interviews

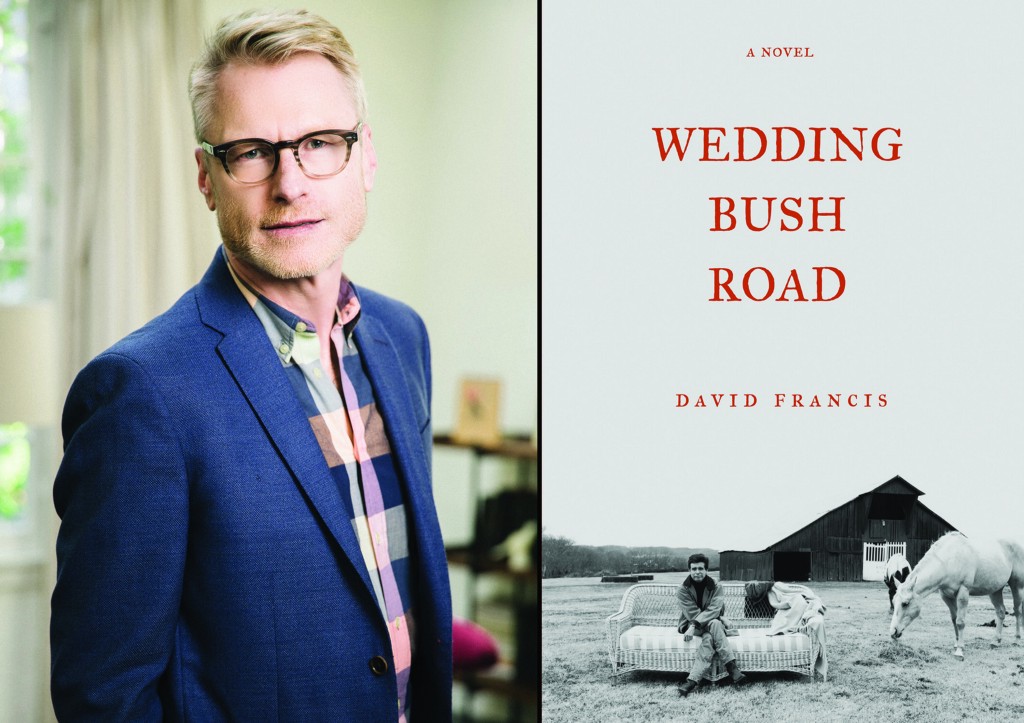

David Francis Goes Home

The Wedding Bush Road author on charismatic mothers and life on the ranch.

In David Francis’s third novel Wedding Bush Road (Counterpoint, 2016), Daniel Rawson leaves his new girlfriend, Isabel, behind in Los Angeles to spend Christmas week with his mother, Ruthie, on their family farm in southeast Australia. When he arrives, Daniel learns that Ruthie’s true motivation for luring him home is to manage the disputes between her ex-husband (and Daniel’s father), Earley, and his ex-lover, Sharen, a strangely sexy farm tenant with an affinity for arson. Sharen and her wild, young son, Reggie, complicate an already fragile family dynamic, especially as Daniel finds himself falling for her.

Francis is the author of The Great Inland Sea and Stray Dog Winter, which was named “Book of the Year” in The Advocate. He is also Vice President of the board of directors of PEN Center USA and works as a lawyer for the Norton Rose Fulbright law firm in Los Angeles. I met Francis soon after our mutual friend and writing mentor, Les Plesko, committed suicide in 2013. Francis invited me to sit at his table as “Les’s guest” at the Literary Awards Festival, and I’ve attended as a member of PEN Center USA each year since.

Over bowls of squash soup at Café Pinot, next to Central Library in Downtown LA, Francis spoke to me about his role at PEN Center USA, the merger between his publisher Counterpoint and Catapult, what it means to write with Les Plesko, and his latest novel Wedding Bush Road.

Andrea Arnold: This is the second book you’ve written about a relationship between a son and his mother. What is it about this bond that keeps you returning to it on the page?

