Books & Culture

Are We Alone?

VanderMeer presented a version of this essay as the keynote speech for the Arthur C. Clarke Center for the Human Imagination’s “Are We Alone?” conference in early June of this year.

1. The Meaning of A Question

Are we alone? There are so many possible ways to begin to answer this question, confirmed by even a quick glance at the long, comprehensive wiki entry for “Fermi Paradox.” The back-story on the “Fermi Paradox” — why haven’t we encountered aliens yet — reads like science fiction. Certainly, the scenarios it sets out are all consigned to the realm of storytelling for now and even the most logical speculation may turn out to be wildly inaccurate. For this reason the science of alien contact and the fiction of it dovetail in interesting ways and explains why speculation on the subject is sometimes more powerful and useful than empirical approaches. How and why speculation is sometimes more logical than science is also interesting, as the question begins to turn to issues of human interpretation and bias.

Delving into the topic of alien life through the lens of science fiction makes more sense than in perhaps any other field of scientific inquiry. There are hundreds of stories and novels devoted to this question — and some of the most well-known “answers” come to us from one of the most famous SF writers of all time, Arthur C. Clarke. Clarke gave us several glimpses into possible alien intelligence in his work, including The Sentinel, which inspired Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001. That might seem to be an obvious jumping off point for the subject, but I find a lesser-known story by Clarke even more relevant because it is more complex and more human.

Clarke’s “The Star” (1955) tells of a spaceship expedition that encounters the ruins of an extinct alien civilization whose star supernovaed. In the twist at the end, the expedition discovers that the light from the supernova reached Earth around zero A.D., manifesting as the star seen over Bethlehem in the Christian Bible.

Clarke’s story is powerful not just because of the juxtaposition of life and death, death and rebirth, but also because it mercilessly interrogates human ideas of meaning about the universe. Some readers take the story as a critique of organized religion, but it is more complex and empathetic than that. The story is very much about the human need to create story out of what we observe around us — to, in any context and by whatever means, make sense of the unknown or the unknowable. Creating a fiction out of reality.

It’s telling that the priest narrator points out “my order has long been famous for its scientific works” but that the scientists on board the spaceship dismiss the priest despite these bona fides. “It amused them to have a Jesuit as chief astrophysicist[; they] could never get over it.” Whether intended by Clarke or not, there’s an indictment in that dismissal, that lack of an attempt to understand another’s point of view. That dismissal is especially ironic given that the need to create narrative and purpose is prevalent even in so-called empirical scientific endeavors.

“The Star” also subverts a related science-fictional theme: the desire to reach beyond, to go farther, to experience more: “No other survey ship has been so far from Earth; we are at the very frontiers of the explored universe.” The expedition in “The Star” and their space craft could be said to be the physicality of a thought expressed first in the imagination and then made manifest. Creating reality out of fiction. Sometimes this thought first occurs in the form of a simple question. Sometimes the answer is perilous. Sometimes the question answered is not the question you asked. Are we alone?

Who are “we” and thus who are “they”? Which “we” and which “they”? Are we not alone if we find microorganisms on Mars? Or is that somehow anticlimactic. Are we not alone if we find a random mammal contentedly munching on some form of vegetation on a planet orbiting a distant star? Or, are we only not alone if we find some form of life we deem truly intelligent?

Or, must we find intelligence that’s “relatable” in the sense that we as humans recognize in this intelligent life-form traits we ourselves possess? “Even if they had not been so disturbingly human…we could not have helped admiring them,” the priest in “The Star” writes. At what point is the switch flipped from “alone” to “not alone”? Would a satisfactory answer differ for the alien we might someday meet? Would the very idea of the question mean something radically different?

Clearly, for human beings, the question wasn’t answered at the point at which we realized the sky was full of stars and that they did not revolve around the Earth. The question at that point was complicated by the fact that those who did not want the answer killed or imprisoned those who began to suggest its outline. Nor was the question answered, nor did it become a different question, when we trained powerful telescopes on those stars and began to discover the planets that orbit them.

