Books & Culture

Colm Tóibín’s ‘Brooklyn’ and the Art of Adaptation

What it means to bring a book to film

When English professor Kevin Griffith and his eleven-year-old son Sebastian uploaded pictures from their work Brickjest — a Lego toy adaptation in the form of discrete dioramas, each representing a scene from David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest — their collaborative project quickly went viral. In the articles that followed the focus was not on their fealty to Wallace’s text but, in part, on their ability to make us consider what it means for textual characters to become tactile and occupy a physical space, in an age of adaptations when such characters increasingly seem to be stepping off the page and becoming fodder for digital screens.

In an instance where an adaptation represents such a radical act of transformation, the resulting conversation seems to work both ways, to also look at the new meanings that might be found in the source text because of this other, highly divergent form in which it now exists. But when it comes to cinematic adaptions the criticism still tends to work in only one direction, obsessed with the adaptation’s fidelity to its source.

For a long time film was — and perhaps still is — considered not to be on equal footing with other forms of art. The filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, explaining the abundant presence of other art forms in his work (the music of Bach, paintings by Bruegel, his own father Arseny Tarkovsky’s poetry), suggested that because cinema was relatively young, the presence of older art forms lent it a temporal weight, and an authority that would cement its place among the arts. That not much has changed in the status of cinema-as-art over the years––as if film were perpetually young––is most apparent when it comes to adaptations, about which one invariably hears that the book was better than the film. It’s this sort of default reaction that even avid film buffs seem conditioned to believe, a statement sometimes made before due reflection. It is only partly thanks to a subliminal belief that literature is the superior form of art; the other part of it comes from the light in which critical conversations about adaptations actually take place.

In his book Concepts in Film Theory, the renowned film critic Dudley Andrew proposed three models that, in total, describe the ways in which a screenplay can draw from its source. When a film borrows from another text, the source doesn’t necessarily share a storyline with the resulting work — it merely serves to inform the film’s subtext and essential emotion. In Abbas Kiarostami’s film Shirin (2008), for example, an audience — composed almost entirely of women — sits watching a film based on the tragic Persian romance “Khosrow and Shirin.” We only ever see the women’s faces and never the film they’re watching, which exists solely for us as an aural presence: an amalgam of dialogue, song, and dramatic sound effects. (Incidentally, these were added in editing; Kiarostami filmed each of his actors individually in his living room, a blinking light falling on their faces to simulate the effect of being in a movie theater). But the knowledge that the film these women are watching is a classic romantic tragedy inevitably informs the way we read their expressions.

The second of Andrew’s adaptation models describes films that intersect with their source text, in which a text is preserved wholesale when rendered into cinematic form. In Ritwik Ghatak’s 1961 film about the aftermath of the Indian partition, Komal Gandhar (“A Soft Note on a Sharp Scale”), a group of East Bengal migrant artists find themselves stuck on the wrong side of the border. On the one hand we see the characters preparing to stage a classic Bengali play, and on the other we get to see the play itself as it’s performed. The abrupt shift between these two registers proves to be a clever formal device, recreating the displacement being experienced by the characters themselves.

The most common form of adaptation Andrew calls transportation, in which the cinematic version retains the essence of its source text. Among many contemporary examples is the 2015 film Brooklyn (John Crowley). Based on the book by Colm Tóibín, and adapted by the novelist Nick Hornsby, Brooklyn the film makes significant departures from its novelistic source. The first third of the book, approaching sixty pages, shows the central character, Eilis Lacey, at home in Enniscorthy, Ireland. She lands a job at the town’s provisions store, run by Miss “Nettles” Kelly, then moves into the room of one of her brothers. In the film, Eilis (played by Saoirse Ronan) boards the New York-bound ship about ten minutes in, her time in Ireland occupying less than one-tenth of the movie’s total running time.

