrises had a lot to say — more, maybe, than the voices that spoke from me when I wrote the first two books. That is one way of looking at it. This doesn’t mean I was letting the voice talk willy nilly, or to ramble. There has to be a degree of control involved. A writer doesn’t control it, exactly, but hears what it is saying in absence of language, and then translates (or puts down on paper) that voice, in language. That is the difficulty, the art. The difference between someone who is rambling and someone who is practicing an art is that the artist shapes a chaotic impulse into order, whereas the person who rambles does not. (I believe this is true even when considering a writer like Kerouac, who described much of what he did as spontaneous writing). Talent always involves technique.

Also, though, to answer the question another way — I think I simply grew into the longer form. Meaning, until I wrote The Three Sunrises, the shorter form seemed most natural to me. Which might mean that the ‘voice’ I hear (as a muse or impulse or what-have-you) is always the same, and that what in fact changes, over time, is my mode of expression.

AH: As your mode of expression has changed, are there any themes or overriding concerns that you find have persisted in your work? For example, your books seem to convey a powerful sense of loss, or imminent disaster. Is this something you attribute to your voice/muse, or is this something you feel you have control over as an artist?

A writer’s obligation is to technique. Everything else arrives on its own.

EM: The themes that persist in my work I do attribute to the voice I hear, though I don’t think that voice operates entirely outside of my personality. By which I mean every artist’s muse is related to that particular artist, and maybe is a sort of psychic or spiritual appendage in which the artist has buried all the preoccupations that are too dangerous for him or her to encounter directly. I say “dangerous”, and I mean that in a relative way (for suicide or self-harm is the only consequence of these preoccupations that I can think of that could be practically described as dangerous). But I do think that the repressing or burying that almost all people do, and that artists more commonly allow themselves access to, suggests that something is at stake. The important thing to notice, in regard to the work itself, is that you don’t think about what these preoccupations are as you work — they simply arrive there, in the shadow or ghost of the plots that you write. A writer’s obligation is to technique. Everything else arrives on its own.

AH: Who do you consider to have influenced you? Is Paul Auster an influence?

EM: Paul Auster is an influence, though he’s maybe not the writer who has influenced me most. Of his books, I’ve read only The Music of Chance and the first two books of The New York Trilogy (which I love, even though I haven’t finished it) and which I knew about and thought about long before I began reading it. What I mean is that I’d heard of The New York Trilogy before I ever had a copy of it in my possession, which I know is not unusual (I’d heard friends discussing it or recommending it, the way people do). And during that time, whenever I heard it mentioned, I would think about the book and would wonder about it. And what I imagined that book to be, before I obtained a copy, had an effect on me, even if what it eventually revealed itself to be, when I began reading it, was different than what I’d imagined it to be.

Blake Butler tells a story (I think in his memoir about insomnia, called Nothing) about how he once kept a copy of IT by Stephen King in his bedroom, when he was a teenager, and how he never actually read the book but let it sit there in his room — maybe thinking he was going to read it, but never getting around to it. And so the book, as an object, assumed a kind of haunting power. And he describes how that situation or relationship (between him and the book, or between him and what he knew or imagined the book to be about) came to represent something just as potent for him, creatively or psychologically, as if he had in fact read the book. There is an influence, then, that can be a sort of imagined influence — between the person who feels it and the work of art that precipitates it. And the tone or vibe of this imagined influence is different than the influence that would result from a more direct contact with the artwork in question. Which is weird, I think, but also wonderful. Because it reveals how influence itself is a complex, varied thing.

AH: I find it very interesting about the concept that an artwork or book is significant perhaps just as much as the words within it. Perhaps this is true also of religious texts. How has Christianity influenced your work? The bible? The idea of the bible?

EM: There’s a branch of study in Christianity called eschatology (from the Greek — the study of ‘end things’, or ‘last things’). I feel like I’m a religious writer insofar as I’m an eschatologist. This doesn’t mean I think I’m a good person (I don’t), but rather that I tend to observe the world through this theological lens. It’s a consequence of how I was raised, but also of what I’ve come to believe. I qualify it this way because I know it isn’t true that how a person is raised always corresponds to that which a person comes to believe. A person can be raised Catholic, and, by adulthood, identify as an atheist. And faith cannot reach its fullness, either, unless it is doubted.

