interviews

Austin Channing Brown Wants to Save Black Women Some Emotional Labor

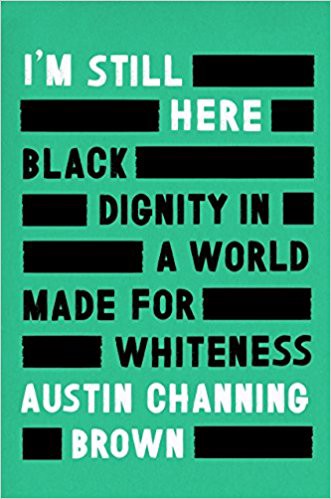

Her memoir “I’m Still Here” covers womanhood, race, religion, and white nonsense

Speaking with Austin Channing Brown about her memoir I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness was like talking to a friend who I hadn’t seen in a while. Although we have never met in person, the camaraderie was not surprising after reading I’m Still Here, which felt like snippets of someone else recanting my own experiences back to me. Brown’s debut explores growing up Black, Christian, and female in middle-class white America. She captures a collective consciousness of Black womanhood navigating white spaces that’s not only relatable but thoughtful. Her writing is accessible in ways that many of her contemporaries who write about race — Ta-Nehisi Coates and Bryan Stevenson, for example — may not be for some readers.

I’m Still Here is a truthful collection of personal stories that refuses to center white feelings, but rather focuses on white behavior patterns that affect people of color on a daily basis. Brown is a writer, speaker, and practitioner who helps schools, nonprofits, and religious organizations practice genuine inclusion. Through her personal narratives, Brown is able to discuss issues such as mass incarceration, white supremacy, and workplace discrimination, just to name a few. Her writing has appeared in Christianity Today, Relevant, Sojourners, and The Christian Century.

I spoke with Austin over the phone about who she sees as her audience, the joy of being a Black woman, parenting, white supremacy, the Black Church, and of course, Donald Trump.

TLC: When you sat down to write I’m Still Here, who were you thinking of as your audience?

ACB: Black women immediately. Black women had first priority. Every single line I wrote, I wrote thinking “how is this going to sound to the ear of a Black woman?” And then people of color. And then white folks. I remember having this “aha” moment when I first started traveling and speaking about race where everywhere I went there would be a handful of black women feeling the same way. I’d finish speaking and there would be three black women in the line saying, “Thank you for coming. I needed that.” I realized that it feels like there is only two of us but there is actually a bunch of us, we’re just spread out. I wanted to write a book that said, “I see you, and I affirm what you are going through, and your reality is true.”

At the end of the book, I start writing about [Ta-Nehisi] Coates and how he was blowing everybody away. And I said we admire Coates because he told white people the truth. I thought, “Hmm…If a Black woman reads that sentence, would that ring true?” I don’t think so. I think it is true but I don’t think that’s why we like him. We like him because he gives weight to the full history of our bodies. So, sentences like that, every sentence, I thought, “Is this true for a Black woman?” That’s why the book starts with “White people are exhausting.” I tried real hard to be clear.

Every single line I wrote, I wrote thinking ‘how is this going to sound to the ear of a Black woman?’

TLC: It’s funny that we’re talking today because I had a situation occur earlier where the first thing in my mind was “this is just white nonsense.”

ACB: That is why I tried really hard. It doesn’t mean that it worked all the time because we aren’t monolithic, but I did try to keep our thoughts, our feelings, at the center of the book, to say, “White people you need to stop doing this if you really care about us,” but to affirm who we are first.

TLC: This felt very much like a book I would give to a white coworker, someone who I feel could use a perspective outside of their own. Are you finding that reaction to your book?

ACB: I do. It’s working both ways. A couple Black women have given it to their white coworkers, which I love because it means a Black woman isn’t sitting down on her lunch break doing this work. I love that we’re saving the emotional labor of Black women. And I have a couple of stories of white women saying, “I have that one Black coworker in my life, and I am guessing she feels like this on a regular basis. I would like to give her this book.”

I love that we’re saving the emotional labor of Black women.

TLC: You talk about why you love being a Black woman. I feel you on so many things with this book and one of those is the labor involved in having to live in our bodies day to day and take on the impact of racism. How does your enjoyment of being a Black woman manifest? Is it self care? Is it a physical thing?

ACB: I’ve been trying lots of things over the course of doing this work. It varies based on the season. There was definitely a season, especially as I was writing, where I was really focused on caring for my body. I would get out every morning and workout. I was conscious of taking walks and being outside and breathing air.

After I had my son, which was during the editing process of this book, I did not pay attention to the news, especially as it relates to the killing of unarmed Black folks. I didn’t have the emotional bandwidth. I felt so tender as I look at the face of my little boy.

So, self care has changed on how I care for my body, and how I practice reminding myself that I love being a Black woman. I have found there is not just one fit. I adjust based on all the other things happening in my life, and that requires acknowledging I am more than this work. I am a mom and a wife and a human and a creative and trying to give space to all the things that I am.

TLC: I love the letter that you have for your son in your book, especially “there will be dancing” and to remember to be joyful despite the world taking those things away from us.

ACB: And we really are intentional about that. My husband plays John Coltrane at night. My son has his bedtime routine and John Coltrane. He doesn’t understand a thing that’s happening. But to create this world of Blackness and joy around him is fun.

