essays

Feminism and the Pursuit of Relentless Happiness

Sad Girl Theory in Fleabag, Lemonade, and My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

Over the course of 2014, LA-based artist Audrey Wollen became Instagram-famous and, then Internet-famous for her Sad Girl Theory. The theory was both smart and simple: “Sad Girl Theory is a proposal…that girls’ sadness and self destruction can be re-staged, re-read, re-categorised as an act of political resistance instead of an act of neurosis, narcissism, or neglect.” Wollen stressed that her theory had a “resonance now” thanks to the Pollyanna-ing of modern-day feminism, those urges towards self-love and positivity that chafe if, like so many women, you’re not great at cutting yourself a break:

I feel like girls are being set up: if we don’t feel overjoyed about being a girl, we are failing at our own empowerment, when the voices that are demanding that joy are the same ones participating in our subordination.

Reading the theory felt like exhaling after you’ve been holding your breath without realising you’ve been doing it. Wollen’s battle cry that she wanted “to stand with the girls who are miserable, who don’t love their body, who cry on the bus on the way to work” because “I believe those girls have the power to cause real upheaval, to really change things” was everything after years of Lean In and Sasha Fierce and Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls — which seemed to come with the implicit message that to be a good feminist, a woman must be strong and positive and engaged.

Lean In and Smart Girls seemed to come with the implicit message that to be a good feminist, a woman must be strong and positive and engaged.

Wollen has over 25,000 followers on Instagram, which is a lot, but also feels minimal when examining how far her theory has diffused into the ether of wider pop culture. Because while Wollen dominated 2014 and 2015, giving interviews and expanding on her ideas, 2016 feels like the year her theory began to usher in some sort of sea change in the way women were portrayed.

But maybe this was just because last year was my first year as a full-time Sad Girl, so, of course, I saw Sad Girls everywhere I looked. Normally, I wake up cheerful every gorgeous morning for no obvious reason. My bank account isn’t flush, my career isn’t stellar; for the past few years, my romantic life has been — that most of euphemistic of adjectives — eventful. But all the same, the only period of depression I’ve ever had was triggered by taking an archaic birth control pill for a few months when I was 18. That is, until January rolled round.

The worst of it was, nothing in particular had happened — sure, there had been small disappointments and slights. The abrupt end of a new friendship, stress at work, a particularly ruthless rejection from the person I’d been dating, a not-quite-quarrel with one of the people I’m closest to that still hasn’t healed. But none of the reasons I totted up felt like a justification for feeling so consistently sad last year, sad when I woke up, sad when I went to bed.

None of the reasons I totted up felt like a justification for feeling so consistently sad last year, sad when I woke up, sad when I went to bed.

And reflecting on last year from the perspective of 2017 makes what felt a lot like depression seem even more repulsive. There was the Muslim Ban, the second immigration ban, Trump’s move to reverse Obama-era guidelines on bathroom use for transgender students. Meanwhile, in my home country, Germany, hate crime has rocketed — the Interior Ministry reported this year that nearly 10 attacks per day were made on migrants over the course of 2016. As a cis, white woman living in Europe, my privilege is undeniable. As such, my issue with 2016 felt like T.S. Eliot’s problem with Hamlet, the “objective correlative” — “Hamlet…is dominated by an emotion which is inexpressible, because it is in excess of the facts as they appear.”

