Interviews

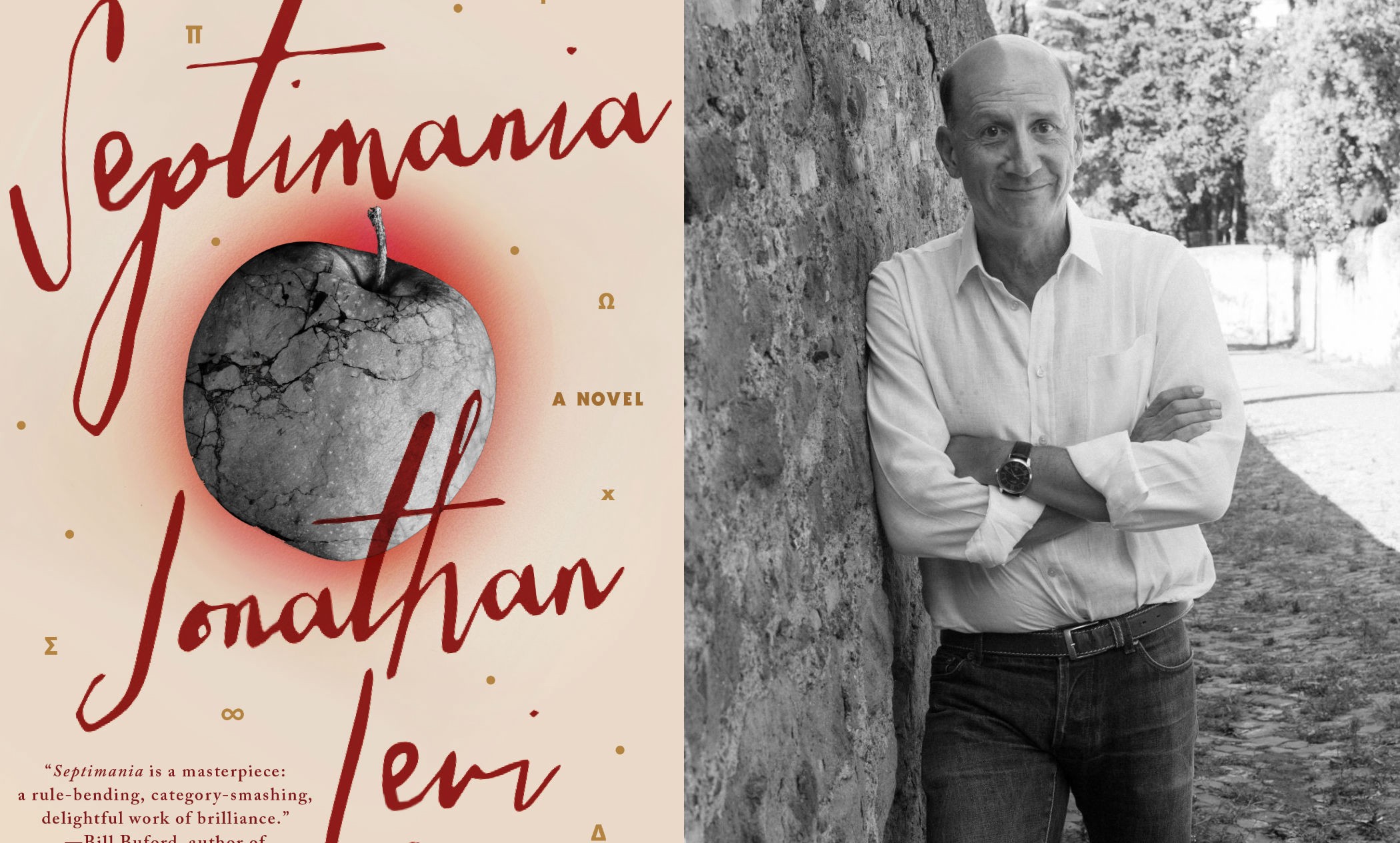

“Fiction Is the Father of Truth”: An Interview with Jonathan Levi, Author of Septimania

Septimania (The Overlook Press, 2016) is a relatively compact yet sprawling novel. In just 336 pages, author Jonathan Levi, a founding editor of Granta magazine, traverses over 1300 years and several countries in the story of organ tuner Malory and his relationship with mathematical genius Louiza, as well as Malory’s connection to Isaac Newton and his own recently discovered lineage within the powerful kingdom of Septimania.

