essays

“Circe” Shows Us How Storytelling Is Power—And How That Power Can Be Seized

The latest book to give voice to the silent women of the canon, Madeline Miller’s novel subverts the masculine norms of epic adventure

Last year, British classicist Mary Beard published a slim book that aimed to chronicle how power, in Western civilization, has been set up from the very beginning to shut out women. The first example she gives in Women & Power is from The Odyssey: Telemachus only truly comes into his own as a man, she says, when he tells his mother Penelope that talking is men’s work. She dubs it Western literature’s “first recorded example of a man telling a woman to ‘shut up.’”

The first, maybe, but far from the last. The works that form the bedrock of our canons — Christianity, Western lit — often erase women by not allowing them to speak, or casting doubt on them when they do. At its heart, storytelling is a tool: from rewriting history books to having your press secretaries lie for you, shaping a narrative to suit your own ends is one of the most powerful cudgels an aspiring despot can wield.

But storytelling can subvert norms as well as establish them. That’s the grand, praiseworthy project of Madeline Miller’s new novel Circe: to take on the vast canonical text of The Odyssey, and the overpoweringly male world it describes, by telling the story from a woman’s perspective.

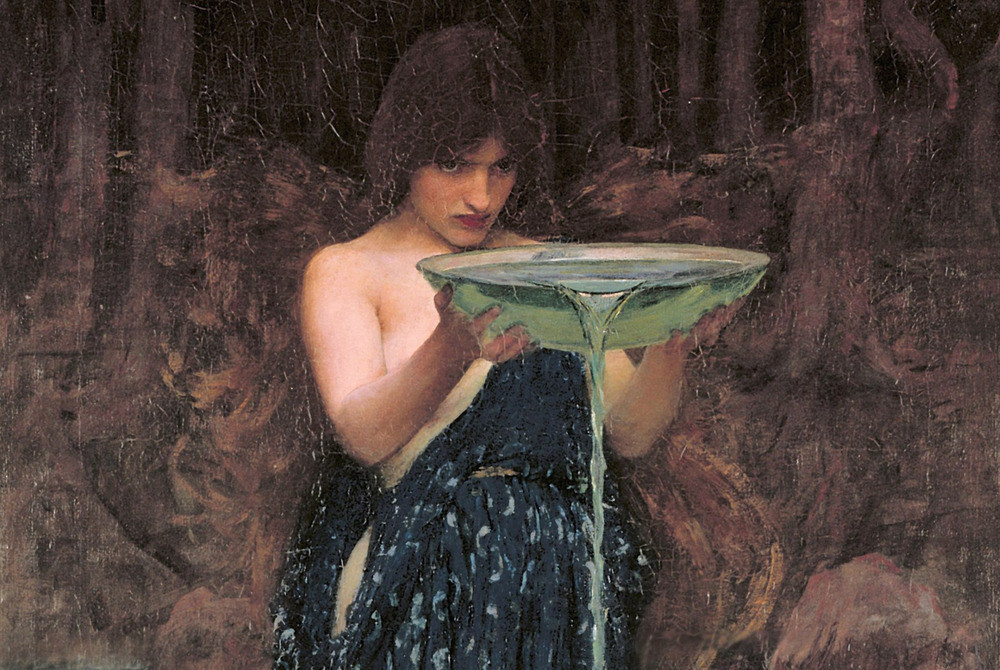

Even the bare sketches we get of Circe in The Odyssey already outline a potential feminist icon: a witchy woman who lives alone, turning men into pigs. Miller’s Circe, fully fleshed-out, is a towering, passionate figure whose life seems to be an unceasing stream of men failing her: Her brother Aeëtes, who she rears from birth, grows up and leaves to rule a kingdom without a backwards glance. Her father, the sun god Helios, literally burns her when she defies him. She falls in love with a humble mortal fisherman named Glaucos and turns him into a sea god; once changed, he promptly rejects her for the most attractive nymph he can find. When she’s eventually banished on some spurious charge to a small island named Aiaia, Circe finally disavows marriage, family, and all the trappings of confined female life. There are satisfying scenes in which she roams the island’s lush forests, defies a threatening (male) boar, summons a majestic (female) lion familiar, develops her witchcraft, and finally comes into her own. “Had I truly feared such creatures?” she thinks of her catty cousins. “Had I really spent ten thousand years ducking like a mouse?”

