interviews

Caoilinn Hughes on Writing About Climate Change and Women Who Center Work in Their Lives

In her new novel "The Alternatives," three Irish sisters reunite in search of their missing sibling

There’s a video that made the rounds online a few years ago: in Chechnya, a mother films her son pulling a sheep free from the drainage ditch it wedged itself into. Three glorious seconds of freedom follow for the liberated sheep, at which point it leaps majestically and comically back into the drainage ditch, stuck once more.

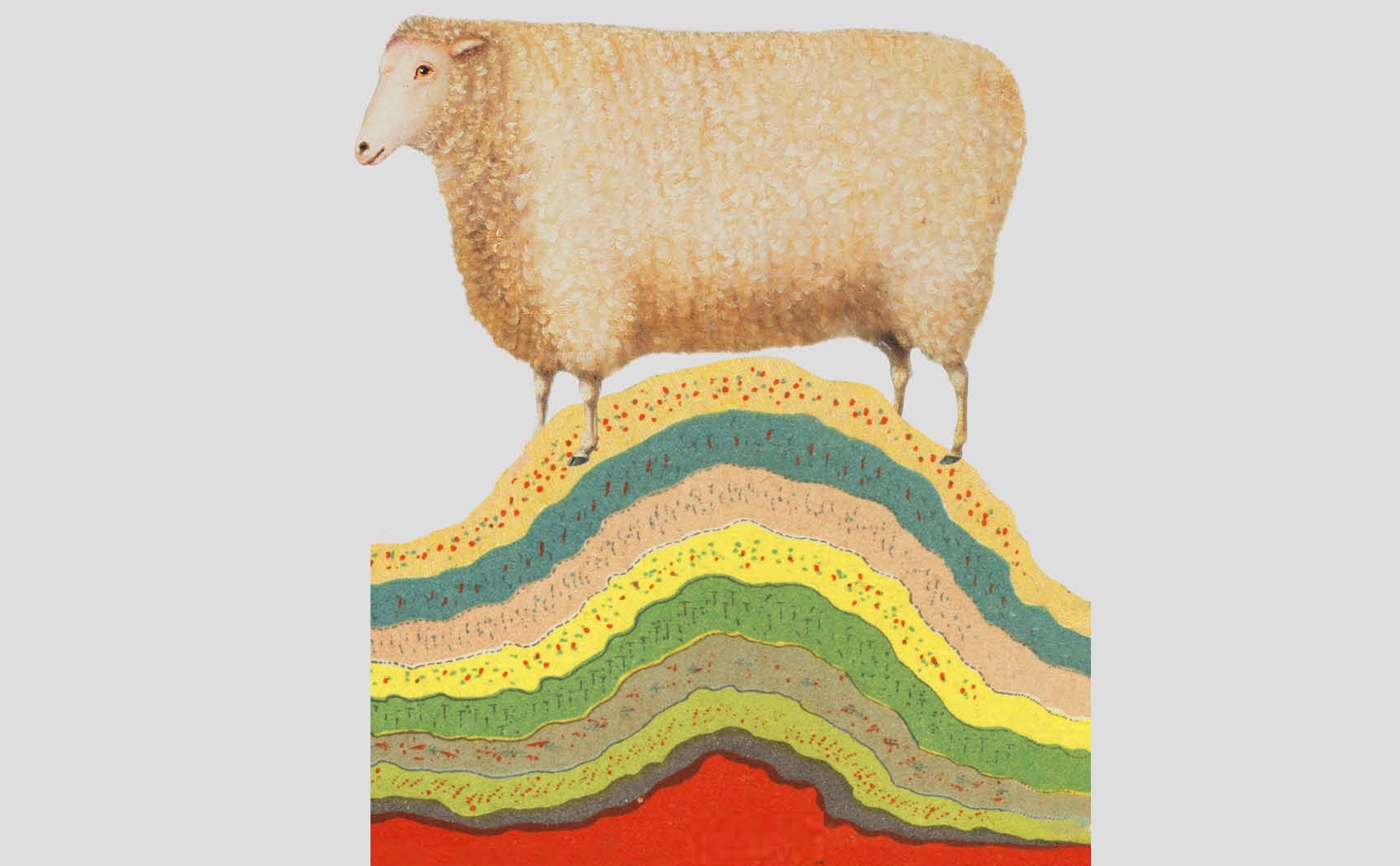

A similar moment occurs in the Irish author Caoilinn Hughes’ brilliant new novel The Alternatives when one of the characters comes across a sheep jammed in blackthorn shrub. “The poor thing was worn out from the ridicule of life… Rank stress wafted off the animal,” so she cut “it free from the last batch of thorns,” whereupon it immediately “bucked into another layer of them.”

The sheep—featured on the front cover as a stolid creature atop layers of surging earth—could easily be us humans and our everlasting eejitry. Some group of experts may yank us out a ditch—the white-coated folks at Moderna and Pfizer, let’s say—then, without so much as tossing a thanks their way, we barrel toward the next ditch, lowering our heads to take on momentum.

Four such people reaching down and yanking on our ankles are the Flattery sisters, the protagonists of Hughes’ third novel. Hughes is the author of the poetry collection Gathering Evidence and the novels Orchid & the Wasp and The Wild Laughter, all of which took home considerable hardware during their respective award seasons. Those first two novels followed lives thrown into turbulence because of the Celtic Tiger. The Alternatives probes a more gaping, self-inflicted wound: climate change.

“Flattery nostrils are a one and a zero,” one sister tells another. “Only the left sides of our brains get enough oxygen.” Rational and logical they are. Each in their thirties, they are all single, all have doctorates (one received hers honorarily), and all are, in their respective fields, doing work that addresses the conditions of the planet we are desecrating.

