interviews

As a Writer, You’re Already Dead

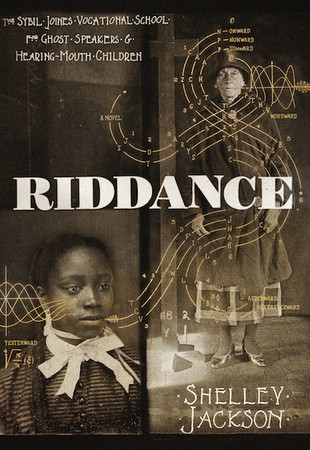

Shelley Jackson, author of “Riddance,” on the dead words that haunt her writing

I s there a difference between writing a book and making a book? I’ve worked in publishing for a bit now, and while I’ve seen how many hands go into getting one book out into the world, I’ve never fully revised my understanding that a book is written, not made. Shelley Jackson’s book Riddance has troubled this idea. Why should that matter?

Riddance follows Sybil Joines, the Headmistress and founder of the Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers and Hearing-Mouth Children. A stutterer since childhood, she founded the school as a haven for stuttering children. But she is an early explorer in the field of necrophysics. Stutterers, Sybil Joines, argues, have the capacity to communicate with the land of the dead. Their stutter is a hiccup in time that allows stutterers to straddle both worlds. These children are also a resource for her studies. Jane, a student at the school, becomes Joines’s stenographer as she travels into the land of the dead. But when a student disappears, the school starts to get the wrong kind of attention.

But story is not all this book is made up of. Riddance is a physical artifact, a material object you need to hold in your hands to fully understand. Riddance defies the existing categories we have for understanding what writing is so Jackson can make space for a new argument about what writing can do. How does she do it? In part, some of the meaning is in the making — the book is organized into chapters that break down into three repeating sections, “The Final Dispatch,” “The Stenographer’s Story,” and “Letters to Dead Authors,” and each chapter is peppered with readings from a visiting scholar’s observations on the architecture of the school or a textbook, Principles of Necrophysics. There are maps and diagrams, beautiful etches of disturbing contraptions to ease a child’s stutter.

Reading Riddance is an experience in being haunted, not by ghosts per se, but by the growing sense that writing itself is a haunted enterprise. Riddance is haunted by undead histories, undead traumas, undead authors, and undead words that were never really our own, that illuminate why a book that is not only written, but made. The parts may be undead, but Shelley Jackson has assembled them, made them through her writing, all come to life again.

Shelley Jackson and I corresponded over email about book-building, meaning-making, and the dead words that haunt our writing.

Erin Bartnett: Riddance is this great assemblage of different writing spaces: there are the “Final Dispatches” from the Headmistress, the “Stenographer’s Story,” the Readings from textbooks on necrophysics, notes from a visitor on observing the school, and then a single letter written from the Headmistress to a dead author.

What about the form — the “scholarly work with the popular appeal of a crime novel” or “the eccentric, muscled back into the white light of judgement” as the editor describes Riddance — was compelling for you while constructing this book?

Shelley Jackson: Riddance began with an essay on the relationship between language, mediumship, speech impediments, and ghosts. Though I was exploring real ideas, I did so through a fictional lens: the point of view of the headmistress of an imaginary school. More pieces followed, elaborating on the history of the school I had imagined, its customs, its philosophy, its homework assignments. When I decided these could make up a larger project, it wasn’t a novel that I imagined. I thought it might be a fake .edu web site, say, plus a scattering of supporting references around the internet, enough to create a little alternate reality, one that you might stumble upon and never quite figure out whether it was real, fiction, a lie, or sincere madness. Even once a story grew up around this material, I wanted to preserve the feeling of an archive of ephemera, related but not bound to a strict narrative throughline or single point of view.

EB: I was interested in the way you use the historical lens of the spiritualist movement. The book is in heavy conversation with the icons and landmarks of the late nineteenth/early twentieth century when the Fox Sisters, mesmerism, and hoaxes, for instance were popular. And then there are also the excerpts from textbooks and scholarly articles on necrophysics. What about that moment in time when science and spirituality were so entwined was important for you in writing Riddance?

SJ: I was struck by how these spheres that we normally think of as unrelated were for a time joined. How grief and yearning showed through the science, how fantasy and logic converged in bizarrely concrete ways — in spirit photography, in electric devices that purported to contact the dead, in detailed and pedantic descriptions of the nature of the afterlife. For a while, because of scientific advances in our understanding of reality, stranger things suddenly seemed possible. If electricity, if light, if sound — apparently immaterial things — could have measurable, material effects, then why not ghosts? Writing rests on a similar sort of faith, that feelings, dreams, ideas, memories can move the world. I’ve come to regard it as a kind of technologically-assisted mediumship. Not because I use a computer to write, but because for me language itself is a sort of machine or device, but one through which spirits blow. Maybe that’s what a human being is, as well.

