Books & Culture

‘Call Me By Your Name’ Made Me Realize What the Closet Stole From Me

Both novel and movie are perfect expressions of unabashed gay teenage love

I t’s not like I didn’t know what I was getting into. After all, I’d picked up André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name mostly out of a desire to read for myself a certain juicy scene involving a peach and a much too-horny teenager that friends kept whispering and snickering about. But as I made my way through the story of the precocious Elio and his obsession with Oliver, the dashing graduate student saying at his family’s Italian villa for the summer, I found myself blushing — not (just) at the sumptuous sex scenes between them, but at the musings on yearning and desire that make up the bulk of the text. Reading Aciman’s novel took me back to those cheek-flushed days when I’d pine away for boys I both hoped would fancy me and worried would never notice me at all. Feelings I’d long forgotten and thought I’d finally outgrown kept flooding back in ways that embarrassed and, I have to admit, titillated me to no end.

Told in the first person, Call Me By Your Name is a novel about longing. At seventeen, Elio is that shy if outgoing kid who hides behind his know-it-all attitude. “Is there anything you don’t know?” Oliver asks him at one point, in response to yet another mini-lecture on music, history, or the classics that Elio has thrust upon him. With a doting academic father and a loving liberal mother, whose laissez-faire parenting encourage his own independence, Elio is used to being in control of the perfectly constructed world around him. The feelings that erudite and attractive Oliver inspire in him vex Elio in ways he cannot begin to comprehend until he attempts to reconstruct them years later. In the novel, an adult Elio sets out to tell us about that fateful summer in the 1980s when he realized “that wanting to test desire is nothing more than a ruse to get what we want without admitting that we want it.” And hoo boy, is there a lot of testing and edging into uncharted territory throughout the book.

I may be close to twice Elio’s age, but reading the musings of a lustful and hungry 17-year-old felt all too familiar. This is, perhaps, because much of our vocabulary for desire is couched in youth. The feelings of sheer abandon, of an attraction that you can’t control, have been construed as signs of immaturity. Puppy-love, crushes, infatuations — these are things you’re supposed to outgrow. There’s nothing more ridiculous-sounding than a 33-year-old pining away, wondering whether that cute boy who just inched closer was giving him a sign.

But this is the reality, and one that Aciman nails: love (and it is a kind of love) makes words fail. His novel may make no room for the closet or the shame many of us grew up with, but it still pushed me to remember how desire, especially the kind that looks to be unrequited, can be paralyzing. When he is around, there is nothing you do that is not done for him, for his attention. But it also forces you to evaluate everything they do with the same attention; just as you are constantly crippled by the hope that they’re watching you intently and reading into everything you’re doing (say, noticing your guitar playing skills or any slight change in appearance), you’re driven by the conviction that they must be equally fixated on their own demeanor, eager to have you read into their behavior the very attraction you’re projecting and internalizing in equal measure.

Aciman’s novel pushed me to remember how desire, especially the kind that looks to be unrequited, can be paralyzing.

It’s no surprise than Elio succumbs to that most dreaded of pitfalls: imitation. “I tried imitating him a few times,” he admits. “But I was too self-conscious, like someone trying to feel natural while walking about naked in a locker room only to end up aroused by his own nakedness.” The novel plunges you deep into this mirrored sensibility where desire and identification are intertwined. As is obvious from its title, Elio’s plight is sutured to the near-narcissistic idea of same-sex desire. “Call me me by your name and I’ll call you by mine,” Oliver tells him as they lay in bed in post-coital bliss once they finally give in to their lust for one another.

