Books & Culture

Dungeons & Dragons & Communal Storytelling

The Adventure Zone podcast, metafiction, and assembling story

Early on in the fantasy role-playing game podcast The Adventure Zone, two of the main characters narrowly avoid strangulation-by-sentient-vine as they escape through the open hatch of a falling elevator. The three heroes of The Adventure Zone are Taako, a high elf; Magnus, a human fighter; and Merle, a dwarf cleric. In this scene, they ascend a fantasy skyscraper in order to confront a powerful foe, the Raven, who wields a relic that can manipulate natural elements. A writhing mass of vines controlled by the Raven approaches them from the elevator shaft below. Taako hangs suspended, clutching the feet of Magnus, who clings to a rope magically conjured in midair. Merle stands on the elevator platform nearby, deciding his next move. There’s a brief pause following this feat where one of the players breaks the fourth wall to comment on the story.

Clint (Merle): May I just say — good, vivid storytelling. Good storytelling.

Griffin: Yes, thank you.

Justin (Taako), in character voice: And nothing makes a story better than someone saying in the middle of it that it’s good.

Travis (Magnus): “This is good so far!”

Griffin: “Call me Ishmael, this book is gonna kick ass.” [crosstalk, laughter] “As God is my witness, this has been a fucking dope ass movie!”

It’s the kind of podcast tangent that normally ends up on the cutting room floor. But this self-conscious waffling makes it into the episode. This is a frequent move on the part of the McElroy brothers, creators of this podcast and several other productions. People love the awkward honesty of this kind of humor. It says: the McElroys aren’t suave, but they care a lot. This waffling reminds me of the kind of precious, neurotic type of narration I normally find in serious personal blog posts or in contemporary autofiction, in the vein of Sheila Heti or Ben Lerner. How should a storyteller be?

The McElroy brothers — Justin, Travis, and Griffin — are widely known for their 7-years-running comedy advicecast My Brother, My Brother and Me. In 2014, they established The Adventure Zone (TAZ) with their radio personality father after receiving positive listener feedback for a one-off RPG session. The adventure-comedy podcast brings together fantasy plot, radio show theatricality, electronica music, and RPG nerd culture. The theme song is a 1975 Mort Garson track featuring modulated synthesizers. The mood is casual and familial, with thousands of pieces of visual fan art available online. It’s a phenomenon that has widely outgrown its beginnings. And it’s teaching me a lot about engaging and meaningful storytelling.

It’s a phenomenon that has widely outgrown its beginnings. And it’s teaching me a lot about engaging and meaningful storytelling.

I’m used to books. I am used to literature being a perfectly-cast collection of words and signifiers, something I can mentally interact with and share with other people. What interests me about postmodernism, about autofiction, is the way these modes of thought deconstruct ways of thinking and play within already established rules and systems. Autofiction, for example, forefronts the construction of a self within the voice of a book’s narrator, mixing an author’s own life with the suspension of a character’s story. TAZ forefronts the construction of fantasy selves in a similar way. The fantasy characters are a mixture of fictional backstories and real-life decisions and interactions. But that construction and deconstruction isn’t stuffy or precious or trying to prove itself smart. Its overarching fantasy narrative is accessible and funny. And it entertains over the course of a long-term telling as a novel does — something that is harder and harder to do in this digital age.

