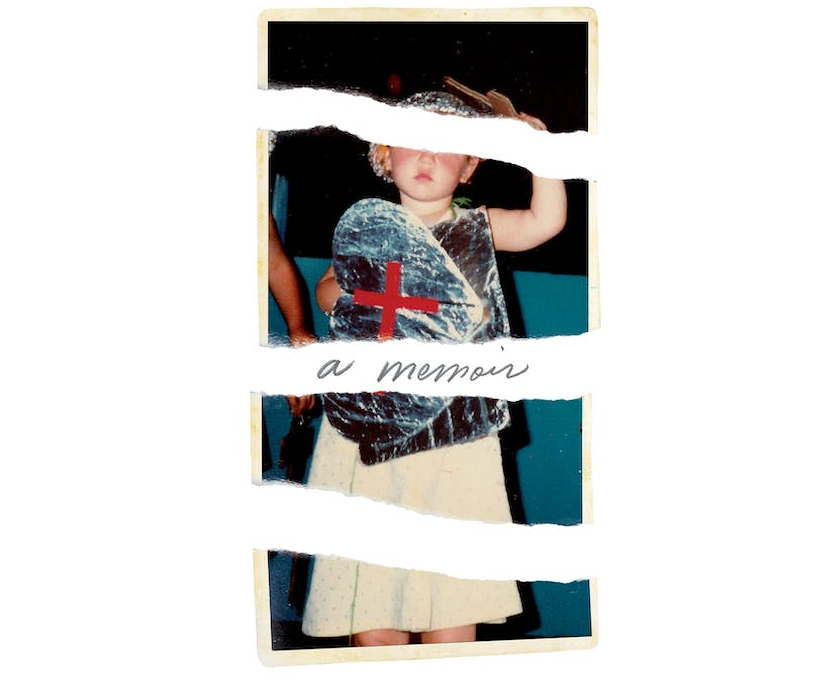

Books & Culture

As a Cult Survivor, I Found Prince Harry’s “Spare” Surprisingly Relatable

I didn’t even refer to our way of life as religion, because religion could be false

I woke up earlier than usual on the Sunday morning Princess Diana’s death was splashed across the news. I knew my mom would want me to wake her up for this. When I told her what happened overnight in Paris, she leapt out of bed and hurried to the television, where she sat in silent attention, still in her nightgown. At the time I knew it would be deeply uncool to betray an interest in European nobility, but I couldn’t look away either.

While my mom’s affection for the princess was hardly unique among midwestern mothers of the 1990’s, I suspect her fascination ran deeper. Like Diana, my mother had married at 19, and she gave birth to her first and only child the same year Diana emerged from the Lindo Wing with a young William cradled in her arms. For any stay-at-home mom, it must have been ennobling to see traditional womanhood celebrated at Diana’s level of fame while working moms in powersuits simultaneously dominated American pop culture. But my mom knew better than others what it was like to live within a rigid system like the royal family—except there were no adoring crowds cheering her on as she struggled.

Both my parents had been raised as Jehovah’s Witnesses. They accepted that their most important duty as parents was to raise their child in the faith—to teach them about the Bible, yes, but even more importantly, to teach them to live their lives as Jehovah’s Witnesses, which had less to do with the Bible than they wanted to believe. No birthdays, no Halloween, no Christmas of course, but that’s just the beginning. This way of life was all my parents had ever known, so they didn’t think to question it.

This way of life was all my parents had ever known, so they didn’t think to question it.

My mom, who sewed her own modest clothes in the 60’s when only miniskirts were available in stores, thought I was lucky that maxi skirts were in style when we went shopping for meeting clothes. My dad would tell me stories about congregation elders spying on him and his friends through binoculars when they were teens, as if to say I should just be happy I wasn’t being actively surveilled by middle-aged men.

As head of the family, my father tried to drum up enthusiasm for the monotonous routine of Witness life, which included three meetings a week—Tuesday night, Thursday night, Sunday morning—and Saturday mornings spent preaching door to door while other kids watched cartoons in their pajamas. I would sit at the end of my parents bed while my dad tied his tie for meetings and he’d lead me in a duet of an old Marty Robbins song.

“A white-”

“Sportcoat!”

“And a pink-”

“Carnation!”

“I’m all dressed up for the dance,” we sang together.

The song was from the ’50s, when my dad was just a kid himself. I imagined his father singing it with him and his brothers before meetings to get them excited—or at least willing—to sit quietly in uncomfortable formalwear on a weeknight.

The dictionary definition of a cult is so broad that almost any group of people aligned around a belief system or leader could qualify.

My mom, on the other hand, hated getting up early for Sunday Meetings, and preaching to disinterested strangers added to her sometimes crippling anxiety, yet staying at home was out of the question. Elders paid close attention to meeting attendance and hours spent preaching, and if we were absent too often we would be labeled “spiritually weak.”