The hidden insatiability at the heart of the question speaks to a need for meaning through connection, which made me think immediately “are we just trying to avoid some other question?” And what would replace the question if we ever answered it in the affirmative? Would that answer be sufficient?

If I’m not sure, it’s because I’m not sure how de-linked the question is from rationalizations to continue the Western drive for limitless expansion. How much in locked step our need to find other life marches beside some other impulse. In tackling the issue in “Colonize Mars? Not until we learn some lessons here on earth,” an essay published at Fusion.net, Dr. Danielle N. Lee asks the question, “Is it right to think about the galaxy as a playground that is ours for the taking?”

She quotes NASA Space Communicator and space policy analyst Dr. Linda Billings, who notes the language used by astrophysicists of “frontier pioneering, continual progress, manifest destiny, free enterprise, rugged individualism, and a right to a life without limits.” As Lee puts it, “Within astrophysics circles, the idea that it is our right and imperative to conquer other planets is presented as natural.”

I would hope that “Are we alone?” isn’t just the booster rocket for Manifest Destiny transformed. I’d hope that it’s also, or instead, an expression of a genuine empathy and desire for discovery. A genuine reaching out. Yet even empathy, like a telescope, can be directed on one place and ignore another entirely. And discovery, for human beings, has rarely meant anything as selfless as quenching a desire for contact and for pure knowledge. The famous “sense of wonder” in science fiction has often been achieved by ignoring flawed assumptions or simplifications embedded in the foundations of the story. In thinking of first contact, we sometimes forget the tragedy and genocide of first contact between different groups of humans on Earth — usually at the expense of indigenous populations.

A question, then, that makes us look outward, can carry with it perilous assumptions about our place in the universe and our place on Earth.

2. Aliens From Beyond

This looking out, the searching of the wider expanse beyond our own planet, whether fact-born or fiction-born, is in some sense equally speculative — the idea of a confluence between science and fiction interesting, too, because it has historical underpinnings. Early scientific papers in the West by the likes of Francis Bacon and Johannes Kepler took the form of “contes philosophiques” or “philosophical tales,” in which the fictional framework of an imaginary or dream journey surrounded some sort of scientific speculation. In the late 1800s, some scientists even presented their findings in the form of poetry.

If the boundary between fact and fiction is at times porous — if its delivery systems sometimes resemble each other — it’s certainly so in talking about extraterrestrial life. In part for this reason, when we finally do encounter intelligent alien life it’s likely that most or all of our fictional and scientific speculation will be rendered obsolete. That everything you’ve read on the subject will be like the supposed canals on Mars in fiction from days of yore or the jetpack future of the 1950s we were all promised. Making this even more certain is the constant dilemma of the human condition, which is its subjectivity, so that even a seemingly simple concept like “scientific accuracy” can become unmoored in unexpected ways. Often, in looking outward, we are receiving back what we want to perceive. In areas like physics, the New York Times reports, there’s even a clash between empiricists and those who are willing to accept “sufficiently elegant and explanatory” theories.

Thus, any methodology applied to the subject of aliens must factor in the limitations of the human gaze — which is often illogical and unaware of its own bias. Part of the problem is the obvious one: we have only five senses (so far — that may change) and no matter how we augment those senses with hard tech, it is still difficult for our imaginations to extrapolate beyond those senses. We see this daily in how we continue to behave in self-destructive ways, stand behind terrible policies, because some of the consequences are hidden from our direct view or occur in a realm invisible to us. Nor is this lack a problem for the layperson only. Dedicated scientists experience it as well.

Our brains also constantly work to convert the world into metaphors and similes — into comparisons that help us to navigate our way through life. Some of this is instinctual, some specific to culture, as explored in Hofstadter & Sander’s fascinating book Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking. In trying to reach beyond, our limitation is that if we’re not diligent and on guard our conceptualizations default to the wrong things.

A recent example of this limitation comes directly from SETI — in a New York Times op-ed piece by Seth Shostak, director for the Center of SETI research at the SETI Institute. In talking about the risk of proactively sending out signals that might be picked up by a hostile presence, he speculates about how aliens might perceive the injustices we’ve perpetrated on one another.

