Books & Culture

Chanelle Benz Is Rewriting History

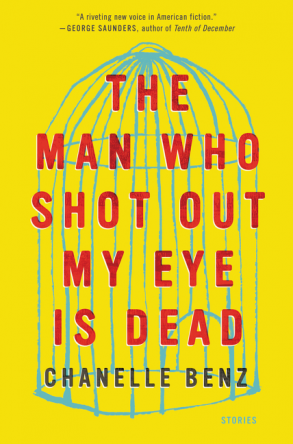

The author of the breakout collection ‘The Man Who Shot Out My Eye Is Dead’ on violence, voice and finding a place in classic genres

Finding a distinct voice is the first benchmark any great writer must accomplish. Chanelle Benz, author of The Man Who Shot Out My Eye Is Dead (Ecco), has created more than just a voice to stand out from the crowd. She’s created ten.

The stories in Benz’ debut collection are told from perspectives ranging from an eighteenth century slave to a baroque-style piece told in the collective We. The book begins with a non-traditional western that grabs the reader in close, then follows up with a contemporary story of family and violence that is just as gripping. It’s not just the wide-ranging eras and plots that make each story stand out; it’s the carefully-crafted voices. Benz is a trained actress who learned presentation is everything when it comes to captivating an audience and translated that skill into her writing. I recently spoke with her about how this collection came to be, how she found the voices, and people of color in the literary world.

Adam Vitcavage: It is easy for a short story collection fall into the trap of every story becoming redundant because the author wanted cohesion. Your collection is cohesive in tone, voice, and theme, but each story is so unique. How did you come up with such a wide variety of ideas?

Chanelle Benz: I initially set up an experiment for myself. What if I wrote a spy story? What if I wrote a post-apocalyptic story? What if I wrote a western? The first story I wrote was “Adela” — the second story in the collection — and I started doing that challenge. Things started to go awry. My version of a spy story was “The Diplomat’s Daughter,” which isn’t really a spy story; it’s more of an identity story. I just had a lot of fun doing it.

For me, part of it was trying to find a container for my story. It was healthy for me to set this experiment up. I guess the other cheat was that I was going to all of these periods of time that I’m interested in. When I was a woman growing up, and as a brown person, you’re not in historical movies or a lot of things. You have to insert yourself into it. If you want to be Billy the Kid or part of his posse you have to be his half-sister from some illegitimate fling.

“The Mourners” by Chanelle Benz

Adam Vitcavage: One thing I found very interesting about the collection were the distinct voices of each narrator. How did you hone in on all of the different characters and how they sounded?

Chanelle Benz: I used to be an actress. I came from mostly a theatre background where we did a lot of Shakespeare, the Jacobian dramas, so I think part of it was from my theatre background. When we were learning accents, we would learn phonetically, as well as sometimes by ear. But I could not get a handle on phonetics. I could just not understand it that way. What I could do with accents was give myself a key into it. It was some sort of sentence that I would repeat to myself over and over again until my tongue memorized the movement of the accent.

I think I must have done something similar with the writing. If I found a key into the voice I could find a way into the story. For the final story, “That We May All Be One Sheepfolde,” I read a lot of Thomas More’s letters and made lists of words to find my way into the cadence of that time without making it so far removed from what modern day readers would know.

Some voices come right away for me while others take a lot of work. “Adela” opened with the children’s voice. I wrote the first sentence and had to figure out where to go next. I added the scholar’s voice later. It just so happened that I was reading a lot of scholarly, post-Colonial essays at the time that I could pull some of that language.

Adam Vitcavage: Are there any examples that still stand out?

Chanelle Benz: I can’t think of any off of the top of my head because I made such long lists [of words]. I might end up dropping some of that, but I never came up with a single sentence. Just words I would try to insert into the story somehow.

Adam Vitcavage: You mentioned how growing up you weren’t really represented in movies and whatnot. How do you feel these time periods tie back into current events and how people of color are portrayed today?

Chanelle Benz: I think that it has a lot of resonance. When I set out to write [the stories], I wasn’t consciously thinking that I was going to write any political message. I think there were stories, like in “The Peculiar Narrative of the Remarkable Particulars in the Life of Orrinda Thomas,” Orrinda says something about it’s her crime to be two things: a brown woman. These two words “brown” and “woman.”

I feel that’s true today. There’s a punishment. You’re persecuted for just being. I don’t go around thinking of myself as as a brown woman. I just go around as me. It’s just the outside world that shows me I am these things and that there is a cost to that.

I don’t go around thinking of myself as as a brown woman. I just go around as me. It’s just the outside world that shows me I am these things and that there is a cost to that.

That’s true for a lot of my characters. There’s a cost to being who they are and how they were born into the world. I think that’s still true and that it’s probably going to get even more true.

Adam Vitcavage: I live in Arizona and a lot of my friends are of Mexican or Navajo descent and while I rarely think about it, hearing them talk about recent events, I try to connect, but as a white male I know I’ll never really understand. There are these outside persecutors telling us that we’re different in some way even though we aren’t.