There were large assemblies and summer conventions, too, where we would pack our lunches and roast in an un-airconditioned stadium alongside 40,000 other Witnesses for three straight days. On the hottest days, my mom would take an ice pack from the cooler and tuck it under her skirt while no one was looking to stay cool. We dreaded the summer convention every year, but they were nothing, my parents would say, compared to the eight-day outdoor conventions they attended as children, and it was unthinkable not to go. When it was over we would agree with the rest of the congregation that we had found it so encouraging, that we couldn’t do without this wonderful “spiritual food.”

Watching television coverage of the Windsors alongside my mom, the tiresome schedule and strict rules of royal life started to resemble life under our religion: modest dress was required, personalities were stifled to uphold an organizational image, and service to the institution was to be top priority at all times. We even had the same bizarre aversion to facial hair, and we were never to complain publicly. The Princess seemed to be chafing against the same kind of strictures with which my mother and I were painfully familiar.

Decades later, I would watch coverage of Prince Harry and Meghan’s separation from the royal family while I navigated my escape from the religion I was raised in and really begin to understand my mother’s royal fascination.

In his memoir Spare, Harry says of his family “outsiders called us a cult,” seemingly unable to leverage the claim directly. It took me a while to use the word, too. The dictionary definition of a cult is so broad that almost any group of people aligned around a belief system or leader could qualify, but the dangerous kinds of cults share common traits: They’re governed by authoritarian control, believing the leadership is always right and the only source of truth. Followers are taught that they’re never good enough. Criticism or questions are forbidden. And, most importantly, cults believe there is no legitimate reason to leave the group, that former followers are always wrong to go.

Like life in the royal family, Witness life was full of ever-shifting rules that often made little sense, but obedience to the men God had chosen to lead his organization was mandatory. In Spare, Harry is often as mystified by the arbitrary rules that dictated his life as I had been. Obedience, it seemed, was the only point for both of us.

Harry opens his memoir with a frustrating scene between himself and his brother, who can’t seem to understand why he’s left royal life behind.

“I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” he writes. “It was one thing to disagree about who was at fault or how things might have been different,” he concedes, but he cannot understand how his brother pleads ignorance of how he’s suffered. They’re having the conversation I avoided for as long as I could.

When I told my parents in an email that I was leaving the faith behind, my dad admitted that he understood why I was unhappy.

“Things haven’t always been done the best way,” he said vaguely. “But in order to accomplish Jehovah’s will there simply has to be an organization.”

Not unlike a royal justifying the existence of the monarchy, I thought. Both systems of rule ordained by God.

I’d been taught that what we believed was absolute fact.

If there’s one thing the royal family and a cult have in common, it’s the indoctrination. As Witnesses we simply referred to our beliefs as “the truth,” as if our interpretation of the Bible was beyond questioning. Growing up, I didn’t even refer to our way of life as religion, since religion could be false, and I’d been taught that what we believed was absolute fact, like it or not.

The worst thing you can do in a cult is admit it’s a cult, so for a long time I used the gentler term “high-control religion.” Even as an active Jehovah’s Witness, I couldn’t deny that the words fit, and I still worry that calling a group a cult will close more eyes than it opens. I want a better term for myself than “cult survivor” too. Cults can be life or death business, but compared to some, I didn’t have it so bad. Some didn’t survive at all.

Harry seems to have decided the name fits his family, too.

“Maybe we were a death cult,” Harry dares to suggest. “And wasn’t that a little bit more depraved?”

He describes his father pointing to the Duke of Edinburgh as an example of someone who was tormented by the press in his young years, but hailed as a national treasure at the end of his life.

“So that’s it then?” Harry asks. “Just wait till we’re dead and all will be sorted?”

“If you could just endure it, darling boy, for a little while, in a funny way they’d respect you for it,” Prince Charles replies.

The reward deferred is essential to keeping an otherwise independent adult in a system of control, and I knew those kinds of promises well. Witnesses are expected to sacrifice their own desires to earn passage through Armageddon and entry into a paradise earth. Better to die faithful and be resurrected in paradise than to seek happiness now and miss out on this glorious hope.

“Consider the Israelites,” my father urged me. “They complained about how things were being done, and they witnessed miracles…and some lost out.”

I no longer had to feign interest in the latest Watchtower article when my parents called, because they weren’t calling.

Leaving the royal family, it seemed, was a lot like leaving a cult, too. That is—unthinkable and punishable by social and familial exclusion. Witnesses can leave the faith three ways: against their will by being disfellowshipped and shunned, of their own volition by disassociating and being shunned, or by avoiding the decision as long as possible and “fading”—gradually doing less and less in the faith and hoping no one will notice.

For me—and for Harry, it seemed—the pandemic made a slow fade from our responsibilities impossible. When my parents invited me to watch the annual convention with them on Zoom, I could no longer pretend I had any interest left in the religion, or that I hadn’t been weathering lockdown with a boyfriend who didn’t share the faith. On some level, lockdown was the perfect time to be shunned—there were no parties to be disinvited from, no one was hanging out without me. I streamed coverage of Harry and Meghan’s move to California while I cut off contact with devout family members and watched friends unfollow me on Instagram.

