Interviews

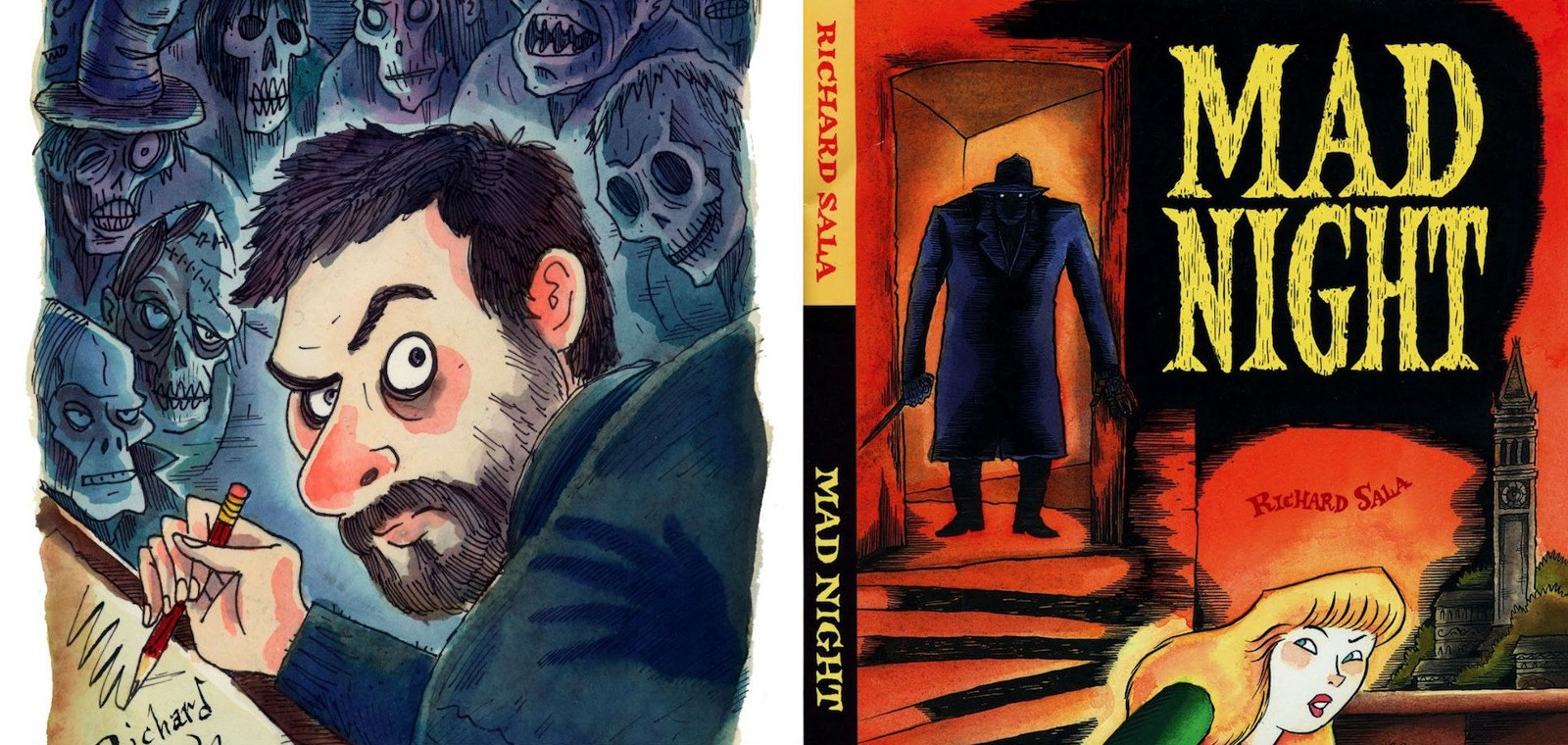

Every Speck of Curiosity, Fear, and Gloom: a conversation with Richard Sala

Richard Sala’s books may feel out of place in the modern world of comics and graphic novels, and there’s a reason for that. His storytelling sensibilities come from a mixture of influences ranging from surrealist filmmakers to gothic artists to campy heroines like Emma Peel and Barbarella. If Sala is reinventing his childhood fascinations, he may be no different than many artists, but set his work next to any other comic and you will see it stands out from the crowd.

