Lit Mags

Everything You Want Right Here

by Delaney Nolan

AN INTRODUCTION BY HALIMAH MARCUS

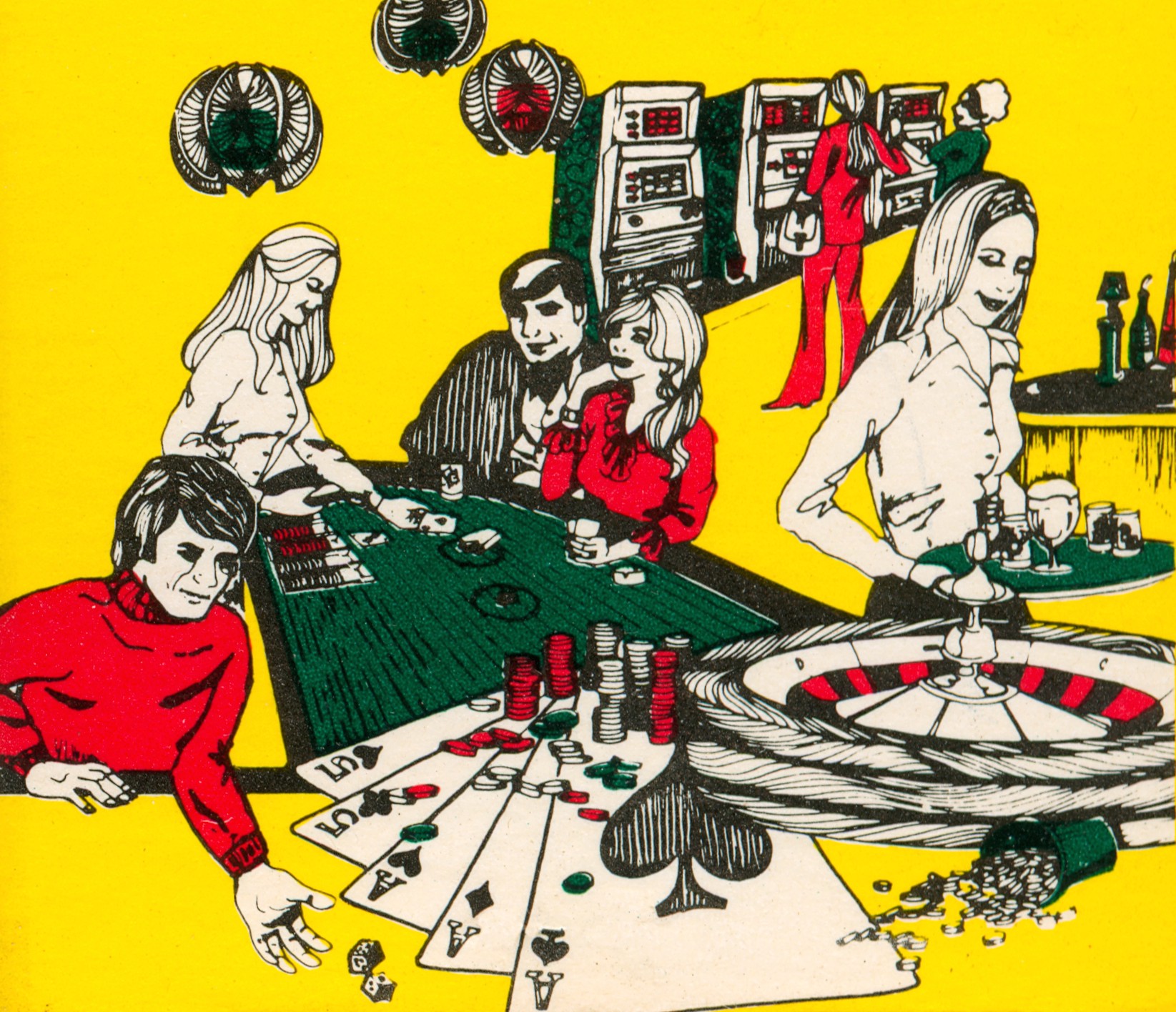

In my life, I have spent two nights in a casino. Both filled me with existential dread. The first was with a group of friends whom I barely speak to now, and our falling out seems somehow a result of that evening. As if those needless fourth, fifth, and sixth drinks, those people movers and badly carpeted corridors, those mazes of machines, those over-priced buffets, and that hangover that was more like a moral reckoning, had poisoned our friendships. It’s magical thinking, I know, that the casino was to blame. But on the other hand, how could it not be?

