Books & Culture

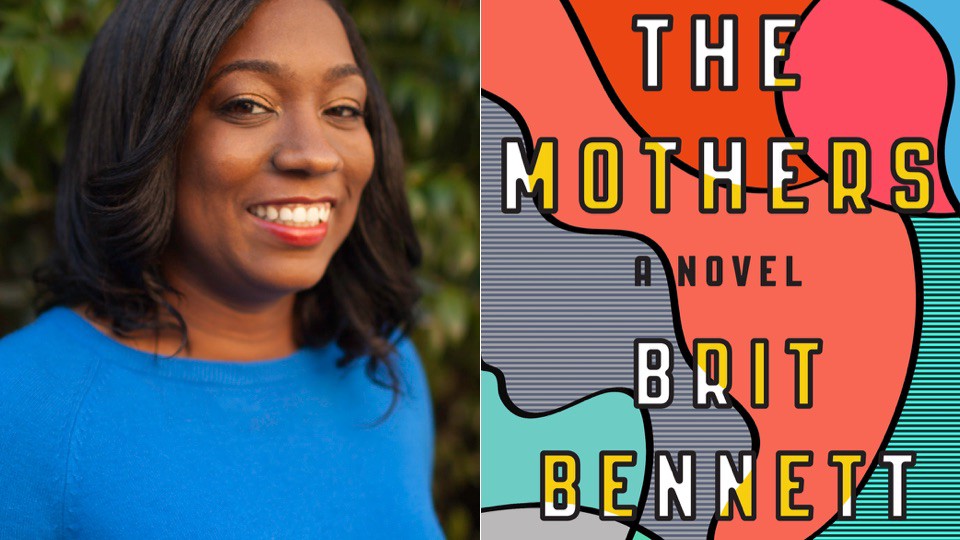

Brit Bennett on Family, Religion, and Upending Expectations of Black Narratives

“I just wanted to write a novel that would show the lives of ordinary black people and their problems.”

Brit Bennett is the author of The Mothers, a debut novel about the coming-of-age of Nadia, a young African American woman growing up in a Southern California beach town. Bennett, who until recently had gained prominence for her essays, has just been named one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35, a recognition of the best rising stars in American literature. Jacqueline Woodson, who selected Bennett for the honor, said to the LA Times: “I was truly struck by Brit’s ability to tell such a compelling and thoughtful story about community, the complexities of friendship, marriage, choices. The Mothers gives the world a glimpse into lives that are both everyday ordinary and, through Brit’s mastery, startlingly extraordinary.” Bennett lives in Los Angeles and is currently touring the US. I spoke to her on the phone on the eve of the book’s release.

Marta Bausells: How did you find out you had been selected as one of the 5 under 35? Were you surprised?

Brit Bennett: Yes, very. I was aware that the award existed, and writers I admired had been honoured, but I never expected this to happen. I have a few coffee shops I like to go to during week, and as I was working there I just saw an unknown number calling me from New York, and the first time I actually missed the call, but fortunately they called right back!

Bausells: The two main characters in The Mothers are teenagers who are growing up with absent mothers. What was the inspiration for that?

Bennett: I was drawn to the idea of this unlikely friendship between these two girls who, on the surface, you wouldn’t think would really get along, but they’re bonded by this lack of their mothers. I’m fortunate that both my parents are still alive, but losing my parents has always been a fear and it’s still something that stresses me out, particularly the idea of losing my mother and the idea of trying to grow up as a young girl without your mother there to help you. So I think those characters and their relationship originated from some of the anxiety I felt as a young girl.

Bausells: The novel starts with an abortion, which is present throughout the narrative. This experience is missing in many stories about young women in our culture, even though it’s a daily experience for many of them. Why did you decide to put it front and centre?

Bennett: Originally, Nadia and her abortion were a secret that was hovering in the background of the story. She was a minor character and, over time, as I worked on the book, I realised she was actually the engine that was driving the story forward; everything was hinging on this decision that she had made. So I decided to move her to the forefront. It’s not any type of a spoiler, it’s a plot point that is stated in the first couple of pages. Ultimately, I decided that if I was going to write about this, I didn’t want to hedge or make it this thing that was going to be swept under the rug.

