news

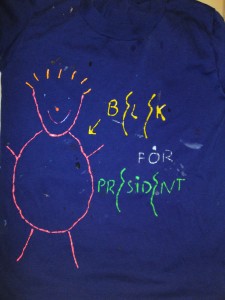

Fallacy in Puffy Paint, c. 1992

Lately I keep thinking about this t-shirt I had when I was nine. Back then, I dreamed of one day owning a whole wardrobe of clothing designed — i.e., puffy-painted — by me. I’d started by making three t-shirts. The first two I wore all the time. One had a big exclamation point on the front and a lime-green question mark on the back. The other read “BELEK FOR PRESIDENT,” and featured a stick-figure illustration of the perfect president America would never have.

But the third t-shirt, the one I’ve been remembering, I was allowed to wear only a few times. This one consisted of a drawing of a cat that took up most of the back of the shirt — I think it also read “Flat Cat” — and then, the cool part, my idea, the cat’s tail went over the shoulder to dangle down, just a bit, on the front. I messed up coloring in that tail, though — I wanted it to have a different-colored tip — and so it didn’t turn out quite how I’d wanted. Most of the tail was a striped lavender, but the very tip was pink, and, because that particular tube of paint had been hard to squeeze out evenly, it was a little misshapen, more swollen than the rest. I couldn’t get it to taper quite like a tail does, either. When my parents first saw it, disappointingly, they’d actually asked me what it was. “You can’t tell?” I’d said, turning around to show them the back of the shirt. In stores, too, people gave my shoulder curious looks. Once a teenage boy gave it a stare, then came back to snicker at it with a friend. That must have been one of the last times I was allowed to wear the shirt in public, before my parents told me (I don’t remember the actual conversation) that probably I shouldn’t wear it out anymore, that the tail on my shoulder actually looked a lot like a penis.

Yes, there was a time when I unknowingly wandered the earth with a puffy-paint penis on my shoulder. But while I like to talk about it for laughs, what I feel when I remember that t-shirt, and what I think I felt at the time, is actually something more like grief. There it was in my drawer: this thing I’d conceived and designed, imagined and realized, and then been asked to put away. As the puffy paint on the other two t-shirts cracked and began to peel away from its fabric, the cat shirt stayed pristine. Sometimes I slept in it — after all, as I’d argued to my parents at first, what did it matter what other people thought it was? What mattered was what it actually was, and as I well knew, it was a cat’s tail. But even wearing the shirt in the privacy and darkness of my own room began to feel vaguely illicit. Because as much as I insisted on the tail-ness of the thing on my shoulder, and as much as I insisted that the only point of view that mattered was my own, it became clear, as time went on, that those ideals had lost some of their truth. Come on. Now that I knew what the tail looked like to other people, was there really a way for it never to look that way to me too?

One lesson here being, of course, that when you are an artist — as when you are a nine-year-old — sometimes you draw cats and people see penises. Or: sometimes you draw penises when you think you’re drawing cats. Or (go away, Freud): you just never know how your work will be read by the rest of the world.

So you take a risk. Right? You wear that t-shirt in public, and in the act of wearing it, of revealing it to whoever will look, you let it go. It’s not all yours anymore, that shirt, even when it’s secured firmly around your torso, even when it sews circles around your arms and your neck. Because sometimes people will stare and laugh, and other times they will stop you and ask, “What does Belek mean?” And even after you tell them, “It’s just a name I made up,” they’ll say, “But what does it mean?” or “How did you think of it?” and it won’t be until almost twenty years later that you’re able to look back and tell whoever will listen that the name was a very prescient cousin of Barack. Duh.

I’ve been remembering and wanting to tell this story, the puffy-paint-penis story, partly to resurrect that cat shirt, to give it some other function (butt of joke?) and thus save it from its pristine, buried-in-drawer fate. And I’ve been wanting to tell it partly out of sorrow for all the unworn t-shirts of the world, all the artistic misfires, the bungled cat’s tails no longer perched on artists’ shoulders. Mostly, though, I want to figure out what that experience taught me about artistic intention. (And intention’s attendant phallusy.) A few years later, when I was a teenager making teenage art stuff, I worked vigilantly to excise conscious decisions from my process, vowing to create everything with eyes closed. Was the t-shirt incident at the core of that conviction?

And if so, am I telling this story to remind my older self not only that risk is necessary, is elemental, to the artist, but also that intentions, those early decisions about meaning, are, finally, beside the point? Yes, perhaps that is the thing I’d like to convince myself of now, again; perhaps that is the reason that this story has been humming so loudly between my ears.

It’s tempting to ask whether, if I were the parent now, I would have allowed the girl to wear the shirt. The question, though, belies the fact that, ever since I learned what else that tail looked like, I have been both parent and child — both knowing and unknowing, complicit and innocent — with respect to my work. Every day, I have to ask, What is this? The answer I give will inevitably be naïve, and the subsequent decision — Can I wear it? Publish? Should I? — will be informed by the knowledge that the thing in question may be perceived as a tail or a penis, or neither. Maybe it’s just some lavender puffy paint squeezed onto a t-shirt that came in a pack of three. I can’t think about it too much; if I really want the wardrobe, I just have to put it on.

— Helen Rubinstein also wrote here about writing offline, and currently has fiction up at Assembly Journal.