interviews

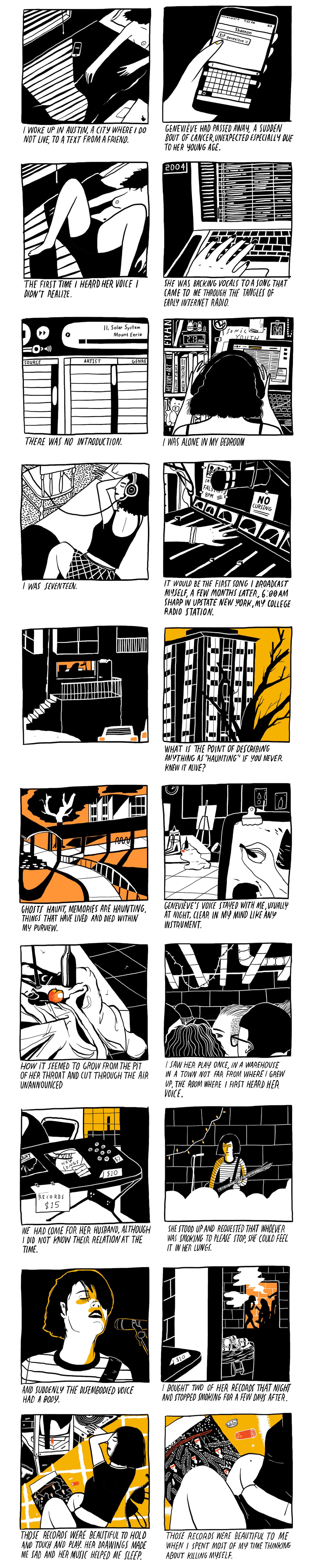

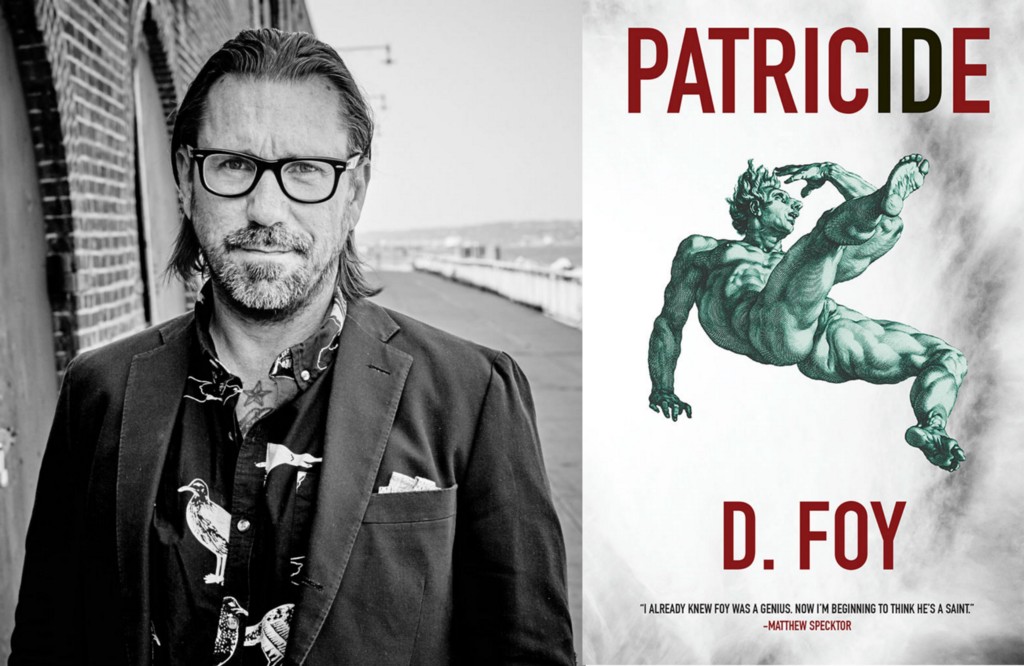

D. Foy’s Gutter Opera

Talking with the Patricide author about Monsters, Intuition & Guilt

There’s a bit of me that’s felt lucky to survive D. Foy’s first two books. Characters in his 2014 debut novel, Made to Break, find themselves trapped in a cabin in the woods. Rather than detach once the narrative moved into horror genre, I felt like I was in that cabin. I got closer and closer and eventually something flipped. And this is the peculiar quality to Foy’s prose: the reader stands among other characters and is almost surprised that his own thoughts come free of dialogue tags. It’s a rare experience. It’s like if I were Robin Williams walking around a gothic reboot of What Dreams May Come — paint from the world around me getting on my hands, in my hair, because everything is fresh and not yet dry.