Writing rests on the faith that feelings, dreams, ideas, memories can move the world.

EB: One of the most interesting pieces (and there are many!) of this book project is the way you incorporate images of men, women, and children with instruments strapped to their mouths, or scraps of attendance sheets and school records and instructions for teaching particular lessons. They create an uncanny medical history narrative of their own. I’m convinced many of them are “real” artifacts. How did you create these?

SJ: I created some of the images — the drawings of mouth objects, for instance, and the big map — and originally wanted to make all the images myself. But eventually I recognized that if they were all in my own hand (since I’m not versatile enough to convincingly imitate a bunch of different artists’ styles) it would undermine the impression of an archive of real historical ephemera. By that point, however, I had started seeing evidence of the Vocational School everywhere — at a certain stage in a big project, you’re so attuned to the themes of your book that the world outside seems to body forth your ideas completely unbidden. I started collecting found images from out-of-print books I owned or found online (19th century dentistry manuals, experimental pedagogy textbooks, books on how to “cure” stuttering, and so on). My designer did too. We manipulated some of them a little, but they were already so good, with a mysterious quality I couldn’t have created if I tried, that they didn’t need many changes to feel like part of my world.

EB: The stutter, which manifests itself physically in the mouths of the children at the Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost Speakers and Hearing Mouth Children, becomes a tool that can be used to access the stutter between “then” and “now” in which ghosts speak. The body has figured heavily in so much of your work, I was wondering if you could talk more about how your focus changes from a project like SKIN, where the literal bodies of volunteers were tattooed with words in your story, to Riddance. Can you talk about what makes the body such an important part of your work?

SJ: In SKIN I was mainly interested in the written word, in the way it bodies forth its meaning, but also competes with it. I wanted to give my words a private life of their own, setting them free to wander around the world.

In Riddance I’m more interested in the spoken word. But the body is involved in speech as well; in, specifically, the physical production of speech, this choreographed dance of tongue and jaw and vocal cords, a process which becomes all the more palpable when it’s a problem, as it is for stutterers, and how that relates to the more ethereal body that is the sound wave and its even more ethereal meaning. In a broad sense it’s the same thing I’m interested in all my writing: how meaning relates to matter. How matter means. How meaning matters. I’m interested in that first as a person, as someone who’s always been a bit bemused by being or having a body, and what the relationship is between that body and who I think I am. But I’m also interested in it as a writer and a reader, who is accustomed to handling the bodies of words, and is conscious that they are not identical with, don’t dissolve into their meaning and that for me that resistance to subsumption is exactly what makes writing writing.

EB: You’ve done a lot of work with hypertexts, and with other ephemeral or “mortal” mediums for your writing — like skin, and snow. The Headmistress, in one of her final dispatches says, “A book is a block of frozen moments — of time without time, which can nonetheless be reintroduced to time, by a reader who runs her attention over it at the speed of living.” For a book about ghosts, I wondered about these “frozen moments” in the book as a physical object. Why did you decide to make Riddance a physical, bound book?

SJ: Riddance is deeply rooted in the 19th century, and I wanted it to feel like a distant relative of the books that gave rise to it, and to take its place among them. And since I’m particularly interested in the tension between ideas and their embodiment, it felt important when writing about ghosts to make a book that took an undeniably physical form, heavy and cornered. Where ghosts are concerned (and ghosts are always concerned, in my opinion) it’s the way they rub up against more material things that interests me. That’s what a book is: a haunted object.

The Only Good Thing About Winter Is This Story Written in Snow

EB: In one of the Headmistress’s final dispatches she asks the stenographer to “turn the page” to see what happens next, but then catches herself in the error. “You cannot flip forward to a page you have not yet typed, to see what is written there. That is something time does not permit. But wait! If what I say comes true in being said, then — listen closely — if I say what she is doing there, two pages from now, as for instance ‘In two pages she will be walking up a cypress-lined drive,’ will it be true? Is it already true in being said? Can I, then, determine the future?” Many moments in Riddance felt to me, like a kind of ars poetica. Can you say more about how writing and being haunted resemble one another?

SJ: The section you’re quoting is dictated from the land of the dead, and describes the experience of traveling there, which in my very particular conception of it is very much like the experience of writing about it: In order to travel there, you have to invent at every moment both the road you’re walking down and yourself, walking. This is also, I hope, close to the experience of the reader, who if I’ve done my job should glimpse the void through the gaps between words, should feel held up only by the flimsiest of descriptions, and those subject to revision or rejection at any moment. Many of my favorite writers — Kafka, Beckett, Calvino — make a sentence feel like a tightrope whose other end isn’t fastened to anything. I suppose it is what dying must be like. Or living, come to think of it.