That’s the anxiety I bring to Delaney Nolan’s excellent short story, “Everything You Want Right Here,” about a married couple living for the foreseeable future in a casino called Les Sables. Outside there is desert and more desert, filled with endless sinkholes or possibly one giant sinkhole, threatening to swallow them with its granular, open maw. Inside is an adult playground, hermetically sealed and filled with confections. The Les Sables Casino is like the world’s largest cruise ship if it never docked; every you need is indeed right here, if what you need is a fountain of cane sugar and never fresh fruits or vegetables.

Our couple, Natalie and her husband, are among the lucky ones, winning big in the first act. (A jackpot at the slot machine gets you a rare tomato plant.) But the casino life may be poisoning them too, and Nolan writes their lives playfully and imaginatively, with the occasional gut-punch of insight. “I felt a twist in my stomach,” thinks Natalie’s husband. “I could see that she was lonely and that she wouldn’t tell me about her loneliness. This is a terrible thing to know about your wife.”

Natalie’s loneliness might also be called longing, not for her tomato plant or to be outdoors, exactly, but for there to be an out of doors to begin with — a place she might go to find something she doesn’t have, should she ever need it.

The second night I spent in a casino, I was practically a pro. When claustrophobia threatened to set in, I located the exits. I mapped the floors and learned my way around. I alternated alcoholic beverages with fizzy water. Like Natalie’s husband, I developed a system. He explains, “At some point around last year I started holding on to leftover bits from meals, just to remind myself: time is passing, time is passing. This is your life. It really is.” I wasn’t carrying around leftover foot in my pockets, but I had reached a state of acceptance. When it came time to check out, I was ready, but I also could have handled another night.

Halimah Marcus

Editor-in-Chief, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading

Everything You Want Right Here

Delaney Nolan

Share article

by Delaney Nolan

Natalie was pulling the slot machine lever, dropping in coins from a little yellow purse she held in her lap. I was drinking my fourth daiquiri, which was also yellow.

“This honestly tastes like real bananas,” I said.

Natalie said, “I think you must be bad luck today.” She held the lever until I took two big steps back. Then I took a third step back. Then she finally let go of the knob and the slots display spun its crazy numbers. You’d think that would’ve shown on her face, but we were all in the same romantic forever twilight of the casino, and in the reflection on the plastic she looked bored, like an angel. Her hair was big, full of that funky-smelling hairspray: shiny, flammable, rough to touch.

We were standing near the one window in Game Room Twelve, which was tinted dark but still showed the red desert going on outside, the same for miles, thousands of miles, I guess. Jermy, who works janitorial on our floor, told me once that the desert led to a massive sinkhole, that magnificent quantities of sand were pouring into the sinkhole day after day, and that eventually we would pour in, too, all of us, the casino and the games and the residents and everything. But that is ridiculous. There might be one sinkhole. But we can’t be surrounded by sinkholes, not in every direction. Statistically, we’re going to turn out fine, in the long run.

Then there was a bright ding! and Natalie whooped because she’d won: out of its mouth the machine spilled a waterfall of shiny tokens, each one small enough to fit in her palm. She said, “I’ve never played this game before,” and applauded a bit, folding her one free hand over and clapping her own fingers, before adding, “not in this room, anyway — not this machine, at least.”

“Do you want some breakfast?”

“I’m not really hungry.”

I peeked over her head toward the lobby. “Did you see the fountain of cane sugar today? It’s really going.” I put my hand flat against her shoulder. “It’s got to be this high.”

Natalie kissed the tips of my fingers and looked at my face and put another coin in. “This is the one,” she said, rubbing her hands. And she was right: suddenly all the lights started blinking at once, and the machine started singing a kind of psycho song. People from the next stool over and the next stool over after that stood up and came to see what was going on. “Twenty bucks says she just won the grand prize,” said a man in golf shorts.

“You’re on,” said a woman next to him. She whipped out her wallet and then started juggling it back and forth.

“I got four cherries,” Natalie sang, and a single, big, fat, golden coin rolled into the dispensing tray. She picked it up with both her hands and kissed it and then asked, “What did I win?”

Which is how we got the tomato plant.

Natalie had called all our neighbors, our friends, and the front desk receptionist by the time we got to the cash-in counter. We were still examining the coin when a man in a white suit walked over, slapped me on the back and said, “Sir, you star, you MVP, you’ve struck gold, you champ; congratulations, sir!” Behind him was another man with a curl of earpiece wire running along his neck, and sunglasses, which struck me as funny — I couldn’t remember the last time I’d seen sunglasses.

I told him I hadn’t done anything. I pointed to Natalie. The man in the suit introduced himself as the floor manager and spoke into a walkie-talkie; after a few minutes some lugs with a cart wheeled over the tomato plant.