Among other things, the book intends to critique the Ireland of that time period (the 1950s), which had little to offer the young, compelling them to make Westbound oceanic journeys in search of better prospects. The film’s predominant concern is to focus on Eilis’s more positive experience after moving to the New World. Her less than ideal Irish work life is captured in a three-minute long scene, her personal life — she has no one to date! — reduced to and represented by a single dance room scene, which lasts only two minutes. Both of these scenes serve a metonymic function, allowing the audience to infer an accumulation of other moments similar to these that have led Eilis to make the decision to leave.

While Eilis in the book is possessed of three brothers and a sister, in the film these characters are collapsed into a single sister, Rose (Fiona Glascott), after whose death Eilis comes back to Ireland. In both texts the factor keeping Eilis from returning to Brooklyn — the fact that her mother will now be alone — gives rise to a central question: should Eilis choose her homeland, or the new home she’s made for herself in Brooklyn? Hornby’s thoughtful choice increases the stakes of the narrative in the film, less giving way to more.

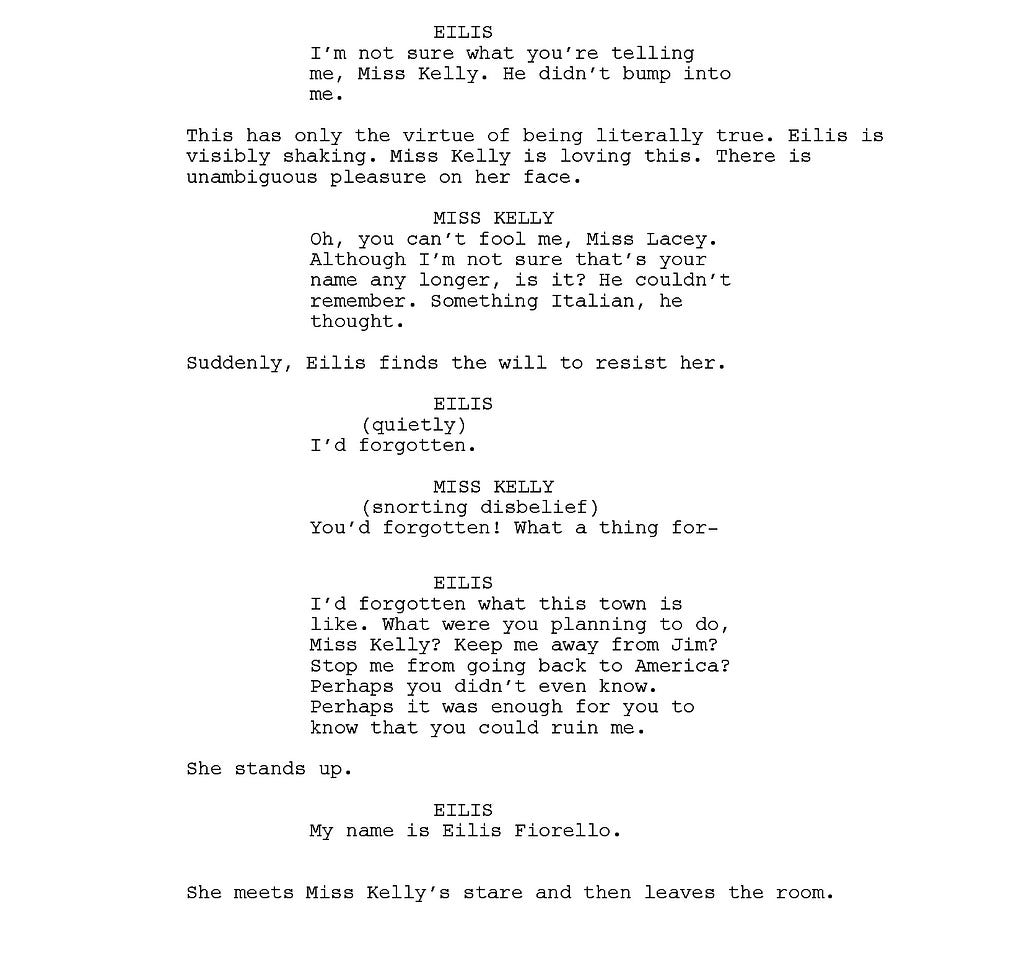

Most notably, however, it is a vital scene towards the end of the film that proves to be a significant departure from Tóibín’s novel. Unexpectedly making roots in Ireland after her return — this time she has a reputable job, and a love interest, Jim Farrell (Domhnall Gleeson) fixing to marry her — Eilis’s former employer Miss Kelly (Bríd Brennan) confronts her with the procured knowledge that Eilis is already secretly married to someone in America, a man