interviews

Desert Poetry in the Digital Age

These Saudi poems inherit a borderless land bathed in the blue light of a networked world

In Tracing the Ether: Contemporary Poetry from Saudi Arabia, theorist and translator Dr. Moneera Al-Ghadeer gathers sixty-two poems by twenty-six poets who have inherited both the ruins of pre-Islamic longing and the blue light of a world digitally mapped and endlessly refreshed. Tracing the Ether is one of the first English-language anthologies to present Saudi poets not as cultural emissaries, but as participants in a shared global lyric—writing through the accelerations and dislocations of the digital age.

Al-Ghadeer’s scholarship has long traced how memory and language persist against erasure. Here, she extends that inquiry to a generation moving fluently between the aṭlāl, or the ruins, and the algorithm. For her, the desert—once a site of origin—now flickers as a conceptual afterimage: a home without borders, continually overwritten and reread.

These poems confront the collapse of modernity, the instability of belonging, and the uncanny intimacy of technologies that archive even as they efface. A house shrinks into a pixel. A WhatsApp notification behaves like a revenant. Frida Kahlo and Mahmoud Darwish drift into the same stanza as if they’ve always lived there.

I spoke with Al-Ghadeer about translation as a form of return, the desert’s digital afterlife, and the new genealogies these poets make possible—genealogies shaped not by inheritance, but by echoes, traces, and the fragile architectures of memory.

Jood AlThukair: The anthology opens with Goethe’s declaration that “the epoch of world literature is at hand.” What does it mean, today, for a Saudi poet to enter the world not as an emissary of “difference” but as a participant in the universal?

Moneera Al-Ghadeer: The poets in Tracing the Ether claim their place by engaging with global currents: they address technology, converse with pop culture, and reference philosophical and literary figures. Technology and media dissolved cultural borders, enabling the rapid movement of events, ideas, and practices. These poems display a layering where unique local inscriptions are interlaced with universal phenomena, a synthesis that sustains the local and the global simultaneously.

This interplay demonstrates how a grounding in local particularity is generative, not just in engaging, but in illuminating or even reshaping the prevailing understanding of the universal experience. By introducing these new Saudi poetic voices, Tracing the Ether seeks to disrupt Anglocentrist discussions and demonstrate that effective universal participation lies not in assimilation, but in introducing new, complex experiences into the global conversation.

JT: You frame tracing as both a cartographic act and an elegiac one—a gesture rooted in pre-Islamic poetry yet reconfigured through Google Maps. What kind of “home” are these poets tracing when the map itself has become a mirage?

MG: The “home” these poets are tracing is not a fixed physical structure but an existential and conceptual graph—a lineage that memory compels them to map, even as technology threatens to erase [it].

The act of “tracing,” or “ather” in Arabic, is an elegiac gesture rooted in the ancient Arabian poetic tradition. Pre-Islamic qaṣīdah is preoccupied with remnants and fragments: the traces of departed tribes, the faint marks of henna or tattoo, and the fleeting scenes with the beloved.

These traces become sites where memory reclaims itself. The Arabic words for trace (ather) and ether(atheer) share the same root “athara,” which connotes the suggestive concepts of leaving or following a trace, in both influence and narrative.