Septimania, which was largely inspired by Levi’s fascination with Rome, is his first published novel in over twenty years, since A Guide for the Perplexed (1992). It was conceived over many years, during which Levi worked a number of high-profile jobs in theater and festival production, and with the New York City Board of Education, among other pursuits.

I met with Levi for a leisurely conversation at a café not far from Columbia University. Though Levi has lived in Rome for several years, he still keeps a home in New York City and travels often for his various projects in theater, music, and journalism. We talked about his many interests and his multi-faceted career, and how it all comes into play in his writing practice and in the themes of Septimania.

Catherine LaSota: You live in Rome now?

Jonathan Levi: Yes, but I still have an apartment on the Upper West Side, and my kids all grew up here. We moved to Rome about 12 years ago for one year, to have the kids see what another culture was like, another language. It was equally foreign to all of us. (My wife) Stephanie and I sort of knew Rome, but we didn’t speak Italian.

CL: Why Rome?

JL: We wanted a big city, because the kids had grown up in New York, and we didn’t want somewhere cold, so we didn’t want Berlin, which would have been exciting.

So we went for one year, and then we came back here for two years, and when I went back again, 12 years ago, that’s when I decided to get back to writing again.

CL: What was it about going to Rome that made you feel that it was time to get back to writing?

JL: Well, it was sort of…I had been ootchity.

CL: Ootchity?

JL: You know, I had been uncomfortable, as though I’d had a marble in some uncomfortable place, because I’d been doing a whole bunch of other things, and I really wanted to get back into writing. I was just finishing up a three-year stint running a performing arts center up at Bard College — I had promised that I would give it three years.

CL: And you gave it exactly three years?

JL: I was counting the last hundred days…

CL: Because you really wanted to write!

JL: I really wanted to write. I went off (to Rome) and had a great year there, and came back here, but I found New York just impossible to write in, because there were so many tempting things.

CL: Tempting how?

JL: In this case, because I had opened this performing arts center — Frank Gehry had designed it — and there was talk about opening a Frank Gehry-designed art center down at Ground Zero, and so I was being wooed for that, which meant that I was wasting a lot of time going down and talking with people.

CL: That sounds exciting!

JL: It is! That’s what I’m saying, that it’s tempting. Because, you know, I have had jobs where there were cars, with drivers…and that’s kind of a nice way to get around New York City.

CL: I hear you.

JL: And you get caught up in that sense of self-importance, and it took over, and it was hard to say no. I remember at one point, after we’d been here for two years — our youngest daughter had done her first two years of high school by that point, our son was off to university — we just sort of turned to each other and said, why not go back? So we went back to Rome. That was 2007, and we’ve been there since. Just stayed and love it.

CL: Much of your novel Septimania takes place in Rome.

JL: People say, “Why did you write about Rome?” Well, I know writers who like to write about other places, but I really prefer doing research in Rome!

CL: Speaking of research, you clearly needed to have a grasp on so much background material to create this novel. I’m curious when you started this project.

JL: There were a couple of points at which I started. One point was probably the mid ’90s. That’s when I had the first idea for this character Malory. It came out of this dinner party I’d been to when I was a student at Cambridge University.

A friend of mine was this wild and wacky historian of science, and his specialty was Isaac Newton, and he grew up as a red diaper baby over there. He had a house that he inherited from his parents, and he painted the lions red, and he had all kinds of people living there, including my girlfriend at the time, and I was at a dinner party there one night. He was doing some work for a BBC series called Omnibus, which was using the guys who wrote the book Holy Blood, Holy Grail. It was a big series on the BBC, and the thrust of it was that they had discovered a secret society in France that was dedicated to rebuilding the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, and bringing back the Moravian Kings. Well, that sounds like a harmless bunch of nutcases, but, the trail of this secret society led to this little strange village in the south of France, in which all kinds of odd things were going on, and a huge treasure, perhaps the treasure of the Cathars (a sort of hermetic sect of Catholics, knights who didn’t marry), had been put down there, and the question was why? The question was, where did things all add up? And they traced it back to the theory that Mary was pregnant with Jesus’s child when she left Palestine, and she wound up in the south of France, where there’s a big cult to Mary, and gave birth, and so that the holy blood — the Sangue Grail, as in Holy Grail, the line of Jesus — continued through the Moravian Kings, and this turned into a French secret society. At one point, Isaac Newton was the president of this secret society. Since this friend, Simon, was an expert on Newtown, he was helping these guys at Omnibus.

