essays

Crucifixion: Nathalie Handal on Being Palestinian, Writing and Enduring Love

We’ve asked some of our favorite international authors to write about literary communities and cultures around the globe. We’re bringing you their essays in a new series: The Writing Life Around the World. The next installment is by the poet and playwright, Nathalie Handal.

I sit by the window and wait for her to finish her story. She has the posture of a ballerina. Her honey-colored eyes against her hot magenta headscarf offer a striking contrast. We are on a bus at the Bethlehem checkpoint en route to Jerusalem. The anthology of Arabic verse I’m carrying inspired the exchange. She tells me that each time she enters Damascus Gate she recreates the day that changed her forever. Then adds that she has eleven versions so far. I don’t know what she is speaking about and for a second the sky’s paleness distracts us.

She explains: I memorize. I’m addicted to memorizing. I memorize the exact pitch in the voice of the kaak seller, the gleam in my sister’s eyes when she meets the sun by the window, the circumference of the circular window. I memorize Al-Mutanabbi. I just memorized the face in the red Toyota Corolla that passed by us. I memorize street numbers, abandoned neckties, books. I memorize him. His charcoal eyes. His full lips. Square chin. White teeth. I forget him. I keep re-memorizing him. Together we wrote poetry. Threw the fear in the mountains we never could get to.

I forget he memorized with me. Once we memorized Jabra Ibrahim Jabra’s work, and as we started Ghassan Kanafani’s stories, the half-moon insisted we memorize it first. We were happy in our craziness. We ached. I memorize the way my hands get cold and my heart beats aimlessly as if it’s broken. I forget I remember him. And his Lifta. Forget the rain caught in the yellow light of night. I forget the pen he gave to me. The one I left with him so that he could keep giving it to me each time we met. I forget I never saw him again. Forget why he didn’t memorize the world and stayed with me — a strange soul who memorizes to keep the empty rooms in every blank page of my notebook away.

I just memorized the twenty-three cars that passed by us since we started this bus ride. I won’t bore you with their colors or the expressions on their faces. I’m not speaking of the drivers or passengers. The faces beneath the faces. Everyone here is a grave. And a pulse.

Once we get to Damascus Gate, I will begin a new version. I will forget the version when I walked by the vendor selling grape leaves and radios, dates and multi-cultured spices. When the merchandise dangling above was like the colorful pages of books of all sizes, when two girls were playing with their ponytails and a boy was holding his father’s hand. When a man with a beaten wooden cart of lemons was heading out as I moved towards the fork in the street. I will forget that version. The version when he didn’t come. And the clouds clustered together were a reflection of the bodies beneath them. I will forget that version. I will memorize only the versions that came after that one.

*

A year later. Four o’clock. Another blaze in the distance. My eyes unable to shut. It’s unbearable to keep re-seeing the ruins of small bodies. A roar under a cry. A sea beyond a heart. Shadows beneath shadows. Boots pressing the air out of rooftops. The threat is everywhere, even in the stack of papers in front of me. I can’t sleep because the fear combined with the interminable vigor to resist it leaves me no time for caution; and time is outside of time here. We find unusual ways to survive each scar as night tries to escape the death it will awake to. The girl on the bus comes back to me–she reminds me to wait for the adhan, the call to prayer. The sun to rise. The church bells to ring. I’m in Bethlehem.

No one can reach grief on time to grieve properly. I’m sitting by the window where I’ve been sitting for hours. I lose track of how many. The stack of papers on the table in front of me is untouched.

Jesus was born here. But I haven’t seen Jesus for a while, something to do with not having a permit. It’s summer 2014. The third Israel-Gaza war in six years is going on. We want one minute to stop our hearts from racing. Just one minute. But here, one minute is a lifetime. No one can reach grief on time to grieve properly. I’m sitting by the window where I’ve been sitting for hours. I lose track of how many. The stack of papers on the table in front of me is untouched. I feel what I once felt standing in the middle of a grove in Jaffa, holding two oranges, one in each hand: a sensation that turned into a voice, a voice that mapped a past. From the corner of my eyes, I glimpse the cloud flirting with the sun, on and off of my face. I start writing about Lifta.