named Tony Fiorello (Emory Cohen). In the book Eilis responds to this indictment with fear, and decides once again to leave Ireland. The film gives Eilis more agency in her decision to leave: she stands up to Miss Kelly, critical of her small-minded nature — and, by extension, that of others in the town, where everyone appears overly concerned with everyone else’s business.

Here is the scene as it appears in Tóibín’s novel:

In her tone, Eilis tried to equal Miss Kelly’s air of disdain.

“Oh, don’t try and fool me!” Miss Kelly said. “You can fool most people, but you can’t fool me.”

“I am sure I would not like to fool anyone,” Eilis said.

“Is that right, Miss Lacey? If that’s what your name is now.”

“What do you mean?”

“She told me the whole thing. The world, as the man says, is a very small place.”

Eilis knew from the gloating expression on Miss Kelly’s face that she herself had not been able to disguise her alarm. A shiver went through her … She stood up. “Is that all you have to say, Miss Kelly?”

“It is, but I’ll be phoning Madge again and I’ll tell her I met you. How is your mother?”

“She’s very well, Miss Kelly.”

Eilis was shaking.

“I saw you after that Byrne one’s wedding getting into the car with Jim Farrell. Your mother looked well …”

“She’ll be glad to hear that,” Eilis said.

“Oh, now, I’m sure,” Miss Kelly replied.

“So is that all, Miss Kelly?”

“It is,” Miss Kelly said and smiled grimly at her as she stood up. “Except don’t forget your umbrella.”

And the same scene in Hornby’s adapted screenplay:

The intention of both the book and film is to show Eilis’s character arc. But in the film Eilis’s response to Miss Kelly is a consequence of her change, while in the book the scene triggers a change in her.