Today, Foy releases his second novel, Patricide (Stalking Horse Press, 2016). Describing it in emotions — shame, open-heartedness, burnt-heartedness, rage, love — would make more sense than providing a plot synopsis of how a young man named Rice orbits his father. There’s real genius in how Foy renders the elevated stakes of young adulthood. Your pulse will quicken with each transgression, or even the thought of transgression. And just like his first novel, Patricide will become your world while you’re in its pages.

I had the chance to talk with Foy in preparation for his book launch at BookCourt.

— Will Chancellor

Will Chancellor: Let’s begin at the beginning. What was the genesis of Patricide?

D. Foy: When I first began the work — and this is usually the case for me — I was just whistling in the dark, as it were. Really this book began by accident — which is also often the case for me. I’d been going over a passage in another, related project in which I’d written insufficiently about the same father who ended up as the obsession in Patricide. It was just a paragraph, not nearly what it should be, I knew, once I began to chew on it. It needed fleshing out, not a lot, I felt, but much more than was there. But once I began the work, it wouldn’t stop. I wrote five pages, then ten pages, then twenty-five pages, and by the time I’d hit seventy-five, I realized, “Goddamn, I’ve got a whole other book on my hands.” This thing was huge, a real beast, I remember thinking, too huge and too beastly, I thought, for me to grapple with. I was pretty scared, in fact. I wasn’t writer enough to match the work, I didn’t feel capable to treat it sufficiently, it was altogether beyond me. In the end, the thing that saved me was remembering and then relying on an old maxim: “The work will show you how to do it.” Rather than punch my way through the book using cleverness and willpower, I let go — to an extent — and trusted that I’d be shown the way by the work itself as it progressed.

WC: We’ve talked about this before, but you’re no stranger to manual labor. And “The work will show you how to do it,” was my takeaway from the first few shit jobs I had. Was that where you first heard this expression?

DF: I don’t remember where I heard it, to be honest. I only know that where on the whole it’s true for most things, it’s especially true with art. You set out to explore something only to learn you’ve gotten in way too deep. You can’t move on any more than you can go back, or so it seems.

The artists who fail at their work do so, in my opinion, because they didn’t give themselves the benefit of the doubt, that they have within them everything they need to accomplish their ends. What I’m talking about here is faith. Doubt may come — doubt will come — but rather than look at it as hostile, I’ve learned to see it as my guide. Doubt pushes you forward. You don’t know what you’re doing. This isn’t working. You have questions whose answers demand you move a bit this way or that to find the crack you can pry into an opening. Still, nothing’s giving. This is where faith becomes critical. Without it, this essential belief in yourself and in your quest, you’ll surrender and collapse.

WC: Did that happen with Patricide?

DF: I was just this side of that at many points in the work, a hair’s breadth off from despair. Finally, I don’t know how, I saw that if I turned my back on this thing, it would go away forever. The universe would see my weakness and strip me of any vision, I’d never have another chance, I’d be crushed. But in that same moment I saw, as well, the opposite — that if I persisted, if I stayed true to myself and my conviction, the universe would give me what I needed to see me through. So I did. Sometimes a bit of light appeared. Others I stumbled through black for days. No matter what, though, I kept going. Way in the depths of the work, I became overwhelmed with the sense that this book could actually kill me, literally, that if I didn’t watch myself, it would take me out.

WC: Because it’s such a relentlessly ambitious monster of a book?