It’s one of my favorite places, and one of the most stunning pre-1948 Palestinian villages in the District of Jerusalem. Lifta’s inhabitants were either expelled, or they fled. Earlier in the summer, before the Israel-Gaza war began, I asked a few writers and theatre makers to meet me there so we could ruminate on a play about the pre-1948 Palestinian village. What remains of the village is under constant threat of being razed.

Not long before our meeting, one of the Palestinian writers, currently residing in London, was denied entry into the country. No reason given. Then the one living in Haifa but originally from the hilltop village of Iqrit, in northern Galilee, had clashes to deal with. For a few years now, Iqrit descendants have been trying to reclaim their ancestral village. They confront a colony of jarring obstacles. Iqrit’s inhabitants were forced to leave their homes in 1948 when the new Israeli army alleged the area was dangerous. They were never permitted to return. Today, descendants are still not allowed back, even those who are Israeli citizens.

Can writers create in such a ceaseless twister of interruptions, barricades and heartaches?

This left one other person in Jerusalem. On my way to Lifta, I got a call saying that there were clashes in East Jerusalem preventing her from joining me. This is common in Palestinian life. I’ve written about it before. There is no easy way to explain. The restrictions on freedom and movement are interminable: checkpoints, the Green Line, Areas A, B, and C, or whatever identity card or passport they hold. Gazans aren’t permitted into the West Bank or anywhere. West Bank residents can’t go to the 1948 territories unless given a special permit, and those are rare. Palestinians with Israeli citizenship can’t live in the West Bank, and Palestinians in the diaspora are refugees and can’t live in Israel, the West Bank, or Gaza due to Israeli laws. And Jerusalem blue-card holders are under constant threat of losing their residency. Wherever Palestinians are dispersed in Israel, the West Bank, Gaza, in refugee camps in the Arab world, or displaced worldwide, they are confined to the particularities of whatever boundaries — national or physical, psychological or emotional — they were dealt after 1948. Can writers create in such a ceaseless twister of interruptions, barricades and heartaches? For nearly seven decades, Palestinian writers’ oeuvres have contributed to Palestinian, Arabic, and other letters, and left notable and cherished poetry collections, novels, plays, and memoirs. But I can’t help imagining how much more they could have created.