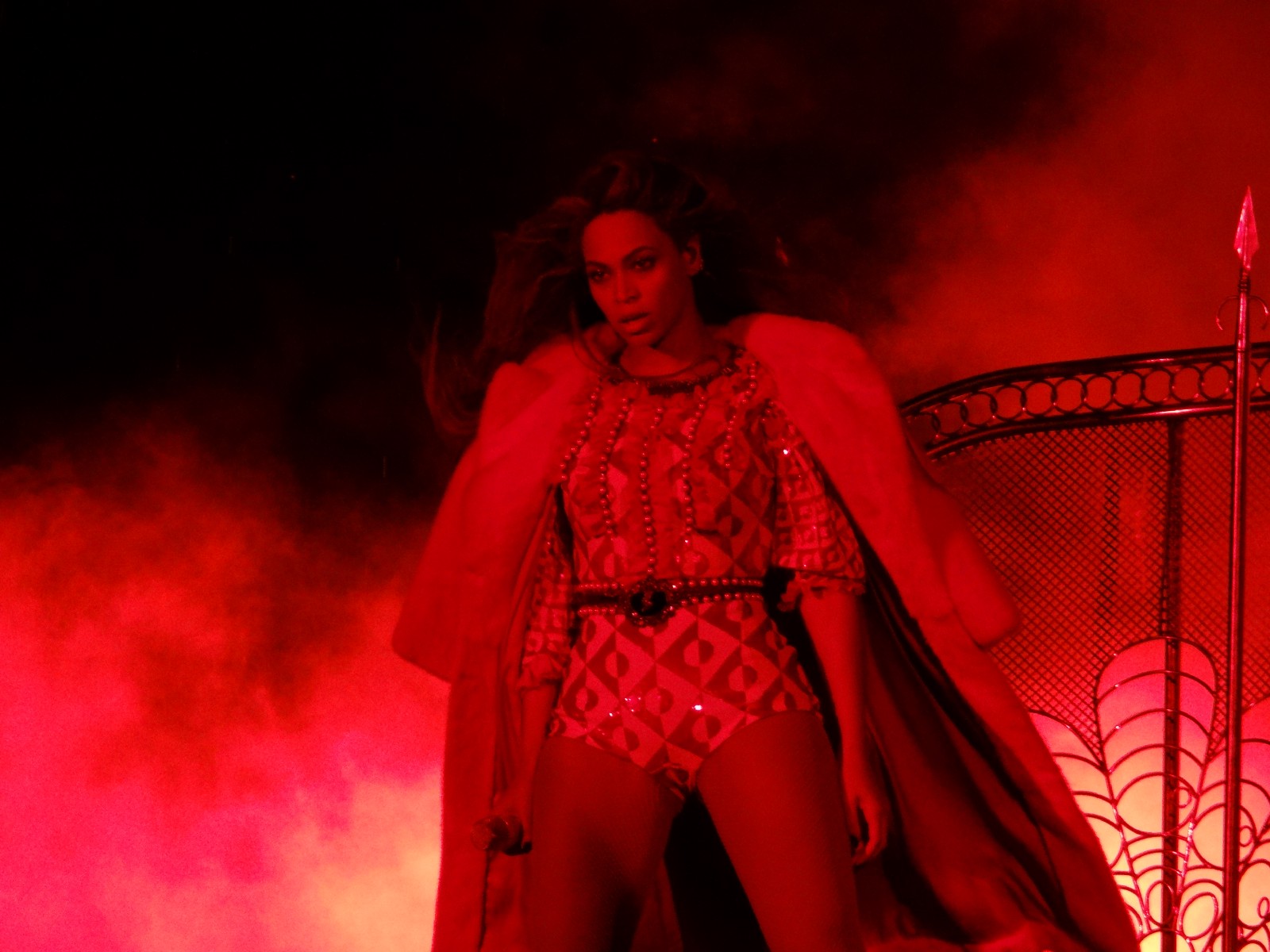

So maybe it was just sad, doughy me, at home stuffing the void with takeout, but it felt like Sad Girl Theory had infiltrated all the biggest moments in pop culture over the past two years. Beyonce’s visual album Lemonade, Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s breakout TV show Fleabag and Rachel Bloom’s My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend each fixated on two things: being sad and being a woman and the connection between both.

Lemonade

Is Lemonade Beyonce’s big reveal of her true alter-ego to the world — Bey coming out as a Sad Girl, not a Sasha Fierce? To some extent. Obviously there’s the flashes of classic Beyonce, the righteous and raging Beyonce we’ve seen before. Less Sad Girl, more strong woman. The baseball bat, the yellow gown, the “if you cheat again, you’ll lose your wife.” Perhaps Beyonce is too much herself to get sucked into the ebb and flow of the zeitgeist. And then there’s that strange, forced fairytale ending, of course. Did it make you wince? “True love brought salvation back into me. With every tear came redemption and my torturer became my remedy.” Less sad, more sadomasochism.

And then there’s that strange, forced fairytale ending, of course. Did it make you wince?

But those weren’t the parts that I remembered long after I finished watching. What stuck with me, despite the women crowded round Beyonce in almost every scene, was the palpable sense of loneliness. In the words of Beyonce (via Warsan Shire) “Ashes to ashes, dust to side chicks.” It was testimony to my mood that I was convinced first time round that the line was “Ashes to ashes, dust to sad chicks.” Because while there were moments of anger and moments of togetherness, I couldn’t see past all those sad chicks. Sad chicks who couldn’t escape themselves in sleep (“She sleeps all day, dreams of you in both worlds”); sad chicks who cried unceasingly in their waking hours (“She cries from Monday to Friday, from Friday to Sunday”); sad chicks who applied lipstick and thought of their mothers and regret (“You must wear it like she wears disappointment on her face”).

