interviews

Colonial Violence and an Old Prophecy Haunt a Chinese Family Across Generations and Continents

Alice Evelyn Yang on the challenge of seeing your parents as people and the role of folklore in her debut novel, “A Beast Slinks Toward Beijing”

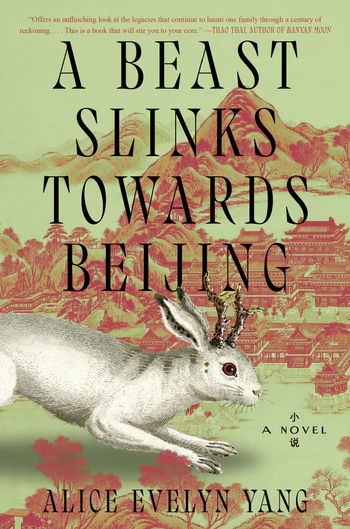

Alice Evelyn Yang’s sweeping debut novel, A Beast Slinks Toward Beijing, chronicles the experiences of a Qianze, a second-generation Chinese-American, whose estranged father reappears in her life a decade after leaving her and her mother. What follows is a whirlwind tale of Qianze’s lineage, spanning 93 years and two continents, tracing back through her father Weihong’s childhood during the Cultural Revolution in China to his mother Ming’s experience during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. Shifting between these three perspectives, Yang not only chronicles the events that preceded and precipitated Weihong’s abandonment of his family, but also illustrates the magnetic power of stories and secrets as they accrue over generations, wielding the power to bring people together and repel them apart for reasons that seem inexplicable.

Through lush imagery, other-worldly creatures, and breath-taking attention to detail, A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing mimics the form of the story within. Under Yang’s precise and delicate pen, a family’s decades-long web of well-intentioned avoidance and experiences of colonial violence unceremoniously unravel as a drunk and confused Weihong attempts to reveal a prophecy from his past in his daughter’s Chinatown apartment. Careening between time periods and dimensions, the novel’s central characters are tied together not only by shared history and DNA but a deep-seated sense of anger and fear that transmutates into an empathy that cuts across time and space, revealing untrodden paths forward. Much like the accumulated weight of Ming, Weihong, and Qianze’s inherited trauma, A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing is all-consuming and impossible to put down until every last stone is overturned.

I had the pleasure of speaking to Yang in her Brooklyn apartment a week before her debut’s release about the blurred lines between predator and prey; folklore as a force of and against imperialism; and seeing one’s parents as complex, flawed humans.

Christ: I found A Beast Slinks Towards Beijing to be about the power of stories themselves. Was that the conception of the book?

Alice Evelyn Yang: I began the book by writing the initial reunion scenes between Qianze and her father. After I had this seed of an idea, I wrote the book chronologically. I first wrote Ming’s timeline, then Weihong’s, and then the present-day sections. I always knew that there was this frame-tale that would wrap around the story. My idea for structure has always been a Russian nesting doll where each generation carries the previous generation within it. I want to use stories as a way to interrogate how people share societal values and how myths and folklore are representations of patriarchy and the fears of a certain society.

C: So much in the book is about what happens when stories aren’t told. It’s understandable when parents want to save their children the unpleasant details of their past, but what do they risk when creating a vacuum like that?

It is possible to not follow down the path of your parents and grandparents.

AEY: I grew up in a first-generation immigrant household where my parents weren’t very forthcoming with their past or Chinese history at all. The bulk of what I learned about the Cultural Revolution I had researched on my own. Like Qianze’s mother, they thought, “Oh this is a new life, we are going to leave the past all behind.” The book poses the question of how do you reckon with trauma when it’s made physically manifest? A lot of the risks in not learning your familial history are things that are encoded genetically from intergenerational trauma. For Qianze, it’s physically-manifested unspoken trauma but also the trauma of colonialism and empire. The things that are happening to her she has no understanding of. You’re left in the dark scrambling, looking for answers, and the answers might be right in front of you, but you don’t have access to them.

C: Qianze, Ming, and Weihong all share experiences that lead to a bifurcation of the self. Is this exacerbated by their patchy understandings of their own personal histories?

AEY: The situations they were placed in forced them to have this sense of themselves as a before and after. They can’t conceive of themselves as a whole being in which before and after are reconciled. The events that split them, they hold so central to their sense of identity that there’s no way to make peace with them. They can’t let these wounds heal; they have to keep picking at them and taking the scab off. So it becomes this part of themselves that is so core to their identity.