That’s when it struck me that my blushing wasn’t just about remembering first crushes and feeling that sense of possibility anew. Entangled in my own all-too physical reaction to the book was the reminder that, unlike Elio, I’d never quite been able to indulge in such knee-buckling attractions. Definitely not in my teenage years. To read about Elio’s summer affair with Oliver was to be reminded of the way I’d forced myself to closet such desires. Where friends and schoolmates got to live out teenage flings with abandon, accruing the kind of anecdotes that would later inform the relationships in their 20s, 30s, and presumably beyond, I’d spent too many years denying my own attraction to other men. Part of why reading such nakedly sexual and unabashedly erotic longing in the voice of a 17-year-old embarrassed me was because I could only belatedly identify with it. I’d never been able to be Elio in my youth but could all too easily be him in my 30s.

Part of why reading such nakedly sexual and unabashedly erotic longing in the voice of a 17-year-old embarrassed me was because I could only belatedly identify with it.

It’s why I worried about encountering him on the big screen. So much of the novel takes place in Elio’s head, with his near-insufferable soliloquies on desire, that I worried director Luca Guadagnino and screenwriter James Ivory wouldn’t be able to capture the very thing that had stirred such youthful (and shameful) feelings in me. I shouldn’t have worried. In the hands of Timothée Chalamet, Elio comes alive in ways I could never have dreamed of. Thankfully stripped of any kind of tired voiceover, Ivory and Guadagnino opt instead to let Elio and Oliver’s interactions brim with a physicality that speaks volumes. Elio’s bumbling walk whenever he’s moving in Oliver’s direction, as well as the infinitesimal changes in posture whenever he sees Oliver’s eyes alight on him, telegraph the many moments of interiority Aciman’s novel so depends on. The self-consciousness that comes across in Elio’s prose has been internalized in Chalamet’s body which, like a compass, is constantly looking for its North in Oliver.

And if words are “futile devices,” as Sufjan Stevens croons in one of the songs in the soundtrack, it’s no surprise Elio turns to actions — outlandish ones at that — to project exactly how he feels. Here’s where the film itself made me blush just as intently as the novel. Since they share adjacent rooms, Elio oftentimes sneaks into Oliver’s room to survey the realm of the man he desires. In one instance he happens upon one of Oliver’s recently-worn swimsuits. And, in what has to be one of the most sensual moments of the film (yes, even more than that peach scene) Elio splays himself out on all fours in Oliver’s bed as he wears the red shorts over his face and inhales the musky odor therein. I’m usually very composed while watching films, especially when surrounded by hundreds of other viewers as I was the night I first caught Call Me By Your Name at the New York Film Festival. But, during this scene, I quickly felt my pulse quickening and my palms getting increasingly damp. How many times had I fantasized about being so bold, so shameless? I thought back to instances where I’d been left alone in another man’s bedroom (while I took a phone call, or while they took a shower) and I’d kept myself from plundering their dirty laundry to get a whiff of the intoxicating smell that so drew me to them. Gladly, just as when I’d read (and later re-read) Aciman’s novel, there was no way others could see how flushed I got when I saw Chalamet all but convulse at the joy he felt upon inhaling Oliver’s smell.

The Queer Erotics of Handholding in Literature

But I blushed furiously in the dark, and also, I cried. Not only had Elio and Oliver survived their translation to the big screen, but in the process, they’d managed to further burrow themselves into my heart, making me both giddy and melancholy about having them in my life, if only for a short while. Seeing them biking along dirt roads, swimming in pools, groping one another inappropriately, and later embracing the electric connection they’ve inadvertently stumbled upon, they reduced me to a smitten schoolboy. And, like Elio in the final moving frame of the film, when the prospect of it all being over leaves him in a pool of tears, mourning something which had yet to be, I was a sobbing mess.