Personally, I think this concern is overwrought. Any society that can pick up our radio messages will be at a level of development at least centuries beyond our own. They would be no more incensed by our bad behavior than historians who learned that Babylonians attacked one another with spears. It seems naïve to imagine that, by shielding aliens from the less flattering aspects of humanity, we would somehow lessen any incentive to do us harm.

I find this comparison disappointing at best. “No more incensed…than historians who learned that Babylonians attacked one another with spears.” What belief is Shostak invoking? What leap of faith? Faith does not have to include a star in the heavens. Because the star is a symbol, we will always supply the star in some form.

Perhaps Shostak is trying to be relatable for a general audience. But even so, if the director of SETI can conceptualize aliens in such an unimaginative way, it exposes a possible flaw at the heart of our endeavors because such comparisons are meaningless — the words have no actual meaning at the coordinates they have been given.

It’s important not to over-deify scientists and scientific organizations in general, especially in areas that require rather more speculation than others — especially since scientists need to have the freedom to fall on their faces like everybody else. So I say with not too much judgment that the same day I read the SETI editorial, I also read an article about a professor from the University of Barcelona who thought about aliens in the context of Bayesian Statistics and some generalizations about Earth that probably needed more rigorous interdisciplinary analysis. His conclusion? That most likely “Aliens Will Be Bear-Sized Because: Math,” and, specifically, a planet of about 50-million intelligent bear-sized aliens.

With rather more judgment, I can tell you that the same week I listened to Freeman Dyson on NPR saying that global warming is not a big problem, as well as other ignorant things. I also read an article on how gender bias among scientists led to the assumption that the planet represented by the human egg played a passive role in relation to the expedition known as sperm — an assumption now known to be wrong.

If I self-identify as an absurdist in thinking about this weird world of ours, it is to remind myself that, again, life often only forms a coherent narrative because we impose that narrative upon it. If I want to always be aware of the irrational behavior of human beings and of human institutions, it is to, as a novelist, not operate from the same old defaults.

All of this has a point — leading back to SETI, for example. The constraint was put on the question “Are we alone?” by SETI, in its decision to monitor radio waves, and focus mostly on a certain range of radio waves. A default assumption was made because it had to be made, because sometimes science is just a best guess. But are alien super civilizations really “absent from 100,000 nearby galaxies” as reported in a Scientific American article or are we just too primitive or bound by our own stance and perspective to see them? One imagines some alien culture with its own version of SETI based on a completely different set of assumptions.

What, then, does it really mean to be alone or not alone? If you are alone, are you by definition lonely — with the yearning that implies? What does yearning — desire — do to warp the results of an inquiry? And wouldn’t it be reasonable to assume that many forms of alien intelligent life out in the cosmos do not suffer a similar angst about “being alone”? And is our angst about it healthy or somewhat unhealthy?

In such a context, where so much is speculative anyway, I’m reminded of the mind-blowing stories of R.A. Lafferty, which do not strive for realism but in their surreal approach are perhaps more useful than “hard science fiction” in expanding possibilities about alien life. In one of Lafferty’s tales, “Nine Hundred Grandmothers,” an expedition discovers that the intelligent aliens on the planet they’re exploring are matriarchal, and that every female member of this alien species is still alive. In a remarkable scene, the protagonist passes through ever-smaller subterranean caverns to meet the original alien matriarch. Whether this is a plausible real-world scenario, it definitely trumps and is more useful than a prediction of “bear-sized” aliens or comparisons to the ancient Babylonians.

In another Lafferty story, “Thieving Bear Planet,” the aliens are portrayed as capricious and erratic because their ultimate motivations cannot be grokked by human beings. The human expedition encounters weird gaps in time, small replicas of themselves, and hauntings that only make sense as part of an alien methodology. Lafferty’s genius is to show only glimpses of that methodology, thus giving a true sense of what alien contact might be like.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic “Vaster Than Empires, and More Slow” extrapolates in a different direction, telling the story of an expedition to a distant planet where sentience takes the form of plant life. Only one member of the expedition recognizes this sentience because to the others the context in which it exists is faulty, not the usual, forms a different pattern.

