interviews

Ayesha Harruna Attah Reimagines the Fate of Her Enslaved Ancestor in “The Hundred Wells of Salaga”

The author on using fiction to start a dialogue about slavery in Ghana

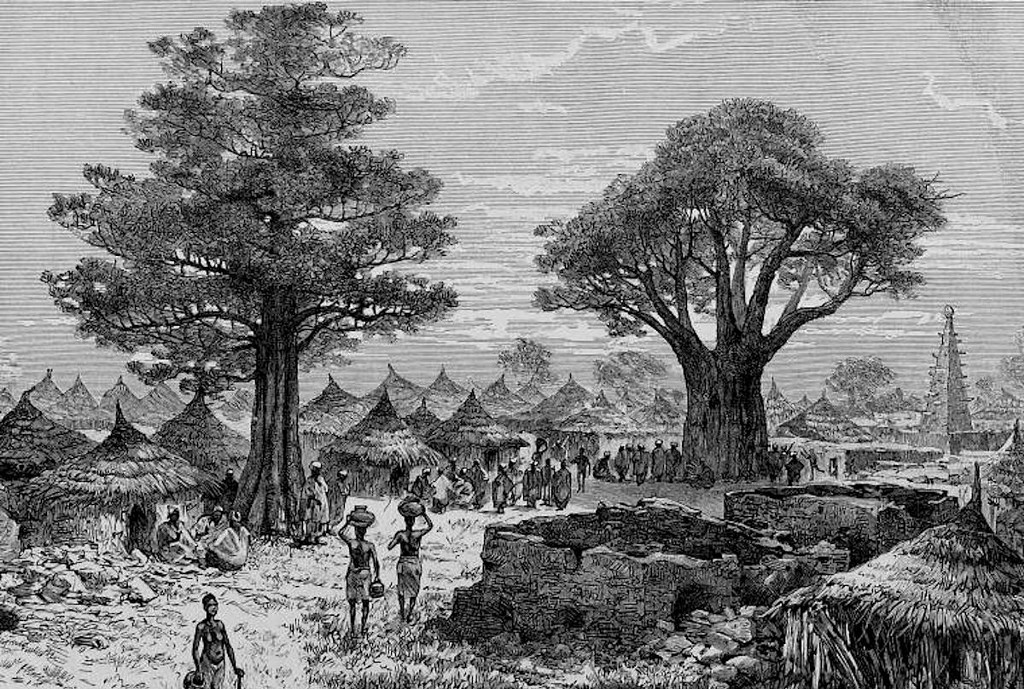

Ayesha Harruna Attah’s great-great grandmother is the force behind The Hundred Wells of Salaga, her third novel published by The Other Press. Her enslaved ancestor ended up in Salaga, a town on the southern edge of the Sahel in what is now northern Ghana. From Salaga’s market, enslaved people would be trafficked domestically or moved on to the Gold Coast and onwards across the Atlantic.

By the time of her ancestor’s enslavement and the timeframe of The Hundred Wells in the late 1900s, the slave trade had been outlawed. But in Salaga, business carried on. The Accra-born Attah reimagines the journey and fate of her grandmother in the character of Aminah, a young woman who is snatched from her village by slave raiders. On the other end of the feudal hierarchy is Wurche, a chief’s daughter, whose desire to lead is frustrated by gender expectations of her family. Through a series of tragedies, the two women are drawn together.

I spoke to Ayesha, whom I met at grad school in New York City, about retracing her ancestor’s treks, reconciling fractured histories, and living the writing life in Senegal.

J.R. Ramakrishnan: When did you first learn about your great-great grandmother’s story? How did you react when you first learnt about her?

Ayesha Harruna Attah: My father first told me about this ancestor. She was his great-grandmother. When I learned that she’d been enslaved, my initial reaction was a combination of shame and shock. It was far from the feelings of pride I’d had when I learned that we had relations to royalty. I had to unpack my emotions, why was I ashamed when this woman had done nothing wrong — if anyone had to be ashamed it was her captors (most of them royal), and people who benefited from the trade in humans. Writing this book was a look at why I felt the way I did, a chance to purge myself of the fascination with royalty, and an exploration of the texture of slavery on the African continent.

Writing this book was a look at why I felt ashamed when this woman had done nothing wrong.

JRR: Would you talk about the research that went into this novel? During this process, was there a piece of information or moment that really solidified for you that you had to write this narrative?

AHA: I wanted the family story, so I asked anyone who would indulge me for information on my ancestor. All that they knew was that she could have been Fulani, a people spread all over northern West and Central Africa; that her home could have been in Mali, Burkina Faso, or Niger; and that she was beautiful. The second part of research was going up to Salaga, to get a sense of the infamous slave market where my great-great grandmother ended up. And the third was scouring primary and secondary sources. I read through travelers’ accounts of Salaga in the 19th century, and gems such as J. A. Braimah’s Salaga: The Struggle For Power, which outlined the political activity taking shape within and outside of Salaga. There was one line in this book that cemented my resolve to write this novel. It said that princesses in Salaga could choose their lovers, even if they were already betrothed to another. It was perfect dramatic material for a novel.

JRR: The trans-Atlantic slave trade haunts the book. Aminah fears the “big water” that “had no beginning or end.” But in the novel, you focus on the complicity of Africans, royal and otherwise, in the trade via Wurche, Wofa Sarpong, and Moro. This aspect seems to have been less considered in literature than the degradations committed by white slavers. Could you speak to this perspective and how you decided to handle the writing of it?