If you watch the film again, you might notice that the women in Beyonce’s video do not look at each other a lot. Instead, they are all alone together, gazing with gravity into the camera. While Lemonade appears to reference a whole range of filmmakers and video artists (Terrence Malick and Pipilotti Rist being perhaps the most obvious of these), for me, the work that first came to mind when watching it was the tumblr account, webcamtears.tumblr.com . The website effectively functions as a virtual gallery wall, except the art isn’t paintings but people crying into their webcams and when you hit play, the video loops over and over.

What stuck with me, despite the women crowded round Beyonce in almost every scene, was the palpable sense of loneliness.

Users can heart the videos and the video with the most hearts, by a very long shot, shows a woman with the sort of face that adorns romance novels and pillowy lips who cries at you with unsurpassed gracefulness (punctuated by the occasional delicate sniff, she keeps her face very still and lets tears edge their way down her cheekbones). I couldn’t help but think of her when watching Beyonce, who is also very good at being both pretty and sad all at once, gazing up into the lens with vast saucer eyes.

And maybe watching Lemonade first was what made watching BBC’s great comic hope Fleabag feel so unsettling, because the titular Fleabag (who never gives us her real name) is also big on eye contact with her viewers, but for different reasons: she doesn’t want our pity or our admiration. She’s constantly trying to make the audience complicit in the tragicomedy of being female.

Fleabag

Fleabag isn’t, on the surface, dissimilar to Michael Fassbender’s character of Brandon in Shame. She’s a sex addict who is consumed by self-destructive behavior, who has an uneasy relationship with her sister and who keeps everyone around her at arm’s length (though in Fleabag’s case, via pisstaking, satire and the odd slap at anyone foolhardy enough to attempt a hug). She is not, presumably, intended to be an everywoman.

But Fleabag is constantly courting us, the audience, shooting us conspiratorial looks and cocking one perfectly formed brow at the idiocy of the world around her. The comedy in the show works because its creator has assumed that the sadder aspects about being a girl are universal enough for the female viewer to identify with. Like having enough hang-ups about your flesh prison to sympathize with Fleabag and her sister Claire shooting their hands up when a feminist lecturer instructs a room of women to “raise your hand if you would trade five years of your life for the so-called perfect body” or Claire’s insistence on chiming “I’m fine, everything’s fine” through gritted teeth when it definitely isn’t or the compulsion to reinvent yourself in some minor way (braids!) on getting PMT.

The comedy in the show works because its creator has assumed that the sadder aspects about being a girl are universal enough for the female viewer to identify with.

The predictable comparisons to Girls and Bridget Jones’ Diary have been made, but perhaps the show has struck a chord because it feels so much more radical than both of those works. Fleabag feels like the first character in a female-led comedy whose brokenness seems emblematic, not of her private sadnesses (though the show makes an excellent case for why Fleabag would be so fucked up) but of the broader politics of being a woman.

Sure, there are flashbacks to her own personal tragedy, but these aren’t half as unsettling or effective as her side-eye at the audience while the man she’s having sex with squashes her head down mid-thrust. It’s scary because it’s simultaneously dehumanizing and, if you’ve ever had clumsy sex with someone more set on their own orgasm than on yours, familiar.

This sounds misandrist, and sure, there’s plenty of lousy male characters in the mix. But the show is every bit as critical of its women and their coping mechanisms. Perfectionist Claire’s need for control, whether over her “surprise” birthday party or her calorie intake feels as unhealthy as Fleabag’s retreat from the dark spaces of her brain into the physical, into fucking and jogging.