So we’re at dinner one night with a bunch of people, drinking and laughing, and a phone call comes through, and Simon goes, “Hello? Oui…oui…oui…oui.” And hangs up the phone. And we say, “What was that?” And he said, somebody called me in French and said, “Stop working on this series, or else.”

CL: Whoa.

JL: So this gave me the idea to start working on a book. I went down to the south of France, and I did some research, and I came back…

CL: Were you writing during this time of research?

JL: Well, I had written one novel, A Guide for the Perplexed, which was published in ’92. I then wrote two more novels, both of them set in South America, and couldn’t get a publisher for them. At that point, I was getting going on this novel, but I was getting offers from other places. There was a project I was offered at the 92nd St Y to produce Dante’s Inferno, and so I figured, this writing thing isn’t maybe working right now — let me put it aside for a bit. So I went off and did this thing for the 92nd St Y, with Dante’s Inferno, and toured the production around the United States, came back, and was offered a great job with the Chancellor of the Board of Education. I did arts and culture for the city, and then that led to the job up at Bard. And that’s why, when you ask why I was “ootchity” to get back to writing…

CL: Well, it’s interesting that you say maybe something else was working better for you than writing during that time, but it sounds like the writing was still gnawing at you.

JL: Oh, very much. Because, you know, when you’re doing these other things, you’re enabling a lot of people. And you’re enabling good people, and nice people. One of my philosophies was, there’s a lot of talented people out there, so work with the nice ones, leave the jerks alone. But at a certain point you want to do your own thing.

Well, meanwhile, this guy Dan Brown came along and ran with this idea from Holy Blood, Holy Grail, and turned it into The Da Vinci Code. So I went, ah, I have to rethink this idea! So that’s what I did. I really restarted (my book) when we returned to Rome in 2007, that’s when I got going on it.

CL: So you returned to Rome in 2007 with the express purpose of working on this novel?

JL: Yes. Now, of course, prior to that, I had done a lot of research. The basic premise, that there was this kingdom of Septimania that was in fact a kingdom of Jews given by Charlemagne, was taken from a book that I saw back in the ’90s in the Columbia University library.

CL: Such a great library. I used to just spend time there.

JL: Isn’t it? And open stack libraries, which are disappearing. A friend of mine did a dissertation years ago on Thomas Pynchon. His thesis was based on the fact that years ago, Pynchon went looking for this one book in the New York Public Library, and shelved next to it, because the books were shelved according to when they came in, was a pamphlet on two other subplots that then became essential to his novel V.

CL: You never know what you’ll happen upon in open stacks libraries. That’s the argument for brick and mortar bookstores, too.

JL: Yeah, you just never know what’s going to hit. So I had done a lot of that, and I had notes and I had thoughts, but it was great to go away (and write). I wrote the first 150 pages of the book in a month in Bellagio.

CL: Did many of those first 150 pages change? This is a very complicated novel.

JL: Yes, huge amounts changed. I think there’s probably three times the amount of material somewhere. I wrote the novel in a couple years, and sent it off. I got a terrific new agent here, and I showed her the novel, and she said, “Jon, it’s a great novel. Ten years ago I could’ve sold it, but not in this literary climate, with literary novels. But if you want to take some notes…”

CL: What year would this have been?

JL: That was maybe 2010. So I took her notes, and two years later I came back to her with a rewrite. There are huge parts that changed, reformatted, whole characters appeared.

CL: Major characters?

JL: Major characters. Antonella had a very small part in the original. The point is, one can always learn. It’s not just a question of being marketable, but I think it’s a better novel because of her notes. There are very few agents you find these days who can do that kind of analysis and push you in the right direction.

CL: Who’s your agent?

JL: Her name’s Ayesha Pande. One of the reasons I went after her is she’s half German and half Indian. I was reviewing fiction for the Los Angeles Times for about five years in the late ’90s, early 2000s, and I just found myself drawn to international fiction much more than American fiction during that time. Part of it that is just a self-sifting process that happens when publishing houses here decide they want to publish a foreign author, because there is so little that is published in translation. I sort of felt that there’s this international consciousness that feels much more like where I want to be.

CL: I was going to ask what you were reading when you were working on your novel — you mention that were interested in international literature.

