Books & Culture

Calvin and Hobbes Gets Christmas Right

Looking for moral complexity in holiday literature

In Santa’s shop, just as he’s arranging his sack of presents into his sleigh, an elf reminds Santa about a problematic six-year-old boy. “There’s still the matter of this Calvin, sir,” the bespectacled elf says. “His list is 30 pages long, not including the supplement about incendiary weapons. The research dept. thought you should handle this one personally.” The elf hands Santa a thick dossier on the notorious child. Although the elf reveals that “surveillance documents some 400 incidents” that might put Calvin on the naughty list — which Calvin tries to explain away in his file through “extenuating circumstances” — the elf notes that “a tiger vouches for the kid’s character…says the kid tries to be sort of good if he’s not tempted otherwise.”

Santa makes up his mind and puts on his coat with a smile; meanwhile, Calvin can’t sleep due to the “suspense” of not knowing if he will get gifts from Father Christmas. This absurd yet meaningful episode sums up much of Bill Watterson’s Christmas-themed Calvin and Hobbes strips, which are not only valuable additions to the canon of Christmas literature, but which may also be some of the most representative of the holiday’s complexities — even more than an iconic text like Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

It can be difficult not to make a Christmas narrative feel on-the-nose about ethics on the one hand, and a celebration of commercialism on the other.

What is the literature of Christmas? Defining it, like defining many literatures, is more complex than it may appear on the surface. Literature that uses Christmas as a focal point is perhaps the easiest definition, with many such texts aimed primarily at younger audiences, like Dr. Seuss’ iconic tale of the green Grinch and Chris van Allsburg’s The Polar Express. Christmas texts for adults are a little rarer, but they include memorable texts like Dickens’ novella A Christmas Carol and Truman Capote’s lovely 1956 short story, “A Christmas Memory.” In the early nineteenth century, Washington Irving wrote a number of pieces centered around Christmas; one of his most influential was his 1809 Knickerbocker’s History of New York, which, in its satirical recording of Dutch colonial traditions, may have helped to cement some of the Christmas iconography so popular today. Notably, Irving described how “the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children” — and this was fourteen years before the New York Sentinel published perhaps the season’s most iconic text, “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” the poem often credited with originating many of the features still associated with popular depictions of Santa Claus today.

At the time Irving published Knickerbocker’s, New York had no Christmas; the only winter celebration was New Year’s. Irving also described in his later 1820 Sketch-Book traditions that, at the time, were disappearing, like kissing under mistletoe; that they exist today likely owes some debt to him. It can be difficult not to make a Christmas narrative feel on-the-nose about ethics on the one hand and a celebration of commercialism on the other, though the best writers of such tales are able to subvert both, while still drawing from cultural traditions.

Of course, it is easy to romanticize the holiday if our gaze and our memories are narrow. For someone like me, who is not religious, the holiday can feel frustrating, if family members or friends subtly or overtly try to convert you to a system of belief. Those of us who cannot afford to give presents, those of us who do not even have heat in our homes when the winter comes, are largely unrepresented in endless media images of Christmas defined by glittering warm homes, tall trees that shimmer like stars, presents. Some of us have lost the families we might once have gone home to; as a queer woman who came from a Caribbean island where being queer is often met with rejection or violence, returning home is no longer as simple as it was before I came out, and a small word like “family” can suddenly seem vast, strange, unfamiliar.

Those of us who cannot afford to give presents, those of us who do not even have heat in our homes when the winter comes, are largely unrepresented in endless media images.

And many places, like where I grew up, have snowless Decembers, even as much of the American-influenced media in my island — even local news stations and ads, sometimes — used images of snowflakes and snowmen to identify Christmas. Christmas, like most things, is made up of many stories. Yet I still saw something of myself in Calvin’s perpetual struggle with whether or not to throw a snowball at his neighbor, Susie Derkins; I might have thrown an old mango instead, and my sledding might have been letting the soft current of a shallow river dotted with black stones take me for a bit. But Calvin lived in the island for me as much as he did on the page.