David Francis: In real life I had a profound connection with my mother. I was what you might call a ‘mother-bonded child’ or ‘little husband.’ I had a very powerful, talented, interesting mother. And the mother in Wedding Bush Road, Ruthie, is pretty close to her. My mother and her sisters were on the first women’s polo team in Australia. And they played against the men! In the ‘50s! And they were better than the men. She was an amazing horseperson and a fierce personality, and so I grew up around that. I somehow keep circling that subject, even more while writing this book because she had a stroke and then she died while I was in the midst of writing it. That relationship was powerful enough that it was one of the reasons I moved eight thousand miles away.

My first novel, The Great Inland Sea, was set between the 1880s and 1950s. This new novel is more contemporary. The first was loosely based on the story of my grandmother growing up in outback Australia a long time ago merged with my own story of coming to the U.S. to ride showjumping horses, except set in the 1950’s. When I was at law school, my grandmother had gone blind. She was in her late nineties and I would sit with her and listen to her stories about her Austrian (yes Austrian) opera singer mother who was dragged by her Scottish husband to a cattle ranch of almost 100 square miles in the middle of Australia. There, my grandmother had a really unusual childhood, and I thought one day I would write those stories. Wedding Bush Road was more birthed by my relationship with my own mother and family, and the horse and cattle farm I grew up on (a mere 500 acres), rather than my grandmother’s experience deep in the outback.

AA: To me, the story of this family felt like an Australian August: Osage County. With a vast history. Can you say more about the origin of this fictional family?

DF: That’s an interesting analogy. Especially as Wedding Bush Road is in many ways, a kind of embellished memoir. The mother and the father are pretty close to reality. I have a brother and a sister who (lucky for them) don’t feature into the book. I always seem to write a narrator that is an only child, because it seems easier to deal with or maybe it’s a form of narcissism. The Sharen character is vaguely based on a tenant woman that we had on the farm, while the Reggie and Walker characters are the most manufactured. Recently, I have been realizing that they represent aspects of my own personality — the wild teenage boy and a darker side. I didn’t realize that until after I finished, but I’m talking about that in therapy now. [Laughs] My therapist read this book and she had all these questions! She would say things like, “There aren’t as many references to breasts in this book like in your last one.” She counted the number of references to nipples in Stray Dog Winter. She seemed pleased that there was a more nurturing relationship with breasts in Wedding Bush Road.

AA: Sharen is my favorite character. Probably because she was wrought with conflict. Just when the reader thinks she’s good for Daniel she has a meltdown. Was the real Sharen really that nuts?

DF: Yes. I went back to the farm one Christmas and my father had this woman ensconced in a cottage that had been my grandmother’s house that had been cut into parts and hauled on trucks to the farm. She was a bit crazy and feral. I had a terrible falling out with her because the situation was just so out of hand with her horses and son and my father. I started writing from that experience of anger at what my father had wrought. The book is a conflagration and a conglomeration of family stories and my own experiences and life on that farm which still exists. My sister lives there now, runs the pace, and I’m going back in a few weeks. We have about a hundred horses and a hundred head of cattle. When I was growing up there we had about a hundred and eighty horses. My father was a polo guy. My mother was a pretty famous riding teacher in Australia. We had our jumping horses, and all the rich people from the city would board their ponies and horses there. There’s a great big old homestead and up to thirty kids from the city would be staying with us in the holidays. I stayed in the meat safe and my sister in the bath of a giant unused bathroom where the cook had her bed. The cook who was my mother’s school friend and bridge partner — they were second in the Australia-wide bridge pairs!

AA: The portraits of deceased family members hang on the walls like in any good haunted house. In the writing it was a nice way of showing the generations that came before them. Why was it important to include Daniel’s dead family members in this story?

DF: Well, it’s set in a house that I see very clearly. Our family has been there for fifty years, since we moved from my mother’s family’s farm. The house has a formal dining room with an odd array of portraits from different generations. There’s Aunt Emma Charlotte hanging there and she’s really scary looking. She is my mother’s great aunt or something. In some ways it was easier to access this Australian setting at Tooradin than the Soviet Moscow in my last novel, Stray Dog Winter. I had been in Moscow for a month but it was more of a reach fictionally. Here I knew that dining room where the early scene unfolds, where Daniel arrives from L.A. and sees his mother and the dog hunting a possum around the picture rail. I’ve seen that. Those portraits are there. I wrote what I saw. There was once a possum that was running around that picture rail and it did pee on the paintings. There were pastels of me as a kid looking strangely innocent and wide-eyed, and the possum peed on it. Daniel says, “In the eyes that were never quite mine.” I always felt there was something symbolic in that.

