interviews

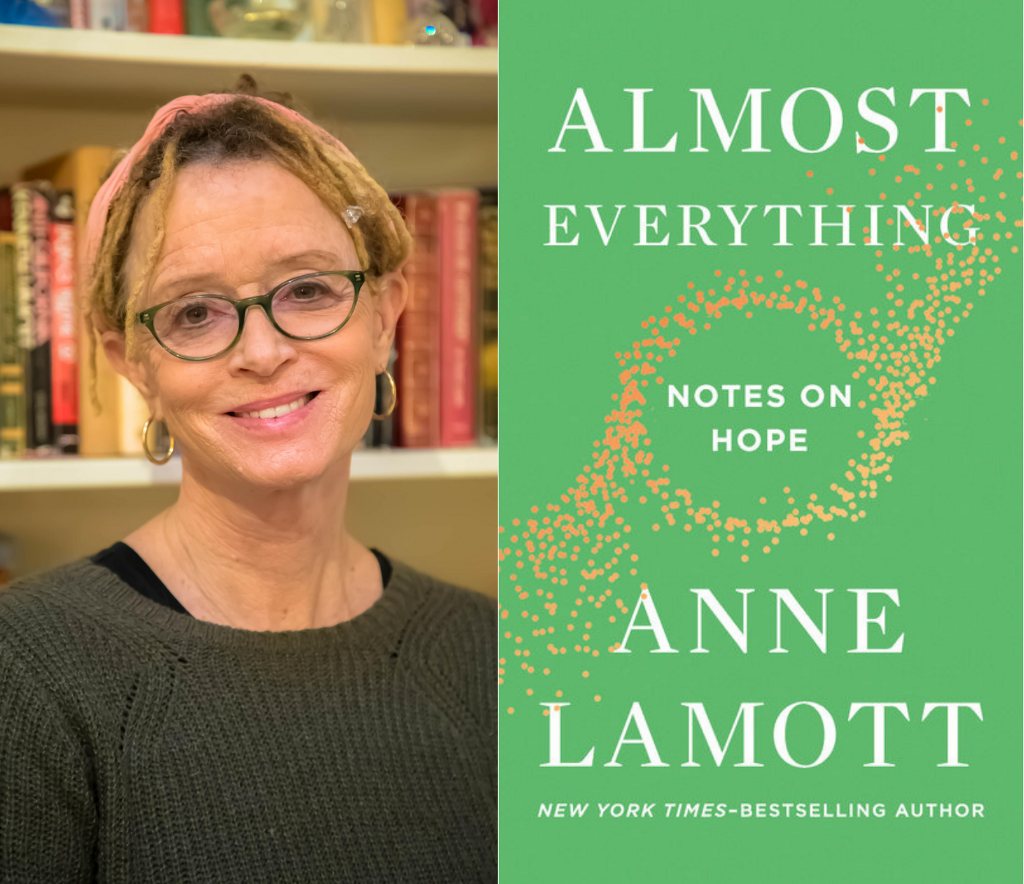

Anne Lamott on How to Hang on to Hope

The author of ‘Almost Everything: Notes on Hope’ on stories that save us

If the bleak daily news cycle has you grasping for some comfort, you’re not alone. Google searches for “anxiety symptoms” hit an all-time high in October, according to Google Trends. With the swearing-in of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court and news that climate disaster is closer than we thought, hope may be the farthest idea from our minds.

It’s easy to assume that the only people who possess cheery thoughts like hope are those willfully not paying attention. But as Anne Lamott shows us in her essay collection, Almost Everything: Notes on Hope, faith can exist side-by-side with uncertainty, as humor can with doom.

Almost Everything, as you might expect from the title, includes a little bit of everything, connected by the central threads of humor and resilience against adversity. The essays in the collection are small morsels, offering tastes of Lamott’s wisdom about enduring themes like faith and family.

The rest of Lamott’s oeuvre spans decades and genres. Her first novel, Hard Laughter, was published in 1980. Since then, Lamott has published 18 books, including novels and essay collections. While her welcoming style often uses wit, she has covered topics, like alcoholism and cancer, that many other writers find difficult to render on the page, much less joke about.