Bausells: Have you been surprised by all the attention the abortion has received?

Bennett: Yes, I’ve been surprised that people are reacting so strongly to it and interested by that aspect of the book. It wasn’t an emotional decision for me to include it. I knew from the beginning that she wasn’t going to keep this baby, so it wasn’t something I really debated. But most people have responded with a degree of complexity and nuance that’s often missing from our political debates about abortion. They’re responding to the fact that these characters — who are human, and who are reacting in complicated, emotional ways — did it, and people have been very empathetic towards that, however they feel politically about abortion.

Bausells: The novel starts with Nadia coming to grips with her mother’s suicide, and she later decides to have the abortion. Her friend, Aubrey, also has an absent mother and will make a decision regarding a pregnancy. How did you conceive of a parallel between these two generations of women, between the girls’ motherlessness and their decisions over their bodies and potential children?

Bennett: For Nadia, I always knew that she wouldn’t have a mother. Originally her mother died when she was a lot younger, but as I worked on the book I realised that those decisions needed to be pushed closer together in time, her losing her mother and her getting pregnant, deciding not to be a mother. Because I thought the way that that reverberates off each other was interesting, the idea that you’ve just lost your mother in this very sad, confusing and tragic way, and you’re thinking “I’m not ready to be somebody’s mother.” I think at that point she really is looking for someone to take care of her, she’s not in any position to take care of somebody else.

Similarly, with Aubrey, having this really rough childhood and this very complicated relationship with her mother, and her mother not protecting her in a way that she should have, definitely affects the way that she thinks about the possibility of having a child and what her relationship to that child could be. This was something that came about a little later, but I realised that, generationally, we inherit these things from our parents, whether we realise it or not.

Bausells: The Mothers centers on these two girls’ relationship, and it’s a beautiful and precise portrayal of female friendship — with all its glory and drama, love and treason. Where did you draw that from?

Bennett: A lot of it is drawing from idea of being a young woman and thinking how important my friendships with my female friends are at this point in my life, and particularly when I was younger and in high school. Friendships, particularly friendships among women, are often trivialised and considered less important than the romantic relationship, which is supposed to be the real center of your life. But that’s never been true in my life. And it was something that I wanted to explore: the intimacy of friendship, and the way it can be source of love but also source of betrayal. The idea of having a falling out with my best friend is, in a lot of ways, more devastating than the idea of going through some type of romantic breakup.

Bausells: The story is narrated by this gossipy voice of wisdom, one of “the mothers” of the church who watch the story unfold. How did that come about?

Bennett: It happened by accident and pretty organically. I had written the whole book in the third person, with a gossipy tone — actually, the first sentence of the novel has been the same for years: “We didn’t believe when we first heard because you know how church folk can gossip.” Towards the end of writing it, I decided to play around with it and see what would happen if I actually located that voice, the Greek chorus of church mothers, as the ones who are observing what’s going on in the community, and narrating and commenting. I had a lot of fun writing that, and channeling the voice of these older women whose comments, judgements and indictments of younger people I’m used to receiving.

I’m the youngest person in my family, so I’m used to being the eavesdropper when older people are talking around me. I realize I have a lot closer connections to older people than I do to younger people. I don’t have children in my life, but I feel very comfortable sitting with a group of 60- or 70-year old women talking. Those voices came from thinking about these things I’ve grown up hearing, about life, and about men, religion, and what type of woman I should be.

Bausells: Where would you like to see the book placed in the culture? There seems to be a lot of attention to the fact that it’s about black characters, even though that’s not the focus of the story.

Bennett: Ultimately, my biggest dream for the book was for people to read it and connect with it. I love being able to go and talk to people, and to have people telling me they were moved by the book, particularly a lot of young women who have been reaching out to me about it. Young women who’ve had abortions who are just glad to see that experience represented in a non-judgemental way. So I’m grateful for that.

The two questions I get asked the most about the book are about abortion and about race, which is interesting. I don’t mind having those conversations, because I wrote about black characters who are engaging with ideas of race. It’s on the page, so it doesn’t bother me that people are reading that. But it’s a little surprising to me. I’m reading The Wangs vs. the World right now, about an Asian American family — and this is just the background of these characters, these are the terms of the work, in the same way that The Mothers is a book about family, and religion. It’s a book about black characters, but I think there’s a way in which people are reacting to the characters — and their not conforming to what is expected — which has been very telling of what people think or expect about black narratives.

