Books & Culture

Donald Trump in Literary Figures

English Professors Break It Down

In the realm of all things Trump, fact often cedes to fiction. Outlandish behavior dominates, and disregard for reality reigns. Comparisons to Andrew Jackson, Ronald Reagan, and Adolf Hitler are obvious at best and hyperbolic at worst. But maybe fiction provides the best guide to the essential truth of Donald Trump.

Literary parallels allow us to step back from political partisanship and avoid the associations — whether admiring or loathing — that trail historical figures. Asked who in fiction best represents the Republican presidential candidate, English professors offered up a slew of literary counterparts drawn from Shakespearean comedy to Gothic horror.

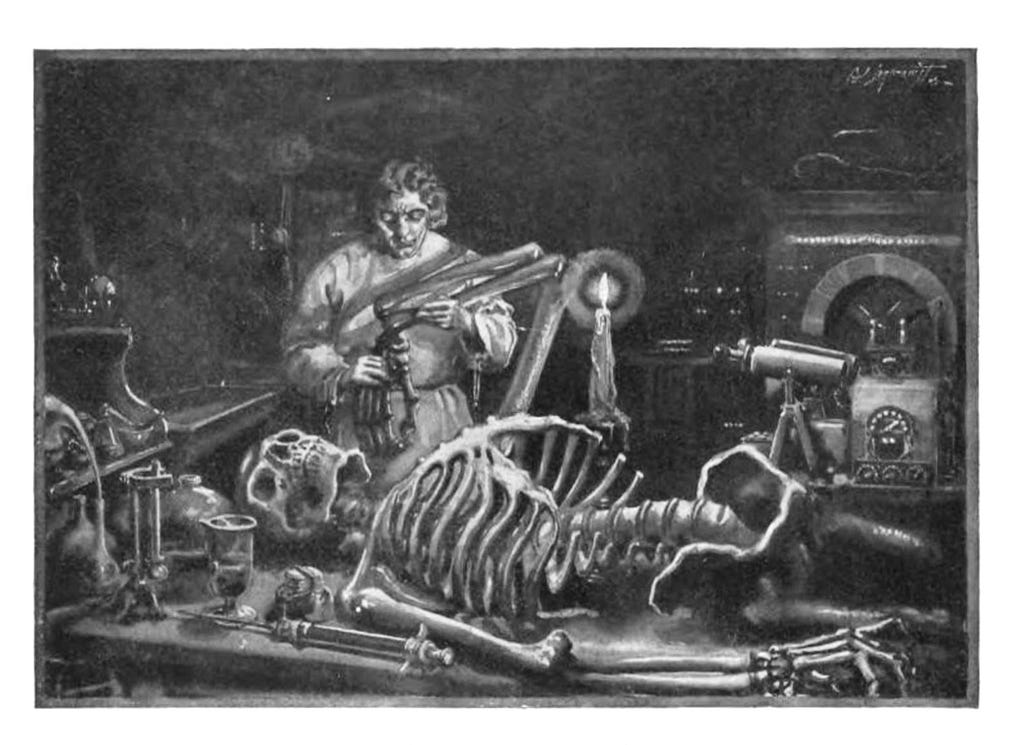

1. Unruly behavior: The monster from Frankenstein.

Talking to reporters, Nevada Democrat and Senate minority leader Harry Reid tied Trump’s rise directly to Republican rhetoric that created the “monster.”

“Trump is no anomaly. He is the monster the Republicans built. He is their Frankenstein monster,” Reid said. “Everything that he’s said, stood for, done in this bizarre campaign that he’s run has come, filtered up from what’s going on here in the Republican Senate.”

Political cartoons, too, play with monster imagery. One illustration from John Darkow in the Columbia Daily Tribune shows a monster-like Trump teetering forward, arms outstretched, grumbling, “Immigration bad! Mexicans criminals!” Next to him, an aproned GOP elephant holds jumper cables and muses to a Tea Party hunchback, “To be fair…we did kind of create him.”

“Trump is no anomaly. He is the monster the Republicans built. He is their Frankenstein monster,” Reid said.