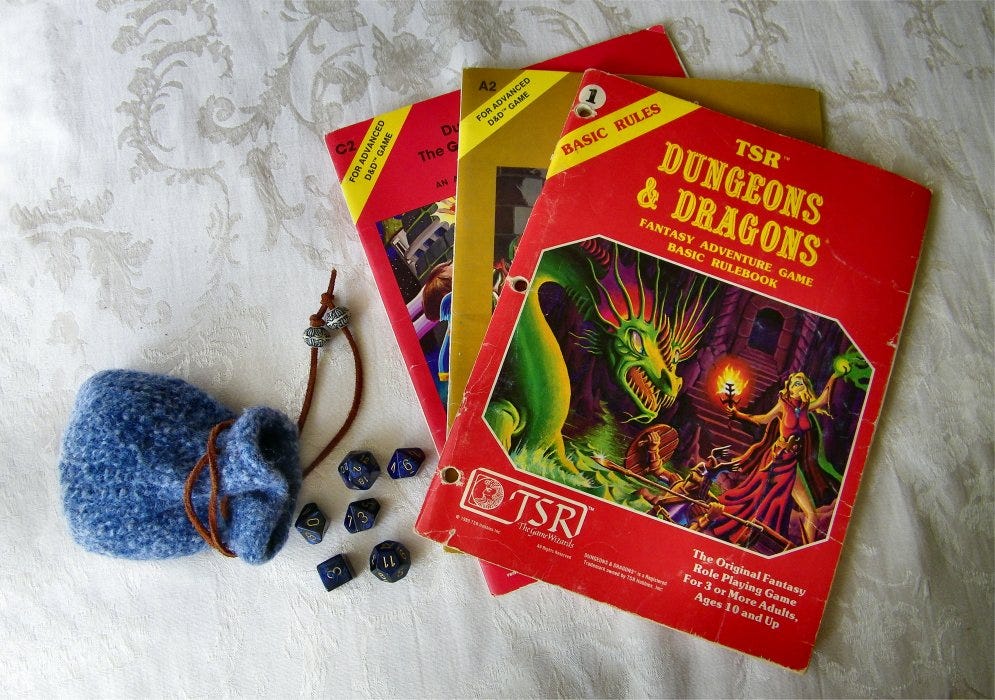

Role-playing games (RPGs) are essentially long-form make believe. They are interactive and collaborative storytelling games that can be employed in endless array. The specific tabletop RPG the McElroys use, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), is widely regarded as the most commercially popular RPG. If one digs through the literary influences on the creators, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, one finds evidence of the worldbuilding of Fletcher Pratt, the spellcasting lore of Jack Vance, the surreal horror of H.P. Lovecraft, and the epic questing of J.R.R. Tolkien. In 2013, Tor.com hosted a digital series of Advanced Readings in Dungeons & Dragons to investigate over 25 different authors Gygax and Arneson most likely drew from when constructing the RPG in the early 1970s. The different classes of character you can play as — barbarian, druid, wizard, etc. — are pulled from mythological and literary sources, from pre-Christian Celtic traditions to the character of Aragorn in the LOTR universe. Geographical planes where one can play, magical spells and weapons one can use, and monsters one might fight stem from sources as disparate as Pliny’s Natural History, Paradise Lost, and Arabian Nights. This kitschy mix of every fantastic invention or story we know of makes the texture of D&D campaigns collage-like and chaotic. Since so many ideas are being reused at once, one inevitably creates a new Frankenstein’s monster of a campaign every time. The chaos is controlled by the intricate set of rules and guidelines set up by Gygax and Arneson in the first edition of the game, which has been repeatedly revised over the years.

Since so many ideas are being reused at once, one inevitably creates a new Frankenstein’s monster of a campaign every time.

To begin scenes, Griffin as Dungeon Master (DM) narrates settings, drives the plot, or introduces new non-player characters (NPCs). His role is to moderate player action and mete out plot-relevant consequences, as well as set scenes and guide overarching plot arcs. In various episodes, he describes a pink tourmaline cave with contagiously growing crystals, a monstrous purple worm that erupts from beneath dry earth on a Groundhog Day time-loop, or a guardian homunculus composed of a clay-filled suit of armor. These expositions are set in stone, as descriptions of scenery might be in realist novels. Clint, Justin, and Travis are the readers of the story Griffin spins, but they are also storytellers themselves. Their characters (Merle, Taako, and Magnus) can act however they wish, or feel emotions just as Clint, Justin, and Travis describe. Their narrative power is partially limited by the randomness of dice; the players might describe what their next action could be, but ultimately the success of their action depends on how high a number they roll, and how it shapes up against various modifiers controlled by the DM. For example, if Merle starts to fall off the side of an elevator platform, he has to make a dexterity saving throw of the dice to determine if he can grab onto the edge.

