Books & Culture

Diving Into the Faery Handbag: On Fabulism

by Melissa Goodrich

“I know no one is going to believe any of this. That’s okay. If I thought you would, then I couldn’t tell you. Promise me you won’t believe a word.” This is the middle of Kelly Link’s “The Faery Handbag,” and you feel it, don’t you? That you want to keep reading? That you’re promising, actually, to believe every last word.

Because — we love stories with magic. It’s a delight when Peter Pan’s shadow needs to be sewn to his foot, when a house from Kansas spirals into Oz, when a wardrobe bursts open like a color, to let in snow fawns and seasons and lions and swords.

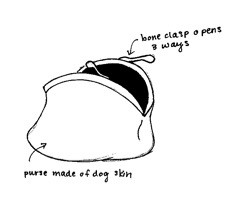

Or at least I love it. Fabulism is a curious way to explore and understand the ordinary. In Link’s story, the speaker spends her time hunting for this handbag. It’s black, made from dog-skin, with a clasp of bone that can open three different ways:

If you opened it one way, then it was just a purse big enough to hold […] a pair of reading glasses and a library book and pillbox. If you opened the clasp another way, then you found yourself in a little boat floating at the mouth of a river. […] If you opened the handbag the wrong way, though, you found yourself in a dark land that smelled like blood. That’s where the guardian of the purse (the dog whose skin had been sewn into a purse) lived.

Fabulism is a lot like this purse. It seems to belong to this world, but doesn’t follow all of the rules. It beckons you. It’s off. The more you explore it, the more mystery and power it has.

Fabulism v. Realism: “Just a Purse”

Now, realists do the great work of gesture, of symbols. Tim O’Brien places a pebble in the mouth of a solider who can’t kiss the woman who sent it in “The Things They Carried.” Junot Diaz shows deterioration in “Nilda” when she “put[s] on weight and [cuts] her hair down to nothing…” There’s a silver hair on the pillow in Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” an indentation from a head, “two mute shoes” on the floor. We know what these moments mean. Realists are trained in the fine art of subtlety, and it relies on the reader’s recognition of gravity and subtext and mood.

But Fabulism has much greater agency.

Think of how different Toni Morrison’s Beloved would be if Beloved were just the memory of a dead infant, and not a body — a real woman who comes out of the water, a woman who has aged in death, and haunts the house, has sex, and disrupts. Beloved is not a suggestion, but real in that world. And giving an abstraction a body raises the stakes. A body meddles. A body holds grudges. It is more powerful to actually be haunted by your dead baby than to be “troubled” or “perplexed” or to run a finger along the long undusted cradle. When Beloved gets hands and cheeks and bones, the trouble skyrockets. And isn’t that what loss is actually like?

Fabulism makes the emotional reality the actual reality. It’s more real to confront your demons when they are in the room with you. So, you can’t escape. Amber Sparks writes that “It’s a perfect time to turn ourselves inside out by turning the world around us outside in.” Meaning fabulism privileges how it feels –it’s real because it feels real.

Also it’s Fun — The World Inside the Purse

I think we like it — the magic. It reminds us of childhood stories — of Narnia and Oz and Tuck Everlasting, our sense that “yes, it could be possible,” and “yes, in this world, it is.” Maybe there’s this misunderstanding that because there’s magic in a story it’s inherently more infantile. But really, Fabulism gives us more language to use. It gives us the flexibility to play, yes, but play while expressing truths.

I think of Zach Doss’ work, which is hilarious and tragic and incredibly playful. He writes this enchanting series of boyfriend tales, and I had the joy of hearing him read some live at this year’s AWP. In “Jane Eyre,” the speaker discovers that if he cuts off parts of his boyfriend, those parts regrow. The lines are cutting (haha) and an uncomfortable kind of funny, when you hear “Just a regular boyfriend arm,” or “You suspend the cut-off limbs in scientific fluids,” or “Ultimately you wind up with so many spare boyfriend parts you could make an entire second boyfriend if you cut off a few more things, so you cut off a few more things.” There’s play here — it’s an experiment, a how-far-can-we-go tale, and there’s a delight in hearing what happens next: “Even a head. Your boyfriend even re-grew his head.”

The thing about magical realism is there’s no way to know the metaphorical implications of the story until it’s finished. At the end of Zach Doss’ story, the meanings are many and complicated. It could be about having a backup plan, about breaking someone into bits, about a love that becomes procedural, or hypothetical, about having a back-up plan fail, about loving a partner who is too busy loving themselves. You can’t set out to make these meanings when you write a magical story, but fabulism makes them plentiful, surprising, and varied. That’s part of the magic.

And then there’s the dark side: The Guardian of the Purse

The greatest part of the faery handbag is that there’s a wrong way to open it — meaning a dangerous way, a way that can eat you alive. And it’s that third compartment or “way of opening up” that separates the magical realism of childhood stories from the magical realism of stories for adults.

I think of Kevin Brockmeier’s “The Ceiling,” where the sky gets so low that by the end of it we’re on our backs, about to be crushed by it. I think of Aimee Bender’s de-evolving lover who is changing into smaller and smaller species, who is set all adrift on a pastry tin so she doesn’t have to see who he’s changed into beneath a microscope. The kind of pressure magic applies to a situation can be deadly. At the end of Ben Loory’s “The Well,” a boy is trapped at the bottom of a well because he used to be able to fly — and now he isn’t, and now he’s drowning. When we come to the end of the story, and his father is in the well, trying to swim his son to the water surface, and trying to pump his chest, but being unable to tread water and resuscitate, we get the sentences “But there is no way up. There is no way up. There is no way up. There is no way up.”

In these stories, the magic is more in charge than we are. It has a body that isn’t bound by rules.

In my fourth grade English class, the one I teach, we read Tuck Everlasting last. There’s a line I’ve been haunted by since I was ten, where Tuck, a man who cannot die, stares at the body of a man who was just killed, whose head was cracked with the thick end of a shotgun. And what I remember is how Tuck stares at this body: like a starving man staring through a window at a great feast.

This terrifies me. I think death is scary but I think not dying is scarier. And it’s scary because of the springwater in the wood that can make you live forever.

What’s interesting is my students don’t see it like that. The ten-year-olds I teach are enamored with the idea of everlasting — it sounds great to them — it sounds like invincibility potion. To me, it sounds like “stuck,” like “you will never be able to leave.”

I think this is why Kelly Link gave the faery handbag three compartments, and I think it’s why fabulism is so complex — it is all three at once — it is of this world, it does contain another world inside it, it can, if it wants to, attack. We want to dive into the Faery handbag — we want access to something magic and maybe dangerous. Because real human feelings are.