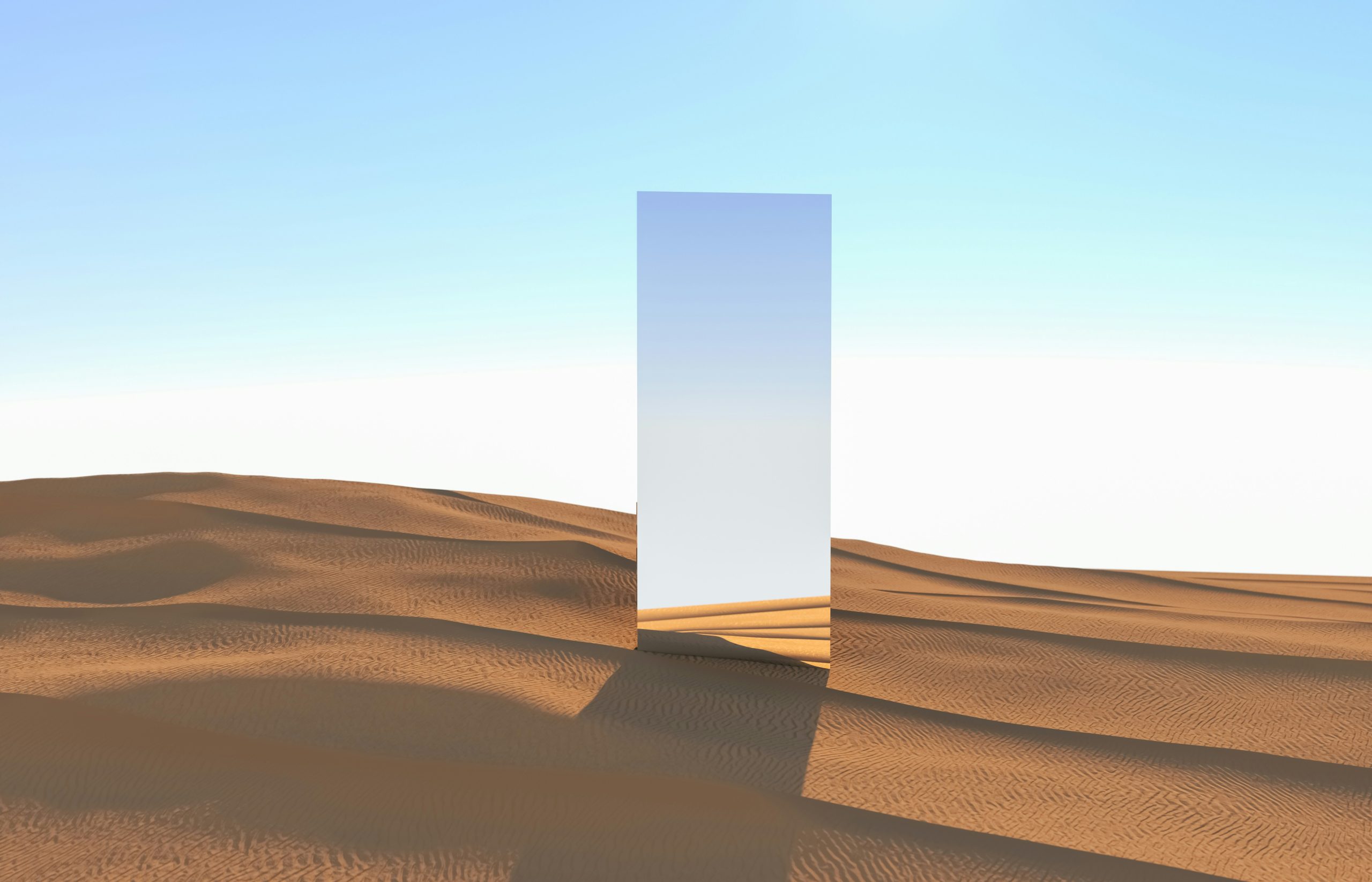

The desert is a philosophical condition for Arab poetics.

The contemporary poet’s need to trace these origins echoes a powerful comparative gesture: the irresistible, siren-like call of memory. The Sirens’ song in the Odyssey and the pre-Islamic poet’s halt at the desolate ruins (al-aṭlāl) both represent traditions that converge on the seductive, arresting power of the past. The contemporary Arab poet cannot abandon this enchantment.

The millennial poets—like Ahmed Al-Mulla, Ahmed Alali, and Mohamed Kheder—are concerned with the technological tropes that overwhelm belonging and dwelling. They track this lineage not as a literal return to the desert, but as an existential and conceptual graph that compels them to reposition home and situate their poetry as global while contributing to modern Arab poetics.

JT: Your introduction evokes a haunting line: “a home without walls or boundaries—the desert.” Do you see the desert as a spatial metaphor for world literature, or as its ethical counterpoint?