The Republican party’s failure to disavow bigotry in its ranks is responsible for Trump’s rise, according to Robert Kagan, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “Trump is the GOP’s Frankenstein monster. Now he’s strong enough to destroy the party,” read the headline of Kagan’s recent op-ed piece in The Washington Post.

“It was Republican Party pundits and intellectuals, trying to harness populist passions and perhaps deal a blow to any legislation for which President Obama might possibly claim even partial credit,” he wrote. “What did Trump do but pick up where they left off.”

Susan Wolfson, a professor of English at Princeton University, said the monster comparison holds water.

“The basic gist is that the GOP has been a Frankenstein laboratory for decades, and the Creature to which they have finally given rampant life is Trump, who promises to wreak havoc not only his creator but on the world in general,” wrote Wolfson in an email. “It is a barometer of the post-novel, durable cultural life of the basic fable…of a creation that not only has gotten out of the control of its creator but also reflects something deeply monstrous about the political laboratory.”

The nuance which Mary Shelley brings to her representation of the Creature is lost on Trump.

Yet, in Shelley’s classic, the monster is intelligent and sensitive, tormented by his loneliness and the rejection of others. “Once I falsely hoped to meet with beings who, pardoning my outward form, would love me for the excellent qualities which I was capable of unfolding,” the Creature laments. “I was nourished with high thoughts of honour and devotion. But now crime has degraded me beneath the meanest animal.”

The nuance which Mary Shelley brings to her representation of the Creature is lost on Trump, Wolfson said. Instead of apology or remorse, Trump deflects wrongdoing: “It was locker room talk,” he said after being criticized for his boasting comments about touching women. In other instances, the GOP candidate simply denies having made statements that the record — often times video — shows him to have made. (Familiar refrains include “Wrong,” and “I never said that.”)

The novel offers one possible ending to the story of Trump and his creator, the GOP: “I have devoted my creator, the select specimen of all that is worthy of love and admiration among men, to misery; I have pursued him even to that irremediable ruin,” the Creature says.

2. Fame and finances: Mr. Merdle from Little Dorrit

In his self-serving pursuit of wealth and celebrity, Trump finds a kindred spirit in Mr. Merdle from Charles Dickens’s Little Dorrit. Merdle, whose name recalls the French “merde” (feces) soars to fame despite an apparent lack of talent.

Merdle’s facade of wealth, however, turns out to be a fraud. (Dickens based Merdle on John Sadleir, the Irish railroad speculator who later became a member of the House of Commons, who embezzled money and bankrupted the Tipperary Joint Stock Bank before killing himself. Before his demise, he enjoyed fame for his perceived financial success.)

“The famous name of Merdle became, every day, more famous in the land. Nobody knew that the Merdle of such high renown had ever done any good to any one, alive or dead, or to any earthly thing. All people knew (or thought they knew) that he had made himself immensely rich; and, for that reason alone, prostrated themselves before him,” the narrator tells us.

Merdle’s name — while not emblazoned on his towers in fat, gold letters — precedes him. The media seems to adore the man: “Mr. Merdle’s right hand was filled with the evening paper, and the evening paper was full of Mr. Merdle.”

Merdle’s name — while not emblazoned on his towers in fat, gold letters — precedes him.

Merdle’s wife is but an extension of his possessions, appreciated for her display value. “It was a capital bosom to hang jewels upon. Mr Merdle wanted something to hang jewels on, and he bought it for that purpose,” the narrator says. “Like all his other speculations it was sound and successful.”

But Merdle, like Trump, is no stranger to financial woes. Despite what the narrator calls his “wonderful enterprise, his wonderful wealth, his wonderful Bank,” Merdle falls deep into debt with his creditors. Trump, a rich man “suspiciously familiar with bankruptcy court,” as the Atlantic’s Andrew McGill put it, might sympathize.

“The critique of his lack of moral (never mind financial) worth reminds me of the contrasts made with Hillary: that’s he’s never done anything for anyone besides himself,” wrote Garrett Stewart, an English Professor at Iowa State University, in an email.

3. Sheer confidence: Bottom from A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Throughout the presidential race, Trump has exuded a seemingly endless reserve of bluster and confidence.

“I think my strongest asset — maybe by far — is my temperament. I have a winning temperament. I know how to win,” Trump has said.

