Books & Culture

Dearly Beloved: Authors Pay Tribute to Prince

As the news of Prince’s death spread through the Electric Literature offices on Thursday, disbelief hung in the room as clearly as the “Purple Rain” that began emanating from someone’s speakers.

Prince was — is — a cultural icon, one of the few who is known by a singular name (and, sometimes, with just a symbol). He was prolific: in his 57 years, he gave us the gift of a staggering 50 albums, plus the majesty of his Paisley Park home, recording studio, and vault, which held an additional 385 unreleased finished recordings at last count. The wonder of Prince’s music: every single thing he created is undeniably funky and full of life and gave his listeners the permission to feel deeply.

Prince was everywhere, and he was refreshingly inclusive. Who among us has taken part in or witnessed a karaoke session that did not include the hugely popular “Kiss,” assuring us we didn’t need to be rich or cool or experienced to rule Prince’s world? Prince was funny, too, as evidenced by his work on Episode 201 of the Muppet Show, where he serenades the most unapologetically original girl in the class with a song called “Starfish and Coffee.”

While not all of us had the joy of seeing Prince perform live, let alone meet the man in person, what has become apparent in the last several days is how much the magic of Prince is due to his ability to affect so many of us so personally. Often, Prince’s music was what we needed not only for a good dance party with a crowd, but in our most solitary moments, too — Prince and his music are there for us when we are going through internal struggle as much as when we are dancing freely.

We asked several writers to reflect on their memories of Prince — a favorite song, album, or moment — and what the work and legacy of the Purple One meant to them.

Jesmyn Ward, author of Where the Line Bleeds, Salvage the Bones, and Men We Reaped

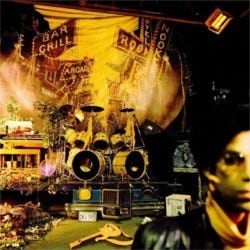

During the summer after I turned ten, multiple songs from the Sign o’ the Times album were in heavy rotation on black radio. That summer, a tumultuous one, was the last summer I would live in my grandmother’s house with my extended family in rural Mississippi.

In the room I shared with my younger brother and my two aunts and two cousins, there was a radio wedged on the windowsill, which my aunts let play all hours of the day and night. My mother and father had separated a year and a half earlier, and I was still reeling. I was also trying to process my immanent move to a different town, and enrolling in a new school as a junior high student in the wake of my parents’ split. Finally, I was in the beginning stages of puberty, which meant every day my flesh surprised me with some new alien, disturbing, horrible change. Boobs. Underarm hair.

As I sat in that room during the relentlessly hot, dogged days of summer, I listened to Prince sing, again and again, and the song that stuck with me, that I breathlessly waited for on the radio, was “If I Was Your Girlfriend.” Something about the beat, slow and somnolent, reminded me of the heat. When the melody dropped, it was like submerging myself into a warm body of water: for me, an amber river. The experience was simply visceral until his voice, high and sweet, crooned over the record, and suddenly, I was listening to Prince differently. I understood the longing in his voice. I understood his need to be the girlfriend of this woman he adored. To have her trust, to hold her confidence. To wash her hair, to make her breakfast. To hang out, to go to the movies, together. Underneath it all, Prince was saying this: he wanted to love her, and to be loved by her. For the first time, I understood some of the emotional power of Prince’s music. I understood the emotional subtext.

That summer I waited for my favorite Prince song to sound on the radio, I was just beginning to think about sexuality and gender, and “If I Was Your Girlfriend” confounded all of the theories I was constructing. It did so with lyrics and sound that were weirdly beautiful and frustrating, but still, I understood the soul of the song. I, with my heart still broken by my father’s leaving, understood what it was to love someone, to long for them.

Mira Jacob, author of The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing

I was living in New York for seven years before I ever went to that kind of a show. My New York was barely lit Williamsburg in the 90s, dancing in spaces so tight I’d lose the skin on my hips and shoulders. Madison Square Garden? I’d go blind there. Not my shows, not my people.

Except it was Prince. I mean, we’ve gotta do it for Prince, right? Alison said, so we did the math and decided it was totally worth it not to eat out for months. The night of the concert, we dressed in velvet and lace and got caught in a rainstorm along with everyone else, so we arrived looking like damp tissues.