Much of the delight of reading Circe is recognizing just how many other Greek myths Circe finds her way into, informed by ancient texts or Miller’s own imaginings and woven into a coherent shape by Circe’s perspective. She’s the one who unintentionally transforms Scylla into the horrifying sea monster we know, the one whose six heads snap up Greek heroes from their ships. In a gnarly scene straight out of Breaking Dawn, Circe helps her cruel, beautiful sister Pasiphaë birth the Minotaur — and meets Daedalus and Icarus, before their fateful flight, on that same visit.

Of course, what really lends Circe’s narration that patina of lived experience are the many slights, great and small alike, of the men she encounters. She asks a sailor if she can borrow his cloak, and he greets the request with suspicion and defiance. (“I would come to know this type of man, jealous of his little power, to whom I was only a woman.”) She opens her home to a ragged crew of sailors, and when they discover that she lives alone, the captain rapes her. (“Brides, nymphs were called, but that is not really how the world saw us. We were an endless feast laid out upon a table, beautiful and renewing. And so very bad at getting away.”) When she casts a spell to look like her brother and speaks with a deep, commanding voice, all the men around her hop to attention. (“I almost wanted to laugh. I had never been given such deference in my life.”) Of course, you think, that’s how it would play out.

But since she’s embedded in this world, she also gets to see the legend-spinning in real time — and call out the bullshit as it gets made. One day, Jason of Golden Fleece fame and his wife Medea, Circe’s niece and also a witch, stop by Aiaia so Circe can ritually cleanse them of the various heinous crimes they’ve committed. Listening to Jason talk, Circe thinks, “I believed that he was a proper prince. He had the trick of speaking like one, rolling words like great boulders, lost in the details of his own legend.” In the ancient texts that are available to us, Jason’s own legend is the only one we have. But here, his story comes annotated with Circe’s irritated commentary, and Jason’s omissions — the casual but crucial omissions of motivated storytelling — become all the more glaring. “In his mind, he was already telling the tale to his court, to wide-eyed nobles and fainting maidens,” she notes, pointedly. “He did not thank Medea for her aid; he scarcely looked at her. As if a demigoddess saving him at every turn was only his due.” That’s the story of the Argonautica, but it’s not the story of Circe.

Since she’s embedded in this world, Circe gets to see the legend-spinning in real time — and call out the bullshit as it gets made.

Years after the events in Circe, Circe hears a rendition of The Odyssey more familiar to us, and she is not impressed. “Humbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets,” she says. “As if there can be no story unless we crawl and weep.” In one widely-read modern translation, Odysseus rushes her with his sword — no Freud needed — and “she screamed, slid under my blade, hugged my knees with a flood of warm tears and a burst of winging words:…‘You have a mind in you no magic can enchant!’” and then propositions him in the same breath. Within the context of the novel, it’s Circe who has the authority to say what really happened; she knows what the truth is because she was actually there. Outside of the book, there’s no “really” or “actually” or “there”; the events of The Odyssey are fiction. But Circe’s authority is as good as Odysseus’s. She just needed the chance to speak.

Madeline Miller is not the first to give voice to the silent women of the canon. More than a decade before Circe, Margaret Atwood produced The Penelopiad after finding Homer’s original wanting. “The story as told in The Odyssey doesn’t hold water: there are too many inconsistencies,” she wrote in the novel’s introduction. “What was Penelope really up to?” And Jean Rhys’ 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea explores the backstory of Jane Eyre’s madwoman in the attic, raised in the West Indies and married to Mr. Rochester in Jamaica. Rhys, herself a white woman from Dominica, greatly respected Charlotte Brontë. But, as she wrote to an editor, “I…was vexed at her portrait of the ‘paper tiger’ lunatic, the all wrong creole [sic] scenes, and above all by the real cruelty of Mr. Rochester.” In another correspondence she simply wrote, “That unfortunate death of a Creole! I’m fighting mad to write her story.”