AA: I loved the line: “I come from a line of men for whom fucking around is a form of mourning, a way to forget the dead.” What does it mean in the story?

DF: In the novel the father, Earley Rawson, has a brother who drowned when swimming across a river with a loaded pack on his back, training for the army. My father’s was at boarding school and I think his philandering and sexual “acting out” or ways of using sex and romance to obliterate feelings or lust was his way of coping with loss, disappointment, sadness, and feeling less than his brother who was now dead. Then my handsome father married this very powerful woman that he never matched up to, so he goes and gets his validation elsewhere. Daniel struggles with this in his father and himself in the novel.

AA: Great way of saying it. Daniel hates this aspect of his father but he also acts out. So is Daniel’s cheating generational and something he can’t help, or is he coming to terms with his father by being just like him?

DF: Daniel has moved to America and is in this relationship with this cool woman named Isabel, who is a little bit out of his realm. It’s going pretty well, but he is called back to Australia. You know when you go home and you’re around family you find yourself regressing to your old self? There’s that weird thing where you become who you were before you left. Daniel has struggled a little with infidelity before, but now that he has returned to the farm he feels himself drawn to this Sharen woman, as if he’s becoming his father after all, and that’s one of his struggles. He doesn’t want to be that person but he sees his behavior and his American life with Isabel unraveling. He has traveled 8,000 miles from home to re-invent himself and he has been seduced back by his mother and finds himself reverting. All he has tried to escape is right in his face. We all know that feeling. I think. It’s this precarious relationship with who I am and who I was and where is my true home versus the place I am from.

AA: This might be a stupid question. I’ve never been to Australia. When you were growing up on this farm did you have contact with Aboriginal culture, is it still an apparent aspect of Australian farm life, and how did that part of Australia’s past make its way into the novel?

DF: That’s a good and complicated question. Where I grew up there were not a lot of Aboriginal people around, although there had been. In the generation before me there was an Aboriginal family that lived and worked on the farm. As a kid growing up I had a sense of that Aboriginal presence on the land. There was a place called Foxes Hill where I used to camp out and I always imagined it had Aboriginal significance, it emanated from the land, the trees and gullies. I felt connected to that world somehow. As a boy, I read a book called the Red Chief about an Aboriginal warrior in the old days. In Australia it’s tricky writing about that Aboriginal presence because the misappropriation of indigenous stories is a complex and insidious issue. Reggie is a wild white boy who grew up around Aboriginal families and absorbed some of that culture. He was more into it than the Aboriginal kids because he hung around the elders. It’s not clear in the novel but maybe he has some Aboriginal lineage through his father, Walker. No one knows. I’m not sure. His father Walker is darker, and I realize now he was based on a guy who lived on the farm for awhile. A farrier and drover and racehorse trainer who lived in a camper van there. These things keep appearing now that I’m done. I learn about the themes of a novel during conversations like this. I try not to analyze while I’m writing. I just write.

AA: You chose to tackle several different points of views from Daniel’s to Sharen’s, Isabel’s and Reggie’s. These other characters are causes of Daniel’s inner turmoil. As you were writing, how did the narrative lend itself to each POV?

DF: This started off as a short story that was published in Harvard Review and Best Australian Stories. Then I heard Reggie’s voice. He’s the young wild guy who is Sharen’s son. I heard that voice quite distinctly and started writing in that weird patois. He has a very Australian country way of expressing himself. I started cupping more scenes together by hearing the different voices. In the initial drafts there were more of the other voices, all written in the first person present. In most writing courses they would encourage you not to do that in one voice, let alone numerous, but I liked the immediacy, flow and variety of those points of view in the present. It gave the narrative some urgency and propelled the story forward.

As much as we pretend that these characters we create are separate from ourselves, in reality they are not as distinct as we think.