C: As Ming and Weihong live through the Japanese occupation and the Cultural Revolution, respectively, the amount of political violence is staggering. How do you think that is reflected or refracted in Qianze’s timeline and her experience in the US?

AEY: A lot of people around me who are also second generation immigrants are learning about the Cultural Revolution through my book, despite their parents living through it. For Qianze and for myself, we live in a relatively privileged time, especially because we live in the imperial core. We’re insulated from what is going on outside of the West, neo-colonialism, and empire. If you don’t even have the knowledge of the effects of colonialism and empire, and it’s not actively taught in schools in the West, you can’t understand what’s happening right now in the Global South. Qianze lives this very privileged life where she doesn’t know about her family’s past, but at the same time the atrocities that happened in her family’s past are still ongoing in the present. It offers a window into empathy for and understanding of what atrocities happened in the past, but also what atrocities are ongoing in the present.

C: That sense of perpetuality comes throughout the book: that these things that have happened, are happening now, and will always be happening. How does this shape the arc of these characters?

AEY: I had to piece the timelines together like a patchwork quilt. I was looking for these tissues of connectivity between them to find where each generation echoed one another. Placing them in similar situations or placing the same objects throughout these generations, there is that sense of continuity, but also that they are speaking to one another. There are parallels between them, so even though Ming and Qianze never meet, Ming still somehow communicates with her, which is done through the folklore and magical realism elements. With the idea of a self-fulfilling prophecy, these characters find themselves in loops and a few of them can’t seem to break out. What I wanted to suggest in the ending is that it is possible to not follow down the path of your parents and grandparents, and you can find healing and move on from these cycles that feel inescapable.

C: There is a recurring metamorphosis of prey becoming predator, most obviously embodied by the hare becoming the jackalope. How does that figure come to represent the experiences and fears of the book’s central characters?

Anger is this nexus of transformation from prey to predator.

AEY: One of the primary emotions I am working with is anger and how transformative anger can be. Qianze is such an angry character and that anger has transformed her. Like you said, the bifurcation of her: The Qianze before Ba, who she sees as having this idyllic, happy childhood, versus the Qianze after Ba who’s forced into this position that she sees as unjust. She had to take on a very adult role from a young age. Anger is this nexus of transformation from prey to predator. At the same time, I want to challenge the notion of who is prey and who is predator. I never want to create a dynamic that is so black and white, because there is so much ambiguity. A lot of the characters that commit the most violent acts in the book, whose actions feel very predatory, you also understand the reasoning behind those actions and how, in certain circumstances, they were forced into committing those actions. Just because something or someone shifts from prey to predator doesn’t necessarily make them more powerful.

C: You do such a wonderful job of weaving passages of surrealism into what is a deeply realistic, human, and historically accurate story. Could you speak on where the magic of the story originates?

AEY: I studied magical realism in university in the context of Latin American literature: works by Gabriel García Márquez or Jorge Borges, Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo, Kingdom of this World by Alejo Carpentier. In those cases, a lot of folklore and magical realism is within a narrative of colonialism. There is this traditional folklore that sort of works as a force against colonialism. I wanted to examine that idea as what happens when a colonizing force that uses folklore is also colonizing the land? That’s where Japanese folklore creeps in and intrudes into the family. You have a foreign colonizing force’s demons and monsters, but you also have traditional folklore like the hare with horns, which in its simplest form is a metaphor for intergenerational trauma. My editor asked, “What makes this family special that they have this hare with horns?” This family isn’t special. I found the hare with horns in a book of omens and prophecies with hundreds of creatures. It could be any family or any creature. The idea of the magical part where it follows them and haunts them doesn’t mean that they’re chosen in any way. In fact, there are probably all these other families with different omens following them.

C: So many of the mythological or folktale figures during Ming and Weihong’s youth are women. Why is that?

AEY: There are a lot of allusions to female monsters and demons in both Japanese and Chinese folklore: fox demons, the Yamauba, which are old mountain hags in Japanese folklore. All of these portrayals go back to this idea of monster theory, where folklore conceives of monsters as fears of a certain society. The village in rural China was so afraid of women deviating from the norm, of being anything but a chaste wife and mother. Even when someone is forcibly driven off that track, they are vilified and demonized. It’s a deeper understanding of how these monsters were created and how maybe they weren’t monsters at all, but a reflection of the values that this village had.