I’m not going to write about how I couldn’t stop shaking the entire time, how watching made me want him so badly I spent $60 on what turned out to be an undershirt smeared with purple glitter glue, how I wore that thing to bed all summer long because it felt like the exact moment he filled the stadium so fully he was fucking me in the cheap seats.

But when he started singing “Purple Rain,” my heart sank. Who knows why? Maybe because I was just tired of sharing him by then.

He sang it close up on the mic, just him and the guitar, eyes closed so he didn’t see when the first umbrella popped open.

He sang it close up on the mic, just him and the guitar, eyes closed so he didn’t see when the first umbrella popped open. He didn’t see the next either, or the next, but he must have sensed something moving through the crowd because suddenly his eyes flew open and he gasped a little, right in the middle of the chorus. Gave us a smile, shut his eyes and kept singing. And then it was on. All of us scrambling and unfurling, his eyes flashing open again, up and down, shaking his head like I can’t believe you as the whole stadium launched high with a vaunted pop, pulling the ripcord that might keep us suspended above him forever. There he is, way down there, a purple flame in a pool of black. Laughing now, his smile working the words differently. He pats his heart twice, points to us, still singing.

Kathleen Alcott, author of The Dangers of Proximal Alphabets and Infinite Home

…I began to believe that my wishes then to die and fuck and lie and drink did not eliminate some life in which I might live and work and love and think.

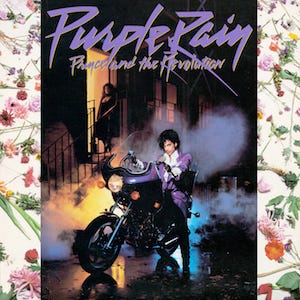

A cassette of Purple Rain — a copy made by someone else for someone else, scrawled in caps, which I bought at a sidewalk sale — came into my life exactly at the time when I needed to know a person could be many selves at once. In the space of my fifteenth summer, two people very close to me died, and when I began driving around my mother’s beaten Corolla shortly thereafter, Prince was the teacher I needed, the one who whispered, crooned, and screamed: identity lay on a continuum, was both familiar and inscrutable. Though I had changed overnight from a high-strung class president to a girl who smoked twenty-sevens and dated tattooed men with leases, that album lent me approval: I could masturbate with a magazine, I could hide somewhere between lover and friend, I could not know which leader I needed, I could exist that day only to get through that electric word life. I always listened to that album from start to finish, took cover in the way the songs fought with each other, and I began to believe that my wishes then to die and fuck and lie and drink did not eliminate some life in which I might live and work and love and think. I had little regard for the declining gas tank when Purple Rain was on, though I never had more than a few dollars, and I had always driven much too far from home.

Alexander Chee, author of Edinburgh and The Queen of the Night

For a glorious summer when I was 18, I had a DJ boyfriend who worked at a nightclub in Portland, ME, and all early Prince reminds me in particular of him and the pleasures of those summer nights, dancing late into the night, or driving around in search of a place to be, or getting ready for the night and you don’t know what will happen but you put on a song to get dressed for whatever you want to have happen.

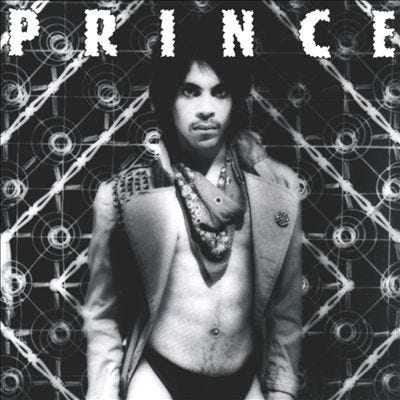

Dirty Mind — the album and the song in particular — is my personal favorite, a song and album I found around the time my voice was changing and all that remained to me of the almost three octave boy soprano voice I had once had was a falsetto, which seemed like the most embarrassing disgraceful vocal tool. Until I discovered… I could use it to sing along to Prince.

It is a song you have to strut to in order to dance to it, a short, desperate beautiful test.