There is an urgency in my faith, even if my faith is also measly and inadequate.

My point is that Catholicism colors most of my conscious perceptions. Or, I should say, it colors the conscious processing of that which I perceive. Suffering has meaning to me mainly because I understand it in the context of what I believe about human history. If I didn’t believe in the Resurrection — that God was incarnate in the world, as the second person of the Trinity; that he suffered and died, and that he, the Son, was resurrected — I would be in despair more frequently than I am. There is an urgency in my faith, even if my faith is also measly and inadequate.

I recognize the arguments against faith in general, and against Catholicism in particular. But I’ve made my peace with those arguments. Or, rather, I’ve made my peace with allowing them to exist in a space in my mind that is reserved for things that I won’t be able to resolve, or reconcile. I accept that this is part of human experience — not being able to understand, or comprehend, paradox.

This is a long way of saying — yes, Christianity has influenced my work.

AH: I think I might ask something about mental illness and your book. I know I was coming out of psychosis when I was reading it, so my memory of it is shaded by voices, as well as the topic of mental illness (in terms of the Legion figure…I’m wondering if he’s mentally ill). Do you mind talking about that? Has your life been affected by mental illness?

EM: I think mental illness is thematically present throughout The Three Sunrises, though I would use the term “madness”, as it is less clinical, and therefore does not close itself off as conclusively to the spiritual realms to which I believe it is related. By madness I mean the consequence of not knowing whether that which you are experiencing is actual, or an hallucination — real, or paranoia. And by “thematically present” I mean that I think madness is the state in which all of the characters in my book at one time or another find themselves. And I think that this theme arrives in my work as a result of my own preoccupation with the fundamental problems of existence.

I say “problems”, and I guess you could call them that, though I don’t think, in the end, I actually see them as problems. Or, rather, I see them as problems only when I view them through that very human perspective that is not, to my mind, separable from original sin. I mean that even under circumstances that might be described as ‘fine’ or ‘everyday’, humans tend to recognize existence as a ‘problem’ because we are a fallen creature. We are no longer in paradise. And we have ‘knowledge’ — can observe, judge, and compare. Which is one reason we suffer. The further we return to a state of not wishing for that which we do not have, the less of a ‘problem’ existence becomes. A Christian is also a Buddhist in this sense.

The character in the novella, Legion, is perhaps the most obviously mentally ill. And yet is he mentally ill? The title of the story, as well as the epigraph from which the title is taken, suggests that he is not ill, but is, rather, demonically possessed. Which one might say is distinct from mental illness. In the former, maleficent spiritual beings take possession of one’s body, in order that they might have one’s soul for eternity. In the latter, the conditions of life (or of a personality) cause chemical imbalances in the brain; the soul is left untouched. Outwardly, the two cases might look similar. But fundamentally they are different.

I can’t speak to whether my intention, or design, with respect to Legion, succeeded. And I don’t mean to suggest that I had much of an intention or design to begin with. I do think all art is ordered — that it contains order within it — but much of the intention that reveals itself through that ordering originates in the subconscious. You see what you have made, and what you are making, but you don’t see it fully until you are finished. And even then you can never quite apprehend it.

AH: Death seems a prevalent theme throughout these works… what do you think of the idea of an afterlife — one that your own soul might possess as well as those of works of literature? My first impression when reading The Three Sunrises was that, with the dead mother figure, it was a signal towards a more (godless) existential philosophy (ala Camus’ The Stranger). Were ideas of fate or free will at work in your mind, even in the background, while working on this book? And finally, was it difficult to write the ending?

I tend to speak of my personal experience with mental illness in terms of religion, which I guess is weird?