I’ve lived my life in a lot of very white spaces. I know black lawyers; black doctors, black people who live in inner cities; who live in rural areas; but also black people who live in suburbs…and I went to Stanford, I remember meeting black kids who were friends with the Obamas! The gamut of all types of people from different classes and backgrounds, all types of people — black people are as diverse as any group of people, which should go without saying! But it’s becoming increasingly clear to me that that’s shocking or surprising to people in a way that I just didn’t think it was.

Black people are as diverse as any group of people, which should go without saying!

Bausells: I guess it’s the classic thing of taking whiteness as universal, and whenever a story features non-white characters, assuming it is about race, when no one would ever talk about The Mothers being about race if your characters were white.

Bennett: Exactly. It’s a book whose characters have racialized experiences and perceptions, but their major conflicts are not racism. There could have been any race of girl who finds herself in that situation, but I think it matters that Nadia’s black because she’s aware of stereotypes, she’s aware of expectation, so that affects her thought process and affects her emotions, but it doesn’t affect the plot in and of itself. Which I think is often how life is. I just wanted to write a novel that would show the lives of ordinary black people and their problems, and show these characters and these communities in ways that would be complicated and interesting.

Bausells: In your nonfiction, you have written essays on police violence and systemic injustice (like that Jezebel piece that led you to your agent). You’ve talked about feeling ambivalent about your professional success happening among profound suffering.

Bennett: After I wrote that piece, I just felt like I didn’t know what else I had to really say about this. I respect the people who are out there exerting the emotional energy and the creative energy to write in this moment, and I don’t want to feel like I’m sort throwing in the towel, but I also reached a point where I was like: I don’t know what else I have to say besides saying that black lives matter and that this is wrong and there should be accountability. Who am I writing for, who am I trying to convince of this? If you’re someone who’s not convinced by watching a video of someone being shot, why would my essay convince you?

If you’re someone who’s not convinced by watching a video of someone being shot, why would my essay convince you?

I don’t know, it could just be where I am right now. It’s something that I’ve been really thinking about, wanting to spend my emotional energy and my creative energy towards something that feels fruitful … And not screaming until I’m blue in the face that black lives matter to people who are unwilling to accept that black people should deserve full humanity and full freedom.

My ambivalence came from the fact that this Jezebel piece that was this great professional moment for me happened among this deep personal sadness about what was going on in the news. Also, there’s a way in which I think we feel like we have to constantly make black pain visible so that it’s real. It’s like no one will believe that police violence is a problem unless they see a video. And we’re going watch this video of a black person being gunned down over and over and over again, and that’s the only way, maybe, you might believe that this is a systemic issue. I just realised I didn’t want to necessarily participate in that, in this idea that I have to make black pain visible so that white people feel it or they realise that it’s real. I don’t know, I’m not saying never. I only want to write things that I feel are important or necessary, if I feel like I have something new and interesting to say, so that moment might pop up, but I sure hope it’s not because another black person is killed.

Bausells: What moves you, besides writing?

Bennett: My life is very boring! This is as exciting as it gets. I try to find things that are not word-related to do, because I spend so much time with words. I’m not writing or reading, I do really like TV — I’m almost overwhelmed by how much good TV is on right now and I’m really excited about a lot of fall TV — and I’ve been thinking about this idea of black narratives again. I recently watched Atlanta and then I followed it with Insecure — and again, they’re just contemporary stories, regular black people, regular problems, different parts of the country, different communities, different stuff happening with class — and it was just such a cool thing to watch shows with black-to-black conversations and all of these just characters who are complicated and flawed. But the fact that that was a moment I noticed is sad! It’s a sad state of media, because I’d never think that if I was watching a show with white characters. There’s something very exciting about what a lot of black artists are doing right now.

Bausells: What’s next?

Bennett: I’m currently halfway through the first draft of my next novel. It’s about a pair of sisters who get separated and one is trying to find the other. It begins in Louisiana. I still have to figure out what it is … I have no idea where it’s going to go.