It was just a thin stalk with a few scraggly leaves moving shyly upwards, dwarfed by the cart itself. There was a real crowd by then. Natalie moved toward the plant, but the floor manager got to it first, picked it up and handed it to her while everyone clapped. One girl started to cry, in a hiccupping, cheerful way, fanning herself with a scorecard.

“There’s nothing that makes me happier,” the guy in the suit said, “than seeing our residents win.”

Afterward, he escorted us upstairs, chatting happily about how we deserved everything we got. At the door to our home he had his assistant take pictures of the three of us, everybody giving each other firm, friendly handshakes. He wished us luck, and left us alone.

Every day for the next two weeks, friends and strangers would show up, knock on our door, and ask to see the tomato plant. Natalie was keeping it wrapped up in a blanket between two of the candy jars on the counter of the kitchenette, where it would get lots of sun. We all would stand in front of it, eating marshmallows, crammed in the tiny kitchen watching it, popping the marshmallows into our mouths one by one, like at any moment it might wake up and talk to us.

“I can’t remember the last time I saw a plant,” Natalie said quietly on the first afternoon. “A real plant, I mean, in real life.”

“Me neither.”

“When that pipe broke last year,” said our neighbor Beth, “I spent two hours outside.”

“I would chop off all of my fingers,” added her husband thoughtfully, “just to eat a peach.” He sounded sad.

The tomato plant had come wrapped in these glitzy pink beads, and Natalie wouldn’t take them off, even though they spelled out the name of the casino in big tacky script letters: “Les Sables Chanceux,” it read. It meant “The Lucky Sands,” but I thought it sounded like a snobby ranch.

We’d been living in the southern section, where all the roulette tables were, for about four years by then. Like a lot of people, we’d stopped in thinking it was temporary, and then stayed for a little longer, and then just stayed. I don’t even remember where we’d been headed before we stopped. I want to say Utah, maybe — I think Natalie had found a postcard with a picture of Utah on it, and in the picture there was a gigantic lake. But I guess the both of us knew that Utah wasn’t going to be better than anywhere else. No lake, only the same sand, shaping itself into the wind. We’d made it to Les Sables, which I think is somewhere in Kansas, and decided we needed a nice long break.

Natalie and I used to fight a lot, before. Regular marriage fights — I pretend to laugh too often; she criticizes me too much. I wouldn’t say we had issues, but we’d gotten married in our twenties, and after two decades together even our thinnest problems had had time to accumulate into thicker, heavier ones, like stacks of plastic transparencies that eventually stop being transparent. But when the sand started to come up and cover everything and everybody, the fighting sort of died off. We just didn’t have the energy for it anymore. And now, here, in the casino, we’re too busy to think about it: there’s sixty-two floors, live music every night, a mile-long tunnel lit by epileptic laser shows, and twice a year, on the Fourth of July and Christmas, they fill the empty swimming pool up with marshmallow Fluff and we all put on our bathing suits and go wild. The next day everyone goes around real embarrassed.

The last fight I can remember happening at all was in our first casino year: a man had been running from suite to suite, screaming that he’d just reserved the whole floor, that we had to get out. Natalie had stood in the doorway while he threatened her with eviction, and she’d broken his cheekbone with a lamp. Everyone got to stay where they were.

On a banner in the buffet hall, big bubble letters declare Les Sables to be the biggest building in the tri-county area. But I think this seems kind of unfair, because everybody knows it’s the only building in the tri-county area. You don’t really appreciate the place’s size most of the time, but I remember once getting a tour that included the basement, and it was just incredible: the stockpile of dry goods, canned frosting, dehydrated potato, huge sacks of rice, going on and on in every direction without a break, like it was going to keep right on to the edge of the earth.

“When’s it going to make a tomato?” Natalie asked one morning after the visitors had left. She raised her hand to touch it but then let her hand just hover there.

“I’ve got no idea.”

“Maybe it’s a dud.”

“Maybe we’re doing this all wrong.”

Natalie picked up the phone and pushed zero. “Front desk?” she said. “Yes, hello, could you tell me how long it takes a tomato plant to make a tomato?” She listened for a minute, making quiet hums of agreement. Then she hung up, saying, “He didn’t know. But he did say that he’s pretty sure we’re supposed to tie the plant to a stick, so that it can get tall without falling over. He also might come up later to look at it, if that’s okay.”

“A stick?” I said. I looked at the plant. It was just a few inches tall, green with leaves, skinny all over, trembling if we so much as breathed on it. “Where are we supposed to find a stick?”

