interviews

How Do We Reckon With the Art of Problematic Artists?

Claire Dederer’s "Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma" provides no easy answers to whether we can separate the art from the artist

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma offers no easy answers when considering the art of wrongdoers. Across thirteen chapters, Dederer unpacks the complex legacies of a variety of artists—Woody Allen, Roman Polanski, J.K. Rowling, Picasso, Michael Jackson, and many more—with unfailing wit and nuance. Threaded throughout this exploration of genius, creation, and monstrosity is her own history as a consumer, student, critic, mother, and writer in her own right. As Dederer openly wrestles with questions of fandom and morality, Monsters serves as an undeniable reminder that our biographies are inextricable from our experience of the art we love.

Monsters provides a roadmap for readers who are interested in thinking through the subtleties of Dederer’s questions and willing to sit with the resulting discomfort. “The way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person, or a good one,” she writes. “You’ll have to find some other way to accomplish that.” As Dederer’s own biography shapes her considerations of capitalism, criticism, and time itself, Monsters offers a deeply personal testament of one fan’s multifaceted relationship to the art of imperfect people.

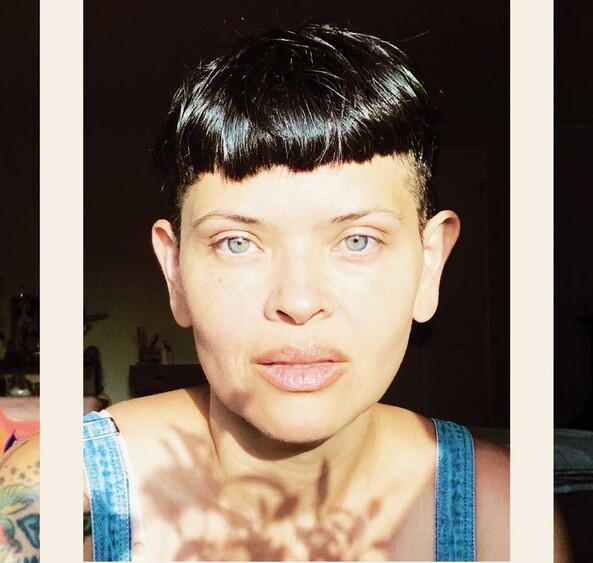

I spoke with Dederer over Zoom about her experience of going viral, fame’s relationship to art, and the thorny intersections of capitalism and love.

Abigail Oswald: How did the viral response to your Paris Review essay “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?” feed into the way you crafted Monsters?

Claire Dederer: Every writer knows that having a viral piece is both a dream and a nightmare. Here’s the deal with that piece, I wrote this book called Love and Trouble about predation of young women—girls, really—in the 1970s, and a theme of the book was sort of “What is it like to be an adult who had that experience, and how did it affect my sexuality?” And in that book I really engaged with Roman Polanski. He’s used in the book as a kind of straw man, and also as kind of a person I’m in dialogue with. So by the time I’d finished that book, I really knew everything there was to know about Roman Polanski’s rape of the young girl, and yet I was still watching the films. So I started writing Monsters, I’m gonna say in 2016. And just really sitting with this question of what is happening when I consume this work. What do I feel like? What’s my experience of it? How does my idea of him alter me as an audience member?

So that essay was never conceived as an essay. It was always conceived as the first chapter of the book. I had really approached the subject with curiosity, without an axe to grind, without something I was trying to prove, but with this very exploratory mindset, and I think that’s why the essay did well. I think it was because it was nuanced, and the nuance didn’t come from me being some genius, the nuance came simply from the fact that it was something I’ve been working on for years. But it looked like it was in response to the moment, and so for me that was a really interesting experience—almost more as a citizen than as an artist myself—because it was really heartening, actually, to have something in the current information economy that was super nuanced and had a really strong positive response, right. I don’t mean to be Pollyanna-ish or like, bright side of miserable topic, but that made me feel both excited about my work, but also excited that there was a potential for a more complex dialogue. And so that was my initial response.

Then I had this experience of the ways in which there were feminists who had a problem with the essay. There was a response that was like, don’t totalize these kinds of offenses. And I was like, well, clearly I didn’t make that point clearly enough. So that was great, I could take that on board and think about it for the final book, which, as you’ve seen, I feel like I’ve wrestled with it. And there was just this constant barrage of Woody Allen defenders and men’s rights people and accounts being set up to attack me. Which speaks to my larger point, which is there’s something about our subjective emotional collapse with this work that is undeniable and profound, which I saw in all these accounts being set up to attack me.

So, as I proceeded working on the book, [I was guided by] the knowledge that nuance and a really deep exploration was going to be my watchword. It took me five years to write the book.