What makes Watterson’s Christmas comics so resonant, to me, is how human they manage to be, how much they are premised upon failure. “I often use the Christmas season for Calvin to wrestle with good and evil,” Watterson wrote about his Christmas strips in The Tenth Anniversary Book. “He wants to be good, but for the wrong reasons.” He isn’t a role model, but he is certainly an existential model, filtered through the prism of a suburban six-year-old blonde American boy, of what it all too often means to be a person. Whereas Dickens’ didactic novella, A Christmas Carol, teaches a simple but significant lesson of kindness that Scrooge appears to take to heart in the end, Watterson’s comics are not so much didactic as they are demonstrations of something that seems even more human than Scrooge’s conversion to goodness: the fact that we are fallible, and will likely fail again and again to be good, though once in a while we may get it right.

When Scrooge is shown the error of his miserly ways — most notably, the fact that not only are people not upset by his future death but are actually relieved he is gone; and the death of Tiny Tim — he seems to undergo a profound volte-face. He not only vows to help Bob’s struggling family in a myriad of tangible ways but becomes “better than his word,” doing “infinitely more” than he had promised, as well as taking on a the role of “a second father” to Tiny Tim; beyond this, the narrator reveals that Scrooge “lived upon the Total Abstinence Principle, ever afterwards; and it was always said of him that he know how to keep Christmas well, if many man alive possessed the knowledge.”

Scrooge is now something that few, if any of us, can truly be: perfectly good.

Despite having “no further intercourse with spirits,” Scrooge has transcended this earthly plane, in a way: he is now seemingly perfectly good. He has become an idol, an ideal, a phoenix of ethics. To be sure, not everyone readily believes in or accepts Scrooge’s stunning transformation; some people even “laughed to see the alteration in him,” perhaps because the contrast was so extreme. But Scrooge is now something that few, if any of us, can truly be: perfectly good. As genuinely heartwarming and, in its own way, universal, as Dickens’ tale is, there is also a kind of moral artificiality in it in the end due to how unswerving Scrooge appears to be in his newfound charity. Scrooge, like Mr. Gradgrind of Hard Times, represents a principle more than a person — and while this does not take away from my enjoyment of A Christmas Carol, it does make it seem less like an archetypal tale of the holiday than a guide to being good.

Calvin and Hobbes, by contrast, shows something more realistic. A Christmas Carol, like many fairy tales and fables, has a cautionary message for its audience; Calvin and Hobbes manages to relay a similar message, but in a much less one-dimensional way, a way that accepts failure and indecision, a way that is more human because of it. “When the strip captures real moments,” Watterson wrote in The Tenth Anniversary Book, “without making them saccharine and tidy — my work is very satisfying.” And Scrooge’s conversion, while certainly meaningful, does feel tidy; does Scrooge never feel tempted to return to his old ways? Does anyone ever change so utterly?

In a lovely, largely wordless Sunday strip, Calvin is preparing to hit Susie with a snowball, grinning devilishly as he scoops the snow. As he raises his arm to fling the projectile, Hobbes calmly interjects. “Some philosophers say that true happiness comes from a life of virtue,” he says, hands aristocratically behind his back, before walking off. Calvin pauses, looks at Susie again, then drops the snowball. In a series of panels without dialogue, Calvin, to the shock of his parents, begins doing all the good things he normally avoids: cleaning his room, taking out the trash, doing his homework, giving his mother a card with a heart on it, shoveling the snow, setting the table. He finishes in a panel surrounded by pure white, an old slate brushed clean — except that he becomes frustrated a panel later, then runs off and knocks Susie into the snow with a snowball, laughing like a supervillain. “Someday,” he tells Hobbes, “I’ll write my own philosophy book.” Hobbes responds that “virtue needs some cheaper thrills.”

While this strip doesn’t necessarily give us a moralistic lesson, it does provide one for life: it’s not easy to change who we are, and sometimes terrible things give us the most pleasure.

Calvin may not have learnt anything that makes him as good as Scrooge — but the difference is that Scrooge stops at that panel surrounded by blankness, content with his newfound charitableness. And while this strip doesn’t necessarily give us a moralistic lesson, it does provide one for life: it’s not easy to change who we are, and sometimes terrible things give us the most pleasure. Calvin and Hobbes, as this strip demonstrates, is not an ethics pamphlet, even as it suggests that being good — not throwing that snowball — is probably the better thing to do, even as it shows that many of us comically fail to do the right thing for the right reason. “Calvin usually learns the wrong lessons from his experiences, if he learns anything at all,” Watterson wrote. To see a world in a ball of snow, as Blake might have put it.

