interviews

There’s More Than One Kind of Loneliness

Courtney’s Sender’s "In Other Lifetimes All I've Lost Comes Back to Me" examines feminist millennial rage and Jewish American inheritance

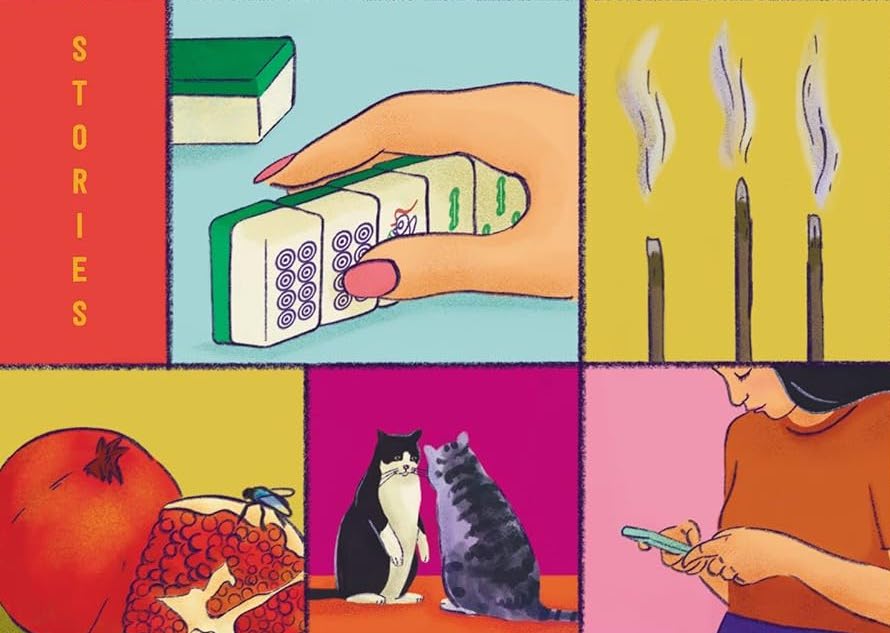

A profound and deeply funny examination of loneliness in many of its forms—romantic, familial, artistic—Courtney Sender’s book, In Other Lifetimes All I’ve Lost Comes Back to Me, explores feminist millennial rage and the ways the trauma of the Holocaust has been passed-down through Jewish American families. Sender’s debut collection of linked short stories uses magic, myth, and divine intervention as well as a sophisticated three-part structure to create the sense of a narrative more unified than a classic short story collection often achieves.

I spoke with Courtney Sender in person on an unseasonably warm spring day in a classroom at Connecticut College, where Sender is Visiting Assistant Professor of Fiction. We discussed the role of the spiritual in fiction, how story collections might do better justice to the knotted experience of being lonely in love than a novel, and how making a reader laugh creates an embodied response that’s essential to the impact of the sad things that come next.

Emma Copley Eisenberg: Tell me about longing and return in this book.

Courtney Sender: Most of the stories in the first half of the book have some kind of sequel or match in the second, I was in a place in my life where I had experienced some longed-for returns. The book’s title breaks into three parts, which are kind of the three parts of the book and the three themes of the books. So it’s the “in other lifetime,” the “all I’ve lost,” and the “comes back to me.” So the the first part is about longing and the last part is about return. If you live long enough, certain desires you put out into the world do come to you—and the ones that you deeply want don’t, of course. And for some of them it’s too late or you’ve changed too much. So I was really interested in what happens when the thing you long to come back does come back, but by the time it does there’s a question of whether it’s wanted anymore. Longing is in some ways very simple. Like you just want the thing. You can’t get it. Getting the thing you long for is much more complicated. In other words the getting can be more complex than the longing.

ECE: How is the book approaching loneliness?

CE: The characters in this book are struggling with being alone and not having romantic love. In a novel that’s struggling with that problem, your character winds up either alone or with someone.

I don’t subscribe to the idea that if you’re alone and you’re not happy about it, then you have some self work to do.