Similarly, in Dmitri Bilenkin’s “Crossing of the Paths,” a 1970s story from the Soviet Union, the divide between the alien and human is extreme. Bilenkin’s story describes an encounter on a distant planet between a human expedition in a vehicle sent out from a space ship and an alien species known as the mangr. The mangr looks like a huge thicket of bushes across a hillside. In fact, it’s an intelligent collective and nomadic to avoid the giant electrical storms that plague the landscape. The humans in their crawler try to drive right through the mangr but become trapped because of a series of mistakes based on the standard assumptions one might make about the Earth version of a thicket. During what follows, the crew never fully figures out that they’ve encountered intelligent alien life because the aims of the humans and of the aliens are so different. Nor do the aliens recognize that they’ve encountered intelligent life, either.

Nor, in their alien context, would they care if they did. Each reacts as to their nature and their precepts and each is thus unaware of one another.

A circle looks at a square and sees a badly made circle.

3. The Aliens That Live Among Us

Recognition, then, is an essential step in asking the question “Are we alone?” Recognition of intent, perhaps. Recognition of something not ourselves, not acting like ourselves, that yet has some form of sentience. But if our own recognition of intelligence is incomplete, how do we know that “we” constitute the kind of intelligence that another intelligence might recognize? In other words, do we fulfill the very requirements we ask of “others”?

Frankly, I am not sure we have proven we can recognize intelligence when we encounter it. I would argue that for the longest time we have denied that intelligence exists all around us, in the animal world. Almost all of our cultures, societies, our national identities, and our day-to-day habits tell us that this is our default position. It may be true that some of us exist more in harmony with our surroundings and leave less of a “mess” for the Earth to deal with, but that’s a different issue.

Only in recent campaigns to grant personhood to apes, dolphins, and other species, do we see the beginning of the recognition that we have never been alone. Certain laws begin to acknowledge interdependence too. In 2010, Bolivia passed a law establishing the Rights of Mother Earth and acknowledged the “dynamic living system formed by the indivisible community of all life systems and living beings whom are interrelated, interdependent, and complementary.” A law passed in New Zealand this year which declared animals “sentient,” taking sentience to mean able to “experience positive and negative emotions.” (This is rather less than what’s needed, but still a step toward recognition.)

Recognition has been difficult for a number of reasons — our limited senses and very particular ways of categorizing the world are further stymied by encounters with very different types of life that surround us. We’re only now beginning to realize that not all sharks are solitary, for example. Some sharks have complex social networks, which hints at a sophistication we’ve longed denied them. “Even” fish, which we tend to see as inert objects, incapable of feeling pain, we now know interact in sophisticated ways. According to an article in Nature titled “Inside the cunning, caring and greedy minds of fish,” they can, among other things, “cooperate, cheat, and punish.” These findings are changing how we view brain evolution.

Philosopher Timothy Morton in his essay “Human Thought at Earth Magnitude” published earlier this year in the Sonic Acts Geologic Imagination conference book even makes a compelling argument for the thought-experiment of mapping similarities between the imagination of bees and the human imagination — that animals like bees may make more decisions than we think while at the same time we humans put too much of what we do in the category of requiring conscious thought. Given confirmation bias we can no longer be certain aspects of the human imagination are not actually a series of set operating protocols and automated systems.