The first notes are still one of those “divas to the dance floor please” moments. The song just feels like it is taking you somewhere, like a car you’re getting into with a party going on inside of it, and the narration, so simultaneously tense and sweet and seductive and ambivalent — the feeling that this person might just take it or leave it, despite the intensity of their obsession and desire. He circles slowly, calm to frenzied and back again. “In my Daddy’s car/It’s you I really want to drive” — sung so calmly, but the sentence is an explosion. And I love how the whole song sort of flips beautifully on this line: “If you’ve got the time/I’ll give you some money/to buy a dirty mind.” It is a song you have to strut to in order to dance to it, a short, desperate beautiful test. And when I hear the driving synth beat and keyboard, a little smile comes over my mind, and, well, I would walk away from pretty much anyone and anything I was drinking to dance to it. Though depending on who they were, I might take them along.

Amy Brill, author of The Movement of Stars

In 1984 I spent my bat mitzvah money on my first stereo and a few albums. Purple Rain was one of them (Synchronicity and L.A. Woman were the other two). I discovered Prince at the same time he toppled into the fantasies of millions of other people. But in my room, alone at thirteen, he was all mine. I had kissed a boy, but just; I knew what sex was in theory only. The beats and the melodies slithered into me one song at a time — by turns funky, sweaty, hyper, weepy, wild, and mournful. In the lean space of 44 minutes, every note tapped into something in me that was yet unrealized, a thrilling promise, a hint of the sensual, a whiff of the divine. In the years since, I’m sure that my most uninhibited moments have been spent in his company — sometimes with friends, sometimes by myself — but never alone. My conscious, my love. How he will be missed.

Casey Rocheteau, poet and author of Knocked Up On Yes and The Dozen

Let’s Go Crazy:

This song is an existential black anthem. It is gospel in the truest sense of the word. It won’t lie to you, it won’t quit.

By the time I was a pre-teen, visits to see my biological father became less frequent. He had gotten married when I was nine, to a woman who resented my existence at best. Often, visits were relegated to me babysitting his wife’s son, four years my junior, and stuffing into uncomfortably frilly dresses to go to church, despite my mother’s insistence that I be raised without religion. I disliked my stepmother, a hood girl gone bougie, because she constantly derided me for not being black enough, even as a child. I had a lot of difficulty with my father because she encouraged him to do the same. Most of my memories of them from childhood are rooted in alienation, save for one. My cousin and I were probably eleven or twelve, and we were cleaning the kitchen with the radio on. When we heard the other worldly gospel begin — “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life” — we turned the radio to top volume. We knew what to do. We sang into mop handles and twirled on linoleum. We pogo-ed on our awkward legs and smiled wide as we looked into each others eyes and yelled “Oh no, let’s go!” Halfway through the song, my father and his wife came to the doorway, looking very serious and still. We froze for a second, scared they were angry at us for playing when we were supposed to be doing chores, but it was a trick. They slid across the kitchen floor and belted “let’s go craaaazzzzyyy” and we laughed until our sides hurt, and kept dancing. Prince, for one swirling joyful moment, gave me a family who I knew loved and accepted me. I wasn’t zebra or lightskint heifer or even something to be ashamed of, because I had kin in Prince. Even when he said “in this life, you’re on your own” he was telling me I wasn’t. This song is an existential black anthem. It is gospel in the truest sense of the word. It won’t lie to you, it won’t quit. It is a celebration of mortality that swerves on everything that tries to break us. It is the home I always want to reside in.