Every other Sunday, Natalie and I have date night. Date night is when we go to watch a movie in the cinema and we get a SugarShake with two straws. We like seats near the front. We’ve seen most of the movies a few times by now. Natalie’s favorite is a Chinese film — something romantic with long, slow zooms of men beginning to cry. There aren’t any English subtitles but she says she likes the challenge and understands it a little more each time. Certainly, each time she watches it she cries a little harder.

My favorite is when the projectionist blows off his shift and instead they just show the loading screen, which is a looped video of sleepy, distant clouds, floating weightlessly across a warm blue sky. Sometimes Natalie and I stay for the whole two hours, watching the clouds.

A few days after Natalie won the plant, I was getting ready for date night, rinsing off my shaving razor when I noticed that Natalie was still in her pajamas. We did, sometimes, stay in our pajamas all day, but usually not on date night. She was leaning over the counter and talking to the plant in a low voice I couldn’t make out.

“Nat?”

“Shh.”

I stepped into the kitchen. “What are you doing?”

Natalie pressed her lips together and straightened up. She pinched the loose skin at her neck. “I thought it would like the sound of my voice,” still quietly. I felt a twist in my stomach: I could see that she was lonely and that she wouldn’t tell me about her loneliness. This is a terrible thing to know about your wife.

I came and wrapped my arms around her so that I was looking over her head and she was looking into my shoulder. “We’ll be back in a few hours. It’ll be good to get a change of scenery.”

She was completely limp. She felt like a bag of unhappy laundry.

“Try getting dressed,” I suggested. “It always helps me, when I start to feel — to feel claustrophobic. Get dressed like you’re going out somewhere, like anything could happen.” I pushed her gently toward the closet.

That night, it was the clouds again. They moved across the screen with nowhere to get to. It looked like the sky over our old house in Morgantown. Summer, hot, cicadas, moles in the tulip bed. But it isn’t fair to compare the present, movie-screen sky with the old, real sky: the past gets to stay the same, frozen, shining, while the present is always shifting, and maybe getting worse.

I first met Natalie at the Waterfront Place Hotel in Morgantown. I was there on business, marketing medical devices in doctors’ offices. She was there for a convention for people who ran convention centers.

Natalie was at the reception desk, giving a family directions to Ruby Memorial. I’d liked that right away — trying to help people, even though she didn’t have to. She was kind about it, not bossy. She held the door as they left and I noticed that, too. I took out the case which held the equipment I was going to be presenting later that day. When the lost people left, waving their thank yous, it was just us in the lobby. She’d wandered over to see what I was putting together.

“It’s medical equipment.” I held it up as I twisted a microphone into place. “A handheld device for people who’ve lost their voice box.”She picked it carefully from my hands and placed it under her jaw line.

“Electrolarynx,” she said, and her voice was twinned by the machine. I could hear the sound of her smiling.

The plant got taller. In the second week, Natalie said it looked hungry, and she poured some soda pop on it. It lost a leaf or two, but it didn’t die. We went back to spritzing it with tap water. And then one morning, three and a half weeks after Natalie brought it home, we saw it: a tiny green hint of a fruit, the size of a thumbnail.

Natalie rushed out to grab someone’s attention and I stayed, breathing on the plant, seeing its leaves shiver. Go on, I whispered to the plant. You’re doing a really good job. I was thinking about how I was inhaling pure, clean oxygen, like how I’d seen pictures in old textbooks: the cycle of molecules, moving around inside the plant body.

Then Natalie called me from the corridor — she wanted me to come with her to the kitchen of the lobby restaurant, she said, because she wanted to bring up a chef and show him how a real tomato ought to look. “Green,” she shook her head, all the way down in the elevator, “I must have forgot that it ought to look green — and all this time they’ve been feeding us these shit red knock-off tomatoes from tins.”

I followed her down and then through the lobby to the buffet hall.

“The chef,” Natalie said to the hostess, who was standing at the podium by the door, painting her nails. “I need to see the head chef.”

The hostess waved over a server. “She wants to see Allen,” she said. The server disappeared, and a minute later came back with a large bearded man in a splattered apron holding a can opener. He looked warm; physically, I mean — he looked pink.

“I need to show you — ”

His face lit up. “You’re the tomato lady,” he interrupted. He had thick fingers, which he dug under his apron strings.

Natalie straightened.

“I been wanting to let you in a project,” said Allen. “A project I been working on for a time now.”

“Great,” I said quickly, before Natalie could answer, because I wanted to see the kitchen, had always been curious, and I took her hand and followed him.