DF: Well, relatively speaking. That might not be true for another writer, but it was for me. The book and its making became much more than just a behemoth by virtue of its subject. The Father is an entity in itself, what after a time I began to think of in the same category of Moby-Dick — this seemingly omnipresent, omniscient, insurmountable entity that no matter what I did was going to smack me down again and again, you know, like Moby-Dick crushes ships with the snap of his tail. It was this realization that led me to the next, that I’d never overcome this thing if I kept at it as I was, like a puny naked stupid man throwing himself into breach. The work made it clear, as I was saying, that I had to move around the father and The Father both, that I had to come at them from every direction — hence the variety of viewpoints and modes in the book. One way wasn’t enough. I needed every way. Meantime, I held fast and persisted and never turned away. Every day of work at a point became one of those don’t-quit-five-minutes-before-the-miracle-happens moments. Just when I felt I couldn’t go any further, I told myself to hold out just a bit more. And sure enough, every time I did this, the way appeared, and I moved on to the next impasse. And then after a thousand pages, and countless revisions and hackings and maimings and surgeries of every sort, it was over, I’d finished the thing, a book about a monster that was never born and will never die.

WC: Seems like the Anxiety of Influence is really deep in there. You’re not really giving me something familiar, “Father is a tree whose shadow blah blah blah;” or something lyrical, “Father is a carpenter, planing and joining the world in a shed . . .” Instead, if I’m reading you correctly, you’re giving me a straight up, “Father is Moby-Dick — the whale, but also the novel.”

DF: Well, it’s not that The Father isn’t a trope for something much bigger. It is. Really, given our culture for the last several millennia, dictated and determined by The Father, which is to say a psychotically overweening patriarch, we could go so far as to say The Father is The World, about as big a trope as you can ask for, I guess. I was talking about this elsewhere recently. Patricide isn’t simply a story about some kid struggling to escape a wretched father and the legacy thereof. It’s also an allegory of a world suffering its destruction by the Powers That Be — The Father — the dynamo of whose rule is a greed so profound His vision — and ours, too — is limited to His own obsessions and their effects. There’s a father in Patricide, and there’s The Father.

This is the history of mankind. Taught by The Father, ruled by the Father, punished and rewarded by The Father according The Father’s whim, The Father of course having devolved into the status of a wicked buffoon, we’re most of us ourselves a legion of fools scrapping around at the bottom of the cave The Father led us into.

I mean, it’s no coincidence — a thing, by the way, I don’t believe in — that Donald Trump has assumed such a hideously imposing stature. He is very literally THE FATHER. He is at once the product and the symbol of our time. He’s The Father at his most gluttonous, scurrilous, pathological, diabolical, idiotic, cowardly extreme, the worst of humanity distilled into a single repulsive villain, now a juggernaut, really, a stinking one-eyed fiend. And what is happening in the face of this moronic, tiny-handed, tiny-dicked Cyclops? By and large, obsequy and pandering, on a scale we haven’t seen, thankfully, for a very long time.

It’s no coincidence, either, that we’re now calling our era the Anthropocene — very literally The Time of Man. Without the least hyperbole, we could as easily call this time the Patercene. We’re living on the edge of the apocalypse, seriously, with no one to blame for how we got here but our ridiculous selves. Someone on Facebook recently posted a quote from Chris Kraus — “I think desire isn’t lack,” she says, “it’s surplus energy — a claustrophobia inside your skin.” She’s right in the first. Desire isn’t lack. But neither is it energy. It’s delusion pure and simple, and this delusion, our delusion, is the catalyst for the expenditure of our energy toward all the worst ends. It’s always been so, in the quote unquote civilized world, and exponentially more so now. We want shit we don’t need because we’re told again and again we need a lot of shit. And who is it telling us this lie that we need all this shit? The Father, no doubt, in the guise of Capitalism in the guise of the megalopolistic Corporation. And what have we done in the name of our frenzied grasping after all this shit? We all know. No one doesn’t know. The answer’s all around us. We’ve poisoned ourselves and our environment — the place we live in, our home — to the extent that it’s nearly uninhabitable. I dug into a lot of this stuff in the 1,000 pages I just mentioned, but ended up striking it in the name of the work, hoping that what remained would be infused with its essence. I could go on and on about this stuff. Just ask my wife.