These texts are correctives, reparations; they exist to address injustices in the world of literature. (Think also of the recent trend of nonfiction that highlights the unheralded but pivotal roles women played in scientific advancements.) People who were formerly cut off from the story-making apparatus, who were not allowed to matter to the story — because of gender, but also because of class and other ways of being on the margins — now shape the narrative. This is true not only of the central heroines, but of more minor characters who were also shuffled aside. Both adaptations of The Odyssey, for instance, make much of the hanging of the maids — the 40-odd lines in book 22 where Odysseus and Telemachus round up the servant girls who slept with (or were forced to sleep with) Penelope’s suitors, and kill them for “rutting on the sly.” In The Penelopiad, Penelope’s narration is interspersed with songs and skits from the maids, who act as a “chorus line” (like a Greek chorus, but, well, you get it). In the end, Penelope says she deserves the blame for their deaths, but the maids haunt Odysseus in the underworld for eternity, and they get the last words in the book. In Circe, Telemachus himself claims that he will be tormented by the image of their twitching feet for the rest of his life.

People who were formerly cut off from the story-making apparatus now shape the narrative.

There’s something gutsy about revising a story already enshrined in a canon, because canonical stories somehow feel truer, whether it’s the Star Wars canon, Harry Potter, or the O.G. Christian canon. They have more authority because they were written first, everyone recognizes those stories, and anyway, all retellings owe their existence to the originals.

But this embroidering of stories, changing the parts that seem off or lame, is an old, old tradition. “Except for dull encyclopedias and stories told on grandmothers’ knees, there was no such thing as a ‘straight’ version of Greek myth, even in antiquity,” Mary Beard wrote in her review of The Penelopiad in 2005. “Every literary telling we have is already a reworking, a prequel, a sequel or a subversion, which then (as so clearly with The Iliad and The Odyssey) becomes ripe for reworking itself.” This is a different model of power in storytelling: not canon/non-canon or authorized/unauthorized, but something more diffuse, where power is wielded by individual storytellers and authority constantly shifts.

But read Circe, The Penelopiad, and Wide Sargasso Sea together, and you’ll notice striking differences between Circe and the other two books — differences that I think outline two distinct ways of thinking about how women can claim power through stories. The older works change the form of the story, from the thrusting male hero’s journey to more traditionally “feminine” narratives. Circe, by contrast, merely snatches up the hero’s role and lays claim to it, just as it stands.

Circe, as a character, already has power, even within Homer’s world; the other two protagonists lack it completely. True, all three of them — Circe, Penelope, Antoinette — have absent and/or awful mothers, lonely childhoods, and cloistered adult lives (an island, a palace, the drafty attic of Thornfield Hall). But unlike Circe, a goddess who has personal autonomy, independence, and the power of witchcraft, Penelope and Antoinette are bound to men. Penelope’s story involves an arranged marriage and hordes of suitors occupying her home and eating her food at will; all of her attempts to control her fate must be executed in secret — like unraveling the shroud she’s weaving in the dead of night. She’s only speaking out “now” in The Penelopiad, thousands of years after the fact, because she’s safely in the underworld and “all the others have run out of air.” And Wide Sargasso Sea is basically a chronicle of Antoinette’s inexorable sidelining — from an arranged marriage (yes, her too) to her husband’s growing mistrust and hatred of her, and finally, in Part Three of the book, her imprisonment in England and her own madness. In those two books, the women’s only source of power comes from the fact that their stories are being told at all — not, as with Circe, because within those stories they do mighty things.

The older works change the form of the story to more traditionally ‘feminine’ narratives. Circe merely snatches up the hero’s role and lays claim to it.

Just take the language in Circe, which is elevated, arch, formal, chock full of strong adjectives — it draws on the stylings of epic poetry, and thus seizes the power of the epic for itself. Each sentence of Circe’s lofty narration puts her at a remove from us humble modern readers. It’s a constant reminder that she’s larger than life, different and greater than your average human: “The stink and weight of blood hung still upon me, and at last I found a pool, cold and clear, fed by icy melt. I welcomed the shock of its waters, their clean, scouring pain. I worked those small rites of purification which all gods know.” The dialogue, too, feels labored and inflated. “Be welcome,” Circe tells one character; “Let me not see you again,” she tells another. Her father terms her “worst of my children, faded and broken, whom I cannot pay a husband to take.” No one actually talks like that — but the fact that they do in this story lends everything an archaic, and implicitly powerful, sheen. Everything about the way the story’s told, in fact, focuses so intently on playing up Circe’s momentousness that the stakes take on a certain teenagery melodrama: “[Odysseus] showed me his scars, and in return he let me pretend that I had none.” Legends as a general rule are not subtle — and Circe, which resembles a legend far more than it does a novel, isn’t either.

