Books & Culture

Discovering the Subconscious of Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Cajal’s The Dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal is a gateway into a fascinating mind

I am not a neurologist nor have I studied the intricacies of our nervous system in a way that would even come close to those who consider themselves neurology enthusiasts. Benjamin Ehrlich is one such enthusiast; having co-founded a blog entitled “The Beautiful Brain,” which focuses on dialogue between neuroscience, art and other fields of inquiry. Ehrlich’s most recent work is the first English translation of the dreams of Spanish born neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, who discovered that the nervous system is made up of the individual cells we know today as neurons. By virtue of his work, Cajal is often referred to as the “father of modern neuroscience.” When I ask Ehrlich if he himself studied neurology I find that his expertise began at the same level as my own.

“I started investigating the sources of my mind after college. I studied Comparative Literature. I knew nothing about science. Then I had, for lack of a better term, a nervous breakdown. One doctor sketched a neuron for me on a cocktail napkin. It looked like a stupid cartoon. I coopted the theory of reductive materialism to identify some concrete object for me to blame. Modern neuroscience seems to believe that that the mind emerges from the brain. My life was in shambles, and so it had to be my brain’s fault.”

Ehrlich began engaging in conversation with two good friends who were studying neurology, often arguing about the nature of things. One of them turned him on to Cajal. He was mesmerized with Cajal not only as a neuroscientist but also as a person. Ehrlich checked out books from universities on Cajal and asked friends to do so when he no longer had access, sent blind e-mail inquires to leading Cajal scholars, listened to lectures on iTunes University and Academic Earth, met with top neuroscientists to pick their brain, and made flashcards to test the retention of his self-taught science course.

“His life and work are great gifts that I am continuously exploring,” Ehrlich tells me when we chat about the book.

Ehrlich’s work is divided into two parts and indulges neurology experts as well as stirs a curiosity in those, such as myself, who have a vague understanding of this branch of science. The Dreams of Santiago Ramón y Cajal is both a portrait of Cajal’s legacy as well as a testament to the beauty and vulnerability that occurs when our brain and body communicates.

Though Cajal’s legacy is monumental; he is lesser known than his pioneering counterparts such as Newton, Darwin, and Einstein. For those who are unfamiliar with Cajal, the first part of the book reads as a biography. Readers become acquainted with his life and work, which are heavily intertwined. Before Cajal, the brain was seen as a “continuous web” as opposed to the individual units known as neurons that Cajal discovered them to be through his use of the Golgi stain. He, as well as Golgi, received the Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking work on the structure of the nervous system in 1906.