Chanelle Benz: Because I’m brown and kind of lighter, that also carries a privilege, too. I haven’t had to put up with a lot of things other people have. I’m British and used to have an accent, so because of how I talked and looked, some of those things carry a privilege. I never experienced the things my friends might have because they were slightly browner or speak a different way. They’ve had to carry something different.

I think the things that are happening with Trump and the racial hatred that is coming out, for a lot of people in the black community or different communities of people of color, they’re not surprised. It’s not new to them. The news of police brutality is interesting because it’s not new. Not at all. The rest of us have just never had to deal with that on a daily basis.

It’s interesting because the things that other people had to deal with for so long while a huge majority of us haven’t are all of a sudden having to be dealt with by all of us.

Adam Vitcavage: Do you feel that — and I don’t want to use the word — but do you feel that there is a duty for people of color to express this through literature? Or what’s the place of literature in a climate like this?

Chanelle Benz: I don’t feel there is a duty. I definitely don’t feel like it’s people of color’s job to write about or even talk about these things. You know, I want the right to talk about dragons. I want the right to write about whatever.

I do think in a time like this and you’re an artist, you can be an activist, you can call your senator, you can be involved. But you’re a writer. It’s important. What I guess I would say is that you shouldn’t be afraid to alienate your fan base by standing up for your convictions. Don’t be afraid of putting something on Twitter because my Trump readers won’t buy my book.

All stories are about the human condition. That’s what all of the greatest stories do. They make all of the trappings of humanity transparent and they tap into that. I think that it’s important to not be shallow but to dig deep, whatever that means. It doesn’t need to mean be political. It just means to get at what it means to be human.

It doesn’t need to mean be political. It just means to get at what it means to be human.

Adam Vitcavage: Within this short story collection, a lot of it thematically deals with race, history, family, and violence. What drew you to these larger themes?

Chanelle Benz: Family is one of those things that you keep repeating. You just keep coming back to it. It’s a deep unresolved issue. As for violence, I just think we live in a violent world. In my own life I have had to deal with a certain amount of violence like I’m sure a lot of people have. It’s something that carries a certain charge and a certain stain. When you’re involved in an act of violence, especially taking someone’s life, you can’t undo it.

Peter Brook, who is an English theatre director, talks about Hamlet as this great moral dilemma to avenge his father and kill his uncle. But once he takes his life, his soul is stained forever. Brook talks about what it means to kill someone. On a certain level, violence is like that as well. Once you do violence on someone, it’s marked on their body forever. Mostly all of the characters in the collection have a choice where they can become involved in this or not.

Adam Vitcavage: Did you always plan on releasing these as a collection? I know some of them were published previously, but was that always the plan?

Chanelle Benz: Once I had two or three, I thought I had a collection. I probably thought I had 20 stories. There was a story that didn’t make it and “Recognition” was written right before the manuscript was final. I know the stories are very different, but I think there is a thread that binds them together.

Adam Vitcavage: I read an interview you did with Kit Frick in 2013 and you had the title of the collection then. Is that how long you knew this was a cohesive work?

Chanelle Benz: Yup. [laughs] The first story I wrote in around 2010 and I didn’t know it was a collection. I was working on a failed novel then. When I started writing stories I didn’t think of myself as a short story writer and I thought my novel was what I was going to finish. I was working with George Saunders around 2012 and the mechanics of the short story really clicked for me. That’s when I knew I could do it.

Adam Vitcavage: Out of the stories in the collection, which one proved to be the most difficult or had the most revisions?

Chanelle Benz: When I’m writing them, I think they’re all really hard. Definitely “The Diplomat’s Daughter” had the most revisions. I ended up with five versions of that. I had the one I liked, the one my agent liked, the one someone likes, you know? In the end the one we went with didn’t bother me. That’s what I like about short stories: I feel like you can totally have a few versions that go different ways and they’re all viable, unlike the novel. There doesn’t have to be a definitive one.

It was challenging to figure out the order [of the story]. I had to put myself inside of the reader. To me the story is very clear, but there are a lot of scenes and then there weren’t. It was a story that was very pulled back and I had to put a lot more in to lead the reader. I was hesitant to put the headers in there, but an editor at Granta was very helpful.

It was the kind of story that was like a deck of cards where I could keep adding scenes to it. It felt at times that there were turning points and different kinds of revelations. Actually, the version I put in Granta is different than the version in the book.

Adam Vitcavage: What about the easiest or most natural story?

Chanelle Benz: I think “West of the Known.” I’ve probably been writing that in my mind since sixth grade. It came out naturally — not perfectly; I had to change around a lot — but I can remember writing a lot of the scenes quickly and how it felt when I was going to write the bank robbery scene. I told myself to just do it and write a bad version of it first.

When [the character] Jackson came onto the page I instantly knew their relationship. It came so naturally.