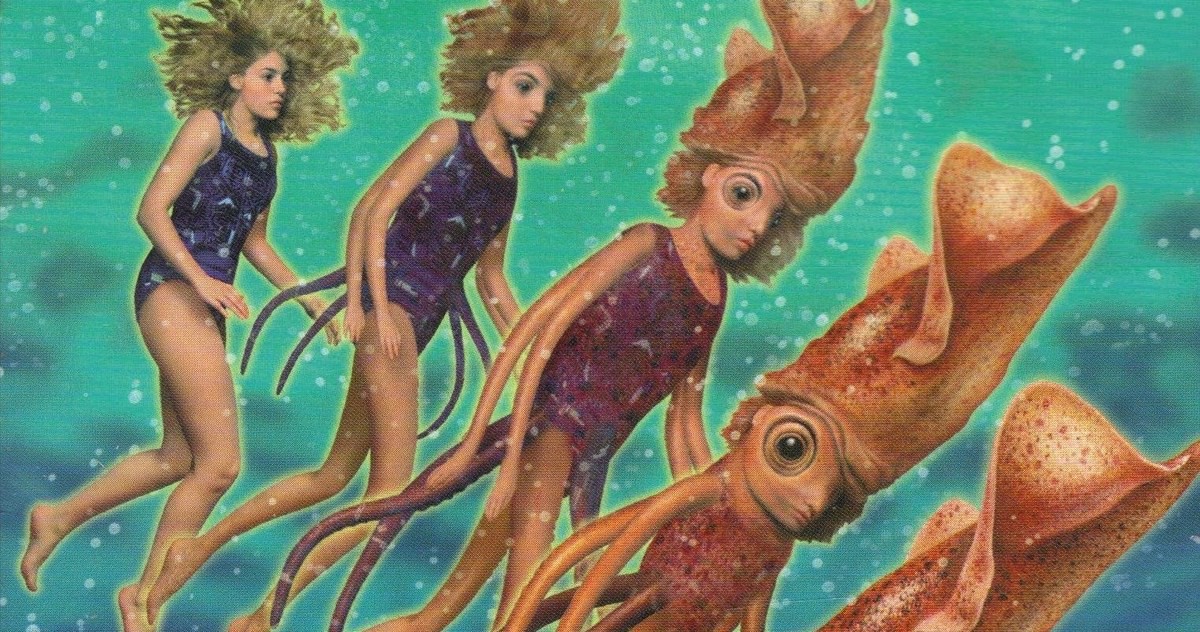

That may seem like a radical idea, and perhaps hard for some to believe. But it’s harder to discount examples of “alien” higher-order intelligence on our planet. Sy Montgomery’s recent The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the Wonder of Consciousness provides anecdotal evidence of not just octopus smarts, but also evidence of how different that intelligence is. An animal that sees through its skin and has a brain that may in part reside in its tentacles will not think like us — would never think like us. Neither would an alien from outer space that evolved in a similar way.

How horrific would it be if humankind reached the stars, landed on a planet, and wound up eating sentient life-forms without realizing it? What if aliens arriving on Earth were so different from us they couldn’t recognize our intelligence and only saw us as succulent protein?

But there’s another reason we haven’t recognized these aliens amongst us. Today’s world contains so many examples, on a daily basis, of casual cruelty and thoughtlessness toward animals codified as practicality or reasonable behavior or even, in the worst examples, a twisted kind of empathy regarding aspects of the environment and the animals that populate that environment. These unexamined assumptions become agitprop for status quo.

This agitprop is a kind of a kind of slurry or run-off from our online experience, which is not only becoming close to the totality of the Western experience, but is full of animals pushing slogans of universal truth or some humorous saying. Wise owls, “otter nonsense,” smiling dolphins. Because we love animals. We usually love them as long as they’re funny or cute or in some other way reduced down to a meme. We breathe life into them using carelessly corrosive received ideas, each iteration farther from any kind of true seeing. If sharks looked friendly to us, like dolphins, we would probably view them at least a little differently. (In a context in which dolphins are known to be stone-cold bastards.)

Still worse are images like a popular “cute” one of an otter in a glass cage. Holes in the cage allow people who come to the zoo to shake hands with the otter. This image is shared and re-shared with seemingly little realization that if the image showed a human being in a glass cage, trained to shake hands with visitors, no one would be calling it “cute.” Perhaps that view — and John Crowley’s recent hoary rumination that animals can’t foresee their own deaths — would be revisited after reading “Aid to a Declining Matriarch in the Giant Otter,” with its useful thoughts on otter cooperation and “human exceptionalism.” Or perhaps an otter isn’t the right meme to flip the right switches in the human brain — perhaps you need to substitute an orca in a tank instead. (Even the usually reliable Ted Chiang in trying to create a parrot’s point of view ultimately gives humanity a pass in a way that makes it clear he’s trapped in the human gaze.)