TLC: Let’s talk about your work in the Christian community. What do you think about evangelicals and Trump?

ACB: I’ve never considered myself as evangelical. Maybe because of the Black Church. I’ve never heard that language in the Black church. So, I don’t think I ever considered myself as one. In part, that has saved me. I know a lot of Black folks who did consider themselves as evangelical and have been really hurt by what’s happened. But for me, I feel like I saw clearly when Obama took office how this was headed for a not good place. There are a lot of folks who were like, “Whoa, how did we get to Trump?” And I’m like, “Oh, I know exactly how we got to Trump.”

I remember when the country was pretty certain Obama was going to win the presidency the first time and there was a slurry of books in Christian books stores about how the world was going to end. Every new release from a pastor was about the end of the world.

TLC: I recall him being compared to the Antichrist.

ACB: So, it’s not like we had these eight years where everybody celebrated Obama, and there were no racial issues, and then all of a sudden we got Trump. Racism was growling as soon as there was a hint that Obama was going to win the White House. I think maybe the number feels high to me, that 80% of white evangelicals, but other than how high that number is, I don’t know that I can honestly say that I am super surprised because I think we could see it coming.

Racism was growling as soon as there was a hint that Obama was going to win the White House.

TLC: You worked with a lot of groups of mostly white people who would come in to Black communities and are shocked at other people’s situations. I wondered while reading your book if this was a legitimate shock or if it was a willful disregard of what they knew to be true about the world outside of their communities. Do you think these people who are pulled into the Trump machine legitimately support him or are willfully ignorant?

ACB: White supremacy contains a lot more power than America is willing to talk about. When you think about what Coates is trying to get us to think about, when you think about the full weight of slavery, when you think about the full weight of lynching, when you think about the full weight of segregation and how hard white Americans fought for segregation, when you think about genocide and the Chinese Exclusion Act, when you think about what people of color have endured for the sake of white supremacy, that is extraordinarily powerful.

And though we like to think that we have moved so far from those roots, the truth is we still are recreating the same dehumanization — separating children at the border, the way Muslims are rightfully terrified to walk around for fear of being assaulted, the killing of unarmed Black folks — the replication of dehumanization is core to what white supremacy is. Trump is shouting from the rooftops that “it’s ok, ’cause that’s how you feel, and if that is the truth about how you feel then everybody should have to accept that.” For most of America’s history that’s been true. It’s only been in recent decades that not being a white supremacist is a bad thing. There is something very appealing about Trump for those who don’t want to do the hard work of naming and dismantling white supremacy because it feels so good. Trump is giving permission to what is still alive from centuries of America’s history and uncorking a bottle that we were trying to convince folks really ought to be corked.

TLC: You also write that the Black church gave you the greatest sense of belonging. I’m curious what you meant by that and what you learned about Blackness from the Black church.

ACB: I realize that the Black church has its own problems and issues, but the sense of belonging came from the fact that [church] was a Christian face and a Black face. And for me, until I walked into that church, those things were always separate. I could go and see the Black side of my family or spend summers in a black neighborhood, but none of those things were particularly Christian. And then, on the other hand, I would be at school, and that was highly Christian, but there was nothing Black about it. But to walk into a church that contained both of those things was where I felt that sense of belonging.

I had chapel services in my school every Friday, and it was often a White guy who would get up and have a tube of toothpaste. He would squeeze out the tube of toothpaste and say, “Who thinks he can get this toothpaste back in the tube?” And, like, three kids would raise their hands and try to put the toothpaste back in and couldn’t do it. And then the preacher would say, “That is just like our words. When you say words, whether they are mean or good, you can’t put them back. So, make sure you say words that are kind.”

But then I walked into a Black church and this pastor was like, “Sister, I know you ain’t got no transportation. God has not forgotten about you.” And I was like, “Whoa, God cares about more than my toothpaste? God is interested in more than whether I am a ‘good’ person? God cares about this woman’s transportation, and He cares about this person’s family, and He cares about our neighborhood.” There were a number of things that the Black church covered and was adamant that God cared about, adamant that God loved us, adamant that god could change situations, adamant that miracles were still possible. The breadth of what the Black church was talking about was incomparable to the small simple stories about being good. It made me read my Bible completely differently.

I was like, ‘Whoa, God is interested in more than whether I am a “good” person?’

TLC: I grew up in the church. I’ve been reading a lot of posts from friends on social media who also grew up in the church and aren’t as involved as they used to be expressing dissatisfaction with the Black church, some even going as far as saying they are atheist. How do you feel about the loss of trust this generation of black people have for the Black church?

ACB: I think the capitol “C” Church, Black or otherwise, has to start think about doing church differently. The way we did church worked for a while. We have to start taking the best of what the Black church did, like justice, like music, but rethinking it. How can we do this differently? How can we embody justice more honestly, even as we seek justice in the world? How can we continue to read the Bible differently? There is a certain level of tradition that the Black church is holding on to that is not liberating. There are some things we have to risk letting go of in order to continue to be the force that ended slavery, and the force that ended segregation, and the force that has been changing the world. Until we decide that we are going to be different, I don’t know that the church is going to be able to take the lead and keep up with organizations like Black Lives Matter. I think this could be one of the first eras where the Black church is not at the forefront of finding freedom for folks.