I have been a fan of Sala’s visual style and entertaining mystery romps for a long time, going so far as to track down a copy of the out of print Doctor Sax and the Great World Snake, by Jack Kerouac published by Gallery Six and illustrated by Sala. His work feels both vintage and fresh, a nod to its influences while managing to stand on its own. His work is instantly recognizable as his, perhaps the greatest benchmark of an artist.

Ryan W. Bradley: Your work is a cross-section of fairy tales and classic mystery cinema, the obvious comparison being Franju’s Judex (with a splash of The Avengers’ Emma Peel), which itself was a remake (the second, in fact). This melting pot echoes the interwoven nature of visual and textual storytelling inherent to the comic/graphic novel form. What interests you in this pairing of influences, what do you look for in telling these stories that have become the hallmark of your career so far?

Richard Sala: The element that appeals to me in a lot of what has influenced me over the years is kind of a willful sense of the absurd. It’s certainly on display in The Avengers TV show, but also, more subtly, in Judex, which flirts with surrealism (bird head masks, for example). It’s an element that might be variously described as “tongue-in-cheek,” “over the top,” “delirious,” “surreal,” “expressionistic,” “bizarre,” or even “campy.” What it is, most of all, is a lack of interest in realism or the mundane. From a very early age, I only related to the world with a sense of the absurd and black humor. For example, I suppose I can understand the impulse in so many people to want to make a story about a guy who dresses up like a bat to be dead serious and heavy — but that’s just not for me. It only makes sense to me if there is an embracing of the ridiculousness of the concept. I love mystery and horror — — all kinds — but when I sit down to write it always tends to veer toward a kind of silly fun — but silly fun with a dark side and a mean streak and a sense of the unreal. I think that’s because my formative years were the late 60s and early 70s — and that kind of humor (black comedy, spy spoofs, Barbarella) was everywhere. A good example of that kind of thing is the recent rerelease of Jodelle from Fantagraphics Books.

RWB: Absurdism gets discredited sometimes or dismissed as being over the top or ridiculous, but as a style it has been forgotten by many that its roots are in philosophy, that its cousins are existentialism and nihilism. Absurdism can be just as effective at examining the world as realism. For instance, you mention looking at the world only making sense in regard to this black humor, whereas for some people it’s purely escapism. Do you think that early predilection led you toward creativity, toward a more artistic path in life?

RS: Oh, yeah. The desire to create often comes from yearning for something that you can’t find — or longing to recapture a feeling you once felt. I wanted to be either an artist or writer early on, and in my teenage years I was interested in all kinds of genre stuff, so that’s what I tried to do. But I struggled to find my individual voice in that world. I just couldn’t do it with a completely straight face. I did these deadpan stories inspired by affection for old time thrillers and serials — tongue-in-cheek, but without any real parody or mockery. Some people would scratch their heads. I just wanted them to be fun! If anyone read my early Dark Horse comic “Thirteen O’Clock” or saw my MTV cartoon “Invisible Hands” — that’s what I mean. It’s similar to the way the 1966 Batman show was written, if it had been a lot darker, with words that could have come out an old comic book verbatim but presented in such a way that lets you enjoy it on an entirely different level. I guess that’s why I feel a kinship with “camp” humor, because it was everywhere when I was a kid.

RWB: Do you find yourself drawn into stories or characters first when creating a new comic or book? I wonder how this differs (or stays the same) from writers who work only in words. I imagine there has to be more forethought and planning, less stream of consciousness in creation, which seems like it would lend well to character development early on.

Logic, research? — I’ll worry about that later.

RS: I’m actually a great believer in letting my stream of consciousness take the wheel — at least initially, to get the thing flowing. I’ll often just start with some situation or set piece that has occurred to me in some flight of fancy. Then I’ll worry about building a plot and characters around it later. Logic, research? — I’ll worry about that later. The initial inspiration is usually a purely visual thing. I think creating comics is more analogous to making movies than writing books, so I often think in terms of a sequence of events, and concocting a set piece.