Rejecting false information and finding a new path is incredibly relevant to human survival because our current crises are in part fueled by mindsets that see animals and our environment as disposable. But it is also relevant to our search for alien life, and our expectations and assumptions about that life. Because ultimately we must come to terms with the fact that other forms of intelligence always lived among us and that we ignored these forms and have also terribly abused them. Because this may help us to understand more clearly that ideas like Manifest Destiny that still permeate our society, sublimated in a devotion to unsustainable and endless growth and, yes, a reaching for the stars, also pertain to how we might treat aliens from far-distant places.

To become more, we must become less. To answer the question “Are we alone?” we must be receptive enough and humble enough to actually see what is around us on this planet. We must learn to live within limits.

4. Tech and AI

Perhaps, too, if we had paid more attention to the localized answer to “Are we alone?” we would already have cities that take as inspiration the complex ecosystems found at the top of redwoods. Maybe we’d be able to see that a smart phone is fairly crude next to the ways plants and trees communicate with one another through fungal thoroughfares, that the symbiotic relationship between the albatross and the sunfish reveals a startling and unexpected complexity.

In such a context, I don’t think I’m a luddite to wonder if we’re not often using primitive modern tech like our phones and even GoogleGlass to build an inaccurate, blinkered prism of the world around us. One that walls out not being alone with shiny reflective surfaces and fragmentation of our attention spans. This isn’t at all to say that modern technology can’t engage in a meaningful way with these issues. Modern tech is incredibly useful to a wide variety of scientists — and in the area of renewable energy may be human civilization’s last hope. In many fields, specialists have begun to invest our human world with products that mimic the best of animal efficiencies and complexities, regardless of the issue of consciousness. In terms of space travel, technology developed by NASA has proven very useful to those of us on Earth, as well.

But much of our every-day tech, the systems that shape our thoughts and thus our consciousness, comes with an underlying assumption: that it is logical and forward-thinking. And if that is true, surely the creators of seamless tech are themselves logical and forward-thinking. If you want another view, a very dystopian one, read the article “Come With Us If You Want To Live: Among the Apocalyptic Libertarians of Silicon Valley” by Sam Frank in the January 2015 issue of Harper’s Magazine. There you will find manifestations of the absurd that will make you wonder what an intelligent alien from another planet would think of our intelligence — from a commitment to cryogenics to things far more outlandish, disguised as part of “the new enlightenment.” You will also find odd statements that include the assertion that AI is much more complicated than natural ecosystems. Yet as far as I know, human beings have never created a complex natural ecosystem from scratch.

In talking about this issue on social media, Skyler Nelson, who works for an AI company, told me he sees this point of view among tech elites as a barrier to advances in his field. I quote him at length because it shows that people are beginning to get the message.

The funny thing is that we’ll go out of our way to attribute agency to things — we’ll ascribe a purpose to any movement we think we can discern a pattern in (and we’re overzealous pattern recognizers — we’ll infamously become convinced of patterns where none exist). But we have this over-specific anthropomorphic concept of intelligence that we’re extremely hesitant to apply. We don’t recognize other forms of intelligent behavior in animals and we’re unfortunately hesitant to even see intelligence in the behavior of people who differ from us significantly.

And the really funny thing is of course that the sort of logical, sequential reasoning that many of us take to be the hallmark feature of intelligence is something that we humans rarely actually do — there’s an increasing amount of evidence from the neurosciences that most of our decision-making processes occur at the instinctual level and are sort of retroactively justified by reasoning processes when necessary.

What is intelligence? If we’re still figuring that out — and if science eventually shortens the distance between, say, a bee and a human — then it’s likely our quest to answer the question “Are we alone?” will change radically in the next century.

All of this hopefully chips away at the fallacy that we have already discovered everything about this world we live on, which gives most of us the idea that somehow we have more positive control over our environment than we do.

All of this would get us closer to being better prepared if, at some point in the future, the question of “Are we alone?” is answered in the affirmative by visitors from some distant planet.

All of this makes less likely that when that day occurs we bring with us all the old baggage, all the old assumptions. All the useless things we don’t need, and haven’t needed for a long time.