MG: This is my reading of the poetic depiction of digital displacement. It addresses the work of Ahmed Al-Mulla, whose speaker experiences his house’s features being digitally erased by Google Maps. He captures this loss vividly:

“In a nutshell: / after I left it / it left me. / It no longer has a door / or window / or bedroom. / It was simply a speck / on Google Maps”

The digitally featureless home becomes poetically reimagined as an unconditional open space. The poet elevates the lost dwelling of the vast, self-defining landscape of the desert, offering a sense of refuge, freedom, and radical becoming, transforming the “lost” house into a return to an open space. This poetic strategy directly confronts the way technology diminishes the experience of dwelling.

This digital disembodiment is repudiated in Ahmed Alali’s poem, “The Way to Our Home”:

“Google Maps lies / this is not our home / the house that my father built / its walls like cheeks that flush whenever we fall in love.”

Here, the digital map is a disavowal, unable to capture the emotional reality of home. This highlights the struggle of the millennial and previous generations to locate the authentic “home” in a hyper-modern, digitally mapped landscape.

The desert, therefore, is far more than a geographical setting; it is a philosophical condition for Arab poetics, a theoretical figure reinforcing the symbolic importance of the terrain. It represents a state of radical objectivity, a prelude of articulating the mute world.

While the desert signifies absence, it paradoxically stages the lyrical ego’s essential encounter with memory, forgetting, and loss—like the traces summoned in the pre-Islamic preludes.

In millennial Saudi poetry, the desert becomes a zone of radical difference, where poetry is pushed to its limits. The rhetoric of the desert in Arabic letters is radically different from Eurocentric views—including Deleuze, Guattari, Baudrillard, Foucault, and Derrida. While they conceive of the desert as metaphor, their readings diverge from the Arabic tradition.

In the Arab poetic tradition, the desert functions not only as the setting for an existential becoming and a contested origin that challenges the notion of “origin” itself. The modern Arab poet is “writing” in a pre-semiotic void, constructing the desert as an ethical counterpoint.

This act of inscribing meaning into the void establishes a responsibility to the non-existent, making the desert a condition for critiquing presence and absence. The poet’s traces transform the desert’s void into a site for creation and new language that resists traditional norms.

The desert is a testing ground where the poet’s efforts may be erased or remain incomprehensible until the reader responds to the “mark” left behind. It becomes, as some ecological readings suggest, a stage where a new system of meaning becomes possible. By focusing relentlessly on the physical characteristics of the object, the poet forces language to strip itself of its associative belongings and confront the “thingness” of things.

The algorithm teaches the poet that everything is becoming data—traceable yet fragile and erasable.

It is a kind of “counter-site” to the humanist tradition, exposing the arbitrary nature of linguistic structures. The poets’ relation to the desert is diverse, from Haidar Al Abdullah’s ironic summoning of Imru’ al-Qays, to Al-Mulla’s existentialism, to Khulaif Ghalib’s reiteration of Bedouin roots:

“I will live with the Bedouin starting today/with no household forcing me to stay/no palm tree forcing me to climb/no path bending its back beneath my feet.”

JT: You write that millennial Saudi poets have “moved away from the project of modernity,” no longer burdened by its dichotomies. What does poetry look like after modernity collapses, when even rebellion has lost its edge?

MG: To critically read millennial Arabic poetry, a critique of beginnings is essential. The prior Arab modernity project was fraught with debates, dichotomies, and encounters with Western thought. What attachment do these millennial poets have to pre-Islamic qasida?

Unlike modernist predecessors who sought to break with tradition, millennials are no longer bound by the imperative to conflict with the classical past. They approach tradition not as a burden but as a resource, accessed through ironic play and intertextual layering.

The poets infer a withdrawal from modernity’s grand project, allowing them to move beyond its rigid framework. Millennial poets theorize this collapse through silence and subtle renunciation of dominant rhetoric. The poetic emphasis moves away from ideological battles.

Their poetry becomes less concerned with proving modern approaches and more focused on direct expression of contemporary attitudes and responses to a world no longer defined by the narratives of the last century—including the Arab modernity project. This withdrawal allows the poetry to be evaluated on its own aesthetic merits.

JT: Technology in this anthology feels almost mystical—from WhatsApp ghosts to Google Earth elegies. What do you think the algorithm teaches poets about mortality?