And when Calvin finally does do something genuinely kind, as by affirming his loving friendship with his tigrine companion — who is often his sarcastic, yet never sermonizing, moral superior — it means so much more because it’s such a change from his avaricious plans to get onto Santa’s good list. Greedy as the six-year-old is, Watterson’s own Christmas carol of sorts — a beautiful single-panel strip with a poem about Christmas eve, with Calvin lying against the tummy of a napping Hobbes, a fire behind them — has Calvin say that “tomorrow’s what I’m waiting for, / But I can wait a little more.” Temperance and loving friendship come together here — and it reveals what has always been the case about Calvin: that he may do many bad things, but at his core, he’s not a bad kid, something that describes many of us better than the extremities of Scrooge’s transformation.

It is possible these heartwarming little moments were homages to one of the comics that Watterson often held up as a primary influence, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, which occasionally showed protagonist Krazy doing charitable deeds on the holiday for no reason other than their kindness, like giving coal briquettes to a poor family so that they might have warmth in the winter. And although Dickens was not a fan of evangelizing his beliefs, there is still an element of this in the end of A Christmas Carol; I prefer the more open, secular approach of Watterson’s strips, which neither endorse nor attack any particular set of beliefs.

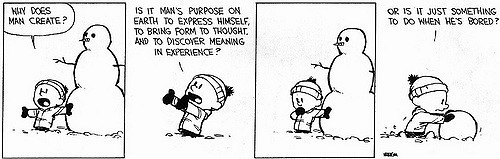

The strip’s winter landscapes, too, are suggestive. Often wide open with white space, Watterson wanted to present the spare, austere atmosphere of a Japanese woodblock print. This openness is also an emptiness, a presence in absence, and it perhaps subtly reflects the comic’s continuity when it comes to ethical struggles: each new winter (or are they all, somehow, the same December?) is a kind of blank slate for Calvin, a fresh chance to try to get onto the good list. And Watterson often uses the landscape to explore ethical questions, with Calvin asking Hobbes about anything from the value of being good to the meaning of life while zooming down a snowy slope on a sled — usually ending with a crash.

Watterson uses the landscape to explore ethical questions, with Calvin asking Hobbes about anything from the value of being good to the meaning of life while zooming down a snowy slope on a sled.

Perhaps the most memorable inhabitants of his winter landscapes are the strip’s iconic, extraordinary snowmen, which also show something of the season. As Watterson said himself in the Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book, he often used the strip to “make fun of the art world” — and, more specifically, to satirize what he saw as the ever-widening gulfs between art, largely inaccessible academic interpretations thereof, and audiences who had little to no formal study in art history and who thus were in a sense barred from the works on display.

Watterson perhaps aims a bit too broadly here, in that sometimes art truly is meant to be difficult or even, on its surface, absurd; art, after all, may be one of the most difficult words to define, even as many people think they know it when they see it, as Justice Potter Stewart famously said of pornography. But there certainly is merit in many of Watterson’s critiques, particularly when he draws ironic connections between artists who at once spurn the public and yet wish to profit off of this same public. And in a bigger sense, the snowmen also reflect both the artificiality and evanescence of Christmas. They are caricatures of a superficial kind of art; all the same, they are often glorious. And the fact the snowmen will inevitably melt is a testament, both sarcastic and serious, to the impermanence of art and its creators alike.

They are both satires and affirmations of art; after all, in one narrative that gave its name to a collection, Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons, Calvin’s grotesque creations come to life, much to his horror. The decorations we may put up during the holiday will come down, just as the snowmen will melt, but there can be joy in doing something so short-lived.

Failing is not uniquely human, of course; but failing to do good, then trying again even when one feels conflicted, certainly is, and this is the virtue of Watterson’s wonderful strip. “The best presents don’t come in boxes,” Hobbes tells Calvin one Christmas morning as Calvin gives his friend a hug — despite having forgotten to give his tiger any other presents — and these lovely moments, set against hitting people with snowballs, crashing into frozen ravines on sleds, and asking Santa — in an alphabetized list — for rocket launchers, make the strip a powerful statement for the season. It may not be universal in every respect. And it’s more and more difficult for me to let go and laugh as I remember, each day, the darkening political climate that is approaching. But art can help us through. And Watterson’s Christmas comics, as meaningful in the 1980s and ’90s as they are in 2016, transform the season into art like the best such stories.