It’s more important than ever to find humor in the darkness. As many of us stand up to resist ingrained systems of oppression, whether in the voting booth or in our daily lives, with each setback, it becomes easier to see the problems of our time as insurmountable. But if we lose hope, we’ll stop fighting, and our struggle will have been for nothing.

Almost Everything offers a dose of levity, but it doesn’t stray from the truth. At a time when many of us, myself included, require that kind of irrepressible wit just to get by, I had the privilege of talking to Lamott about her new book, writing, and staying hopeful in these uncertain times.

Rebecca Renner: Almost Everything is about hope. Recently, with the news about politics and the environment, it has been hard to find many things to be hopeful about. How do you stay hopeful? And how to you keep writing?

Anne Lamott: I get just as freaked out as anyone. I have a 9-year-old grandson who will be 29 at the latest when they say that huge evidence of climate disaster will appear — although it will probably be earlier. And so I grieve. But I also say with confidence that we do what we can. I send people money. I march, I donate, and I try to focus on the solution.

I have a lot of faith in God and in community and in goodness, the incredible goodness of the American people. But I also have a lot of hope in science. People’s response will be profound and astonishing.

I have a lot of faith in God and in community and in goodness, the incredible goodness of the American people. But I also have a lot of hope in science.

RR: Has the grief you mentioned ever stopped you from writing? Have you ever had one of those days where it’s just too much?

AL: Oh sure. Of course. Who hasn’t? But it’s usually because I see the news, and I make up stories that are just catastrophe thinking. I grew up with a lot of anxiety and fear. My parents were unhappy. One of the ways children cope is to do this kind of prophylactic catastrophe thinking, to imagine the worst.

There’s this funny 20 questions, like the 20 questions of alcoholism you’ve probably seen. Now this is the 20 questions of thinking. It says things like: Do you ever think alone? Do you ever lie about your thinking? Has thinking ever kept you from going to work? So I try to separate out what is true, which is to say what is real, what is science, what I can do to help, and what are the stories I’ve just made up that in my childhood seemed to comfort me, paradoxically.

I’m beyond grateful for the huge new energy you see from people in their twenties, which you didn’t see 20 years ago. You know, I felt like women were expecting us old feminists to march for women’s rights and abortion rights, and now people are really involved again. At the marches, it’s half younger people now.

There’s been a generational coming together, and people are pushing up their sleeves and staying informed. That’s all you can do. We stay aware. We do what we can. We show up. You know what? We do what’s possible.

RR: Do you think there is a healing quality to writing? Can writing help us keep moving forward?

AL: Of course it heals the writer to get to take [stories] from their rat exercise wheel of a mind — if they’re anything like me. You get to express it, to take it from terror to creation. If I write something and give it to you today — and it helps you feel less freaked out or impotent — and you give it to five of your friends, and they pass it on. That’s the way truth and hope spread — it’s quantum. Stories are what save us. They always have been.

Stories are what save us.

RR: I’m interested in how the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves shape our lives, and I think that is one of the themes of your collection. So let me get really philosophical with you: how much do you think we’re in control of our own narratives/our lives?

AL: In my own case, I began making up stories about myself to explain why my parents were so unhappy with each other. In the story children tell, it must be them. They must be causing some of the unhappiness between their parents, because otherwise you have zero control. And so you start to tell yourself a story about how you’re defective or annoying. And that explains it. That explains that the chill in the air at dining room table, and that gives you control, because then you can try to fix yourself — which is not possible — or you can try to be less annoying and more adorable and charming. So we develop the skills of people pleasing.

If you grew up in an alcoholic or addictive family or a family with mental illness, just about the first thing you agree to is not to see what’s going on. If you see it, it makes them so mad, and they tell you you’re imagining things. So you need to stop seeing what’s there. Part of the great healing of writing is to realize that what you see is going on, and what you see is true, and you’re a reliable narrator.

I think as powerless, really frightened little children — as most of the people I’m close to were, holding your breath and walking on eggshells, hoping dad isn’t drunk or that mom pulls it together and doesn’t have to go back to the doctor — we lose the most essential trust we can have, which is in ourselves. Writing — which takes tremendous trust and faking it, shitty first drafts, and rewrites and asking for way more help than your parents or the culture ever told you you deserved — is the way. Asking for help is the way we develop trust in ourselves. Writing really terrible first drafts is how we develop trust in our writing.