*

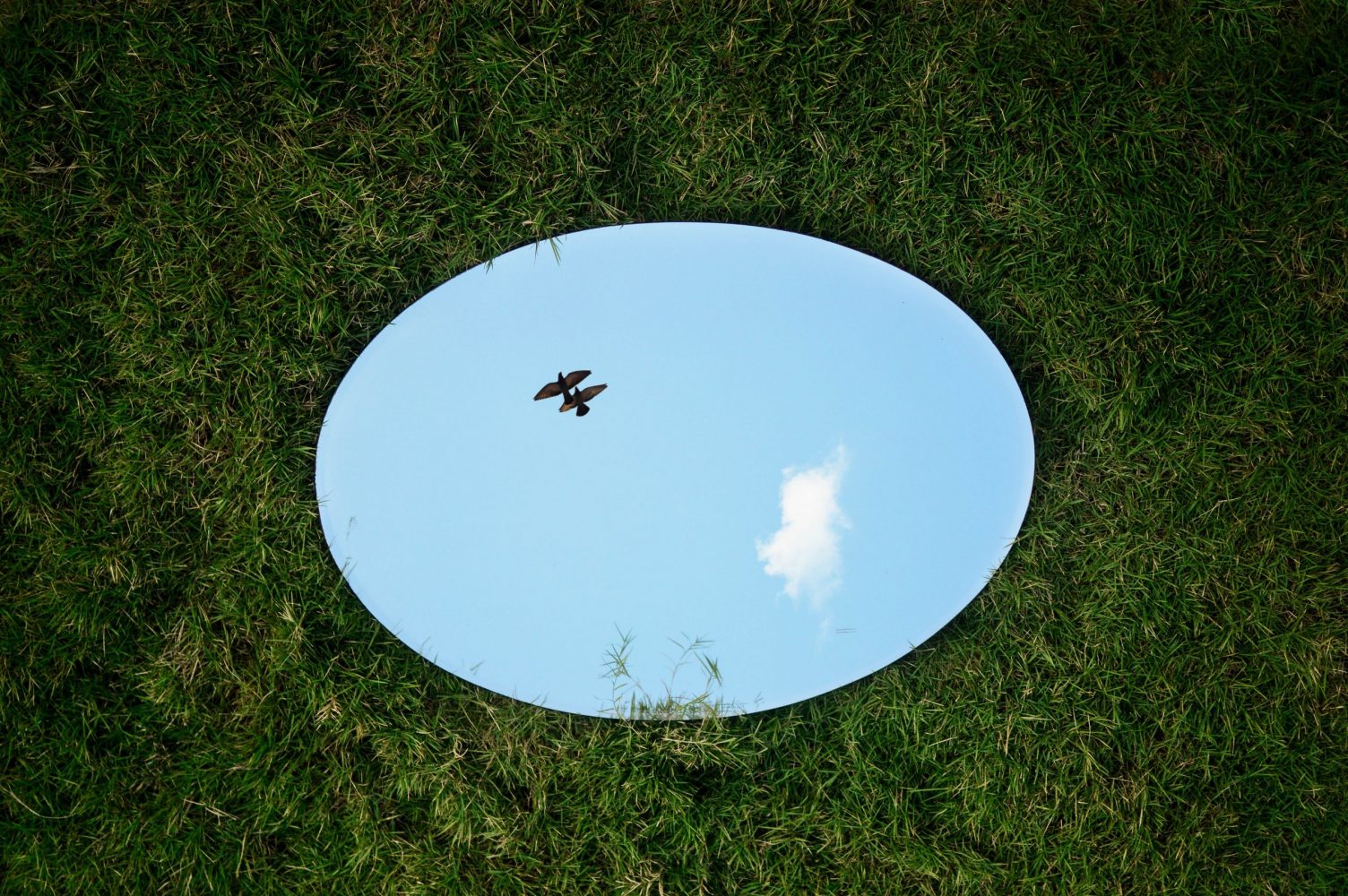

I don’t make it to Lifta until the following year, when I hike the steep slopes with my friend from Jerusalem. We allow the stones, like cascades of stars, to guide us. We stay silent. What could be said amidst such beauty, such horror, such grief, such love. The wild flowers speak to us. The jasmine and lavender speak to us. The empty old stone houses, gems of our heritage, identity and culture, speak to us. The olive trees speak to us. The mill speaks to us. The ancient spring speaks to us. The ghosts roaming the village speak to us. The bride and the groom from 1947, who haven’t aged a day, speak to us. And we listen. We mostly listen. What we hear: although there is nothing more to lose, no power has ever been able to steal memory.

The dry patches in between like sheets of hay, rough and songful. And the girl on the bus comes to guide me as I memorize Lifta.

Writers safeguard memories. We spot a Palestinian sunbird. It has orange tufts at the sides of the breast. My friend tells me as a child she would look for them, and that this one is a male sunbird, because its black feathers are lustrous blue in the sunlight. A blue so electric it mystifies us like a poem does when it mysteriously appears on the page. We sit under one of the arches of the old houses; we lean on the stones, cooling. The village is a perfect symphony of mystical green. The dry patches in between like sheets of hay, rough and songful. And the girl on the bus comes to guide me as I memorize Lifta.

My mind veers. I think of the expropriated Jerusalem houses not far away, in the neighborhoods of Talbiyah, Qatamon and Musrara, the ones that my sister so painfully researched and powerfully unfurled in her interactive web documentary art, “Dream Homes Property Consultants”.

Then I stop. Beauty is a scar. History is a room. Longing is a gale.