Rhona is a well-connected political science professor at Trinity College Dublin with “the conviction of a tennis ball launcher.” Maeve is a social media celebrity chef who is trying to get out of her book contract so she can publish the book her integrity demands of her—one that addresses future food shortages, shortages that Brexit has exacerbated. Nell, the youngest, also can’t be budged from her principled core. A philosophy adjunct professor in the United States, she stitches together the sparsest of livings so she can deliver, by way of example, a seminar on Heidegger’s care structure.

The three sisters are scattered across the English-speaking globe: Maeve in England, Nell in America, and Rhona—never for long—in Ireland. What brings them together is that their oldest sister, Olwen, a geology professor in Galway who can provide the receipts for why we are a doomed species, has gone missing. There is nothing necessarily nefarious about her disappearance. Long tethered and nagged by her “godforsaken undergraduates” and other responsibilities, she cuts herself loose by absconding in the middle of the semester and night when she goes “out to the garden to get rhubarb for her gin and [keeps] walking.”

She replants herself in the Irish countryside, and this is where her sisters eventually track her down. Together again, for the first time in years, the sisters exhume the bones scattered in their shared past, all with an eye on the dire prospects before life on this planet.

Reading The Alternatives, there’s the feeling that we’d all benefit if the sisters could conjoin into one like the Transformers used to at the end of each episode. They are, though, siblings, and siblings know every chink in the armor we wear out in the world. The sisters love each other deeply but also issue lines so cutting they could pierce organs. One or another is usually on the verge of Irish goodbye-ing the rest. Nothing lasts forever (though Olwen points out early on that “nature would have let us have a few millennia yet, if we’d been chill and sound and reasonable”), but for a little while the four sisters are together on the page, and what follows is a funny, intelligent, tenderhearted, and aching portrait—in the form of a play!—of siblings who were orphaned young and are trying their best to save us from ourselves. If they were to figure each other out along the way, that’d be a bonus.

Anyone who has read Hughes’ two previous novels can endorse this next statement: Hughes is one of the greatest writers of dialogue at work today. She is peerless in her ability to develop and communicate complex ideas through witty banter and possesses remarkable range in her ability to write across various points of view. Her sentences are to be relished.