AO: Part of the modern rise in this conversation about the artist’s biography can be attributed to changes in media consumption and the sheer contemporary accessibility of said biography. How would you say the more widespread accessibility of biography has affected our sense of responsibility as consumers?

CD: One of the central ideas of the book is the idea that we don’t strive for biography, it happens to us. That biography is like an ongoing natural disaster—just befalls us, right? And that we don’t really get to choose that. So in terms of how I personally approach knowing things about the people whose art I consume, I feel like choice is not part of it. It just happens. The plight of the audience member, as I see it in this book and as I explore it in this book, is this person to whom the knowledge has already happened. So then, what do you do with it?

What effect do I think that has on our experience of art? I think that the answer to that is, first of all, taking a step back and saying it does have an effect on our experience of art. The initial question that sort of comes up over and over—or used to, I think it’s slightly more nuanced now—is “Can you separate the art from the artist?” And that’s one of the first principal questions this book asks. And because I believe that biography befalls us, and because I believe we can’t pull out our response to the biography, I think the decision to separate is a flawed decision. It’s a failure before it begins. I think my first response is that we respond with that biography on our minds, whether we want to or not. And then the question for the audience is what do you do with that knowledge? Do you acknowledge it and consume the work anyway? Do you not watch the work because it’s too painful? Do you not watch the work because you’re making an ethical stand? And I think there’s as many answers to that question as there are viewers, readers, listeners…

AO: You write at length about the difficulties women encounter in their efforts to make art, even touching on your own personal feelings: “When I do the writing that needs to be done, I sometimes feel like a terrible mother.” Monsters is primarily about men, but you do discuss a few women—Anne Sexton, for example, whose daughter detailed their fraught relationship in her memoir, Searching for Mercy Street. Can you talk more about how you considered women’s relationship to monsterhood while working on this book?

The idea of what is unforgivable in a woman isn’t a sin of commission—it isn’t an action—but it’s a sin of omission.

CD: So one of the early things I do in the book is start to interrogate this word “monsters.”…I sort of move through this idea of the monster and then explore the idea of “the stain,” which is this inevitable coloration of our experience of the work—which to me is more interesting, because I like how it suggests the inevitability, and I also like that it sort of has less name-calling to it. It’s just, this thing has happened. And so I was thinking about what the stain is for women. And when I explored it and really thought about it, it had to do with abandoning children.

So I explored this idea of abandoning children through the lens of several female artists, and what became so fascinating to me about it was the fact that the notion is a continuum, right. I write in the book about how I went away on a fellowship and I was thinking about like, well, how long do I stay at this fellowship before I’m abandoning my teenage child, right? I was gone for five weeks, which was a very long time for me. And so that experience of being away and living that distance really brought home to me this idea that there’s no set answer, right? And then that notion of abandonment gets refracted in several different ways, you know? It’s like, Sylvia Plath killing herself and locking the door against her children is a kind of abandonment as a mother. Would her story feel the same if she was not a mother? Or Doris Lessing leaving two of her children behind in Africa, or Joni Mitchell giving a child up for adoption. These are all life choices that don’t bear necessarily, don’t deserve the word monstrosity, but they color our view. And it just seemed like the idea of what is unforgivable in a woman isn’t a sin of commission—it isn’t an action—but it’s a sin of omission, where you fail to nurture. And as somebody who is a mother and feels like I’m never quite—my kids are grown, and it’s like, am I doing enough? I feel that to this day…

AO: In your writing on Hemingway, you explore the idea that he might have felt trapped, even tormented by his performance of masculinity. There’s this idea that some artists who reach a certain level of celebrity begin to feel hemmed in by their public persona, or otherwise responsible for maintaining a certain audience perception. Were some of the artists you discuss acting out in an attempt to fight that public image, while others’ bad behavior was an attempt to reinforce it?

CD: I think it’s less of a monstrous question than a problem of great fame and great success. Anytime you have such a successful image… What do you do with it? I think a really creative genius, a really great artist, will figure out a way to continue to make their work. But they’ll have to either decide not to engage with the persona, or bring the persona into play, right? And I think that’s part of, you know, Woody Allen at his greatest is engaging with his own persona, right? I mean, I think that in Stardust Memories he does that hilariously. I think that sense of play about it is really interesting. And I think someone like Hemingway, obviously he was trying to play with it in The Garden of Eden—I mean, maybe not even consciously—but he’s undermining some idea about his own masculinity. But maybe if you’re that masculine of a man in a culture that venerates masculinity so powerfully—maybe it’s a dead-end street, you know? Maybe it’s harder to get out. Whereas Woody Allen, you know, his persona was one that was other, right? He’s the weakling, the kid—there’s so much about that that was other as he was coming up. And then I think there’s also brilliant artists who just do everything in their power to not engage with their persona and stay out of it.