Ryan Britt, essayist and author of Luke Skywalker Can’t Read

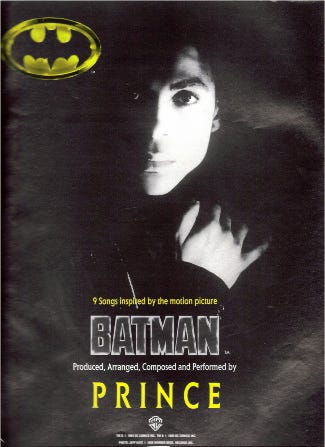

Having been born in 1981, I was only three years old when Prince and the Revolution released Purple Rain, so I’d be lying if I said I had a ton of childhood or pre-teen memories of the most famous of all Prince creations. But I do remember when the Purple One did the soundtrack for the 1989 Batman soundtrack. In the music video for “Batdance,” Prince cosplayed as the Joker while funking-up my young notions of what kind of music belonged in a comic book movie. Though the Danny Elfman score was probably more influential on future cinematic Batmen, the existence of not-so-famous Prince tracks like “The Future,” “Partyman,” and “Trust” introduced an eight-year-old me to a type of pop music that was challenging simply because it was something I wasn’t used to. When Jack Nicholson’s Joker is throwing money in the streets accompanied by giant balloons containing deadly toxins, Prince’s music turns this foreboding scene into a party. The fact that the cool funky music is associated mostly with the Joker and not Batman is deliciously subversive in ways I don’t think Tim Burton or anyone working on the film could have imagined. In short, Prince’s music in 1989’s Batman undercuts the cartoony violence of the film and replaces it — at least subliminally — with something more playful. Before his recent death, would anyone dream of putting original music from Prince in a contemporary superhero movie? Probably not. Guardians of the Galaxy famously employed a funky nostalgia-heavy soundtrack to rescue its generic plot from oblivion. While almost all of these tracks are fantastic, they do omit Prince, none are original, and they’re all also very safe. Prince on the soundtrack for Batman now? It would be like The Magnetic Fields doing the music for the next Avengers. Prince on that soundtrack in 1989 represented a willingness to take risks that I feel mainstream pop culture has sometimes forgotten was even possible.

For me, all great art creates confusion in your brain, or, at the very least, healthy contradiction. And in my first exposure to Prince via Batman, I was thoroughly confused as to how I was supposed to feel. Thankfully, because the rest of Prince’s oeuvre is just as unique — integrating very specific lyrical elements with unexpected melodies — I’m still confused as to why his music is as wonderful as it is. With Prince passing away so young, I can’t help but a feel a small part of popular culture has lost one of the riskiest and most vibrant artists of all time. And the craziest part is: unlike fictional characters like Batman or the Joker, you couldn’t invent Prince if you tried.

Mensah Demary, writer and columnist, Liner Notes

In the backroom of a bar in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, six months before his death, writers gathered together to worship, and unknowingly eulogize, Prince. Seven writers, one by one, stepped onto the stage and delivered the word to an audience of one hundred people, each writer revelling in the sex and satisfaction of Prince, in his divine lust, his ever-expanding Blackness, his unfathomable genius. As the night’s emcee, I stood to the side of the stage, waiting to introduce the next writer; in hindsight, with grief sieving the spirit from my body, I wish I too had delivered a word that October night. So I now offer as a coin tossed along with the billions thrown into the Pyre: Listen to Prince’s “Take Me With U,” from the eternal Purple Rain, while speeding down a highway in a Mustang. The rolling, hot pavement beneath the tires; the fresh white dotted lines slicing the road into thirds; the freedom achieved at ninety miles per hour, slashing traffic, passing tractor trailers, the Iowa terrain — with its flat, gold fields irrigated by colossal steel sprinklers — whipping past: combine all of this grace with the verse “Come on and touch the place in me/That’s calling out your name,” and feel the alchemy welling in your eyes, and witness the consecration of the electric word life Prince proclaimed to us as ours, forever. The music is the balm. Prince has left us for the Void, but it is still 1999 here on Earth. The music is the balm, and so we must continue to dance.

Marie Myung-Ok Lee, essayist and author of Somebody’s Daughter

Prince’s Purple Rain came out in 1983, when I was still a teenager — by then determined to leave Hibbing, Minnesota forever. I was at first dismissive of the seismic buzz emanating from this club, First Avenue, which I only knew of as a building near the grimy Greyhound bus station in Minneapolis; the Twin Cities was a place we visited a few times a year so my parents, Korean immigrants, could buy some kimchi at the lone Korean grocery in St. Paul.

Hibbing is actually Bob Dylan’s hometown, and townspeople didn’t speak particularly kindly of him — they actually didn’t say much at all. But this Prince person caused a bit of a scandal. “Is he wearing makeup?” “Is he…queer?” “Why doesn’t he have a last name? Even Bobby Dylan has a last name!” “Why does he…?”

Prince had come out of a Minnesota high school a few years before me, and I marveled at this person who was so happy with himself: a sexy weirdo. I’d heard stories of him getting pushed into lockers, spit on, called a fag. Yet, at nineteen, he made the Loring Park Sessions, a jam session, where he played all of the instruments, because — his face seemed to say — why not?