Drawing can be a lot of work, so it’s important to keep yourself interested and entertained, too, if you want your audience to be. I like the idea of creating bizarre circumstances just by combining elements that aren’t often combined. Like, what if a bunch of assassins had a confrontation in a closed zoo after midnight? Or, what if you were at the botanical garden and all the plants turned out to be carnivorous? Then I’ll build a section of a story around that. None of those kinds of things are necessary to the plot, but they keep things lively — and for me they keep the fun of creating alive.

RWB: I love the idea of stream of consciousness playing a role in your work. And as a reader I would most definitely think cinematically before connecting comics to written work in terms of creation. I think I tend to approach my written work similarly though, which leads to very concise prose and a focus on moving through the plot. How much of the story do you have in place before you start diving into the work of drawing and writing, or do you allow for the story to evolve as you begin working sequentially, as a writer might? What kind of evolution in your plots and characters helps spur the project along?

RS: I follow the outline of the plot I’ve written out which is pretty linear but also kind of sketchy and flexible, so I can allow the story to evolve along the way. I’m usually only certain of the very beginning (the words or images that kick off the story), the very end (though that can change) and one or two set pieces I want to incorporate into the story. And that’s all. I like to be able to let everything else develop as I go along.

With comics, you have to pay attention to the rhythm and flow of the panels on each page. Each page should feel self-contained and also move the reader along so they’re turning the page before they even know it. In my longer books I try to alternate the pacing — moving from slow, atmospheric, shadowy scenes to sudden bursts of craziness or delirium.

RWB: I’m interested in how this intuitive form of development translates to your characters. Many of your characters are female; in fact you have a folio book forthcoming that is all portraits of “dangerous” female characters, each of whom would be a natural fit in one of your stories. Do you make conscious decisions about your characters in terms of gender? What makes you gravitate toward female protagonists? It’s one of the aspects of your work that really stands out, that is unique in comparison to a lot of other comics out there, which is an increasingly important debate in the comic community as a whole.

RS: Yeah, long before it was an “issue” of any kind, I was baffled about the lack of interesting female characters. Maybe it goes back to my love of the Avengers TV show again where Emma Peel was such a strong and compelling character, who could be equally violent and witty, often at the same time. And I mentioned being influenced by the concept of Barbarella, too. Beyond the “sexiness” of the character, I liked the idea of a woman on a series of episodic adventures. She’d often be out of her depth, but always prevailed.

…I’m baffled when I watch a movie and in the cast there is only one major female character — I mean, literally, one single woman.

Then there was the influence of horror movies, where women are often the focus and plenty of times they emerge as the only survivor, due to cleverness and summoning a strength they didn’t know they had. I like the underdog aspect of that — overcoming the odds that are stacked against you. It’s weird — to this day I’m baffled when I watch a movie and in the cast there is only one major female character — I mean, literally, one single woman. Whose life has only one woman in it?

Besides horror, the other genre with multiple female characters who could be clever and ruthless or anything else were the many spy movies that came out of the 1960s. Those women were just as capable and dangerous as any of the men. So, yeah, I’ve had many lead female characters in my books. When I see all those ubiquitous articles asking why there aren’t strong female characters in comics, I have to remind myself that to most of the comics community and journalists, alternative comics are still mostly invisible or just unfathomable (although maybe it’s just mine!).

At least five years before the TV character Veronica Mars, I had my own updated version of Nancy Drew, named Judy Drood. Her story was originally serialized then released as the book Mad Night. She was also in a later book called The Grave Robber’s Daughter. Unlike the kind of bland TV character, Judy is extremely angry, slightly crazy and obsessive — I figured, why else would she pursue some maniac killer against all odds and common sense? She was a really fun character to write, but if I did a new book with her now, thanks to Veronica Mars, that whole concept seems played out.

