Interviews

Art Is Always Political in an Authoritarian State

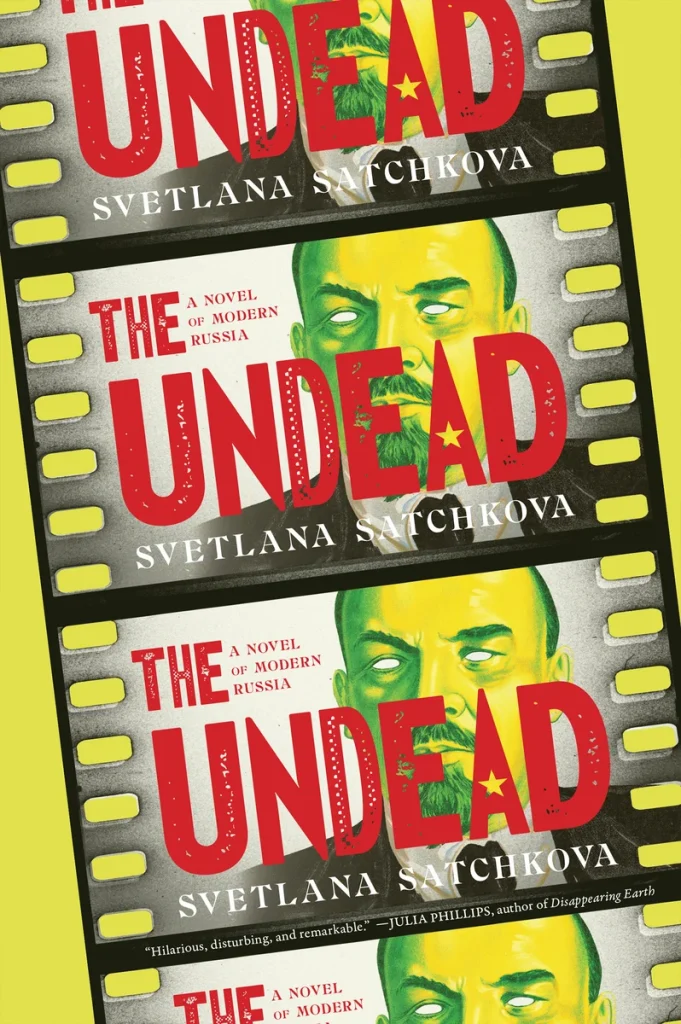

Svetlana Satchkova’s “The Undead” contemplates artistic responsibility, state censorship, and the risks of being an artist in Russia

While many of us watch with dread as American society is rocked by menacing politics, New York-based author Svetlana Satchkova has already lived through the experience of her country becoming more authoritarian. Her debut English-language novel, The Undead, grapples with the fear she experienced as a cultural journalist and novelist in Putin’s Moscow, before moving to the U.S. Her protagonist, Maya, is a 30-something debut film director making a lo-fi movie about ghouls led by an undead Lenin. As an artist, Maya believes it’s important to stay out of politics. The problem is, politics doesn’t plan to stay out of her life. After all, just because you shut your eyes doesn’t mean the ghouls won’t get you.

As a product of the Soviet Union myself, I spent many years staying out of politics until I wrote a novel exploring the repercussions of societal fear. Being apolitical was part of my conditioning (free elections aren’t really a thing in totalitarian states). Upon immigrating to the U.S., I was surprised to discover that here most people voted, went to protests, and generally believed their voice mattered. Americans felt neither scared nor resigned to their fate.

Satchkova’s The Undead portrays a society where fear creeps in until it becomes an indelible part of ordinary life and work decisions. It’s not a darkly intense novel: There is the joy of art-making, friendship, drama, romantic entanglements, and even a bathroom sex scene on a film set. But, like in a classy horror flick, the thrilling undercurrent of dread is there all along. With real events underpinning the fictional plot, The Undead brings to life what we don’t like to think about—that the comfortable reality we know and like may one day betray us.