That “winning temperament” could have been pulled straight from the character of Nick Bottom in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, said Peter Holland, a professor in Shakespeare studies at the University of Notre Dame. In describing Trump, other obvious parallels like Richard III, spring to mind, Holland said. But in many ways, Bottom best demonstrates Trump’s unfaltering belief that he alone can fix America.

When the craftsmen receive their roles for the performance of Pyramus and Thisbe, Bottom, a boastful aspiring actor, insists he can play any of the characters: the gallant lover, Pyramus; Thisbe, the object of his affection; even the tyrant, Ercles.

“If I do it, let the audience look to their eyes; I will move storms, I will condole in some measure. To the rest: yet my chief humour is for a tyrant: I could play Ercles rarely,” Bottom says.

Even when he is transfigured by the prankster, Puck, who turns Bottom’s head into that of a donkey, Bottom fails to notice. Instead, he shifts blame to those who point it out: “I see their knavery: this is to make an ass of me; to fright me, if they could. But I will not stir from this place, do what they can,” he says.

A comedic character, Bottom touches on themes of trust and gullibility, performance and reality. He wonders out loud whether the ladies in the audience will be frightened by his portrayal of Pyramus’s death, or misinterpret the roars of an actor in a lion suit for those of a real lion.

A comedic character, Bottom touches on themes of trust and gullibility, performance and reality.

However, Holland said, Shakespeare’s characters are thoroughly un-Trumpian in another regard: even in the depths of madness, they maintain some semblance of eloquence. Even King Lear, in his more incoherent moments, or Othello, when he falls into an epileptic fit, do not rival Donald Trump in his use of run-on sentences:

“When you look at what’s going on with the four prisoners — now it used to be three, now it’s four — but when it was three and even now, I would have said it’s all in the messenger; fellas, and it is fellas because, you know, they don’t, they haven’t figured that the women are smarter right now than the men, so, you know, it’s gonna take them about another 150 years,” Trump said at a speech this July in Sun City, South Carolina.

As Holland put it, “There is not even in Shakespeare anybody of quite the extravagant madness of Trump.”

4. Womanizing, racism, and xenophobia: Tom Buchanan from The Great Gatsby

The image of Donald Trump is hard to separate from his relationship to his possessions and other people. In a May 1997 profile of the real estate tycoon in The New Yorker, Mark Singer described Trump’s appearance, down to the complying strands of hair.

“He wore a navy-blue suit, white shirt, black-onyx-and-gold links, and a crimson print necktie. Every strand of his interesting hair — its gravity-defying ducktails and dry pompadour, its telltale absence of gray — was where he wanted it to be,” wrote Singer.

Compare that with the description of Tom Buchanan as he enters the “Great Gatsby.” Buchanan, standing before his Long Island mansion, exhibits his ownership of the things and people around him.

“He was a sturdy straw haired man,” the book tells us, “with rather a hard mouth and a supercilious manner. Two shining arrogant eyes had established dominance over his face, and he gave the appearance of always leaning aggressively forward…it was a body capable of enormous leverage — a cruel body.”

Tom Buchanan shares not only Trump’s hair color, but also his stance on the state of humanity. “Civilization is going to pieces,” Buchanan says before declaring himself a “terrible pessimist.” He has been reading a book called The Rise of the Coloured Empires. He tells the narrator, “The idea is, if we don’t look out the white race will be — will be utterly submerged,” laments that recall Trump’s thinly veiled euphemisms of “inner cities” and his descriptions of issues facing Black communities.

Tom Buchanan shares not only Trump’s hair color, but also his stance on the state of humanity.

“Buchanan is the villain of the Great American Novel,” said Daniel Torday, professor of creative writing at Bryn Mawr College. “He is a human instead of a monster.”

In the end, these human qualities are precisely what make both Buchanan and Trump scarier than Frankenstein’s creation, he said.

“What he ultimately does over the course of that novel is manipulate people in the goal of his self-interest. Myrtle’s death and Gatsby’s death — both events are the result of Tom’s having run rampant over people’s lives,” said Torday. “It’s hard to imagine a character that overlaps more clearly with this year’s GOP candidate.”