These days, seeing in an author’s bio that they’re Irish is a bit like seeing Napa on a wine bottle’s label or Made in Italy stitched to a suit’s tag—you’re practically promised top-notch quality. Who knows what Ireland does with its mediocre talent. As for what gets out the door, Irish authors are producing some of the most exhilarating and audacious fiction in our times. The Alternatives is a perfect example of this. You never feel the author on the page, but every paragraph confirms this is the work of a dazzling talent, one greatly concerned about where we are and where we’re taking ourselves, but never allowing those weighty concerns to burden the prose or narrative or prevent her characters from having a laugh. During these uncertain and troubling times, we need more writers like Hughes who can, with such joy and resolve, stare down the barrel we’ve pointed at our heads.

Julian Zabalbeascoa: In several interviews for The Wild Laughter (which is one of my favorite novels of the past decade), you spoke about your possible next project centering around four sisters, and how you were resisting telling their story but were becoming convinced that you had to. Where did these four sisters come from? And why that initial resistance to writing what would become The Alternatives?

Caoilinn Hughes: The novel itself arrived first as four sisters, but I knew it would show them in their separate lives. I wondered about the magnets holding them together—besides love—when they’re living such different lives, in different countries, fighting separate battles, with their parents long dead, and while they’re each more invested in the present than the past. I wondered, as well, how those magnets would affect the women individually, in their separate lives. I was drawn to writing about women at work: women who center work in their lives and express themselves through their professions; women attempting to do meaningful or fulfilling work—work that gives them energy and anchorage and purpose. Taboo is too strong a word, but it’s still frowned upon for work to be the center of gravity of a woman’s life. (What counts as work is another question, like caregiving.) But I know so many women for whom this is the case. Also, I loved the idea that a book about sisters could also be a book about a geologist, a philosopher, a political scientist and a chef… walking into a bar! Family doesn’t only exist in a domestic realm.

JZ: Given Olwen’s motivations, I imagine most every interviewer will ask whether you have hope for the future or not. Meaning: do we still have time to solve the climate crisis or is our weight too far past the tipping point. So how, if at all, did the writing of this novel arm you with the hope and resolve you need to take on the direness of our circumstances?

CH: Yeah, wow, that’s a question! A huge one! Getting straight to the meat… or plant-based meat alternative! Let’s see. Writing this novel helped me to contend with being alive right now by spending time with characters who are attempting to the do the same, who are sitting forward, who have not clocked out—better people than me! Though, I’m never writing about heroes. This is the time we happen to be alive, and it’s no less worthy a time to be alive than any other, and therefore, it’s no less worthy of being represented in art. Even if we squirm at it, fearing its ugliness. Maybe what unites us is the way we think about the future—it’s just so different to how our parents thought about the future, and how it was thought of at any point in human history, given the existential crises we face. While our prospects and feelings and our practical plans about the future are far from homogenous, I do think something that carries across the world is a general pessimism about the future. So that’s something that might be new in its omnipresence. I’m interested in the ways that individuals deal with that species-wide phenomenon, which is rooted in environmental collapse, weakening democracies, the dehumanizing and siloing effects of ungoverned capitalism. And there are so many different ways to respond. In this novel, there are four characters, and while they don’t represent a spectrum, they do each respond differently. People might tend toward denial or despondence or despair. Or you can feel angst or guilt or shame. Rage is a common response. Maybe the more engaged you are, the more you realize that you might have to seek social support. Or foster community connections. Or you might be engaging in pro-environmental behaviors in your own life, or you might be engaging in change-making action. Maybe the fact that these sisters grew up without adults in the room primed them to be living in such a moment. They’re already familiar with the stages of grief. And in this case, the last stage can’t be acceptance. Grief is a big part of the novel, but it isn’t a grief that’s located in the past. This isn’t a novel about people dwelling on the past. It’s about the present moment, and so it’s less about what’s been lost and more about what’s being lost. Which I think is another way of talking about what’s not yet lost.

JZ: Sticking with this idea of pessimism. I’ve seen the toll our daunting prospects have had on my students. For the first time, many of them say they don’t have hope for the future. How does one convince them otherwise?