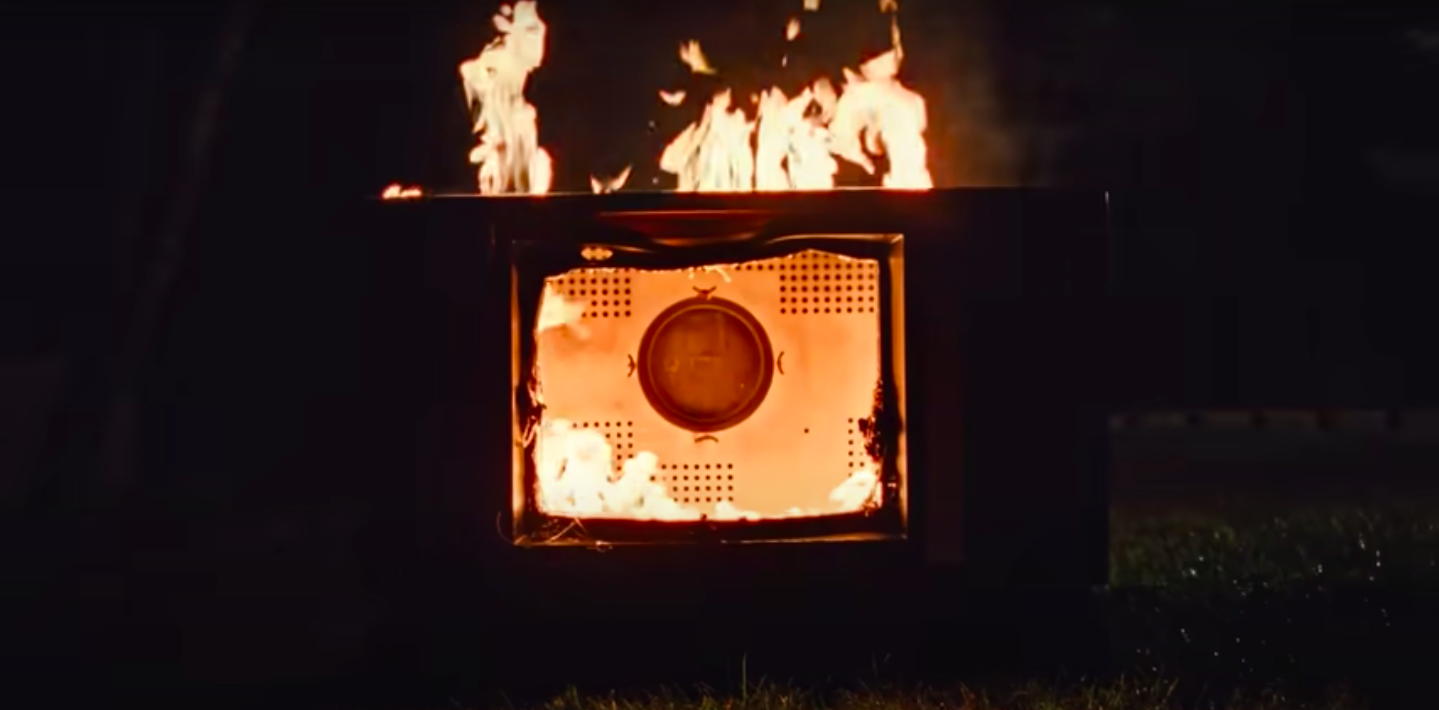

Part of wanting is understanding that those feelings have a depressingly short shelf life. Nothing quite like what Elio felt for Oliver could last long even (especially) after it was consummated. The emotions endure only as prized memories, mere flashes of lightning in darkness; or, as Guadagnino presents them at one point when we see Elio reminiscing, as overexposed and highly saturated images that brim with brightness, make everything else seem dull, but also singe your sight if you watch them for too long. And that’s where the ultimate if predictable tragedy of Call Me By Your Name lies: in its portrayal of the blistering ephemerality of longing. The way its flame engulfs you, making you unable to know whether you’re being warmed or burned. It’s no surprise Elio’s father, speaking to his devastated son after Oliver departs, instructs him to nurse his pain. “And if there is a flame,” he adds, “don’t snuff it out, don’t be brutal with it.” They’re words I could’ve used at 17, for sure. But they rang, in between blushes and tears, all the more poignant at 33.