Importantly, Griffin can only enter the characters’ minds in certain moments of exposition. It’s a weird conditional omniscience that is instructed by trust, a trust in the promise that all four “writers” will tell the story in the most fulfilling way possible. It resembles the simple game where friends go around in a circle, adding a word at a time to build a sentence. In this way, when I listen to the podcast, I don’t think about what “the author” is doing (which is the way I sometimes think when analyzing novels, despite what Barthes has said about the author’s vital status). Instead, I marvel at how the story organically grows. Because control is centered outside the locus of any one person, the story feels very alive.

It’s a weird conditional omniscience that is instructed by trust, a trust in the promise that all four “writers” will tell the story in the most fulfilling way possible.

RPGs as a medium are inextricable from metafiction, which makes it an ideal genre to examine how storytelling functions. This is due to the fact that, in an RPG, the narrators of the story are the authors speaking in character persona. This seems like all fiction at first glance — isn’t Pale Fire just Nabokov narrating as an obsessive scholarly persona? — but the importance lies in the immediacy of the story. There is no filter of voice or structure or even an editing process to screen the RPG authors from their readers. There is no script. All of them are in the same room, digitally or physically. And consequently, the “writers” of TAZ are constantly talking about their own “writing.”

Take, for example, Clint’s expressed appreciation of the elevator-vine escape scene. There are many levels of narrative intersecting here: Clint as player is caught up in the imaginative visual the four of them have conjured up; Clint as father is excited about the story his family is crafting; Justin as podcaster is hyperaware of what does not make good audio content; Griffin starts spoofing on the idea of in-text evaluation via cultural references. The site of this intersection is not just waffling — it still counts as the “text” of The Adventure Zone.

The site of this intersection is not just waffling — it still counts as the “text” of The Adventure Zone.

There are other moments where Griffin as main narrator can become a kind of “vengeful god” in control of the narrative, especially since anything that’s said aloud counts as the story. When Merle tries to pry open the door of the elevator shaft to assist Taako and Magnus, Clint-as-player gets carried away with Griffin’s sense of narrative power. As he chooses his next move, vines crawl up the stairwell behind him. He tries to leverage this for dramatic flair, “so [he] can be a vivid storyteller, too.”

Clint: And I pry open the doors at the very last second. Heh.

Griffin, clearly grinning: At the very last second. Ok.

Clint, crosstalking: No, wait. No! No! No, no, NO!

Griffin: You pry the doors open to the elevator —

Clint, crosstalking: Not at the very last second, nope, NOPE.

Griffin: — and a wave of vines crashes into you from behind, knocking you forward into the elevator shaft, and the doors slam behind you.

Clint: Five minutes! Five minutes before!

Griffin: You didn’t get there five minutes before. You — so, you have fallen into the elevator shaft, make a reflex saving throw to see if you can grab onto your party.

Clint: At the last 30 seconds.

Griffin, laughing: So, make a dexterity saving throw.

Griffin gleefully forces Clint to reap what he sows. That is, he treats any language or narration the players speak aloud as gospel, per se. Speaking enacts the action; you can’t rewrite the story because you realize it was a misstep. This ramps up the narrative tension.

These power dynamics among author, player and persona can also go the other way: characters can outsmart the DM. One major component of D&D play involves “leveling up” your character or purchasing magical items to assist you in your quest. For the purpose of making this rather legalistic process more palatable for listeners, Griffin creates Fantasy Costco, where the players can purchase magical items suggested by listeners. As a joke, Griffin allows an item created by the 8-year-old son of a listener to appear on the show in one of the first few episode arcs. It’s called the Flaming Poisoning Raging Sword of Doom, and it’s a deus-ex-machina of an item because, as an extremely powerful weapon, it would destroy a lot of the practical stumbling blocks that make D&D quests epic and entertaining (such as hit point values and dice rolls, which keep game outcomes random). Griffin sets the price impossibly high and leaves it there as a hyperbolic joke, seemingly to never be bought.