Sasha Vasilyuk: You were working as a successful journalist for publications like Glamour and Vogue in Russia, interviewing everyone from Helen Mirren to Tommy Hilfiger. What made you want to leave in 2016?

Svetlana Satchkova: My last place of employment was Russian Condé Nast, where I first worked as Deputy Editor in Chief at Allure and later as Features Director at Glamour. I mostly covered culture, and it was a fabulous life—I went to movie premieres, film festivals, parties, and traveled all over the world to interview celebrities like Alicia Keys, Antonio Banderas, Gwyneth Paltrow, et cetera.

But the atmosphere was getting worse. Repressions were increasing as Putin consolidated his power. As a journalist, I made a conscious choice not to write about politics, economics, or social issues because it was dangerous. Many journalists were killed, poisoned, driven out of the country, or imprisoned. I always wanted to cover those topics, but I chose not to because I was a single mom with no relatives in Russia, and I worried about what would happen to my son if I were arrested. It was scary to live in Russia.

SV: Your protagonist Maya doesn’t follow politics. How about you?

SS: I was following politics, but many of my friends weren’t. That’s where the idea for my novel came from. They were successful professionals who couldn’t understand what I meant when I said I didn’t see how I could keep living under a repressive regime. They simply didn’t notice what was happening. And I couldn’t tell whether they were willfully ignoring it or just uninterested in anything outside our bubble of great restaurants, exhibitions, and theater productions. They said, “Our life is great—what else do you need?” And I said, “I need to feel secure in my own country. I need the police to protect me rather than threaten my existence. I need to be able to say what I think.” We kept running into this conflict, and that’s what I wanted to explore when I started writing The Undead: the different coping strategies people develop when living in an autocratic state.

SV: How did you draw on your experience as a journalist for The Undead?

I made a conscious choice not to write about politics because I worried about what would happen to my son if I were arrested.

SS: I did a lot of reporting on the Russian film industry, interviewing most of its major actors and directors. (Readers familiar with Russian pop culture will recognize some of them in my novel, though their portrayals aren’t exactly flattering—which is why I changed their names.) Over the years, I spent time on countless film sets, so I know how the industry operates from the inside. What many people don’t realize is that the Russian film industry is funded almost entirely by the state, through various structures that collect government money and channel it into productions. In a way, Russia simply inherited this model from the Soviet Union, where everything was state-owned.

SV: Is that why you chose the film industry as the novel’s milieu?

SS: I just knew the film industry very well and many of my friends came from it. The story of Maya is taken in part from the experience of a close friend. She was a debut film director who was considered a genius in her graduate program. She signed with a producer, shot her first movie, but then the producer began stalling on the postproduction funding. The film never came out, and that became the tragedy of her life: She never wrote or directed anything again. Eventually, she became a housewife. I wanted to explore how creative people deal with failure, and why some of them can’t find it in themselves to move past it and keep going. But as I was writing, I kept thinking about Navalny, Putin, and the war in Ukraine, and politics worked its way into the story. I couldn’t just write about a small person facing a personal tragedy in times like these. You could almost say the novel had to become political. And I think it’s stronger because of that.

SV: Maya isn’t aware of everything happening around her until it’s too late. How much do you think art matters against power?

SS: It matters to me because my whole life revolves around the arts. But I guess it doesn’t matter so much to people who aren’t interested in them. Maybe film, because it’s so accessible to audiences around the world, can really influence people.

In Russia, nothing can challenge authoritarian power, neither literature nor film. But in a different context, living under democracy, some change can be affected by a work of art, especially if it becomes very popular.

SV: Should art be political?

SS: I think it should. Especially in times like these, it feels important to write about what’s happening, because everything around us is political. And while I published three novels in Russia, I didn’t touch on political topics for the same reason I didn’t cover politics as a journalist: I was too afraid. But once I came here, my fiction naturally became political, simply because it’s what I’m constantly thinking about now.