RR: Talk to me about your techniques for writing humor, especially when you’re writing about difficult subjects.

AL: I seem to trust that somehow my voice is helpful or comforting to a number of readers. My first novel was called Hard Laughter. It came out when I was 26. It was about my father’s brain cancer. We knew he wasn’t going to recover from it because it was a metastasized melanoma. I wrote the novel as a kind of love letter to my father, knowing he wasn’t going to live. He actually lived long enough to read it and to know that it was going to be published by Viking, so it was kind of a miracle. It was called Hard Laughter because it’s really, really hard to laugh when you feel that it’s like the end of the world, which it was. I was young. I was 23 when my dad got sick. It’s the same feeling as when we got the climate news on Monday. It just feels like the end of the world, and it’s really hard to laugh.

You can do the fake laugh so that people won’t think you’re a buzzkill, or you can stay in the truth and in the sharing of the bad news, the brain cancer or the climate change, and you and your friends will just start laughing. There’s a lot of laughter in doom. I’ve always said laughter is carbonated holiness, and it really is a spiritual experience when we can laugh. It breaks our shells, and then stuff gets in, breath gets in, light gets in, nourishment gets in.

You discover really by 20 what resonates for you, what you long to come upon, what voice, what material, what tone. You love, say, historical novels, you just get so lost in them. And in reading and in writing, that’s how we get found, by getting lost in the story.

I’ve always said to my writing students: Write what you’d like to come upon.

And that’s what I have always done. When I wrote Hard Laughter in the 70s, there was not a word on a family coming through cancer that wasn’t a tragedy. For our family it was a tragedy, but also we laughed, and we found a lot of comfort in sticking together. And I thought, God, I’d love to come upon something like that, a real family, not a Hallmark family.

So write what you’d like to come upon, because finding what you want to come upon is like finding your soul.

RR: One of the things that strikes me most about your writing is that you can make the intangible tangible. How do you write about abstract concepts we cannot see?

AL: If you showed me a paragraph you love that I’ve written, I can tell you the first draft looked like I was trying too hard, or it was full of clichés.

There’s a lot in Almost Everything about being able to give up identities, like the identity as the family flight attendant or the family diplomat. That’s really hard to write about without it seeming like a self-help book.

I always have a pen. That’s the secret to my writing. I always have a pen with me. All my blue jeans have a little ink stain in the back pocket. If I can’t find paper, I can write on my arms and hands and transcribe it later.

I might say to my partner, Neal, ‘Talk to me about how you’ve jiggled free from some of those early identities.’ He’ll start talking, and all of a sudden, I’ll go, ‘Don’t say anymore!’ Then I’ll scribble that down.

But I write lots and lots of drafts. Anything you like began as a shitty first draft. And the same thing can be said for any other writer you love. I hate criticism, hate it, but I’m so grateful for good feedback. I’m so grateful for editors, copy editors, and friends.

When I was coming up as a writer in the 70s and 80s before we had computers, when Correcto Tape was a huge breakthrough or Liquid Paper, people would talk about putting your work through the typewriter again. That meant you pushed back your sleeves, and you wrote one more draft, and you got really tough with yourself. You went through it paragraph by paragraph, sentence by sentence. A lot of it you could leave, but some of it you couldn’t — just like real life.

RR: What stories have you been reading and sharing? What is giving you hope?

AL: I loved Dopesick by Beth Macy. It reads like fiction in the sense that she’s such a good writer. It’s about the addicts and the parents and the towns affected by the opioid epidemic. But it’s also about the pharmaceutical companies’ complacency in creating the epidemic and the solutions that are working here and there, which is all we ever have.

I just read a book I really loved, a novel called The Devoted by Blair Hurley. I love books on faith, and this is from a Buddhist perspective. It’s about a very committed young woman going up the ranks at a zendo in Boston. It has everything I like to read about: devastation and finding your way home. It’s about the crumbs that lead us back to the past. She’s the kind of writer — I know you know this feeling — that makes you so jealous that you know you can’t write like that, you can’t think of those images, but you’re so grateful to read them. Because they’re mesmerizing, and they give you hope. Great writing gives you hope.