As a joke, Griffin allows an item created by the 8-year-old son of a listener to appear on the show in one of the first few episode arcs. It’s called the Flaming Poisoning Raging Sword of Doom.

At a later Costco visit, however, Griffin introduces another listener-suggested item, The Slicer of Tapeer-Wheer Isles, which allows the owner to persuade another character to give them their most valuable possession. Taako quietly buys this object and then immediately uses it against the Costco shopkeeper to barter for the impossibly valuable Flaming Poisoning Raging Sword of Doom. In the podcast, you can hear the absolute shock and awe of Griffin, who puts hundreds of hours into engineering the show to be a beautiful narrative, who tries to stay ahead of his brothers and father as DM, and who was out-thunk by one of the players. Even though allowing Taako to play the Slicer against the shopkeeper puts the DM at a disadvantage, Griffin feels an obligation to let Taako get the sword anyway because of the rules of narration and a trust in his fellow storytellers. It’s also just an incredibly comic moment.

The Self at the Bottom of the Toilet Bowl

In a behind-the-scenes episode released in March, Griffin admitted how much the story is affected by this constant struggle for narrative control: “The biggest thing I struggle with as DM […] is how much control over the whole narrative, the macro-narrative, do you give the players, and how much do you keep for yourself.” The show is thrilling because of this balancing of narration. This creates delicious dramatic irony, when the players know things their characters shouldn’t, or when narration needs to be juggled around to make sense. In fact, the best moments in TAZ occur when the DM is caught off-guard by a player’s choice, or the players learn something about the world that destabilizes the fiction they’ve created. As a young writer, I feverishly consume this kind of drama, and struggle with how to depict it in my own writing. Because I know good storytelling when I hear it.

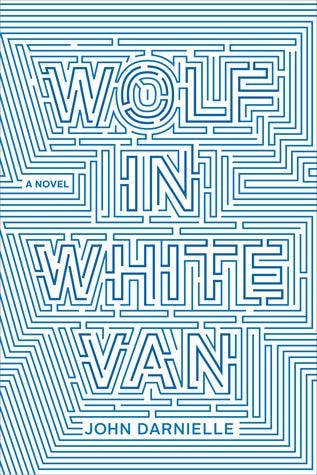

Wolf in White Van, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2014, is a novel written by John Darnielle about the master of a role-playing game. In it, the fictional world of the game is destabilized when two players confuse the game with reality. The novel’s narrator, Sean, is a fiercely imaginative young man who dreams of epic survival. After a violent head injury, Sean is cut off from most human interaction, seeing no one but his parents and nurse. In place of public interface, Sean designs the world of Trace Italian, which he advertises as an RPG ($5 per month gets you four mail-in “turns”). He builds a customer base, and ends up running the game for several hundred mail-in players. The goal of the post-apocalyptic RPG is to reach Trace Italian: the last safe fortress in an irradiated world raw and unforgiving. Each player’s story is different, because each choice they make takes them down a different branch of the game-narrative Sean designed. For each “turn,” he sends the player a description of the adventure’s latest development, ending with a series of actions the player might take.

The second-person narration of Trace Italian resembles the D&D narration that Griffin provides for TAZ, but in Sean’s consciousness there is a greater sense of desperation:

Where the railroad used to run, there’s a little less overgrowth. As you travel, you keep your eyes on the ground ahead of you, trying to make out a path. Hours turn into days. You become a human bloodhound. You notice things others didn’t as they tried and failed to walk the path that now is yours. As you progress the path becomes less clear: with every less clear point you know you’re going beyond the places where the others lost the trail. Stopping to rest, you see a spot where plants seem to grow higher. If they have followed your path faithfully, bounty hunters will be here within the hour. North lies Nebraska. […]

FORAGE FOR ROOTS

FOLLOW THE RAILROAD

WAIT FOR HUNTERS

NORTH TO NEBRASKA

The player then mails back their response. Sean notices that players tend to explicate much more than necessary — they become deeply involved with their characters, to the point of being one and the same. That’s the whole point of the game, anyway: to suspend reality and become that desperate character. For Sean, these RPG exchanges become the communication and human sustenance he clearly craves. He admits how deeply he identifies with the playing character: “Every move I send out begins with the same word: You. When I first wrote most of them, so long ago now that it’s incredible to think of it, I had in my mind only a single player, and of course he looked almost exactly like me […]. I was building myself a home on an imaginary planet.”