The jogging — the physical manifestation of the “I’m fine, everything’s fine” refrain of the show — felt familiar to watch. In early summer, when the sadness hadn’t passed and when I couldn’t stop waking up at 4am every morning (google: “anxiety and depression can be associated with early morning awakenings”), I caved to the received feminist wisdom on the topic and embarked on a self-care kick. I went on punishing jogs round the park near my house, sweating in the heat until I’d worked up a headache that pulsed so close to the surface of my skin that it felt as if it was both in my temples and suspended directly outside them. Like Claire, I became obsessive about food, compiling long shopping lists of “good” foods (though my turn-on was endorphins, not a lack of calories) and I ate so much tomatoes and oily fish that summer that now both foods in combination make me throw up. Unlike Fleabag, I tried to face up to things. I went to therapy and tried to think of something to say, how to explain it, fumbled for the words and my therapist told me to “sit with your sadness.” I meditated, or tried to, but my mind bristled and I couldn’t sit with my anything, least of all my sadness. I wasn’t capable of the one thing that might have helped, because that summer I felt too hollowed-out to cry.

Inevitably, one morning at the tail-end of July, I packed my bags and cut my losses.

My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend

Rebecca Bunch is “so happy” in New York, so much so that she can’t stop making statements no truly joyful person has ever made, like “This is definitely what happy feels like.” Coupled with her crushing work schedule, her proximity to her ruthless mother and her grey-hued corporate world, this statement has us rooting for her to outrun her sadness by relocating to West Covina, California. Sure, she’s doing it for a man, her summer camp ex-boyfriend Josh Chan and she confesses as much on multiple occasions — but given that the other aspects of her life seem so much better there, given that she has a work/life balance and great friends and is just two hours (“four hours in traffic”) from the beach, we still tentatively endorse her decision.

But ultimately, while she gets the boy, it doesn’t help. Rebecca eventually muses to her therapist at the end of Season 2:

Well, I moved to West Covina ’cause I thought my problems would be solved by a boy. Now I’m with that boy, and I still have the same problems. So I don’t know, maybe it’s something else. And if he is not the answer, what could it be about? It could be my own issues.

And if he doesn’t help and the great new friends don’t help and the beach proximity doesn’t help, maybe running away doesn’t work. It’s basically the 2017 version of Plath’s depression classic The Bell Jar. Remember Esther Greenwood’s reasoning as to why place doesn’t matter?

This was my litmus test. So it couldn’t have been “real” depression, like Esther Greenwood or like Rebecca Bunch had, because changing up location worked. Unlike both heroines, I wasn’t trapped under the glass bell jar of my doldrums.

For all the pep talks about facing your problems and still being the same person in a different postcode, I never feel more myself than when I’ve moved solo to a new place. I love the adventure of it and the peaceable quality of hardly knowing a soul in a city. So, when that strange hollowness didn’t pass, I set up temporarily in a cheaper, emptier city for the rest of the summer. As I mapped out the contours of the place on a half-broken bike (and fell off again and again until my whole body was patterned with bruises) and swam naked in lakes by myself and smoked cigarettes with my new housemate while perched on our kitchen windowsill, I finally started to feel like myself again. I came back in autumn and my home city looked good to me again and I could sleep the whole night through. I was finally happy, just because.

“Just because.” It’s picturesque. But how much can you ever trust the “just because” of a writer? I can’t help but wonder if the real appeal of the location wasn’t its novelty, but that as a stranger in town, nobody can reasonably expect anything much of you. That whenever I’m in a new place, my unfamiliarity with everyone around me means I can press pause on the people-pleasing I’m so prone to and I can finally do whatever I want to. That moving there, if only for a few months, involved ducking out on the emotional labour of my home city.

Of course, “just because” is doubly duplicitous because it doesn’t acknowledge the privilege involved in feeling better — whether the privilege of being able to work anywhere with a wifi connection or the privilege of being able to move to a heavily white German state with high levels of unemployment and not experience the racism that can come with the territory. Just like Esther Greenwood getting her stay in the fancy mental institution paid for by her literary patron or Rebecca Bunch being able to afford good therapy, I didn’t start feeling better due to some sort of personal integrity or innate character grit, but because I’m privileged.

Of course, “just because” is doubly duplicitous because it doesn’t acknowledge the privilege involved in feeling better.

Normally, in this kind of pop-culture/confessional Frankenstein of an essay, I’d sum up by telling you how I’ve changed and what I’ve learned. But to suggest I learnt something from being endlessly sad would mean deriving some sort of value from something that shouldn’t be capitalized upon and/or glamorizing depression (or its ilk). Let’s leave it at this — it was the year where I couldn’t stand to be told to just exercise more. It was the year I couldn’t always talk to the people closest to me about what I was feeling because I’ve so relentlessly constructed my identity around being happy. It was the year when all the Sad Girls in pop culture made me feel less alone.