We’re living on the edge of the apocalypse, seriously, with no one to blame for how we got here but our ridiculous selves.

WC: I love how you’re talking about circling the father — even little hidden circles like in the word “dynamo.” There was a similar word that stayed in my head while I was reading: radial. I’m wondering if this came from the subject matter or if you find yourself thinking in circles about everything all the time.

DF: Yes, I am a circular thinker, as opposed to a linear thinker — but this is intentional. I’ve trained myself to use intuition as a strategy and technique. The line is not the way of things. The circle is the way of things, and intuition is the way of the circle, which is the way that’s natural to us but which over time — really, since the invention of the technology of writing by the Sumerians roughly five-and-a-half-thousand years ago, and especially since the invention of the printed word back in the mid-fifteenth century — we’ve shackled ourselves to a very unnatural way of viewing the world, which is according to the logic of the line. In the face of language, written language, that is, this stands to reason. One letter follows the next to make a word, one word the next to make a sentence, and so on. And this is quite literally how we all see the world now, through the line. But that wasn’t how we saw things before, and in my art at least I strive to remember that daily. There’s more to be said, but my point is that eventually it became clear to me how stifling the logic of the line is, and once I understood this, I determined to free myself of it as best I could, if only in my thinking and my art. In any case, when we work according to intuition, whose law is the circle, digression becomes very important, or rather, I should say, it becomes inevitable. And digression in its turn is the way to vision. By vision I mean, sight, as in to see clearly.

WC: Do you ever second-guess an image in your head? Or do you just take it as a given that the story is going there?

DF: I wrote Patricide via intuition and digression, the writing itself directed by the work — a mode, actually that I call “gutter opera.” The work showed me how to see, dimly at first of course but with increasingly clarity as I progressed. I couldn’t approach it head on, I realized, but only from a variety of approaches, what amounts to a circling heteroglossia of sorts. The father was at first inscrutable. So was The Father, though it wasn’t long before I saw that He wouldn’t ever not be inscrutable. With no way to go through these entities, I had to go all around them, using every means I had. That the word “radial” was in mind as you read isn’t surprising. Everything about the book is radial. The narrative employs all three points of view, in a whirling sort of collaboration, and a slew of narrative modes, each of them slipping and spinning one from the next. The book’s structure, too, is patently, intentionally radial. It’s the structure of a tornado. A tornado continuously turns on itself such that nothing can escape it even as it moves forward according to a trajectory that for all intents and purposes is unpredictable, leaving a wake of destruction behind it. The book’s structure and approach are at once a reflection of the devastation of The Father and an act of patricide. They use the patriarchal framework within which the novel has until now largely been created to destroy that framework. The Father’s way is The Father’s death.

WC: The great thing about a circle, or anything radial, is that whenever you slice it through the center, you’re left with two equal parts. I read the chapters that way: each intuitive path you take at the beginning is a plane, a plane that’s going to split this whole fucker in two, so long as you pass through the father, who as it happens is always at the center. You could start off talking about addiction. If you hit that center, you can trust the result to be symmetric. And then there’s the center itself. To me, the Father in your book is a crushing black hole, absolutely nothing. Was this something you reminded yourself of mid-digression? Is it a view you agree with at all?

DF: Yeah, I agree with it! And that’s the paradox of this figure, isn’t it? The Father is everything and nothing, and everywhere and nowhere. I don’t think I reminded myself of this so much as it reminded me, every day I sat down to it. How do you grapple with such a thing? Can it be grappled with at all? What do you do when the strategy or approach or what have you — what’s at least given you the sense, however false, that it’s working — abruptly fails, and you’re left flailing in a void? You have to somehow find your way back and start afresh, though doubtless from a wholly different angle. The circling seemed never to end in this struggle, until it ended, of course.

WC: One of the most painful truths to experience in reading this book is to see this abusive tyrant of a father as a yes-man in his public life. It becomes a fight against our own empathy to say fuck you to the father. And, to borrow your example of the tornado, the damaging wind is our own emotion whipping around and howling. It seems like the first response is to dull it, but who’s done that successfully for long? In some ways the mock heroics, or, if we read with different eyes, the arch heroics of Quixote comes to mind as a way of putting wind to windmill, if only to have something to fight. Which is more of a menace, a publicly powerful father or a publicly impotent father?