I did a young adult book with First Second about a teenage girl cat burglar with kind of a grim back story and a few years later there was a similar character being published by another mainstream publisher to all kinds of awards and acclaim. It’s the same idea — a teenage girl cat burglar — but done “cute” with all the interesting, darker edges sanded off. Fine, but I can’t do another story with that character now because it will seem like I’m copying them. I realize that it’s all just pop culture, and it’s all out there for the taking. And I know that my work might be kindly called “an acquired taste” for many people, so I’m never surprised to see ideas I’ve already done being used by others with much more success. I’ve taken plenty of things from pop culture, myself — but I always credit my influences, because I love them. I’m still a fan at heart.

RWB: It definitely seems like the lack of female characters is a much bigger problem in superhero comics than in the more independent comic world, but even there, a lot of that growth has seemed to come in the last decade. I know when I was an undergrad and in grad school there was a lot of talk about men writing female characters, etc., and when men say, “well, I can’t be in a woman’s head,” my thought was always, we all have mothers, lots of us have sisters, and all of us have known plenty of girls and women in our lives, why not start there. Do pieces of people you know and have known find their way into your characters, do autobiographical tidbits factor in, as they often do for fiction writers, even though you’re telling stories that aren’t “realist”?

For me, it’s more of an exorcism of personal demons than an attempt to empathize with fictional characters.

RS: For better or worse, I’m not one of those writers who say “my characters take on a life of their own and do whatever they want and I just listen to them until I slowly understand who they are” and so on. I don’t write those kinds of stories. Sadly, my characters are pretty much all me. Every story I write and draw has the same “voice” and it’s mine. Every speck of curiosity, fear, fortitude, nastiness and gloom is conjured up out of some corner of my own brain, some darker than others. For me, it’s more of an exorcism of personal demons than an attempt to empathize with fictional characters.

My characters are all little psychological self-portraits to some degree, men and women. But, yes, it was certainly helpful to have had a mother and sister and many women friends in my life. I’m glad I went to art school where I met some of the most complicated and interesting women in my life. In art school, everyone lets their boundaries down a little, and, in those pre-internet days, it was one of the places I’d hear really personal stories about what women have to face on a daily basis in their lives. So, yeah, that helped. The personality of Judy Drood (my short-tempered girl detective) in particular is based on this wonderful, hilarious, strong, angry woman I knew who was a grand contrarian. She was like that Groucho Marx saying of not wanting to be a member of any club that would have her. She always “flipped” the script and surprised people. She simply couldn’t stand anyone agreeing with her about anything. So I used that in writing Judy, who never reacts the way any cliché damsel in distress is “supposed” to act.

RWB: People tend to think less about autobiographical influence when they aren’t reading something that is packaged like a memoir or realist fiction, even poetry. This makes me want to go back and re-read your books. Another thing people tend to analyze less with comics is the writer/artist’s relationship with place. You are from California, but grew up in Chicago and Arizona, right? How have the different locales where you’ve spent portions of your life influenced your work, whether directly or indirectly?

RS: Oh yeah, “place” has been a very important factor for me in my work. I was born in Northern California, very near to where I live now, but my family moved to Chicago when I was three. I think of myself as a Chicago kid because those really were my formative years. I was pretty happy. Then we moved to Scottsdale, Arizona when I was in the 6th grade — in the middle of a school year — and I never felt like I fit in there. It was complete culture shock. It was like moving to Mars. I think that was the beginning of my (since) lifelong feeling like an outsider, feeling like I didn’t belong. I had friends, but it took a long time to adjust. Meanwhile, I’d always heard my parents talk about the Bay Area and I’d see pictures of when I was a toddler there, and I felt a strong connection. So, when I got the chance to move back in my twenties, I did. Moving from the Phoenix area to Berkeley/Oakland was like culture shock all over again — but in reverse of the first move. I felt like I wasn’t always struggling to fit in, like I had found where I belonged. So here I was able to look back and start to make sense of the alienation I’d been feeling for years and years, of always feeling like a stranger in my own town — and use them in my work. So I probably have my years in Arizona to thank for all the existential dread and anxiety in my work! I mean, I have good friends who love living there — but it just wasn’t for me. I even wrote one of my few semi-autobiographical stories based on living in the desert there: Here Lies RICHARD SALA: Desert Night Drive.