Allen led us past the buffet table, past the gummy animal salad bar, past the donut brisket and the starch soup tureens and soda pools. He pushed through the swinging doors into a room that led to a series of rooms, with a wide conveyor belt on the side. As we entered, it was trundling out a huge tin labeled POTATO with a picture of a potato on it. With a practiced grace, Allen sprung open the tin and in one smooth movement emptied the gel inside into a nearby pot of steaming water. He moved as though he were unaware that we were still behind him, performing his duties swift and correct. Then he continued, hardly breaking his stride, gesturing for us to follow.

We passed ladles and sacks and piles of brown square parchment packages labeled MOLASSES. In the fifth narrow room, he looked around as though someone may have followed him. Then he moved his hand over a trapdoor in the zinc counter and, in some way we couldn’t see, swung up the latch. He fished in with one meaty paw, biting his tongue, and then pulled out a small plastic jar.

Inside were three brown, dry-looking sticks, curling in on themselves.

“You all know what this is?” He spoke very low. Before waiting for an answer, he unscrewed the top and tilted it towards our noses.

We breathed in. It was cinnamon. The smell came up and with it came Christmas, grandmothers, hot buttered rum, jack-o-lanterns, wassail, Indian summer, yellow leaves, porcelain mugs, knit sweaters, wood fires, pastries steaming on a pan held with an apron wrapped around your hand. We breathed in and breathed in but you can only smell a thing so long, continuously, before it disappears even with you watching, like a good dream you try sleepily to catch.

“Where?” said Natalie breathlessly.

Allen screwed the cap back on, a little jealously, it seemed to me. “Years ago — I won, too. Not a jackpot like you. A smaller thing. The slots: three apples in a row. I used to have more. I saved it for special occasions. But even with my saving, I started to go on see it would run out. Now I haven’t used one in a good while.” He opened the trapdoor, again in a way I couldn’t see, and put it back inside. “I thought maybe — whenever you get ready with that tomato — I got a recipe.” He said recipe like it was a curse word.

“What sort of recipe?” Natalie’s eyes shone.

“Candied tomatoes,” Allen said proudly, and clapped his hands together.

Natalie took my arm. The conveyor belt buzzed and started up again with a chunking sound.

“You’ll let me know when they’re ready — right?” said the chef.

“We should go check on the plant now,” I said, backing towards the other rooms. A white plastic tub moved smoothly past us on the belt.

In our suite, I lay on the kitchen floor while Natalie walked on my back. We’d spent a couple hours at the roulette table before coming back up, and sometimes hunching over the wheel like that made me sore. It seemed like bad luck to go back to the same slot machine as before, so we went to the poker table instead. I was having a lousy few rounds, so I mostly sat and watched Natalie, the other players, the dealer, the window. The dealer’s hands dropped the playing cards and crisply gathered them up again. His nails were bitten back, showing the beds, red and raw.

If you squint real hard, so much that your eyes are closed, the lit-up ceiling of the casino could be sky, and the dark green carpet could be actual ground. But then you always see the window burning — the hot white sky and the dunes that just get bigger and bigger, and whatever they hold, the bones of cattle, skeleton of cacti, probably rusted-out cars, and plus all around you are the beeps and jingles and hot laughter of the people and machines, so it’s hard to pretend, really.

A lady came by with a tray of blue-pink lollipops and I grabbed one, crunched it down, put the white paper stick in my breast pocket. The thing is, in the casino you tend to get into a routine, and it makes time go weird — you’re walking past a bank of video poker screens when you realize a week’s gone by without you really noticing. So at some point around last year I started holding on to leftover bits from meals, just to remind myself: time is passing, time is passing. This is your life. It really is.

Natalie folded. She’d broken even, like she usually did.

We didn’t bring up Allen’s plans about the tomato until we got into the elevator.

“I don’t want it to be candied,” Natalie had said.

“Me neither.”

That was all. The question had hung around the stale air on the way up, fogging up the fluorescent light, bouncing back at us from the mirrored walls: what do you do with a thing you have to ruin to enjoy?

When the doors opened on our floor, the maid was standing by her trolley in front of our room, lifting the keycard from the lanyard around her neck.

“We don’t need service!” Natalie shouted abruptly, startling us all. The maid blinked while we hurried over.

“Privacy, please,” I said quickly, and we’d slammed the door in the maid’s round face.

Now Natalie stepped off my back and sat against the cupboards next to me. I turned my head and felt crumbs sticking to my cheek.

“We have to protect it,” she said.

“Yes.”

“People will come.”