CH: In the last question you asked if I have hope or if we’re too far past the tipping point. What is too far past? I don’t think that’s an answer we’re waiting to get from scientists (though, of course, we’ve been given it) … It’s a question we have to ask ourselves, and to think about how our behavior would change if the answer is yes? Because it is yes! Of course we’ve reaped havoc. But does that mean we should just think: in for a penny in for a pound? Or is that an utterly immoral and inhumane mindset? I’d argue that it is. Your question here about how to convince others to have hope… this question on one level has to do with science communication and getting good information. There are conflicting studies about what galvanizes people, or what pushes them towards despair. The trajectory we’re currently on is a pessimistic trajectory, but that’s not to say there’s not another or many other trajectories we could be on. If you’re asking for my own feelings on this, I believe that we can have a much better world than we do now. I mean, there is and there’s going to be enormous suffering. That’s built into the emissions that are already in the atmosphere. So I think communicating the fact that more emissions equals more suffering is essential to helping people to understand that what we do now does matter. It really does matter because you’re affecting the suffering that will take place. Or you’re helping to pave the way for the better world that is feasible. Informing yourself is key. But I’ll run back into my wheelhouse now and say that to equip yourself emotionally and philosophically for what is to come, and for what is here… I believe that art has a huge part to play.

JZ: There’s a passage from the book: “It’s like with cows… you can taste the pre-slaughter adrenaline in the food if it’s come from a stressy, stratified kitchen.” If we extend the analogy a bit, this is the prevailing mood for the talk surrounding climate change. Understandably, even the best-case scenarios would inspire high stress and anxiety. But that’s not the case for The Alternatives. If I tallied the number of times I wrote “ha” in the margins, I’m sure it’d reach the triple digits. Why is it important to imbue the work with humor and joy?

I was drawn to writing about women who center work in their lives and express themselves through their professions.

CH: I think the best characteristic of the human species is our sense of humor. People might have different priorities. But for me, that’s the trait that makes us interesting and worthy of knowing, and beautiful and sexy and various. I love how much cultural difference there is in humor. And how even when we don’t speak one another’s language, you can find ways of sharing humor—it’s a shortcut, really, for understanding one another’s humanity. Also, as a reader, I just love funny books. Not necessarily comedies. I listen to this podcast every night, because I’m a terrible sleeper. It’s the only thing I can listen to—Kermode and Mayo’s Film Review podcast. Mark Kermode has this test for comedies: the six-laugh test. You need to laugh six times. But, I want that from all works of art, not just comedies. Otherwise, I don’t feel that the artwork is reflecting life as I know it. All day long, even in the bleakest of circumstances, you see people making small gestures towards making another person smile or laugh. I was writing the novel partly during Covid, and partly because of that and because of how challenging I found the novel to write, I wanted there to be some kind of joy on every page. There’s a really strong tradition in Ireland of the blackly comic, of tragicomedy. I grew up reading those works, so it feels quite a natural mode to lean into.

JZ: You mention you were writing during Covid. Did that effect your choice to set the novel in 2023?

CH: I was trying to set the novel in the year that it would be published. But the world is changing so rapidly. So in the process of writing it, I had to constantly anticipate what the coming years would be like, while trying to understand and capture the present moment as I wrote. That process reflected what the novel’s about, which is the attempt to lurch forward in the story as the rug is being pulled from beneath our feet.

JZ: In which ways did the book change – or did it change? – as you continued to incorporate our ever-shifting present?

CH: It changed a lot. I tried not to have too many cultural markers or seemingly temporary items from the news. There’s no Trump in the novel. Covid is maybe mentioned twice.

JZ: Brilliantly, with one of the sisters talking about a romantic drought as “the great abstention of 2020.”

CH: Yes, the realities of our times are in there! And in Rhona’s story—the political scientist character—her chapters were the ones I had to change the most… because UK and Irish politics were doing somersaults, it meant that the specific work I originally had her doing was becoming too chaotic and muddy. And I’m someone who writes in one draft. So for me to have to change anything substantive is a big deal, but it was part of the contract with a novel like this.

JZ: The characters in Orchid & the Wasp and The Wild Laughter try negotiating the turbulence of all that follows the Celtic Tiger. With The Alternatives it is climate change and, to a lesser degree, Brexit. These are right up there as the major self-inflicted wounds of our time. What is it about these structural forces that have greed as a galvanizing mechanism that so interest you as a storyteller?