RWB: I had a similar experience, growing up in Alaska, then going back and forth between Alaska and Oregon, even little bits of time in upstate New York, Pennsylvania, New Mexico, and northern California. I have always felt closest to Alaska, though, and I probably spend way too much time thinking about it. As a result it becomes the focal point of my writing. However, your work feels almost place-less, as in it exists outside of a place we “know.” When I read your work, I’m not reading a California or Arizona story, similar to the way your stories feel timeless, they have a throwback vibe, but there is no need for a defined era. Is that natural or contrived when you set out to create a story? Do you think of your characters, places, etc. as existing in a particular universe or universes?

It’s one gigantic psychological self-portrait.

RS: Yes, and that’s because, once again, it’s all inside my head — the whole world of my comics and all the characters in them. It’s one gigantic psychological self-portrait. It probably sounds trite for a writer to say this, but the places in my comics are based on my experience with dreams. In my dreams (and it’s probably not like this for everyone), there are very specific places that I return to again and again — places that don’t exist in real life. But they aren’t fanciful places or surrealistic landscapes like a Dali painting. They’re rather mundane. I know the layout of a large sprawling town, many of the individual shops and a certain college campus and its various buildings, none of which actually exist. I’ve tried making maps — but I can only get so far because it’s always kind of elusive. The places in my comics are like that, though it wasn’t intentional at first. But, for example, throughout various titles there are references to certain places. It started kind of whimsically. I think “Dr. Erdling’s Crime Museum” may have been the first place I made references to in different books. There are a lot of little “in jokes” (I guess what they now call “Easter eggs”) throughout my books, threads that connect things in various ways. The book I’m finishing up right now, called Violenzia and Other Deadly Amusements, has a reference in it to a place mentioned in another book, which, if you spot it, gives a little more background to a character.

Also, I did put together an online reference guide to some of the cast of characters in my stories. It’s called SKELETON KEY. Each entry contains a portrait of the character and “biographical” information. It barely scratches the surface of all the characters that have appeared in my books, but most main characters are included (at least the ones who existed at the time I did the guide a couple years back) along with minor ones and others that haven’t actually appeared in any published stories yet. It came out of a time when I was looking back, taking inventory of my accomplishments, good and bad, and decided to put together a readers’ guide before I left the planet — in case anyone might be interested after I’m gone! Of course, it contains more than anyone would probably ever want to know, but, if nothing else, it was fun for me to put together. You can find it here or here.

RWB: I’m probably going to get lost in the art again looking for hidden meanings! I used to have a hard time reading comics, because I would focus so much on the art I’d forget to read the text.

I think writing can be like acting. There are the method writers who really delve into the characters, who know them inside out, could tell you their birth-dates, etc. And then there are writers who get a feel for the characters as they go along, and don’t feel the need to know what each particular character got for his or her fifth birthday. I’m in the latter camp, but oddly when I thought for a brief time that I was going to go into acting, I was very much into the method side of things. This is all to say, does all this character development come naturally with the writing process for you or is it part of a preparation that goes into it? Do you learn more about a character’s backstory as a story you are telling progresses?

RS: Yeah, I think you embody the character while writing the story. That is, you’re inside them, like an actor, so when they face a certain situation, you know instinctively how that individual character will react. I tend to write my characters broadly and with tongue in cheek, so the way they react is where the humor comes from often. They don’t react in any kind of realistically believable way — there’s no entertainment in that, if everyone is always reacting to danger by calling 911 and waiting for the cops to show up. On the other hand, who needs another character reacting like a clichéd superhero or hard-boiled detective? Everyone’s already seen that a million times. I try to find some new direction to go in — but that’s more to keep myself from getting bored. Because I get it that people like reading traditional superhero or hard-boiled crime stories — I like them myself. But I’d get so bored if I had to write my stories straight, if I took them too seriously. I have to have fun writing the stories, or else, why bother? At this point in my career, I’m not winning any major awards for my work — and I couldn’t be less interested in that. So, I may as well just continue writing the kinds of stories my readers have told me they like.