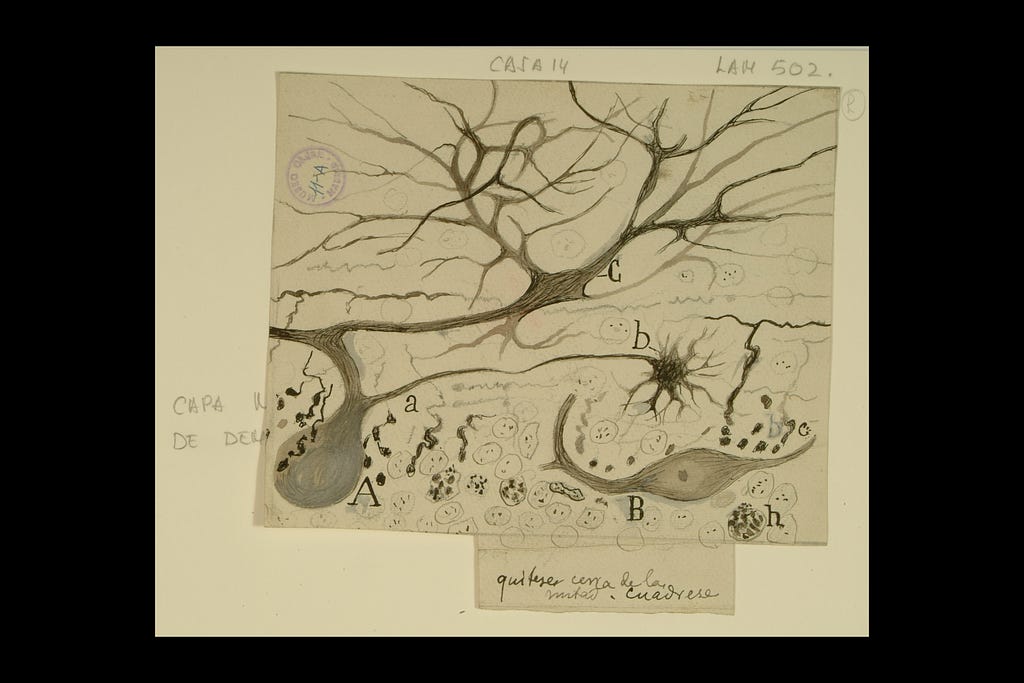

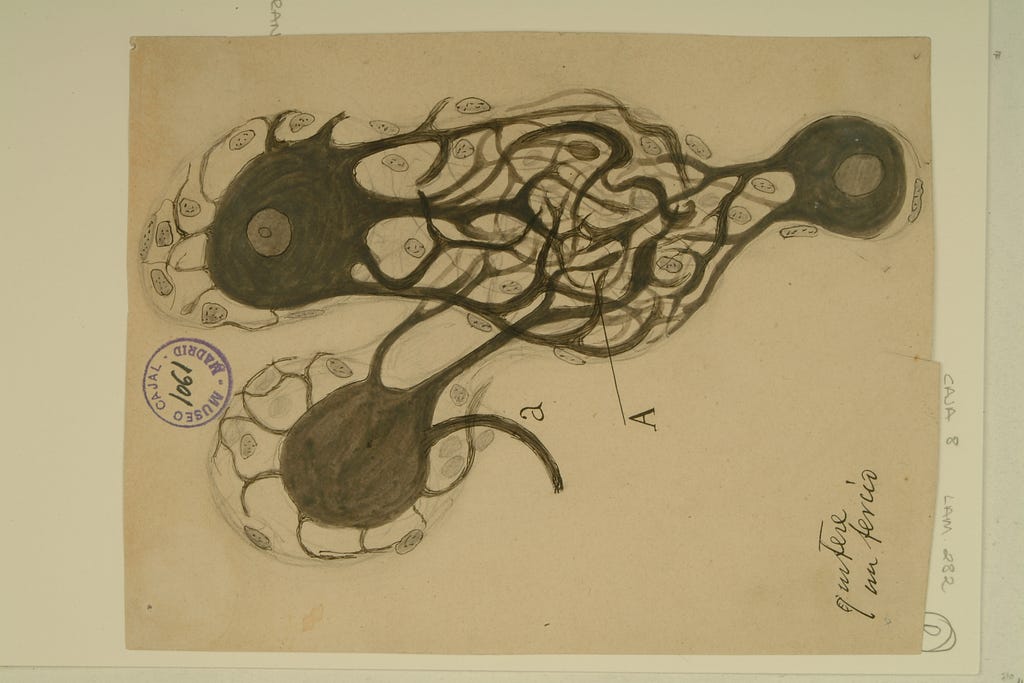

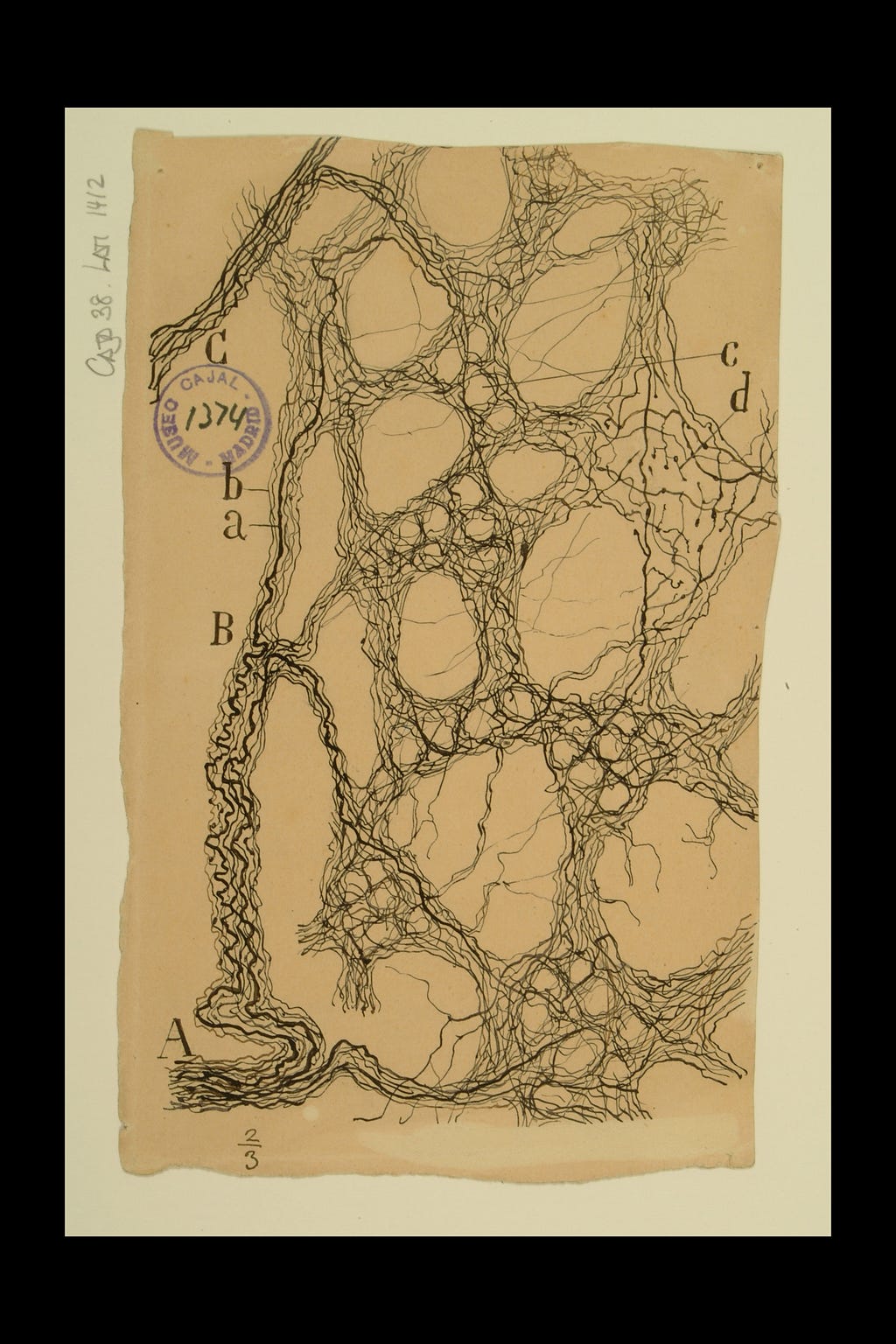

One of Cajal’s most interesting qualities was that he was a visual learner with an innate artistic ability. His initial desire was to become a professional artist. Cajal’s talent is evident in his sketches that Ehrlich has included in the book.

“The moment when I saw his drawings was like an awakening for me. They were intricate, fragile, and more astounding than I ever could have imagined. I thought about what Nabokov said about the “sob in the spine.” It was like my nervous system was speaking to me, like my neurons were finally recognizing themselves.”

In fact, his medical artistry from what he discovered beneath the microscope is still used today in many textbooks. His father, Justo Ramón, a local surgeon, was less enthused by Cajal’s artistic inclinations. He expected Cajal to follow the same medical career path as he had.

“Cajal’s father treated Cajal’s artistic impulses as symptoms of psychological disease, which he tried time and again to eradicate,” Ehrlich writes.

He attempted to persuade his son to study medicine via numerous methods throughout Cajal’s life. Ramón would confiscate any artwork of the young Cajal and destroy it. He had also banned works of fiction in their household, the only type of reading Cajal was allowed to indulge in were medical books. However, Cajal was still an avid reader of fiction despite his father’s efforts. His mother would pass novels to him in secret and he also sought books outside of his home.

Double Take: Joan of Arc in a World of Endless War

Perhaps one of the most drastic attempts by Ramón to persuade his son to study medicine occurred when Cajal was sixteen years old. His father brought him to a local cemetery where they exhumed a corpse and Ramón demonstrated dissection. This experience successfully ignited an interest in anatomy within Cajal and he began to connect his love of art with science. He eventually enrolled in medical school. In a sense, Justo Ramón’s expectations for his son had been fulfilled however, when Cajal left his hometown of Zaragoza, he never returned to see his father.

The heart of the biography draws parallels between Cajal and Freud who were contemporaries. Freud’s theories fueled Cajal’s desire to begin recording his dream diary. Cajal began taking notes on his dreams at sixty-six and continued to do so for the next sixteen years. He recorded his dreams in opposition to Freud; his objective was to counter the theories of psychoanalysis, which he believed to be “collective lies.”