I sat up and sat so that my legs crossed beneath her bent knees. I squeezed her calves, soft and white. Natalie used to be beautiful, tan; she is still beautiful, but a different kind, and pale as the rest of us. It used to strike me as strange to be pale when outside there was always sun, sun, sun, but now that desert out the window is just like the mural of a tropical island painted next to a motel swimming pool: you won’t ever get there, and you have to just use it to enjoy the dingy place you’re really at.

Natalie and I had a trick. We’d been doing it since our first week at Les Sables. We’d walk next to one another down the laser tunnel like totally normal people. Then, as we passed someone, splitting slightly so that we were walking on either side of them, we’d suddenly throw up our hands and scream like goblins and then sprint, fast as we could, to the opposite end of the tunnel. We never actually saw the person’s reaction, but nearly every time we did this, one of us would have to stop before reaching the end of the tunnel, out of breath from hysterical laughing.

It was her idea, and the morning after we met the chef she suggested we give it a go. We’d been strange and distracted all day. She said it’d help us work out nervous energy.

I got dressed and washed, and I put the tomato plant in the hiding place we’d chosen for whenever we went out: in the musty cabinet under the sink. Its leaves brushed the plastic pipes down there. I always felt guilty for leaving it in the dark. We were about to leave when there was a knock on our door. I looked through the peephole. The floor manager, in his white suit, was smiling in the hallway, his face ballooned and alien from the glass’s warp.

“It’s him,” I hissed.

“The chef?”

“The guy in the suit. The one who gave us the plant.”

We both stood there. We didn’t know what to do — here was the man who had given us our favorite thing. We couldn’t just lock out the man who had given us our favorite thing.

I opened the door just as he was lifting his fist to knock. His smile got bigger.

“Our star players! Our MVPs!” He walked in and slapped me on the shoulder, air-kissed Nat. “Our favored guests. Our lucky ducks.”

“Is something wrong?” Nat asked.

His smile went down a notch. Then it was just a regular smile. “Why would anything be wrong?”

Neither of us could come up with an answer to that.

“I was hoping you two could do me a favor.” He sat on the arm of the couch.

“We’d love to help if we can,” said Natalie.

“We have an event this week — an award ceremony — just a little thing we’re putting on. We hoped you would join us, present one of the awards.” He delicately picked one of Nat’s long hairs off the couch arm. “‘Best Janitor,’ ‘Happiest Waiter.’ That sort of thing.”

“Do we have to give a speech?”

“I don’t like speeches,” I added. “I don’t like giving them.”

“No speech.” He threw his hands away from him like he was holding garbage.

“Just presenting. You two — I don’t know if you know this — you’re something of a celebrity couple, now that you’re growing those tomatoes. We thought it’d be fun to include you.”

I didn’t want to. And she didn’t want to. But in front of us stood the man who had given us our prize. We agreed. The next day, a bellhop showed up outside our door with a new jacket and slacks for me, a dress for Natalie in sugary pastels. A card, event details written inside in careful black script; all of this nested in blue tissue paper, paper we kept, because Natalie said it was too pretty to throw out. She had this drawer where she kept beautiful things. She wouldn’t let anyone into it, not even me. She put the tissue inside and closed the drawer.

The ceremony was held in the lounge. Natalie and I and everyone else who was on the giving-end of the award stuff were overdressed: I wore the fine dress jacket, and the janitor wore the janitorial uniform; the waitresses wore jeans. The floor manager in his white suit stood on stage saying Thank you in about a million different ways: We appreciate etc., we couldn’t do it without etc., we are indebted etc., etc. There were bonbons on Styrofoam plates. I ordered daiquiris and then changed it to martinis and then to regular beer. I was embarrassed, didn’t know where to put my hands. Kept them in my lap. I didn’t like being the one with the shiny gold statue in my hands to dole out to winners.

I was picking cotton candy apart on my plate. A slim, balding guy who worked one of the craps tables was seated next to me.

“Who’d you vote for?” I asked him.

A blank look. “We don’t vote.”

“Right. I was only joking.” Some chords of music started up as someone new took the stage. Natalie, on my other side, was whispering and laughing with a maid. She was always better than me at it — at being a person with people. “Are you in the running?”

“I don’t know. I guess.” He looked down at his plate. His fingernails, I noticed, were bitten down — way down, red and raw and painful looking. As I watched, he reached up to his scalp and plucked one his own short hairs; then another, then another. He was doing it absently, a kind of nervous habit that I wondered if I should warn him off.

“Least there’s free food, huh?”

He nodded.

“Got any tips for me for my next go at the craps table?” I tried.

He looked at me and gave a weak smile. “Luck of the draw.”

“How long you been here?”