You can have a foil character or a second main character who winds up the other way, you can have the protagonist get love and then lose it, you can have them imagine what it would be like to go the other way, but ultimately the narrative of your main character is that they are alone or they are not alone. And that just did not feel good enough for what I was trying to do. I did not want to privilege any of the potential options because loneliness has been the great struggle of my own life and the resolution to it, the medicine for it, is sometimes someone else coming back and sometimes finding you don’t want anyone else at all. And both of those are really valid.

I don’t subscribe to the idea that if you’re alone and you’re not happy about it, then you have some self work to do. I don’t think humans are meant to be alone, but I also think there’s something very beautiful about being truly comfortable and whole by yourself. So I just didn’t want to privilege either of these in a book, and that’s why I ultimately had to make it a collection.

ECE: What does the spiritual mean to you?

CS: Openness to not knowing. I went to divinity school, and that’s what I took out of it the most. In my stories, the characters are feeling this unbearable accumulation of loss and that the things that they wanted don’t exist in this timeline, and that the desired outcome must, it must exist somewhere else.

So they turn to something bigger than themselves, something that can see the longed-for other lives, and to me that’s kind of a God question. I’m Jewish, but I don’t mean any particular religion’s God. I mean: in the throes of a certain extreme longing for a life that you simply cannot have, because the path to it has already been foreclosed, you’re seeking anything for comfort and solace. But you’re also seeking anything to blame. And I think that God, the characters’ own personal conceptions of God, can be both of those things.

An example: my story “Epistles” has a tongue-in-cheek God giving the character a note that says basically, sorry, I forgot to make you a soul mate, my bad. And the character winds up rejecting the idea that he has no soul mate. So maybe that note was God in the first place, but maybe it was the character being like, why am I so alone?

In other words, maybe God was created from the character as the epitome of a pure howl, a pure longing, a pure desire. Those emotions feel so much bigger than ourselves.. I think that’s when we go to a God, a thing that can contain the bigness of those feelings in ways that we cannot.

ECE: No particular religious point of view is assumed in the book. It’s just like another level of meaning that the characters can bring to their experience or not, depending on the story. But bringing in the Holocaust element, does that feel like the “all I’ve lost”? There’s a lot of intergenerational stuff that the characters can’t quite name, which from reading some of your essays and knowing a little bit about your family makes a lot of sense. How did you understand the role of that intergenerational stuff?

CS: The Holocaust to me is very linked to the question of which lines get cut off and which remain. My grandparents on my father’s side were survivors. So like, I am a line that didn’t get cut off. That was my grandmother’s conception of it too—essentially the other lines got chopped and shouldn’t have. So maybe I’m giving voice to those other phantom lines. I see the Holocaust elements as the “in other lifetimes.”

When you make someone laugh, their belly is exposed and then you can stab them with the harsh thing afterwards.

I think that some of my characters feel a very strong burden and responsibility from being in this line of the living. They feel the presence of the souls that were all set to come into the world, but the people who were meant to be their parents died in Auschwitz instead. The characters are picturing those ghosts in the world. The characters are haunted by the dead, so they recognize how lucky they are, that they get to be in the line of the living. And I think there’s a recognition of that. No matter how bad things get for my characters—and things get bad—they are glad to be alive.

But it’s also a massive responsibility to be carrying the dead. I think the characters are often speaking with those other voices in their minds, that the conversation with those ghosts becomes part of their own consciousness.

ECE: I also found this book to be very funny. For a book that you’re describing as a lot about loneliness, I just want readers to know that it’s very funny. So, how do you approach humor?

CS: It’s all sort of hilarious to me. Like when things get so dark, there’s a humor to it. And maybe that’s a defense mechanism, right? Because what is humor? It’s distance, basically. Up close, many things are pure trauma or tragedy but if you go distant enough, there’s humor. It’s funny to imagine my dad’s ancestors from the Holocaust being like, oh poor you, you’re lonely. We’re dead.