5. The Next Step

In the end, to answer the question “Are we alone?” we cannot look outward without a better awareness of our surroundings on Earth — and without looking inward. To be complex in our thinking but clear in our expression. To not reduce down to binaries or generalities but not get lost in the details, either. What will we encounter out there but ecosystems? What will life be but different?

To think in positive terms — about our human systems, about our tech — perhaps re-purposings can help us too. Imagine what could be accomplished in seeing the miraculous in the every-day if someone invested in a virtual reality experience that showed us the hidden underpinnings of the world, the world we have so much trouble seeing.

The process would start with biologists and chemists and environmental scientists and a host of other experts in various fields coming to your neighborhood, to pre-map the world beyond the world. Afterwards, you’d put on the device and walk down your street. Everything would be identical to what you’d see with your own eyes…except you’d also see the chemical signals in the air from beetles and plants, pheromone trails laid down by ants, and every other bit of the natural world’s communications invisible to our primitive five senses. You’d also see every trace of pesticide and run-off and carcinogens and other human-made intercession on the landscape. It would be overwhelming at first.

But once you got used to it, more advanced settings might be possible. You’d look at the ground and it’d open up its layers, past topsoil and earthworms down into the deeper epidermis, so to speak, until you’re overcoming a sense of vertigo, because even though you’re standing right there, not falling at all, below you everything is revealing itself to you super-fast. And maybe then, while still staring at the ground, you’d have an option to regress to simulations of the same spot five years, ten years, fifty years, two hundred years ago…until when you look up again there’s no street at all and you’re in the middle of a forest and there are more birds and animals than you could ever imagine because you’ve never seen that many in one place. You’ve never even seen this many old-growth trees before. You’ve never known that the world was once like this except in the abstract.

You’re, in fact, standing on an alien planet. And once you got used to that, maybe then…only then…you’d be able to “play the game” at a level in which you inhabit the consciousness of an animal — something less advanced at first, like a tortoise or squirrel, and then work your way up to something “fairly” intelligent like a wild boar or a raccoon.

And once you’d worked your way “up” to human or sideways to human or down to human…whatever that looks like…then and only then would you be allowed to look at the stars, to imagine the cosmos, and to encounter the alien life that might exist there.

If enough people play the “game” right and understand what it means, you, your children, your grandchildren, and your great grandchildren live long lives and everybody continues to have things like electricity, which makes using virtual devices a lot easier.

***

In Clarke’s “The Star,” the expedition discovers the alien ruins on a planet at the edge of their solar system, farthest from the supernova’s impact. These aliens, too, had reached out for contact, building a Vault meant to contain “everything they wished to preserve, all the fruit of their genius.” The purpose is to preserve these things for anyone who might arrive long after the aliens are dead. “Would we have done as well,” Clarke’s narrator muses, “or would we have been too lost in our misery to give thought to a future we could never see or share?”

Earth faces not an impending supernova but instead a slow apocalypse that is beginning to move faster and faster. Are we alone? We will be soon, if we don’t change our ways. Despite pockets of enlightenment, we often act as if we’re settlers on an alien planet. But we don’t live on an alien planet. We have no home world to go back to if things fail here. We were born here, and we will die here, no matter how many new planets astronomers discover. This is the place we must pay attention to, and re-learn how to live in — to find a good answer to the question of what we contribute to the global biosphere.

In the end, then, we are still on an expedition in the middle of the unknown — on a wondrous and complex planet that we are only beginning to understand — that manifests in beautifully interconnected ways even in a patch of weeds springing out from a piece of cracked pavement. And we are, as ever, in existence in the moment and no more. This is where we’ve always been even if we haven’t always realized it. We can never totally discard the human gaze because we are human, but we can imagine our way past it.

Fully living within and thinking deeply about a question like “Are we alone?” is an important part of that experience.

In altered form, two paragraphs about animals in this essay also appear in “The Slow Apocalypse and Fiction.” The ruminations on a virtual reality experiment took nascent form on the author’s personal blog.

A short version of this essay focusing on part 2 appeared on the Guardian website earlier this year.