The dealer shrugged. As I watched, he plucked the cotton candy from his plate, set it aside, and then folded the paper cone carefully and tucked it away in his pocket.

Someone came and tapped us on our shoulders, signaling that we’d take the stage soon. We followed them, weaving around tables, up to the wings of the stage.

“Now, to present the award for ‘Straightest Teeth,’ our celebrity couple — the Tomato Growers!” Mild applause stirred around the room as we stepped on.

The lights were hot and white and made me squint. They were too bright; I couldn’t see the face of the man as he waved us toward the podium. We stepped up and held the plastic gold statue. It looked like a squat hump, an anthill, a buttock — I realized much later that it was supposed to be a sand dune.

“The award goes to — ” I opened the card and Natalie read the name.

“Jeffrey Krugman.”

The man I’d been talking to stood up and came to the stage. People clapped; I shook his hand; he took the statue and turned around and left the stage. We left the stage. The man’s voice boomed on cheerfully. Nat leaned against me; I put my arm around her and pulled hair back from her face. It was time to go home, or to where we lived. We left the dinner, left the beers. The pneumatic door clicked the man’s voice away from us into silence as we walked out. Our steps were quiet in the carpeted hallway. Fluorescent lights showed me the flaws in her makeup. I wanted to kiss her, to apologize for being in this place, unable to leave or taste anything real. I wanted to tell her that I knew the world wasn’t very good, but she was a good thing in it. When we opened the door to our suite, all the lights were shining, the closets open, clothes on the floor. Sand ticked at the window over the sink. Natalie flung open the cabinet doors under the sink. The tomato plant was gone.

We checked the other cabinets, we checked the garbage disposal. Natalie called the front desk, sobbing, and four employees rushed up to help us look. We all spread out in the little hotel suite, scouring it for the plant, for footprints, for a trail of potted soil, something to help us learn who had taken it.

The headwaiter tucked his tie carefully into his shirt and moved around on his hands and knees. The busboy started tipping furniture, in case the tomato plant was hidden under the couch.

“Is this it?” asked the headwaiter. He held up a piece of fake straw that’d fallen from somebody’s hat.

“No,” I said.

“It’s already dead,” Natalie cried. I tried to put my arm around her again, but she shook me off, too upset to be touched. “The chef’s taken it,” she went on. “We all know that he did!”

The waiters looked at each other, and I looked at Natalie. Her nice eye makeup was making dark shapes in the shadows under her eyes where exhaustion usually shows.

“Wasn’t he at the ceremony?”

“I didn’t see him! He was up here!”

She was already moving out the door. She took my hand and pulled me behind her, and all six of us rushed out, crammed back into the mirrored elevator. In the lobby we marched toward the kitchen, past the roulette wheels, past the baccarat table, past the bar with its free shots of corn syrup.

“Can I help — ” began the hostess as we entered, but Nat stormed past her, slamming through the swinging door into the kitchen. The hostess and the rest of the group followed, crying out that we weren’t allowed.

“Wait,” yelled the hostess, but we slammed into the second room.

The chef was there, on the floor. He was hitting his head with the flats of his hands. He said it was gone, it was gone.

Natalie took a knife from the block on the counter. She pointed it at him, jabbing it in the air on every other word: “What did you do? Where’s our tomato gone?”

“Not the tomato, no, no; the cinnamon — the three sticks of cinnamon — the man in the suit took them. He came here. He took them away.”

The chef led us to the floor manager’s office, and Natalie was trying to kick down the door. A crowd had gathered by then. They weren’t cheering, exactly, but people were worried that something bad was going to happen, and then under that worry, excited that something bad might happen. I wasn’t sure whether to help, but finally I joined Natalie and threw my own weight against the door at the same time she did. On our third try, the lock buckled, and the door swung open, banging against the wall.

It took a second to make sense of what I saw, but Natalie was already screaming. The floor manager had an old camping stove, the kind you might take with you on a road trip, and above the roaring flame of the burner was a shallow metal pot. What it held was hardly a sauce — the few small tomatoes were crushed into pulp in the pan, a watery mash of seeds and skin, barely staining the cinnamon sticks. There couldn’t be more than a couple of spoonfuls. It amounted to practically nothing. It smelled incredible.

I slammed the door shut behind me and quickly dragged a filing cabinet in front of it, afraid others would charge in and snatch it away. In the corner of the room, the tomato plant was already decimated. The manager was holding a plastic spoon in the pot, his hand stilled where it had been stirring. I slowly understood that he must have been watching us, all this time, to find the lost spices so he could have the last of every good thing for himself.