But writing is like being haunted in a different sense too. We’re all haunted, as users of language. Language is handed down to us from the past. The words of people long since dead are in our mouths. I think writers feel this more keenly than other people do, for the obvious reason that we are more concerned with language, and more aware of how much of what we write is borrowed (almost everything). We are spoken to and through by writers of the past, and speak back to them in our work. It is very easy to have the impression, as a writer, that you’re already dead.

Language is handed down to us from the past. The words of people long since dead are in our mouths.

EB: One of the recurring sections of Riddance is told from the perspective of the scholar studying language, who believes that language is born out of mourning. Language is fixed in some way for him. While for the headmistress, language, once freed from her “self” but “fixed on a page” brings about more interesting questions: “‘ On paper I could be anyone. There was nothing to be stuck in or to stick, only boundless elasticity, boundless subtlety, clarity, rarefaction, light and space and freedom; in a word, joy.” How did your relationship to what language can do, and the ways language makes/unmakes us change while writing this book?

SJ: Writing is more fixed than everyday speech: fixed on the page… fixed in time (while speech dies out an instant later, falls silent)…responsible to (relatively) fixed norms of grammar, usage, punctuation. But it’s also freer: not bound by the even stricter norms of everyday politesse, not bound to the first person or directed to a specific other, and above all free to invent, to fictionalize.

Of course I knew all these things already. But I would say my awareness deepened as I worked, for years, and as I tried to make my fictional philosophy as sound as nonsense could ever be. I was trying to mean what I said on some level, despite my fantastical premise, and I kind of succeeded.

EB: Jane, who is constantly being made aware of the fact that she is a black girl in a school made up of mostly white boys and girls, is haunted by the way her body has been appropriated and described by others after her mother’s death. Before coming to the school, when she arrived at her aunt’s house, I was particularly struck by the way she describes her experience being transplanted into this new language about her body she does not align with herself: “I was given a new home, new clothes, and a new body. This body had various names: stutterer, colored girl, poor relation. I did not recognize it….What I still called my self flickered around this marker, homeless and very nearly voiceless.” The children at the school are taught to listen for what is said in the silence — spoken by those who have been silenced. Does racism figure as a “silence” Riddance is trying to listen to?

SJ: Jane is an attempt to reckon with the real-world consequences of a philosophy that valorizes silence and self-erasure, like the one the headmistress promotes. Is the voluntary silence of a sovereign subject the same thing as the silence of someone denied full personhood by a racist culture? Are the consequences the same for Jane as for the headmistress, who is white? Is there actually a paradoxical power to an openness so radical that it resembles total disempowerment, or is the headmistress, blinded by her relative privilege, playing right into the hands of a not only racist but sexist and ableist culture? I may not answer those questions, but yes, I’m listening to them.

We are spoken to and through by writers of the past, and speak back to them in our work. It is very easy to have the impression, as a writer, that you’re already dead.

EB: I was hoping we could talk more widely about ghost stories. In Parul Sehgal’s recent essay on the ghost story in American Literature, she writes “Far from obsolescent, how hardy the ghost story proves as a vessel for collective terror and guilt, for the unspeakable. It alters to fit our fears. It understands us — how strenuously we run from the past, but always expect it to catch up with us. We wait for the reckoning, with dread and longing.”

Do you think the ghost story is immortal? How do you think it changes, or will continue to change?

SJ: I don’t think it’s immortal so much as undead. And as we know from the movies, the undead are really hard to kill. They just keep staggering on, losing body parts, picking up other people’s. Yes, I do think the ghost story will stagger on, in whatever form. The approaching unthinkable fact of our death is, I think, at the center of what it is to be alive, and the ghost story is a way of taking reconnaissance of that blank spot, or playing around its edges.

Stories are letters to dead authors, letters to dead readers, letters from dead authors to living readers, letters from dead authors to dead authors…

EB: I want to return to something you mentioned earlier about death and authorship. In the Headmistress’s letter to the dead author “Mr. Melville,” she writes: “Perhaps I am more comfortable with the dead than the living, though there seems to me to be scant difference between a dead and a living writer. This is not so much because dead writers seem alive in their words, as because the living ones seem already dead in theirs.” The headmistress is writing a one-way correspondence. These authors cannot write her back.

Is writing, for you, a form of corresponding with the authors that have come before you? Or perhaps even the readers who will read your work, but never “write back” in quite the same way?

SJ: Yes. Stories are letters to dead authors, letters to dead readers, letters from dead authors to living readers, letters from dead authors to dead authors… Life is a temporary condition, a sort of prep school for future dead folks. As a writer you’re always aware of the din of dead voices, and the desire to join them.