A lot of what is considered monstrous is justified anger or emotion. Ming is seen as monstrous by the village because she is healing from something that they can’t understand, but they know that she no longer shares the values that they hold dear. Conversely, the Oni commander in the Japanese army is basically the most evil character, but when you think of someone who’s immortal, they have a completely different perspective of the world. There is complexity to him because he is envious of death. He isn’t meant to be a pure black-and-white figure. There is a sense he favors Ming because there is this distorted sense of connection between them.

C: Despite him being the most evil character throughout the book, it’s made clear that the worst violence in the world is committed by humans. How does that ground the story?

AEY: There are these supernatural elements of monsters and demons, but at the same time, that’s a story that we tell in order to justify the actions that humans have taken to survive. Qianze says, “If I was backed up in a corner, would I have committed the same moral failings as my father?” Looking at memoirs of the Cultural Revolution, it’s likely. We all want to think that we’re better, but when we’re pushed into situations that come between our survival and our family’s survival, people can easily do monstrous acts. The harder thing is to stand by your morals.

C: Food is very central to Chinese culture and the family unit throughout the book. How do you see food or the lack thereof operating across the book’s different timelines?

People can easily do monstrous acts. The harder thing is to stand by your morals.

AEY: I come from a privileged background, so I can never imagine what famine feels like: food as luxury, food as a driving force to make someone do these unforgivable actions. During the Red Guard ransacks, they would take the food. So food is this reward that’s won. During the Japanese occupation, the Japanese army plundered Manchuria for their goods. In the present timeline, it’s very different. Food becomes this language of care. Qianze and Weihong have a hard time expressing their complicated feelings towards each other, but you see how she makes the steamed egg custard, which is something he made for her. These unspoken gestures show how the connection between them still exists.

With all the motifs and symbols that keep on occurring in the novel, they have to change with time. It’s interesting to see how these same symbols appear in each generation, but they have completely different meanings.

C: In that same vein, the color red plays a pronounced role throughout the book.

AEY: Red is one of those symbols that accrues different meanings because it appears in all these different contexts. Part is the history of the Cultural Revolution. People were split up into this idea of red or black. You also have motifs: the red thread that is Weihong’s leading line into his past. He follows what he sees as a red thread of fate through the maze of his memory to find the memories that he feels are most important. The Cultural Revolution was so dominated by these colors of red, and I want it to have different meanings and complexity. In traditional Chinese culture, red is a very lucky color, and it’s something you wear for Chinese New Year and weddings. The color has such significance in the culture, it’s bound to have multiple meanings and the same is true in the book. It means fate and fortune, the communist regime and the violence that is committed because blood is red, and there’s a lot of blood spilling within this novel. Nothing is ever good or bad; it’s got multiple dimensions to it.

C: In the last part of the novel, each of these three characters have moments of keen understanding of one or both of their parents. How are those insights necessary for rebuilding their own self-image?

AEY: Ming was so vilified by the people around her who she considered part of her home [that] she understood more intimately the role of women in this society. That gave her access to understanding her mother and her conceptions of her mom as monstrous, which is not to say that her mother wasn’t a bad parent. She understands now how someone can become that angry and bitter because she’s gone through events that have created those emotions in her. That is a parallel experience with both Weihong for Ming and Qianze for Weihong: Understanding their parent’s past and what actions shaped them makes them more human. If you just know someone blindly without knowing their context, it’s easy to vilify them, but knowing [that] what happened to them and what they did didn’t occur in a vacuum lends itself to understanding them more as people.

C: What is so hard about getting to the place where you can see your parents as people and not just parents?

AEY: This is something my friends and I have dealt with. When you’re a child, you don’t have the maturity to see your parents as fully-fledged people beyond them being your caretakers. I’m 27 now, and I remember when my mom told me that she was 27 when she immigrated to North America. That was really jarring to me because I always felt her past was this mythological thing, but then I imagined myself in her place. When you’re a child, you tend to idolize your parents and it erases the flaws, and humanity comes from the flaws. Qianze is having trouble reckoning with this idealized vision of her father, who abruptly left, with the very human person he is now. Writing this book for me was trying to put myself into the skin of someone who lived through the times that [these characters] lived through.

[Like] a lot of second-generation children, I used to feel so frustrated with my parents that they hadn’t fully assimilated, because when you’re a child, being different feels so glaring, and I just wanted them to be like every other parent. I remember being frustrated when they would talk in Chinese in public. I have a lot of regret for how I acted then. I also don’t think I knew better, but now that I’m an adult, I just want to understand them as people, and I want to give them all the grace that they deserve.