So the humor in the book is part psychology, a coping mechanism; and part recognition of the truth that everything is most palpable with its shadow-self around the corner. This idea is right there in the language of the belly laugh, right? When you make someone laugh, their belly is exposed and then you can stab them with the harsh thing afterwards. Laughter is vulnerable. You’re laughing together, and then you get in there with the knife that says, like, and here’s the serious side of it.

ECE: Did you think about emotional modulations as you move through the collection? Like, did you want readers to feel a certain way in each of the three sections? And this is also a selfish question because I’m going to be putting together a short story collection, how did you think about the order of the stories?

CS: A lot of this book comes from deep empathy for people who are lonely. I spent a lot of my life very lonely in ways that seemed like this unsolvable problem. These stories are a real expression of what people do in response to that sadness, so if I’m putting something like this out into the world, I think it’s my responsibility to offer some light out of that darkness, too.

So I thought a lot about: where does hope come into it? And to me, like, there’s two big places where hope happens in the book. One is the story “An Angel on Stilts,” which ends with aspirations to belief in goodness. It’s a hope ending. And then immediately afterward, the next story is in the concentration camps.

That was a really intentional choice because it’s exactly like the laughter, the big openness of hope. Like your body is open to hope and then it’s the stab of the camp.

And the stories after that are questioning what is the function of hope. One of the characters explicitly says, Nana said that hope is not what got her through the camps. And just morally, ethically, with various friends I’ve had who essentially lost hope that life can be different—I think it’s important to recognize that it’s not just hope that keeps us going. The book thinks it’s life. Just life alone is a blessing, even when it’s when it’s a curse.

ECE: I love that. It kind of reminds me of Angels in America: “more life.”

CS: Yes, more life. More. Yes. That’s where hope is.

ECE: And where do you feel like that leaves the characters with their longing and their loneliness?

CS: The last line of the book is: believe, believe, believe. Like kadosh, kadosh, kadosh. It’s said three times, like magic. It’s an incantation. Maybe the narrator doesn’t fully believe it. If you truly believed it, you could just say it once. But they want to believe it. It’s a wanting for belief, a longing for belief.

ECE: All of us are millennial writers because we are millennial humans, but there’s certainly, I think, longing around permanence and stability and around a sense of home in here for me. Do you feel like the concerns of labor and millennials were important for you here?

CS: Oh, totally. I feel like I was promised a certain version of feminism, which had really noble aspirations but has proved disappointing. The idea that we can “have it all”—the domestic, the romantic, the reproductive, the creative, the professional, the financial—belies that each of these things is profoundly difficult labor and all of them at once is maybe impossible. I’ve become especially sensitive lately to the financial side, the fact that “spouse or parents” is basically the answer to the question of how a lot of artists and writers are affording good lives.

All this to me is very similar to the promise, spoken or unspoken, that you’ll find love, it’ll work out. We recognize that some people will not find love, some people will want it and not get it. But like, it’s not going to be you. Like you’ll be fine. And that’s what society has said to us writ large–capitalism, feminism, the ziggurat structure of a publishing career, all these things have difficulties, but we’ll just push them off and it’ll be fine and we won’t have to hear from those for whom it wasn’t fine. And I think a lot of people our age are feeling like the promises that we were fed are just not what’s coming to pass. And for my characters, this is all playing out on a very personal, interpersonal, small level, in their love lives.

ECE: For me, that’s another “all I’ve lost” in here. In addition to all those losses that you described, I did feel the sense in your book of just like, institutions are not to be trusted and institutions are crumbling. How should a person be now is another subtitle of this book.

CS: Yes. For many of the characters who have a Holocaust background, that’s an event that very strongly told the characters no, you can’t trust authority. Civility can crumble in a moment. I don’t think that’s the American ethos that I grew up with, though it did feel like the ethos I picked up from my grandmother’s experiences.

ECE: Is there anything that does feel solid for your characters?

CS: Life is a blessing. That is solid for my characters. Not that life is easy or enjoyable, or happy or without suffering, but it’s a blessing regardless of how bad things get. I couldn’t really write this book until I was able to enter a headspace where I felt solid in that, too.