“Freud and Cajal are perfect complements. I thought of their relationship in terms of geometry. They were almost exact contemporaries. But their career arcs seem almost inverse and reciprocal to each other. Freud started as a neurobiologist (few people know about that phase), and Cajal started as an experimental psychologist (fewer people know about that phase). Each represents the foundation of a modern discipline — psychoanalysis and neurobiology — still vying, a century later, to define the nature of the human mind. I think that the biographies of these two men provide a lot of insight into their theories. It is impossible to separate the ideas from the human beings, in my opinion. The takeaway from this diary, for me, is that the two of them clearly needed each other. Cajal, with all of his unresolved issues with his father, might have benefitted from the analyst’s couch, while Freud, with his wilder and more speculative theories that departed from empirical fact, might have been wise to heed Cajal’s call for more scientific rigor and discipline.”

The last chapters of Part One give insight into the emotional aspects that Cajal has omitted in his dream records. Ehrlich fills in the blanks for us, of Cajal’s deteriorating health, his acute depression and reminds us of the things and people that Cajal loved. Around the time when Cajal started recording his dreams, his health had badly declined and he was advised by his doctors to stay indoors. A man who often found joy in nature was confined to his home for much of his old age. He withdrew from society, even declining to attend a ceremony celebrating Cajal’s legacy organized by the King of Spain.

“He was deeply wounded, and his was suffering was intense. That came through loudly and clearly. To some, Cajal is almost mythic. He propagated that image himself, from time to time. Despite Cajal’s best efforts, his vulnerability in this diary is everywhere. He notes his pain only glancingly, to insist that it isn’t painful. His wife dies, his health deteriorates, and his childhood trauma haunts him. It was and is an emotional document, signified by total absence of emotion.”

When I begin Part Two, Cajal’s translated book of dreams, I am reading his words with the knowledge that Ehrlich has provided me about Cajal’s disposition — how he pushes away emotion in an effort to seek logic. Ehrlich also notes that this practice may have also been done in an effort to salvage and protect his scientific mind in the wake of his ailing health. However, his seemingly stoic sentences carry more depth and struggle than one would initially think. He addresses dreams or rather nightmares that involve personal tragedies with a certain amount of distance. One dream in particular involves him seeing his dead wife and despite the love that Ehrlich has outlined in the first part of the book, Cajal makes no mention of the pain of missing her. In other dream entries, he concludes them with his own judgments with final notes such as “pure nonsense.”

When I discuss which of Cajal’s dreams had the biggest impact on Ehrlich he mentions another that involves family and loss, in which Cajal attempts to save his drowning daughter.

“The drowning dream sheds light on his suffering and that loss. That dream, which actually recurs once more, was all that I needed to read. It gave me a deeper respect for grief and how it might show up.”

Cajal never published this work and upon his death, left all his belongings & research to the university or his family but his dream diary was given specifically to his former student, psychiatrist José Germain Cebrián.

“If he wanted to destroy the work, because he felt that it did not succeed, because it was a weak rebuttal of Freud in the end, he could have tossed it into the fire himself. It is that old Kafka question. Then, to give it to someone else before he died, rather than publish it while alive, seems like he’s denying himself the ego gratification that spurred him to take up arms against Freud in the first place. Did he want it to be printed, or not? Did he want to be healed? That is the question.”

Germain, who ironically became an advocate of Freud, typed up the dreams, which had been written on loose notes and in the margins of magazines, into a proper manuscript. He held onto it after he fled Spain during Franco’s rise to power. His manuscript was recovered in 2013 and published in Spain in 2014.

Though Cajal recorded these dreams with the intention to test them against Freud’s theories, it is challenging not to interpret them through a Freudian lens. It’s hard to separate the man that we learn Cajal to be in Part One of the book from his subconscious we encounter in Part Two. This falls in line with Ehrlich’s motivation to bring a deeper understanding of Cajal’s legacy to readers as well as whom he was, and what he endured, as a person.

“I hope readers can be moved by the intimacy and vulnerability of the dream diary itself. It is challenging, in a way, because on the surface Cajal offers only the facts and not much emotion. Yet just behind the image that he is desperately trying to present, is all of this negative space, an ocean of sadness and longing. All that I wanted to do with my introduction was to help readers access this level by decoding some of the references and providing the necessary background. More than anything else, though, I want people to love and appreciate Cajal and his humanity, what he accomplished — which was incredible — and how.”