*

Was I really a young girl when I saw absence and recognized its broken lyric, now more riven? Was I really in my twenties in 1997 when Mahmoud Darwish asked me to interview Allen Ginsberg for his journal al-Karmel. The American beat poet spoke about being offended as a Jew at violent Zionists, and said, “The Israelis have fucked up with Netanyahu. They won’t have peace unless they have peace.” Is it 2015 and Netanyahu is still around? But would it make a difference if he weren’t? Would that stop Palestinians in the West Bank from being subjected to what the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) calls a “complex system of physical and administrative” control that includes “physical obstacles” (the Barrier, checkpoints, roadblocks, earth mounds, ditches) and “bureaucratic constraints” (permits, Area C, military zones), which “impede access to services and resources, disrupt family and social life, undermine livelihoods and compound the fragmentation of the [West Bank]”? Would the Mediterranean Sea be open to Palestinians, North to South, East to West? For now, the sea will continue to miss us.

Five o’clock. Summer 2015. A year has passed since the 50-day Israel-Gaza war and Israel’s annexation, only a few days after the Gaza ceasefire, of nearly 1,000 acres of West Bank land in a Jewish settlement bloc near Bethlehem, which the international press called “the biggest land grab in a generation.” The telephone rings, the voice says, “Look outside of your window.” I do. “Look down,” he adds. It could have been a Romeo and Juliet scene except the tired curves on his face tell me he can’t entertain even the illusion of our hearts. Who can, when seven miles is a long distance journey? The once sister cities, Bethlehem and Jerusalem, are now separated by a wall and love needs a permit issued by an occupying power.

This is where I understand myself best, amidst these limestones, these slender streets, in these hoshs, in these hundred stairs of the old city, under these arches, with Jerusalem before me and this person beside me.

We manage to smile and drive through the old city before it awakes. We pass through my mother’s quarter, Harat Al-Tarajmeh. I see my grandmother’s school, the former ateliers of the mother-of-pearl artisans, and the stone houses of close and extended families. This is where I understand myself best, amidst these limestones, these slender streets, in these hoshs, in these hundred stairs of the old city, under these arches, with Jerusalem before me and this person beside me.

We end up where we often do, having a conversation by the Nativity Church. Casa Nova, to be precise. Not long afterwards, we exit our hearts as we exit our bodies. We never reach our wounds nor get to our words on time. I memorize his hand instead of saying goodbye.

*

It’s now December. Every year, Christians worldwide celebrate Christmas. Some will come to Bethlehem. They will be told not to buy anything in the birthplace of Jesus because the natives are dangerous and untrustworthy — even best to leave their wallets altogether. While they pray, the natives will apply for permits to enter religious sites. Few visitors will discover what OCHA reports: that “more than ‘85% of Bethlehem governorate is designated as Area C, the vast majority of which is off limits for Palestinian development, including almost 38% declared as ‘firing zones,’ 34% designated as ‘nature reserves,’ and nearly 12% allocated for settlement development.” That Bethlehem along with Beit Jala and Beit Sahour are surrounded on three sides by the segregation wall. That “farmers in at least 22 communities across the governorate require visitor permits or prior coordination to access their privately owned land located behind the Barrier or in the vicinity of settlements.” That “over 100,000 Israeli settlers reside in 19 settlements and settlement outposts across the governorate, including in those parts de facto annexed by Israel to the Jerusalem municipality.” While they pray the systematic and discriminatory policy of revoking the residency of Palestinians in Jerusalem will continue. While they pray, writers will warn. Hearts will hurt. Rivers will be ruins. Words will be wounds. While they pray, love will ask the Song of Songs for love. While they pray, the daily, painful execution will continue. While they pray.

About the Author

Nathalie Handal’s recent collections include The Republics, lauded as “one of the most inventive books by one of today’s most diverse writers”; The Invisible Star; Poet in Andalucía; and Love and Strange Horses, which The New York Times says “trembles with belonging (and longing).” Handal is a Lannan Foundation Fellow, winner of the Gold Medal Independent Publisher Book Award, the Alejo Zuloaga Order in Literature, the Virginia Faulkner Award for Excellence in Writing, and an Honored Finalist for the Gift of Freedom Award, among other honors. She is a professor at Columbia University and writes the literary travel column The City and the Writer for Words without Borders.

All photos are courtesy of the author.

You can find all the essays from The Writing Life Around the World at Electric Literature.