AHA: I mentioned being shocked when my father told me about our ancestor, and I think that came from learning that her enslaver was African. I knew about indigenous slavery, but it was a fuzzy shapeless piece of information lodged somewhere in my brain. And I think that’s what indigenous slavery is to most West Africans. We know of its existence, but we push it so far back into the reaches of our minds and don’t acknowledge it. For me, realizing how close it was to home was the point I woke up. I took that amorphous piece of knowledge and took it apart and began to digest what it meant.

As I started doing my research a word kept being bandied about — “benign.” Internal slavery was supposedly not as dehumanizing as the trans-Atlantic slave trade had been, but this reasoning didn’t sit well with me. Slave raids were violent affairs where the very young and old had no chance at surviving. Enslaved people were allowed to marry into the families that had bought them, which was said to give it a different flavor from slavery across the Atlantic. To me, this still seemed like coercion and I wanted to explore what that could have looked like.

JRR: Interesting that you mention “benign.” It seems that this sentiment is often behind of some of the justification of the treatment of domestic employees, who are not enslaved but to varying degrees indentured to contracts and employers whims all over the world. What did you learn about human nature (and apparent need to organize into hierarchy) in the researching and writing this book? Anything remotely redemptive at all?

AHA: Yes, the situation of some domestic employees in parts of West Africa is no different from what Aminah would have gone through, maybe even worse. I don’t know if it’s a human need, but it has existed for thousands of years and is such a powerful system that goes hand in hand with patriarchy. What I found redemptive was the role women have always played in keeping the peace or picking up the pieces and ensuring life goes on.

JRR: Was it an early decision to have the dual POVs? Or did you come to it later on? Your grandmother inspired Aminah. How did you create Wurche?

AHA: I decided on the two points of view about three years after I started writing (it took about six years from putting down the first words till publication). At first, I focused mainly on Aminah’s story, but after I read about Gonja princesses being free to choose their lovers, I thought a woman like that would be an interesting foil to Aminah’s character who is enslaved. I did flirt with multiple viewpoints at some point, but the story needed to be told by these two women. On a craft level, Wurche was the right person to also explain the geopolitics of the region, which Aminah would have had a hard time understanding, simply because she spoke a different language, and because of her position in that very hierarchical society.

JRR: How did you personally handle the intensity of the research and its transformation to fiction? The novel doesn’t really let up with the violence. Even Wurche, who is protected by her royal class, is subject to it.

AHA: Writing Wurche’s character was one way to tone down the intensity of the violence and the feeling of suffocation I felt, even though, as you rightly point out, she is not exempt from it. I took certain liberties with her character that I couldn’t take with Aminah because I felt I had to do right by my ancestor. I was lucky to have written part of the book in beautiful places near beaches, so I would take long walks after each writing day to clear my head.

JRR: How do you expect Ghanaian readers will respond to the book? Are there people in Ghana right now who have lineages similar to Wurche’s and Aminah’s?

AHA: I have already received some reactions. I expected to hear that people weren’t ready to read a book of this sort because I sensed an unwillingness to examine our role in the slave trade. But so far, the response has been wonderful. Most people — mostly of a younger generation — have said, “I had no idea!” Others have started having conversations with their families. And one surprising detail I heard is that in almost every family, there are people who had slaves and then there were people who were enslaved.

JRR: And how do you expect the novel to be greeted in the U.S., especially by African American readers? What conversations have you had or which ones do you anticipate?

AHA: This is one African girl’s way of saying, “Sisters and brothers, I’m sorry we did this to you, I’m sorry we did this to ourselves. Can we talk? Can we build bridges?” I’m leaving myself open to discussion. I know some of it is going to be difficult, painful, even, but I hope it can be cathartic.

This novel is one African girl’s way of saying, ‘Sisters and brothers, I’m sorry we did this to you, I’m sorry we did this to ourselves.’

JRR: The other recent novel that touches upon the internal complexities of enslavement has also come from a Ghana-born writer, Yaa Gyasi, who examines the before story of slavery in Ghana in Homegoing. How is slavery taught in Ghana? How does it feature in national consciousness?

AHA: I really enjoyed reading Homegoing, which starts off in the 18th century and fans out into the diaspora, dexterously showing how the trauma of slavery is passed down from generation to generation. In my book, I stay on the home front, because that is a story that I haven’t read much of, at least in Ghana. Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Healers, also talks about the internal slave trade, in the southern part of the country. Most of the people who were enslaved were kidnapped from the north, and that’s where I set my novel.

For a long time, slavery in schools has focused on the trans-Atlantic slave trade. There are tourist sites that are directly linked to the slave trade such as the Salaga Slave Market and the Elmina Castle, where people were held in shoeboxes of spaces before being packed into boats, and the rhetoric given by the tour guides is often, “Never again.” The President of Ghana has declared 2019, the year of return for the African Diaspora, and his message has generally been the conversation at the national level, one in which Africa’s children are welcome to come home. What I’ve heard less of is: we were part of this horrible system and we are sorry, let’s get to the root of this.

JRR: What happened to the grandmother who inspired Aminah’s story?

AHA: We have no idea. Given that she was simply called the slave and no one remembers her name, I imagine she died young.

JRR: While you’ve lived and worked in New York, you chose to leave to return home and now live in Senegal. How do you feel place affects your work?

AHA: The continent of Africa is my muse so it’s important that I mostly write out of this space. From time to time, I get the chance to leave it and that remove allows me to see things clearly and not to be too precious with my stories and characters. I loved living in New York City in my 20s but it was very removed from the realities of life on the continent, so I had to get back.