What’s interesting to me is that I realize all the characters I write, while being based on real people, all carry aspects of my own personality. And to see that manifest in a work without knowing it fascinates me. To realize that Reggie’s voice lives in me. As much as we pretend that these characters we create are separate from ourselves, in reality they are not as distinct as we think. They live inside us. People write to work out what they believe. I think it was Joyce Carol Oates or Joan Didion who said, “I write to work out what I think about things.” I write to work out what I feel about things. Writing, for me, has been an exploration of aspects of myself and different periods of my life.

AA: Were you writing sequentially?

DF: Mostly, yes. But I had no idea where I was going. I write genuinely organically in a Les Plesko kind of way. I would write whatever scene I was seeing. But I did write more sequentially than I had in the past. This novel unfolded in that way.

AA: I know what it means to write in a “Les Plesko way,” but can you speak more to it?

DF: For me it means writing in a manner that is inherent and not contrived or engineered. If I have some great idea of writing from A to B, then I’m always trying to nudge the story toward B, but maybe F or H are likely far more original and interesting. Les talked about writing the scene that is the most resonant now, the one that has to be written, that is calling you. As the writing unfolds sentence by sentence, each informing the next, it reveals itself and takes me on a journey I hunger for. And if I don’t know where it’s going then neither does the reader. You know when you read books and have a sense of what’s going to happen? Well, I like not knowing. It creates an adventure and excitement for me as a writer. I’m very able to stay in the scene I’m working on and not be projecting or setting things up for something that my mind has decided is supposed to happen. I’m more interested in what my unconscious mind is ushering forth, which is why I write a lot long-hand in my half-sleep, trying to milk the dream state.

AA: The chapters are broken up in days of the week. Is that a lawyer’s need for an outline? Or what led to the structure of the novel?

DF: That was imposed afterwards. I added the days once I’d finished the novel for us to more readily keep track of time. The story is at times dreamy and I felt as though it would help to know how time is passing. The chapter breaks tell us where we are. I don’t outline at all, but perhaps I still unconsciously have a vaguely lawyerly, logical part of my psyche that I access more than I realize.

AA: When did you find time to write a third novel while practicing law?

DF: I have a very marginalized situation in a very big law firm. We have over 3,000 lawyers worldwide. I have arranged some flexibility. I get paid considerably less than I should but get billed out at a high-ish rate. It makes sense financially for the firm and I can get two or three months away. I received a writing fellowship in Paris at the Cite International des Arts and returned for a month each year for a number of years, and I go back to the farm and write. When I wake up I scribble longhand and I often write in my office in the evenings. I used to be very compulsive about the work, writing something every day, but I have to admit that more recently I write when I’m compelled to. I used to be very disciplined and now I only write when it’s there, as if I wait for the sentences to fly in to my head from somewhere, and then I run with them. I also find that because I fight for the time to write, when I do there’s usually something to be written. I’m basically crazier than I appear, so I work hard on myself with therapy and meditation and so on, so that I can be in a place where I can serve the story.

AA: What do you do for PEN Center USA? How did you get involved? Why is the organization important to you?

DF: Needless to say, I had always heard of PEN Center USA, mostly in the context of book awards and freedom-to-write advocacy, but had not become involved. A number of years ago, I was button-holed (in a lovely way) by Jamie Wolf at a dinner party. Jamie vigorously encouraged me to become a member. The next thing I knew, I was being seconded onto the board. Soon after, I was elected Vice President alongside Jamie. I go to a lot of the PEN events, including this year’s International Congress in Quebec City as representative of PEN Center USA where I learned a good deal about the “freedom to write” mandate, among writers representing more than sixty countries. Writers all around the world live and write and struggle in a very different reality from ours. In Quebec, the representative from Egypt abstained from voting on an LGBTQ initiative for fear of her safety as a writer. We have no idea what it takes to be a writer in Egypt, Iran, Ethiopia, Eritrea, our unholy ally Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, and sadly, still, Cuba. I’ve also been involved with the Emerging Voices and the Freedom to Write programs. Pen Center USA is a wonderful organization. I’m delighted to be a part of it.

AA: Did the merger between Counterpoint and Catapult affect you and this novel? What’s in store for this new publishing house?