MG: Technology in this anthology is a trope the poets incorporate, allowing the foreign names—Google Maps, WhatsApp, Clubhouse, Instagram—to blend with the Arabic verse while retaining their untranslatable status as remnants of the foreign object. Some poets stage a desire to engage with these platforms, while others depict the digital age with contemplative satire or melancholic observation. This shift signals a removal from ideological skirmishes of modernity toward a quieter poetic experiment.

The algorithm’s message about mortality is a cautionary tale for human creativity and presence. The output of generative AI—a synthesis of existing data—lacks subjective experience and originality. This replacement of human creation with derivative output becomes a parable of effacement: the startling erasure of the individual.

The algorithm teaches the poet that everything is becoming data—traceable yet fragile and erasable. It maps human life as specks or scars, acting as a hyper-modern aṭlāl: a precise mirror reflecting loss. Yet this mirror is limited, marked by the algorithm’s unreliability, duplication, and digital hallucinations.

JT: In poems where Frida Kahlo, Darwish, and Clubhouse appear side by side, the global becomes strangely domestic. Is this hybridity liberation, or another kind of exile?

MG: The juxtaposition of global and Arab figures—from Darwish to Frida Kahlo—is not a simple liberation but an assembly of transcultural encounters. This hybridity reframes poetic experience as intertextual participation. It confirms displacement as a shared condition, as when Haidar Al Abdullah places the millennial alongside the Arab modernist: “We bolted with the stallion, I and Darwish.” Or when Ibrahim Al-Hosain domesticates suffering through Kahlo: “Hitch our hearts to her anguish. / Our hearts drink, we drink.”

This is a form of digital and poetic citizenship asserting artistic kinship across boundaries, even if freedom remains unstable, as suggested by Hatem Alzahrani: “to be here with us now? / or not to be?”

JT: You describe translation as a “return to home.” In your experience, does translation redeem exile, or only re-stage it in another tongue?

Translation does not redeem exile; it transforms linguistic loss into a meaningful dwelling.

MG: Translation is a movement mediating the split between languages, engaging with exile. It cannot overcome displacement but attempts to create a passage—to carry and reassemble the text so it can reside in a new home closer to the “target” language.

Translation does not redeem exile; it transforms linguistic loss into a meaningful dwelling. Reading the Arabic alongside the English enables a mirroring between “home” and “displacement.”

JT: As a translator and theorist, how do you resist the institutional impulse to make Saudi poetry “representative”? To make it stand for something rather than simply be?

MG: Contemporary Saudi poetry resists being “representative” by its radical diversity. The notion that these selected poems can represent modern poetry in Saudi Arabia is destined to fail, because the diversity of this poetry is astonishing; it’s as if the poets are writing against the idea of a single movement. The greatest challenge was assembling an overview of the 62 poems given their variety. One cannot generalize their collective relationship to poetry, language, modernity, or tradition; these poems themselves display multiplicity.

JT: Fowziyah Abu Khalid (also featured in the book) once wrote, “I write because the wound refuses to heal.” What kind of wound, or silence, is Tracing the Ether responding to?

MG: The wound the poets inherit is linguistic and existential. Abu Khalid, pioneer of the prose poem and influence on millennials, stages a question: Where does writing originate?

In Desert Voices, I noted that the root of “kalimah” meaning “word,” metaphorically preserves the memory of injury. Imru’ al-Qays asserted that “the wound of the tongue is like the wound of the hand,” establishing language as a site to contemplate anguish.

The trauma also manifests through the suffering of the city. Abu Khalid’s poem “Beirut” captures this, asking: “Do they feel the festering ulcers of sleeplessness / On your beautiful eye sockets?” Beirut becomes a ravaged landscape, echoing the refusal of wounds to close.

JT: If you could imagine a new literary genealogy—not one of fathers and sons, but of interlocutors and echoes—who would inhabit that lineage beside you?

MG: Poetry constantly deletes and rewrites its relationship to predecessors. What we need is a deconstructive project critiquing the assumptions of genealogy, particularly the search for origins in Arab poetics.

This approach acknowledges influence without hierarchy, viewing the past as simultaneous voices rather than sequential chains of authoritative genealogies. The focus shifts from strict lineage to recognizing an enduring conversation across time and geography, where classical and contemporary poets speak to each other. This opens a space for comparative reading across global traditions.