EM: I wanted to say more about mental illness (in answer to your previous question), but I wasn’t sure how. Let me add this. I tend to speak of my personal experience with mental illness in terms of religion, which I guess is weird? I’m not sure exactly. I have a difficult time differentiating between guilt (which I think of as a genuine spiritual condition) and self-loathing (which, at best, is an unhealthy aberration of that spiritual condition). I often don’t know, in the course of any day, if it is my conscience that is speaking to me (for the right reasons) or if it is my mind attacking itself, like a poison. It’s a cause of distress and unease for me. And I think that’s probably another reason why I write what I write about. I often feel confusion, paranoia and sorrow.

A friend who has read the book has described it as “apophatic”, which refers to the belief that God can only be known to humans through negation — through an articulation of what He is not. I like this description, and I mention it in response to your question — “what do you think of the idea of an afterlife” — because I think it suggests that I do believe in an afterlife; insofar as a belief in God (even one that depends on knowledge obtained only through negation) implies that one also believes in an afterlife. And I do believe in an afterlife, though the Catholic theology I would profess does not happen to be apophatic (it is the opposite, in fact — cataphatic). But the way a writer writes, and what that writer believes, do not always mirror each other precisely.

It is through this of lens belief, anyway, that the book’s preoccupation with death might be understood. The presence of death is complicated by the presence, or possibility, of what awaits a person after death. This is evidenced by the reappearance of the mother (in Legion) after she has died. It is evidenced also by the ‘undeath’ of the skeletons throughout The Book of Numbers. And it is evidenced, finally, I would say, in The Three Sunrises (the last novella), by the presence of the Castle, and the epilogue that follows the narrator’s experience of the Castle. I can’t tell you exactly what the Castle means, because it is too ambiguous an image to surrender itself completely to comprehension, but I think its appearance in the story is infused with the supernatural. And throughout the book, I think, the horrors of the physical world are related to some groan, or mumble, that has its origins in a spiritual realm. In this way, temporality is harangued, even assaulted, by the nearness of eternity.

AH: The book is composed of three different novellas. Did you intend for them always to be together as you wrote them? Which one did you write first? What about the shifts in perspective?

EM: I wrote the three novellas during the consecutive summers of 2012, 2013, and 2014. I wrote The Book of Numbers first, though its placement in the book is second. I didn’t know what it was when I wrote it. I thought it was pretty strange to read, and I was conscious of how strange it had felt to write. So I thought at first that maybe it would not be published, and I was ok with that. I mean that if I had not written the next two novellas, and I hadn’t then seen The Book of Numbers in light of what those other two novellas were, not submitting it for publication might have seemed natural. But I see now that the meaning of the entire book (not just that novella alone) arises partly from the way the three novellas interact with each other. Their similarities and differences form a terrain that is made of the same dirt.

AH: I find writing can sometimes be a solitary exercise. Have you found a community of writers you share ideas with or respond to?

EM: Different parts of the internet are where writers respond to each other now. I mean instead of gathering in bars or wherever they used to gather, though they still do that too. But I think solitude is good for writers, because it allows them to confront their own conscience, and to dwell in their own imaginative space long enough that, when they approach the actual ‘making’ or ‘doing’ of their art, they do so in a way that is personal and original. Too much solitude can be bad, of course, but only insofar as the effect of that solitude is loneliness, as opposed to some inward, creative dreaming.

As a person, for relief of solitude, you need friendship and love. But in your capacity as a writer, what you need when you’re not writing are books to read, or other forms of art to encounter, so that, during the times when you have written all you can, your mind is absorbing things it can respond to, subconsciously, when you return to your work.

I guess it is possible to imagine a sort of hermetic writer who is holed up in a cave somewhere, writing not to be read by others, or for posterity, but only as a form of time-passing, or devotion. That kind of writer might have no need for reading, or for the history of art. They would be interested more in a conversation with themselves, or with God, conducting it in a language or with symbols that might be childlike and artless, significant only to themselves. But most writers are interested in artifice — in creating a thing that is separate from themselves and that reflects the times in which they live; a thing that is created with a consciousness of what previous writers have already done, and that speaks to other people (readers) in a way that feels not like journaling, or hymn-making, but like a dramatization of reality that has been arranged, or ordered, with an inward coherence, a design.