Interviews

Enjoy Your Characters. They Might Be Famous One Day

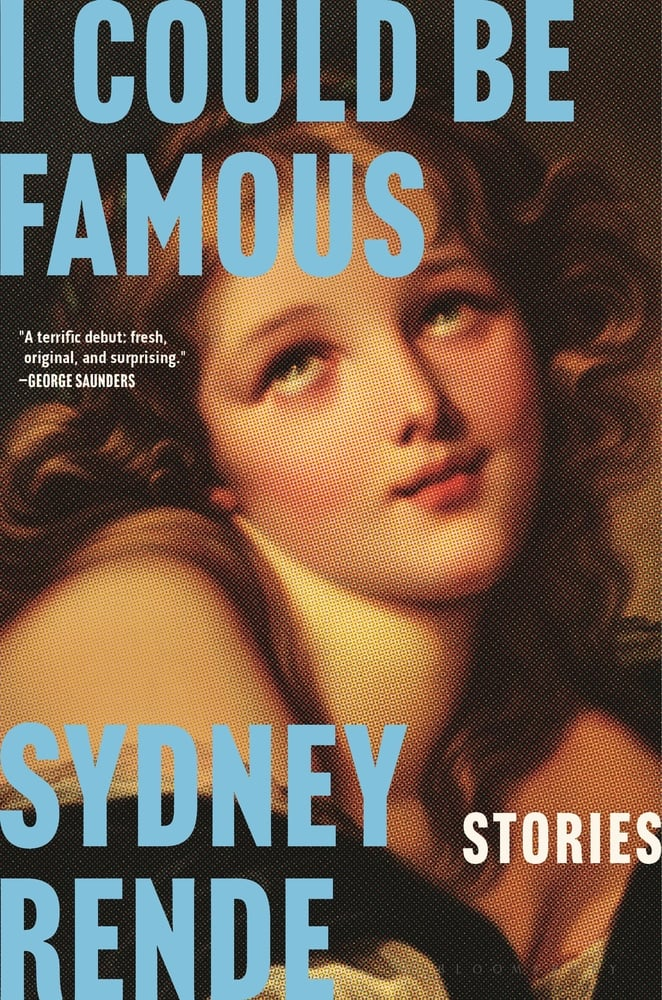

Sydney Rende’s “I Could Be Famous” plays with the fantasy vs. reality of modern-day fame

Fame used to be something sacred. Back before the internet shattered monoculture into millions of digital pieces, “celebrity” was a title held only by the saintly and untouchable few. The 50s had Marilyn Monroe. The 80s, Michael Jackson. The early aughts, Britney Spears. Try and think of a celebrity that’s defined the 2010s or 2020s, though, and your options are suddenly endless. Might we say, the YouTube star MrBeast? Or maybe the Instagram behemoth, Kylie Jenner? Addison Rae of TikTok fame? There’s also, unfortunately, Elon Musk on Twitter. And—I just looked this up—Lenny Rachitsky, who is apparently the most followed user on Substack. It seems like they’re making just about anyone famous these days.

Sydney Rende’s debut short story collection, I Could Be Famous, is astutely aware of the participation prize that fame has become in the twenty-first century. Read the title out loud and you realize it’s true—you, yes you, really could be famous. In a world where just about anyone can turn a snappy catchphrase into appearances on daytime television, or milk thousands of dollars off of ten second dance videos filmed at home, we’re all technically on the edge of having our lives forever changed. The question, though, is should we?

With a magnetic, fresh voice and an acidic sense of humor, I Could Be Famous dares readers to question the Hollywood Walk of Fame and the trending tab on social media as sites of modern worship. Between hot-shot superstars accused of cannibalism and absolute nobodies turned kleptomaniacs desperate to feel something, Rende tracks our obsession with mass perception as well as our complete unpreparedness for what said perception means for our feeble little lives. Over Zoom, Rende and I discussed LA vs NYC culture, the inclusiveness of modern fame, reality TV-induced delusions, and humor as a way to get close to people.

Jalen Giovanni Jones: These stories feel incredibly Southern Californian. I see it in the rich descriptions of Los Angeles, yes, but also in the characters’ voices—there is this breezy flippancy that is both hilarious and also immediately recognizable. Is there something specific to the culture of Southern California that made you want to focus this collection largely in that region?

Sydney Rende: So many things. I really feel like I should have been born in California. A lot of these stories, and the narrators of these stories, are really just iterations of my own voice. The stories are set in and around LA, and I have such a wild relationship with LA. I’ve visited a ton because I find it fascinating. When I went to LA for the first time, I felt like I was stepping into a simulation. The whole city is so nostalgic for its own past, especially architecturally and culturally, but at the same time it’s so modern. It makes for the best people watching I’ve ever seen. My dream party is one in Los Angeles, where I’m wearing an invisibility cloak and just walking around observing people, seeing what they do when they think no one is paying attention.

People are drawn to LA for very specific reasons, and those reasons really interest me, especially when it comes to fame. The nature of fame is so fluid and changes so much that I’m really drawn to people who, even now, are still after it and romanticize it. And LA is the city that romanticizes fame and celebrity the most. NYC feels like a very serious, hardened place. LA feels very much the opposite. For that reason, I just think it’s a really good time.

You can be really famous and still living in your parents’ house these days.

JGJ: About LA’s simultaneous nostalgia and futurism, I’m wondering if you find that fame operated differently in the past, versus how it operates currently.