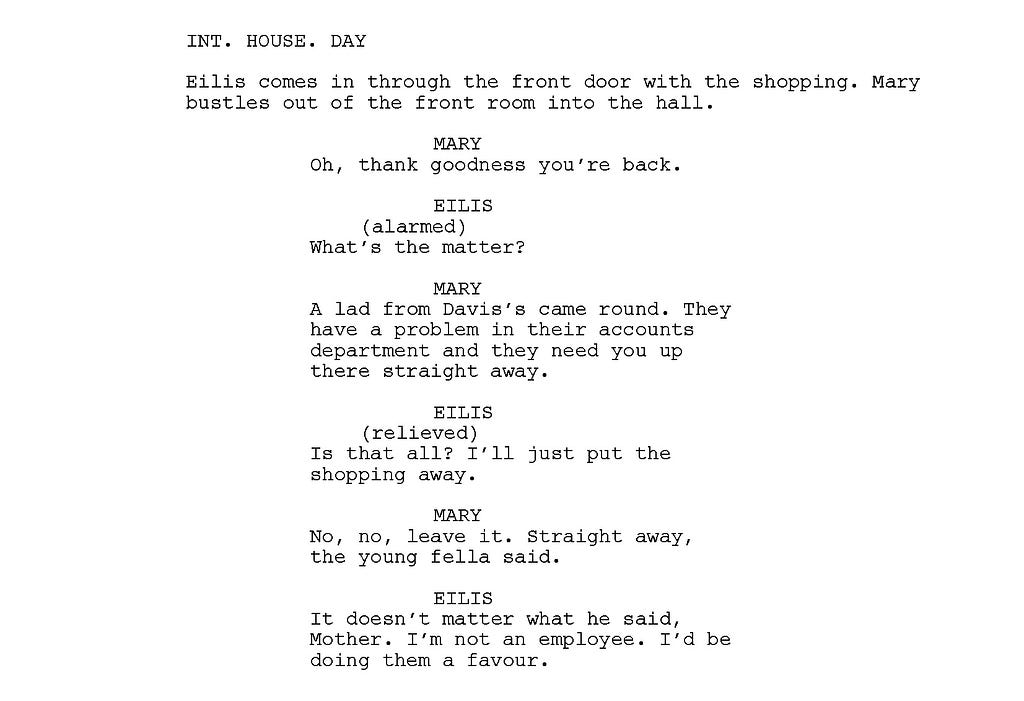

The cinematic narrative spends a lot of time showing Eilis gaining validation in Brooklyn — receiving acceptance and friendship in the boarding house where she resides, achieving fulfilment at work and in college, finding love. “Think like an American,” urged a woman who befriended her on the ship from Ireland. In one particular scene, following Eilis’s confrontation with Miss Kelly, we see how living in America has shaped her:

Eilis shows her understanding that she has the choice to not honor what’s being asked of her. In this light, the depiction of Eilis standing her ground against Miss Kelly — whom she’d been intimidated by at the beginning of the film — can be seen as an actualization of her sense of self, constructed over time while living away in Brooklyn.

Tóibín concludes her arc through precisely crafted and meticulously paced sentences, in which Eilis reflects on her decision to return to Brooklyn, moving from fear to a certainty that the path she’s chosen serves her interests best. The moment of this realization comes in the book’s final paragraph, as Eilis once again leaves her hometown:

“She has gone back to Brooklyn,” her mother would [tell Jim Farrell]. And, as the train rolled past Macmine Bridge on its way towards Wexford, Eilis imagined the years ahead, when these words would come to mean less and less to the man who heard them and would come to mean more and more to herself. She almost smiled at the thought of it, then closed her eyes and tried to imagine nothing more.

Where the book uses interiority, the film relies on dialogue and image, thereby changing the texture of the moment that completes Eilis’s arc. The final paragraphs of the book contain a litany of Irish landmarks and towns, while the film shows Eilis wordlessly reuniting with her husband Tony, the iconic Brooklyn Bridge evident in the background. In discussing his adaptation process, Hornby (quoting Michael Ondaatje) suggests that a good film adaptation finds the short story within the novel, serving to underscore both the economy needed for a film’s brief runtime, as well as the audience’s capacity to measure change in a character across the tight temporal framework of a film.

The author Joseph Conrad wrote that “the power of the written word … is, before all, to make you see,” a sentiment almost exactly echoed by filmmaker D.W. Griffith, when he suggested that his purpose was “[a]bove all … to make you see.” An obvious difference between books and films is in the way they promote seeing. Whereas books conjure up mental images, the filmic image has a quality of given-ness to it. But another, less frequently discussed point of comparison is made manifest in Conrad’s and Griffith’s twin statements, not in the word “see” but from another shared word––you, the intended audience. And it is this ‘you’ that should be the kernel of all discussions concerning adaptations.

The choices by which Brooklyn the film departed from its literary counterpart were meant to etch a particular version of Eilis in the minds of viewers, within the tight timeframe of a film. Komal Gandhar staged a play inside a film in order for the audience to gain a better grasp of the experience of displacement. When it comes to discussing adaptations in general, the focus should be on their fidelity to the audience, rather than to the source text. The audience remains the focal point when a screenwriter reshapes their source text with the intention of bringing it to the screen — to bring it from one kind of readership to just another kind of viewership.