SV: Fear plays a major role both in your life and in the novel. Maya is making a horror movie and is also afraid of her stalker ex-boyfriend. What does fear do to artists and art-making?

I couldn’t just write about a small person facing a personal tragedy in times like these.

SS: There’s an irony in what happens to Maya: She’s afraid of so many things in her personal life, yet she isn’t afraid of what she really should fear—the state. Under a regime like Putin’s, there is no way to play it safe. Even if you keep a low profile, even if you never speak out, you can still become a target. Maya’s story reflects my own fear of what might have happened to me if I had stayed in Russia, even while making “safe” art.

SV: How did the arrest and sentencing of the Russian poet and playwright Zhenya Berkovich and theater director Svetlana Petriychuk in 2024 affect the writing of your book?

SS: Berkovich and Petriychuk staged a very successful anti-terrorist play about Russian women who married ISIS fighters and were abused. The message was clear: Don’t do this. But everything was turned upside down when prosecutors later claimed the play promoted terrorism. After the invasion of Ukraine, Zhenya began posting anti-war poems on Facebook, and I remember almost pleading with her in my mind: What are you doing? Aren’t you afraid? They’re going to send you to jail. And that’s exactly what happened.

It’s obvious to me that this was the real reason for the prosecution of Zhenya and Svetlana, and that the play, which had received government awards, was just a pretext. I followed the trial closely, and it was completely absurd. Everyone in the courtroom knew they were saying gibberish, but the machine kept going. The women are now in prison, each sentenced to six years. The grotesqueness of it made me think: I have to use this. The trial in my novel follows theirs.

SV: After publishing three novels in Russia, you deliberately stopped writing in Russian, a decision that has been hard and controversial for many Russian writers who now live abroad (not to mention American authors who continue to sell book rights in Russia). Can you talk about your reasoning?

SS: To be clear, no one has offered me a contract in Russia in the last four years, and the journalism I used to do was for independent Russian publications, most of which shut down after the invasion. So the fact that I don’t write in Russian anymore happened organically. But if I were offered a book contract in the Russian publishing industry now, I would turn it down, because the Russian economy benefits from every book that is published. Publishers pay taxes, and those taxes help fund the bombs that fall on Ukrainian cities. I don’t want to be a part of that.

I find myself in this strange position where I escaped a dictatorship and came here, only to see worrisome signs.

Also, censorship there is so intense that books come out redacted. To comply with the various laws that have been passed, some publishers black out sentences, sometimes whole pages. Do I want my books to look like that? No, I do not.

SV: This is making me think of book bans in the U.S.

SS: Of course it reminds me of that. It starts small, but then the appetite usually grows and censorship grows with it. I’m not at all happy about what’s happening with book bans in the U.S. or with freedom of speech in general.

SV: So, you’re worried about what’s happening in the U.S.?

SS: Of course. Some of the things the current administration is doing are completely terrifying to me, especially as someone coming from Putin’s Russia. So I find myself in this strange position where I escaped a dictatorship and came here, only to see worrisome signs. I can’t help wondering what might happen if I say the wrong thing. Which is ironic!

SV: Did you mean for your novel to also serve as a warning to American readers?

SS: I didn’t mean the book as a warning, simply because I don’t think fiction writers should issue warnings or try to teach their readers something. I guess I’m with Chekhov on this rather than Tolstoy. Tolstoy always had an agenda, but he wrote brilliant novels that were brilliant despite that agenda. When you’re a less great writer than Tolstoy and your novel turns into a pamphlet of any sort, it’s going to be worse for it. Meanwhile, Chekhov thought that a writer’s job is simply to tell a story and show life and humanity truthfully. If you read him closely, you’ll never find what the author thinks about his characters or their situations. I just wanted to tell my story truthfully, as I saw it. I thought it was important. Readers are welcome to interpret it however they wish.

You might think this contradicts what I said earlier—that art should be political—but it doesn’t, actually. I think that, as a writer, you should engage with political topics, or any topics that interest you, but you shouldn’t try to impose your own opinion on the reader.