Books & Culture

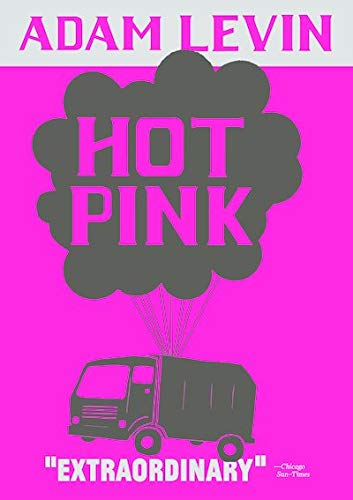

CELEBRITY BOOK REVIEW: Jonathan Franzen on Adam Levin’s “Hot Pink”

Editor’s note: Any resemblances to actual celebrities — alive or dead — are miraculously coincidental. Celebrity voices channeled by Courtney Maum.

In the vein of overt formal experimentation, Adam Levin’s short story collection, Hot Pink, reminds me of my childhood introduction to the branded breakfast cereal Froot Loops. Saccharine; excessive and ferociously colored, the pleasure one derives from reading Hot Pink is vivifying and caloric — the literary equivalent of a “sugar high.” Of the ten tales in this collection, I despised one; was indifferent to three; and found myself smiling through the other six: that is why I am giving this collection a positive review, and also why I have scheduled an X-ray computed topography of my cerebral cortex for next Tuesday.

As one unversed in the art of failure, I was terrifically bemused by Levin’s luckless characters. In “RSVP,” for example, the pathologically shy Donald pens “the world’s greatest love letter — four lines long, a mere seventy words” to the even shyer Janet, who, through a series of literal wrong turns, is promptly eradicated by a bus before receiving said letter. In “Scientific American,” — my favorite tale, I think — a hapless couple is rendered even more so by the appearance of a nihilistic gel oozing from their bedroom wall. When the nameless hero schedules an appointment with the builder for a time when neither he nor his wife can be present, this oversight causes him such overwhelming embarrassment, he comes to see himself as “a great imposition, not only on the builder but on his wife, the whole world.” Guilt, disorganization, disappointment, flailing — it’s fearful, the catalog of emotions experienced by people incompetent in life.

Another thing worth mentioning was the way in which Levin, subconsciously or not, both pointed to and perpetuated his generation’s disinterest in general erudition — in facts, truths, or principles of any kind. In “Jane Tell,” for example, our narrator informs us that he has accompanied his paramour (the eponymous Jane Tell) “to buy whatever part it was Tell thought she needed to replace to get her truck running.” In this excerpted sentence, their intellectual shortcomings are plainly on display: it is highly improbable that Jane Tell knows what part she needs, either, and if she happened to tell her boyfriend the name of the part earlier, well — he wasn’t listening. Whatever it is, whatever they need, whatever they lack can be “Googled;” back-ordered; Mapquested out. Long gone is the need to learn.

Levin’s metacognitive awareness of his generation’s intellectual slothfullness finally endeared me to his work. At one point, in the title story, upon seeing a garbage truck with a bouquet of multicolored balloons affixed to its grille, a character asks her companion if it is “some desperate form of graffiti.” I found myself wondering the same thing as I worked my way through Levin’s spastic, hyperactive, discordant prose. Has McSweeney’s merely provided Levin with a figurative tumbling mat for his verbal acrobatics, or is Hot Pink a serious examination of the various ways in which we fail to pay attention, and the desperation, disappointment and overriding sense of guilt that arises from neglect?

Electric Literature was unable to provide me with the fiscal motivation to pen my customary 12,397-word review, and so, I am going to prematurely conclude here by citing Adam Levin himself from “The Extra Mile.” “Our wives are all dead and we sit around warping. We can’t remember what made them laugh.”

Adam Levin’s Hot Pink made me laugh in two separate places — not out loud, mind you — but it was guttural, nonetheless. For this, I am grateful. Perhaps even moved.