Two players named Lance and Carrie take Sean’s instructions extremely seriously — they carefully plot each move they make as a pair. As the game progresses for them, they begin to believe that the Trace Italian is real. The two of them collaboratively construct a new reality together, and this belief turns out to be fatal. In the novel, Sean struggles with the idea of Lance and Carrie’s infatuation, but he also seems to understand why they fell for their own illusion. RPGs have real power.

In the novel, Sean struggles with the idea of Lance and Carrie’s infatuation, but he also seems to understand why they fell for their own illusion. RPGs have real power.

This power is investigated in a scholarly article in the journal Symbolic Interaction, “Role-playing and Playing Roles: The Person, Player, and Persona in Fantasy Role-Playing.” In addition to years spent playing D&D in their own personal time, the authors (Dennis Waskul and Matt Lust) took observational notes on D&D sessions held near them to build a critical argument regarding self-building and personas. One of their big sticking points is the idea that the gameplay interaction that takes place during a D&D session is seen as almost enchanted to the players — that the characters they play must be kept different from their actual real-life selves: “role-playing sessions are ephemeral situations encased” by “symbolic boundaries” that separate societal roles from gaming roles. This kind of reverence, the authors argue, is what allows players to create a kind of liminal space where character (and thus self-) creation can occur, because as much as players might try to separate themselves from their characters, that persona nonetheless absorbs your own characteristics. This self-creation is what caused Lance and Carrie to delude themselves; they lost sight of the boundaries of reality and fiction.

The McElroy family hardly ever pretends to follow boundaries. They center their comedy on the idea of failing to be that sacred or precious about their roles. Instead of veering toward seriousness, though, they veer toward humor. They mock one another persistently, and even playfully mock the few that object to their devil-may-care approach to D&D. At one point, Griffin pointedly declares that he has noticed some D&D purists tweeting that elevators would be anachronistic in a D&D fantasy setting. In response, he adds elevators as often as possible, and even sends the characters to a museum-like room called “The Magical World of Elevators.”

They center their comedy on the idea of failing to be that sacred or precious about their roles. Instead of veering toward seriousness, though, they veer toward humor.

For them, it’s not about an escape into a fantasy world, or the bizarre ability to conjure up an enormous avatar of Della Reese as a temporary guardian (something Merle does at one point). It’s the joy of creation and play. The imaginative power of TAZ lies not necessarily in the players themselves, but in the community that’s sprung up around it. I sense the power in the thousands of pieces of fan art, depicting each of the many fantasy characters in dozens of forms. I sense it in the hundreds of animatics uploaded to Youtube, where talented young people test out animation skills. I sense it in the extensive lore the fans create, tracking connections and plot developments in wiki pages and on personal blog posts.

In studying the history of literature and the implications of contemporary fiction for the past several years, I think I lost sight of the wonder of storytelling. Yes, my appreciation of the transportive abilities of fiction has always been there, driving me to learn more about how writing works and what it offers to human culture. But I began to think of storytelling as a sort of idealized miracle-working, something with a secret that I had to work for ages to uncover. The Adventure Zone has taken apart that belief, and rebuilt it in the form of something much more communal and welcoming. Part of TAZ’s success comes from its oral medium: it feels like improvisational theater, and it’s easily consumable as a podcast. But most of its storytelling value comes from the immediacy of its creation, the kind of joy that stems from spontaneous narrative. I feel as if I am down in the dirt with them as these four authors assemble the story. I feel that this is how a storyteller should be. Or at least, the kind of storyteller I want to be. The McElroys would laugh at my praise, but that’s because they know how to play. To take themselves seriously would ruin the game.