At first, it was an immense relief. I no longer had to feign interest in the latest Watchtower article when my parents called, because they weren’t calling. I could post a picture of my boyfriend on Instagram for the first time. I could be myself.

It wasn’t until life began to return to normal that I felt what I had lost in a more visceral, even physical, way. One Saturday, before Witnesses had resumed door-to-door preaching, I passed a group of former friends eating brunch outside a restaurant near my apartment and we pretended not to see each other. I had understood that relationships within the religion were conditional, but I had also always been the one sheepishly turning my head when passing a former Witness on the sidewalk. I had been trained to treat defectors as if they were dead, but this was my first time as the ghost. I didn’t know how much these friends had heard about my decision to leave, or what stories they were telling themselves to make sense of it.

“I think deep down he knows it’s the truth,” we would often say of a disfellowshipped friend. “He just didn’t want to follow the rules.”

We told ourselves our missing friends would come back once the shunning process had worked its magic on them, and some did. But I wouldn’t, and they would never understand why.

Harry’s memoir may have set sales records, but both the book and the Prince’s post-royal publicity tour received its share of criticism.

“Even in the United States, which has a soft spot for royals in exile and a generally higher tolerance than Britain does for redemptive stories about overcoming trauma and family dysfunction,” Sarah Lyall wrote in the New York Times, “there is a sense that there are only so many revelations the public can stomach.”

Someone better versed in TikTok therapy-speak might accuse Harry of “trauma dumping.” But what they may not understand is the desire, after a lifetime of indoctrination into a bizarre way of life, to have strangers confirm what you always suspected—that you’re not the crazy one, they are. I wore out the patience of at least one friend seeking exactly this kind of reassurance, but the satisfaction of having your instincts confirmed at last is hard to resist. Finally, someone is telling you you’re right and it’s intoxicating.

When Harry told Anderson Cooper he and his wife would apologize if only his family would tell him what he and his wife had done wrong, an article in Newsweek was more than happy to provide an answer. But the question was rhetorical. If his family realized they had no answer, maybe it would open their eyes, bring them around to his side. That result was optimistic, and unlikely.

Leaving a cult requires you to let go of being right. The only way to garner sympathy from the people you leave behind is to shatter their faith, and for most of them, the cost is too high. They simply must believe in the fact of the institution they’ve sacrificed their freedom for. It’s easier to see the faults of a system that doesn’t benefit you, so the second-born son doomed to bad press coverage, or the single woman in a patriarchal religion, is better able to see the dark side of the institution that raised them. If you’re next in line for the throne, there’s so much more to lose by acknowledging the harm your beliefs do.

“I’m not interested in debating,” is all I would say to my father when he attempted to understand why I left or tried to convince me to change my mind. My parents have already made all their sacrifices for their faith and they’re waiting for their reward. To take that from them now would only hurt them.

The only way to garner sympathy from the people you leave behind is to shatter their faith.

One reviewer called the Prince “deaf to his privilege” in The Guardian, and I couldn’t help but think that perhaps our definition of privilege is too small. The privilege of leaving a palace for a mansion is undeniable. If I’d been able to afford my own apartment when my parents threatened to kick me out of the house if I stopped attending meetings, I could have left earlier. I wouldn’t have doubled-down on trying to convince myself I believed what I had been taught so I didn’t have to leave my entire life and all my loved ones behind to start over with nothing. But if I didn’t get to choose to be a Witness, certainly Harry didn’t get to choose to be a prince. And self-determination is more valuable than any trust fund. No palace or royal title could be more valuable than freedom. In that sense, Harry is only now enjoying the privilege of an ordinary person in an ordinary family.

In interviews Harry often says he hopes to reconcile with his family, that his issues are only with the press and the royal system, but I’ve learned it’s impossible to separate family from the institutions that rule them. My family and their religion are so intertwined they have become one and the same. Leaving one means leaving the other. I hope Harry makes peace with the fact that his family is the monarchy, and the monarchy is the press. And that in leaving any one of those things, he loses them all.

In the ex-Jehovah’s Witness community there are acronyms for people along the process of leaving: PIMI (physically in, mentally in), PIMQ (physically in, mentally questioning) PIMO (physically in, mentally out) POMO (physically out, mentally out) and perhaps the worst stage: POMI (physically out, mentally in). The POMI stage can be the most dangerous: it’s where ex-Witnesses, often disfellowshipped against their wishes, still believe, but find themselves unable to meet the demands of their faith. At best, POMIs languish, believing themselves disapproved by God and doomed to destruction. At worst, they resort to violence or commit suicide, hoping for forgiveness of their sins and a resurrection, a shortcut to a paradise they won’t get into otherwise.

For Harry, physically leaving could be as easy as making a phone call to Tyler Perry, but mentally leaving is the real work. Whether he makes amends with his family or not, I hope Harry can make peace with the fact that they may never understand why he wanted to be free. And I hope he can watch his father’s coronation and be happy for him—he’s finally getting the reward he was promised.