“It’s too late,” I heard Natalie say. The knife drooped from her hand and pointed at the floor.

“No, no,” the manager breathed, looking frightened, holding up a hand to keep us back. Someone was pounding their fist on the door, asking if we were okay. “Look — you can have some. We can each have just, just a taste.”

Natalie didn’t say anything. She went over to the plant, which lay on its side, dirt spilling onto the floor. She sat on her heels near the manager and cradled the stem, then looked up, past me, past the casino, out into the net drawing tight around the rest of our lives.

While she crouched there, the manager suddenly snatched up the pot, held it to his lips, and started, ridiculously, to gulp it all, the tiny bit there was, some stray thin juice running a red line from the corner of his mouth. But it was too hot, of course. He choked and yelped, sputtering and dropping the pot which landed on the desk, slopping over and spilling half on the camping stove’s burner so that the flames went out and we could hear the sharp hissing of the gas. The filing cabinet that I’d propped against the door shook as people pounded to be let in.

“Wait!” I yelled, and at the same time, Natalie struck out wildly from the floor with her right arm, slashing at the manager’s legs. She caught him behind the knee and he buckled, went down with a cry. He lay there, clutching his leg and howling like a child.

She stood up over him, heaving, and as I moved toward her, reaching for her shoulder to calm her down, to bring her back to me, the door slammed open, banging the file cabinet into the wall. The two men with sunglasses and radio wires burst in and went straight for Natalie, went for my wife who was crying in anger.

“You can’t,” I said, stumbling as they shoved past me. “That’s ours,” was all I managed.

“I gave it to you,” came the manager’s wobbly voice from the floor beyond the desk. “It belongs to me.”

The security men grabbed Natalie’s arms, pulling them behind her back. She looked, finally, at me, and I can imagine now how I must’ve looked: my hands up, pathetic, tired, knowing already that we were defeated. She closed her eyes and tossed the knife hopelessly toward the camping stove, where it clattered. There was only the tiniest spark.

The gasoline that had been leaking from the stove for a couple minutes caught in a quick roar that made us all jump back, Natalie and the guards hitting the wall just behind them. One of them held onto her arm even as he stumbled and fell, bringing her down suddenly. From where I crouched on the ground, I could see the moment when the back of her neck connected with the jutting metal windowsill. Her head bent back, much too far back, her lovely skull cracking hard on the tempered glass, before she fell to the floor. It only took a second.

Someone was yelling on the other side of the office door. It was very warm. I crawled to where she was. Her eyes were open. I held my hand over her face. I was about to touch her, but when I did, what would I discover? Behind me, papers or files burned on the desk. The manager was moaning, holding his leg. I was about to touch her face. There she was below me on the floor, her eyes open. I was making words but all the sound had drained out of them, and I went to touch her face, and there was ash floating down onto her ears, into her open eyes, and I was about to touch her face but the guard pulled on her arm and her whole body moved bonelessly, a terrible thing to see, her arm flapping whitely against the carpeted floor, like she wasn’t Natalie anymore at all, as the moment resolved cleanly in front of me and revealed that our story would end this way, that my hero finally wound up with nothing.

After Natalie died, I couldn’t play anymore. I couldn’t really move or want things. At some point, I rode the handsome glass elevator up to our suite alone. I finally opened and went through her drawer of beautiful stuff: The tissue paper. A glass ashtray. A poker chip that someone had broken a piece off of, so that it looked a little like Pacman. She’d kept the picture of Utah, like she’d still thought we’d make it there. She’d had all these tiny hopes that she kept bundled in secret, protecting them from everyone, including me. The manager said he wouldn’t press charges. I went back to the electric laser tunnel, but it was just me, walking down a hallway. They were just colored lights. They were just people, going about their business.

In the apartment, I watched out the window. There’s nothing at all out there, so you forget to look: the wind turns up thin tornados of sand, and at night, the glow of casino lights stretch off into the dark, pooling into the valleys, crowding out whatever stars or galaxies might be left up above. The night of the accident, the on-site doctor, once he got there from the baccarat tables, told me her neck had fractured so that she’d been paralyzed, but had been alive — alive for a few minutes — until she suffocated there on the floor. He should not have told me. I have to work hard at unknowing. On the floors below me, electric music from the machines sang and tumbled on.

After a couple of days, I went to the exit door. It’s in the lobby, behind some luggage and empty vending machines. I stopped at the front desk and left my wallet behind; said thanks to no one in particular. The metal pushbar of the exit door was all dusty. There’s a sign above it that says “Emergency Only, Alarm Will Sound,” but no alarm sounds — no one tries to stop you or anything, you just leave.