SR: Definitely. I grew up obsessed with Perez Hilton and reading Star Magazine and Teen. When we fantasize about fame, it’s often the kind of fame from about 30 years ago, where it was reserved for movie stars and rock stars who were famous for very significant reasons and beloved. Fame now is really different. It’s so much more accessible. There are more famous people now than there were 30 years ago, and “fame” is diluted because of that. It’s very, very fleeting. Most people who crave fame are romanticizing based on the way that fame used to be. Then, because of social media and reality TV and all that, they actually become famous—and maybe are not as prepared for it as they assumed. Celebrities from the past were a little bit shielded from the public. Now, there’s online commenting, DM-ing, and all these ways to access people who are well-known. Also, if you were really famous in 1995, you probably had a ton of money. That’s not the case anymore. You can be really famous and still living in your parents’ house these days.

I was very interested in writing about those people who have those deep fantasies, where ultimately dissatisfaction occurs, where they realize what they wanted isn’t actually real. Fame is now something else entirely. They can’t attain that old, idealized version of fame. The new version of fame is weirder, is way more fleeting, and honestly, is more inclusive—and that makes it more interesting to me as a subject.

JGJ: An aspect of this collection that I really loved was your careful dispersal and withholding of information. You often left it ambiguous whether certain rumors were true or not, for instance.

SR: I don’t think you can really trust any narrator fully, especially a first-person narrator. They’re always hiding something from you. There are definitely certain characters to especially question, like Arlo Banks—is he eating people, or is he not?

JGJ: I read all of “Trick” believing he wasn’t. And then I got to the last line, and everything was thrown into question. That last piece of the puzzle made the entire picture look different all of a sudden.

SR: I’ve actually gotten a lot of criticism of that story, asking for it to be less ambiguous. But I think the nature of this type of situation—which is a satirical exaggeration of how rumors spread about a celebrity’s private life—is ambiguous. I really wanted to explore that ambiguity, and not have to come to a conclusion.

I’m rooting for all the characters that I write about, but at the same time, [Arlo Banks] is definitely bad in a lot of really serious ways. He’s not someone who I would want to hang out with. I got a lot of feedback from people saying “I don’t know if I like this guy or not,” and my only answer is, “me neither.”

JGJ: The character of Arlo Banks specifically reminded me of Claire Dederer’s Monsters—that book, like your stories, dissects the relationship between fans and famous artists that are seen as bad people. Do you feel it’s possible to separate the art from the artist?

I don’t think you can really trust any narrator fully, especially a first-person narrator.

SR: I think a lot about that question too, and there are so many artistic people out there who deserve recognition, who are doing really good work, and who also aren’t terrible people. There are definitely great artists who have done bad things, but I’m in a place right now—especially considering how the world feels so scary these days—where I’m like, “Let’s appreciate the artists who are doing good things too.”

JGJ: Did writing I Could Be Famous change how you saw yourself as a consumer of reality TV and social media?

SR: Definitely. I don’t actually watch much reality TV anymore. I’m not nearly as invested as I used to be, but I may just be aging out of the generation that’s on TV currently. Writing these stories, I got into the mindset of characters who are really obsessive and stalkery. I’m realizing as I’m writing them that these are coming out of my brain; this exists in me. You watch a reality show for 10 years, and you start to think that these people are your friends. But you don’t know them.

It was the first story in the collection, “Nothing Special,” about a girl who befriends an influencer and comes to believe that she’s her close friend—that totally came from a place of me believing deep, deep down that the people on these shows were my friends, and that we would get along famously if we met. And then taking a step back and realizing that’s totally delusional.

JGJ: There’s an undeniable sense of humor that’s very prevalent throughout the book. How do you go about balancing that humor and accessibility while also maintaining the stories’ high literary quality?

SR: Humor is my favorite form of entertainment. Two main things my writing professor George [Saunders] would say were, “Does this sentence make me want to read the next sentence?” and, “Am I entertained?” You can tell when a writer is entertained while they’re writing. My goal when I was writing these stories was always to keep myself entertained, and if I ever felt myself getting bored that meant the reader was going to get bored too—so I needed to change it up somehow.

You watch a reality show for 10 years, and you start to think that these people are your friends.

I’m drawn to humor because I think you can learn so much about a person (and character) from their sense of humor. It helps you relate to them. I really wanted to enjoy my characters’ company. Otherwise, I would be bored and I wouldn’t want to write. So even if they were bad or doing ridiculous things, or not likable in one way or another, I made sure that people wanted to hang out with them through humor.

JGJ: I was impressed by how prevalent the internet and screens were in these stories—people are on social media, they’re checking headlines on phones—and yet the pacing always felt swift. How did you keep the stories moving forward, even while they bounced between the analog and the digital so often?

SR: I actually struggle with pacing a lot, and I think it all comes down to revision. The pacing of a story for me is always messed up the first time around. You can tell where I’m getting bored, or where I want to speed through something. The revision is the only way to get your pacing right.

I took out a lot of the screen stuff because I was like “we don’t need her to call her mom right now, something else physical can happen.” A lot of the screen stuff is the nature of the content. If you’re writing about fame between 2019 and 2025, it’s kind of hard to avoid an iPhone or some kind of app or a headline. That part just comes with the territory. But I like to try to keep the stories as evergreen as I can—so not depending too heavily on Instagram or other fleeting apps and digital stuff that could be really huge right now, but in 10 years could be non-existent for one reason or another. So I thought about that a lot too—not depending too heavily on specific, modern digital stuff, and trying to keep it person to person as much as I could. If you wrote into a story how often we were truly on our phones these days, I think it would be so boring. There’s a little bit of fantasy, at least in the stories that I write, in how the characters are not attached to their phones 100% of the time. I think that’s a flaw in who we are as people now.

JGJ: Would you like to be famous?

SR: I have thought about this a lot. No, today-me, no. I fantasize about being like a rock star in 1970, but in that scenario, I’m not me, you know? I’d be somebody else. I’m afraid to be famous. I love watching other people.