Prince basically showed that for the artist, the way is what you make. There was no one way to be a man, a person of color, to have and make a name. He wasn’t willing, as so many are, to cut corners on his soul so he could better fit in, a voluntary self-mutilation that I know I engage in, still, which stems from a fear of ridicule or people not liking me.

There was no one way to be a man, a person of color, to have and make a name.

In 2011, Prince let a reporter look in his fridge. Prince, being Prince, had: five pounds of Dunkaroos and a large jar of kimchi, “clearly actually buried in someone’s back yard at some point” of which he opined via email to the reporter, “This stuff is AMAZING.”

What can you say about someone who has both Dunkaroos and homemade kimchi in his fridge and in the last months of his life did a pop-up performance at the Chanhassen Dinner Theater?

Dearly Beloved

We are gathered here today

2 get through this thing called life

And, oh, what a life.

Laura van den Berg, author of What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us, The Isle of Youth, and Find Me

A handful of years ago, I was having a rough time. Nothing was “wrong-wrong” — i.e. no one had died — but a lot felt wrong. On a particularly shitty day I got the idea to host an afternoon dance party for myself, alone in my apartment, and it felt absurd and hilarious and a little sad and also pretty great. I listened to Prince’s “Kiss” again and again. How can you not feel better about life after hearing that song? These solo dance parties became a little secret habit I kept up for a while, and “Kiss” was always the first and last song I listened to. Of course, I had listened to his albums a million times before, danced to his songs at parities, blasted them in the car — but Prince once said “cool means being able to hang with yourself,” and “Kiss” will always be my very favorite Prince song because it helped me remember how to do just that. Like most Prince fans, I know so many people with stories of how Prince, who was never not himself, and his music helped them to feel less alone, to feel more at peace with their own struggling selves, to find whatever permission they needed. I hope desperately that Prince had some sense of, when he was no longer in this world, the ocean of gratitude and love he would be leaving behind. Thank you, Prince, for all that you gave us.

Morgan Jerkins, essayist and freelance writer

He talked about beauty and how it both deceives and bores him…

It is extremely difficult to try to pin down one particular Prince song that meant the most to me, because his catalogue is insane. Maybe I’ll just start with a recurring theme in Prince’s music, which is that beauty is both elusive and dangerous. In “The Beautiful Ones,” Prince places himself in a humble position because he wants to earn the affection of a beautiful woman. He ultimately realizes that the beautiful ones “hurt you every time,” presumably because they have so many suitors. And then in “Kiss,” Prince explicitly states that physical beauty is not a key criterion to arouse him, which meant a lot to me as a girl who used to be very insecure about her looks. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Prince is timeless to me. He didn’t follow certain formulas that demonstrated traditional masculinity. He talked about beauty and how it both deceives and bores him, which means to me that there is something inherently deeper that brings two people together. What that something is remains to be seen…or in this case, felt. But, for me personally, I believe his songs give us a glimpse of the eternal, something beyond ourselves, and romantic and sexual attraction is the magic through which to reveal that depth.

Maris Kreizman, author of Slaughterhouse 90210

Before I (or any of us, really) had the proper vocabulary to discuss the fluidity of gender, before I’d ever heard the word “non-binary,” there was Prince. “I’m not a woman, I’m not a man,” he sings in the first lines of “I Would Die 4 U,” “I am something that you’ll never understand.” As a kid I may not have been wise to all the details, but I did understand: Prince was beautiful. It was as simple as that. He was the first crush I’d encountered who didn’t look like the dudes in my teen magazines. He was so sexy because he was singularly himself.

Sean H. Doyle, author of This Must Be the Place

As a young guitar player and devotee to the Church of Hendrix, seeing the movie Purple Rain at 14 was like witnessing a resurrection, the spirit of Jimi flowing through this beautiful and tiny man and pulsing from the theater and into my own blood, already purple. I immediately went out and bought the soundtrack and fell madly in love with the sounds, with the personae, with the mythology of Prince. I followed him wherever he took me — and Prince took me to places I never knew existed — and I am all the better for it. If you walk into any kind of establishment during the next month and they are NOT playing Prince, leave and never go back there. Do yourselves and the world a favor tomorrow: wear some purple, some dark shades, and get your strut on.