Contrast that with Atwood’s aggressively casual Penelope. She starts explaining the context of her betrothal to Odysseus, then goes off on a tangent about “an overdose of god-sex,” and then suddenly returns to the topic. “Where was I? Oh yes. Marriages.” We hear about her horticultural tastes as she strolls through the underworld’s fields of asphodel: “I would have preferred a few hyacinths, at least, and would a sprinkling of crocuses have been too much to expect?” And Penelope is savvy about 21st-century life: she snarks about the use of steroids in athletic competitions and the fact that we worship “flat, illuminated surfaces that serve as domestic shrines.” Her relationship with Helen, her famously beautiful cousin, is positively petty. The Penelopiad punctures the loftiness of its epic forebear with the promise of real talk; its concern isn’t to spin a legend about people who are larger than life but to point out just how disappointingly life-like those people actually are. Compared to the strained grandness of Circe, it’s a relief.

Then there’s the fact that The Penelopiad and Wide Sargasso Sea are both polyphonic works — their structures accommodate multiple perspectives. The man Antoinette marries (Rochester, though he’s unnamed in the book) narrates much of the novel’s second section — in it, we hear about his own growing alienation, and we feel sympathy towards him even as we note his prejudices and injustices towards Antoinette. “There is always the other side, always,” Antoinette tells him — but Rhys might as well be speaking directly to her readers. And the maids in The Penelopiad break up Penelope’s more linear narration with a whole range of forms, from a jump rope rhyme to an anthropology lecture. Jarring and a little hokey they might be (though the sea shanty is excellent), they put a fine point on the fact that every story has a side that hasn’t been told, that narratives are never monolithic.

This all seems to me strikingly similar to Mary Beard’s suggestion of what exactly to do about this problem of women and (lack of) power. Instead of thinking about power as “the individual charisma of so-called ‘leadership,’” and attempting to fit women into a system that’s already “coded as male,” she says, we should redefine what power is. To her, that means “decoupling it from public prestige…thinking collaboratively, about the power of followers not just of leaders.” Something that’s democratic, inclusive, residing in many voices. Just think of the #MeToo movement, which has been built from the unified voices of a tide of heroic but often-unnamed women.

Circe does not fall into this vein. It doesn’t aim to tear down the whole edifice; instead, it seeks to claim its power for itself, and, by proxy, womanhood. Circe’s perspective throughout the book is unbroken, the story runs chronologically straight, there’s nothing so radical or destabilizing as redefining the nature of power itself. The Odyssey is basically a book about one man’s deeds and adventures; Circe is the same, but about a woman. Even the sizes of the books on my desk are drastically different. Neither Wide Sargasso Sea nor The Penelopiad break 200 pages; my shiny, embossed copy of Circe, nearly twice as long, looks much more imposing next to them.

Circe doesn’t aim to tear down the whole edifice; instead, it seeks to claim its power for itself, and, by proxy, womanhood.

Obviously, I’m ambivalent about this book. Burn it all down like Antoinette! I want to cry. But I think we do benefit from reclaiming history, especially an imagined one (those are much more potent), as long as we also make room for other, more subversive expressions of power. And there’s delight to be had in showing your truth unapologetically. While Penelope schemes in secret and Antoinette drugs her husband in a last-ditch attempt to win him back, Circe asserts herself directly. “You do not know what I can do,” she tells a threatening god; when she defies her father, she says, “I will do as I please, and when you count your children, leave me out.” Rallying cries are unifying, after all.

So this question of women, speech and power. Should we try to cultivate a different, more diffuse kind of power, as The Penelopiad, Wide Sargasso Sea, and Mary Beard suggest? Or should we take on traditional notions of power and make them our own? The answer, I think, is yes.