DF: My first novel was bought in the UK by Fourth Estate, and as soon as I signed my contract they were bought by Harper Collins. Harper Collins, of course, is owned by Rupert Murdoch, who grew up on a farm not far from us in Australia! My grandmother and his mother were very good friends. And Murdoch is such an evil creature that I thought, how can I be writing for Murdoch! Then, I was with MacAdam/Cage here in the U.S. and my second novel came out right as they were going belly up! So my second novel was severely under-published; even though it won prizes and was well reviewed, it didn’t sell as it should have. Now, as Wedding Bush Road is coming out, Counterpoint is being bought by Catapult. At first I thought, yikes, but I now realize it’s a good thing! I think it’s a nice synergy. Catapult has a strong new media focus (doing with Electric Literature, Lit Hub, etc.) and is very forward-thinking while Counterpoint is arguably a more traditional environment, and probably the biggest and best of the independent houses. It’s a nice marriage. I think it’ll be great for all involved so I am delighted.

AA: Who were your early influences? Or your favorite authors? When did you know you were a writer?

DF: I always secretly wanted to write. I was doing horse stuff and practicing law, running around like a fart in a bath, running from L.A. to Palm Beach to compete at horse shows, and I was in therapy talking about what I really wanted from my life. I started doing morning pages, writing longhand stream of consciousness stuff in bed when I woke up each day. I had a writer friend, Josh Miller, who said if you want to be a writer you should go to Les Plesko’s class at UCLA, and if he likes you he’ll invite you to his private workshop. That’s what I did and became part of a new world of L.A. writers. I had never written anything and was workshopping with people like Janet Fitch, experienced writers. It was Janet, Sam Dunn, Rita Williams, Mary Rakow, Julianne Ortale — they were the leftovers from the legendary Kate Braverman writing workshop. Now I’m still in a writing group with Janet, Rita and Juliane.

For me it was like coming to religion without any baggage. I was easily able to embrace it. There was something about Les’s work that was spare, beautiful, poignant and unusual. It resonated in a way and I was inspired by it. I learned to edit myself through reading my stuff out loud. I learned to edit other people’s work because I heard it. I loved the whole organic process that was encouraged there. I don’t know if it’s a way to great commercial success, but I know it’s how I love to write and I know it’s what I like to read — and that’s all that matters to me really. To write what I must write, what no one else can, and to be continually intrigued and enthused by the process and the results.

For me it was like coming to religion without any baggage.

I tend to love novels, more than an author’s whole body of work. I was very influenced by Lolita — it’s poetic, wry, confronting, and brilliant. A Sport and a Pastime. Salter is a truly underappreciated writer. Both those novels spend many pages moving through the countryside, Nabokov in America and Salter in France. In their different ways, they are like going on tantalizing literary journey. I also was blown away by early Coetzee. Disgrace, In the Heart of the Country. Hyper-masculine in some ways, but amazing. These days I’m mad at Coetzee for some reason. Maybe I miss the music of Africa that so deeply infused his earlier work. I also loved early Jeanette Winterson. I have been influenced by so many books, I could go on for days.

AA: What are you working on next?

DF: I’m working on a novel that’s set here in LA. It’s contemporary and funny and is based on a story that was published in The Rattling Wall and Australian Love Stories. It’s gay. My second novel, Stray Dog Winter, was also pretty gay. Wedding Bush Road is not and I get a little flak from the gay literary community for being gay and not necessarily writing gay stories. But I also fall madly in love with women at times and that’s just how it goes. I really have little idea what my next novel is about, but when people ask I tell them what I know: a young Los Angelino named Patrick (who affects an accent and pretends he’s from a ranch in Australia when he’s actually from a desperate chicken farm outside Ventura) is ensconced in a relationship in the Hollywood Hills with an investment banker, Arthur Borenstein. When Arthur adopts a child named Marvel from Honduras, Patrick, the one used to garnering the attention, feels betrayed. In an ironic turn of events involving a cat named Moses, Patrick leaves Arthur on a quest to become something on his own, maybe an artist, maybe a man, perhaps something else entirely. If I have to make up a theme I say the novel explores the role and journey of the puer aeternus (the eternal youth) as a theme and an archetype. But in truth, for me, themes reveal themselves in the writing or, as I am experiencing now with Wedding Bush Road, in the aftermath of reviews and interviews and discussions of the finished novel.