Even in the bleakest of circumstances, you see people making small gestures towards making another person smile or laugh.

CH: And now I’m seeing the psychoanalytical red flags! It’s true, because Hart in The Wild Laughter sees himself as being a wronged person. But in terms of this book, I guess I’m drawn to writing about characters who are aware of the sword that’s in our belly, even if they don’t know what to do about it. Within their chosen professions, they’re trying to improve the world in some small way. They’re each contending with a different systemic challenge. The geologist is witnessing deep time collapsing—where processes that should be playing out over millennia are playing out over decades. Not to mention contending with a really frightened student cohort. The political scientist, Rhona, is working with weakening democracy. The philosopher is working within this degraded teaching system, and the commercialization of the Academy. And the chef is working within a volatile food system, related to climate change and geopolitics, and also the hot-blooded context of food nationalism. So they’re each on a path that’s being rapidly cut off. It’s important to note that they are all in privileged positions, where they’re able to pursue fulfilling work—work that they consider to be fulfilling—even if they might think differently about what makes for fulfilling work. So none of them think that they can pull out the proverbial sword, but they’re mindful of trying to do work that contributes to the world positively.

JZ: In The Wild Laughter, you illustrate the sort of self-flagellating the Irish were undertaking after the Celtic Tiger. To advocate for the Dark Prince for a moment, when it comes to climate change, our response to it, those of us who are environmentally conscious, might it appear the same? We’ve strayed on account of our excesses and only austerity can return us to a sustainable, natural state.

CH: Austerity is the wrong way to think about what needs to happen, in my view. That belongs to a neoliberal narrative. Take the case of food, since we have a chef character. There are so many new types of food. There are so many plants that we’ve never eaten, that we’ve never had the time or need or curiosity or incentive to pursue, partly because how animal farming is being subsidized. It doesn’t have to be a reduction of options. From a vegetarian perspective, going to a restaurant these days, you tend to have more than one option. So on a very basic level, it’s becoming more interesting to be vegetarian. So what does it mean to quit meat now? Is it just that you lose your choice? Or is it that you now have many more choices to eat well without causing serious injury? To walk outside through trees with birdsong instead of a nitrogen-noxious, bare, barren field. To have air to breathe that’s less polluted? Canals that aren’t rigid with algae? To live in a world where the consequences of what you do are less hurtful to someone else? To get to live well… to get to have mental health? That wouldn’t be austerity!

JZ: How did you arrive at the narrative voice and how did it allow you to tell this story, with four main characters? Most times it feels like a limited third, but it is more a roving subjectivity.

CH: I knew that this would be a polyphonic novel, and that the separate stories and voices would converge at some point. Olwen was my starting point—she’s why I wrote the novel. To me, she’s the central character, even though they’re all weighted equally. I do love the family gathering story. It’s really hard to pull off in fiction, but the challenge is irresistible. If you think of plays like Tracy Letts’ August: Osage County or films like Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen… You get to have all that complexity of the projection that goes on, the assumptions around family being together, and then of knowledge and history and blind spots. It’s much easier, I think, to put that complexity you get into a visual frame. But still, I think that some of the richest, thorniest, funniest works involving family gatherings have been novels. I will say, though, that while there’s that reunion sitting at the heart of the novel, I wanted to accommodate the fact that the sisters don’t define themselves in terms of family. They don’t see themselves as being fatalistically shaped by childhood experiences or parental expectations or guilt or dysfunctional role models or sibling rivalries. Anything like that. First and foremost, we see them in an extra-familial context. I hope that they’re still individuals, then, when they’re together. I tried to show how painful that can be—the struggle to hold onto ourselves around family. Our shared history can bring us together, but it can also trap us… because while that history might be shared, it’s likely to have been experienced very differently. With the point of view, to be true to each character, I tried to imbue the prose with the voice of that character. The word choices, the tempo, the frame, the sense of humor. It felt a little like writing four short stories to begin with—each with a distinctive tone.