DF: Man, that’s like asking the difference between an ape in the jungle and an ape on a chain. They’re both menaces, but in very different ways.

The publicly powerful father is The Father books are full of. He’s the man Tacitus writes about in The Histories, for example, a tome, not incidentally, I read with ultra-keen interest while working on Patricide. The Histories is many things, but foremost among them it’s probably the greatest record of mankind at its worst, indexing with brutal dispassion not only every wicked thing a person can think of doing, but also the means by which men turn those thoughts to plans and then, with diabolical prowess, actuate them.

The story Tacitus tells is the story just about any historian will tell. What we aren’t likely to see in these histories, though, is the ironic flipside of the equation, how it’s the fathers that spawn The Fathers, and vice versa.

On the whole, it seems to me, the publicly powerful Father is a direct consequence of the publicly impotent father, the father, that is, who in his humiliation and shame projects a lifetime of anguish onto his son, physically and psychically, to the extent that the son, in his own pain, dreams of power enough to take his revenge and prove himself mighty, while waiting for and searching out the means to do it.

There’s a bit about this in the book, the stories of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao, and the labyrinth of cruelties they were forced to navigate as children. It’s enough to make any feeling person weep. To feel compassion for these men in the aftermath of their destruction is hard, I know, but I think it crucial to remember they were once children, too — albeit children on whom the world bestowed supremely raw deals. Brutal men are almost always brutalized boys. This is the saddest thing. Every terrible act The Father commits is in the end a gesture toward the love He never got. All He ever wants is to be loved. But mangled as He is, He can’t do more than devise mangled ways to seek out that love, and in the process mangle everything He touches.

Brutal men are almost always brutalized boys.

So really the publicly powerful Father and the publicly impotent father are scourges of the same degree, diametrically opposed, the one in the mirror and the one in the world. Together they amount to a Janus of sorts who, whichever way he turns, can’t do more than wreak destruction.

WC: The boy’s mother in Patricide is frequently described as being even worse than his father. “Already my mother and shame were tantamount, Lee Harvey Oswald and assassination are tantamount, the way AIDS and death are tantamount, the way 9/11 and terrorists and war mongering and greed are tantamount.” And yet the novel isn’t called Matricide. Why does shame force acceptance rather than action for the boy? And if the mother is shame, is the father guilt?

DF: I’m not sure I’d say it’s acceptance that shame drives the boy into as much as it is dread and then, later, powerlessness so crippling and sheer that the only thing he can look to for relief, at first, at any rate, is the lie that is his hapless father. It’s only in looking back at these times that Rice, as a man, can clearly see the double bind his parents trapped him in, and, as well, the consequences of that bind. He couldn’t accept, much less admit, what he knew his father to be, he says. His knowledge simply festered. And then he tells us that no sooner had “oblivion called out with her promise” than he obeyed. His father is a drug addict. Very naturally he becomes a drug addict, too. But not only does he learn the lessons of his father, he masters them to the extent that in the end he makes his father’s detestable qualities look like virtues. This is Rice’s action, the action of no-action, the action of withdrawal, the action of submersion, the action of consciously obliterating, to the extent he can, his awareness of his life’s terrible conditions.

And, yeah, while I’d agree that the mother is, among many other things, shame, and that the father is, to whatever degree, guilt, his father is so much more than only that. Were that all that his father is, I wouldn’t have written the book. Labeling the father as guilt incarnate is too reductive, I think. Rice’s father is a swirling complex of delusion, fear, power, abuse, kindness, denial, love, avoidance, and so on and so forth, never one or the other long enough for his boy to make any sense of. He’s so radically shifty that Rice can’t understand him or his motivations from any single vantage. His father is insubstantial to the extent that to grapple with him, Rice is forced constantly to move around him in the circles we’ve been talking about.

About the Interviewer

Will Chancellor is the author of A Brave Man Seven Storeys Tall, a novel about in between spaces, particularly those of father/son. He’s currently working on his second novel, To Test the Meaning of Certain Dreams.