JL: Well, I was just down in Argentina for the first time. I had been talking to my wife about Borges while we were down there, and she had never read any Borges. I pulled out the beginning of “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” The set up for the story is, he’s having coffee or a drink with his friend Bioy Casares, another Argentinian author, and Bioy Casares mentions a great thinker from Tlön, and Borges says, what’s Tlön? Bioy Casares says it’s mentioned in the Anglo-American Encyclopedia of 1923 or something…so they go look for it, and they can’t find it, but then Bioy Casares gets home and finds his copy (of the encyclopedia), and it’s only in Bioy Casares’s copy that they’ve got an article about Tlön. I hadn’t thought about that until I read it to Stephanie last night, but it’s that kind of thing of trying to remember what’s real and what’s invented. I mean, people sometimes ask me about Septimania, is this really true? And I can’t remember…

CL: The answer is yes, and no.

JL: Well, there’s this Charlemagne expert at the American Academy. At one point I figured, ok, I’ll take her out to lunch and ask her about the things in my book. I asked, do you think this could’ve happened? “No.” What about…? “No.” And…? “No.” And I figured, ok, I’m doing the right thing. But, yeah, (some events in my book were) a little while ago, you know, 1300 years ago…

CL: …and people’s versions of the truth change from person to person and year to year.

JL: Well, there’s another Borges story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” in which he does a fake review where he’s comparing Cervantes’s Don Quixote with a new book Don Quixote written by Frenchman Pierre Menard. He says in Cervantes’s version, it starts off with this epigram: “History, the mother of truth.” And he says in Cervantes’s mouth this is just some quasi-chivalrous nonsense that he picks up all over the place, but Pierre Menard writing after the second World War writes “History, the mother of truth,” and, my god, what a revolutionary concept!

I was in Mexico, teaching, in January, having lunch with a poet down there, a guy in his 70s, and I said to him, “Homero, you know Borges’s ‘History is the mother of truth?’ If history is the mother, who’s the father?” And he said, “Fiction, of course.” So I think that’s the answer.

CL: History is the mother of truth, and fiction is the father.

JL: Fiction is the father of truth, yeah.

CL: I noticed that there is a lot about writing and about books in Septimania. Your character Settimio, a librarian of sorts, takes great stock in books. And your character Louiza talks about how words only started making sense to her when she could visualize them as imaginary numbers. But it’s not just the power of reading and writing that plays a major role in Septimania. Your novel is about so much. It’s also about this intersection of Christianity and Judaism and Islam and physics…

JL: These are all my pet obsessions, and the book gave me a chance to explore them. I suppose this is where rewriting comes through — it gives you a chance to worry them a little bit the way a dog does with a bone, until you finally get the meat off in a certain kind of way.

CL: So, in gnawing the meat off the bone of these obsessions, did you surprise yourself at all? Did you find yourself drawn to certain obsessions more than others? And what were those?

One versus the many. Monomania versus septimania.

JL: Absolutely. One of the obsessions was the question of whether things can be boiled down to “one.” One versus the many. Monomania versus septimania. There’s something so enticing about the idea of one, about finding that kind of unified theory, about finding one love for life and possibly even one god; on the other hand, there’s that huge pull towards complexity, in which you sort of say, not just that it’s fun to play the field, but that the world is such a marvelously intricate and colorful place, that why do you just have bring all the color down to white light? Why can’t it just exist out there?

CL: It’s a huge question!

JL: And that’s what I’m saying, there’s a lot of meat on that bone to play with, and how do you play with it in such a way that it doesn’t become just, you know, either a Frank Zappa song or a dry treatise on something? How do you do it in such a way that it’s going to lead a reader along?

CL: And how do you write about it and not drive yourself insane?

JL: I had hair before I started! (laughs) No, there’s something that’s a lot of fun about writing a novel. It’s like a juggler with a lot of balls in the air. It’s a lot of stuff to keep in your mind, and that’s why things like writing retreats to just get away and have that quiet time where you don’t have to listen to anybody else, and you can just drive yourself insane a little bit for a month at a time, is necessary. Because it’s a lot of stuff to keep going on up there.

When you hear stories about people who have incredible memories, and how they build these memory palaces and put bits of information in different rooms? I think we do that while writing a novel. You put themes into characters and into interactions between characters. If the interaction between Malory and Tibor, let’s say, is one between a character who is committed to “one” (Malory), and a character like Tibor who is committed to “many”– that’s where that theme goes.

CL: Between character interactions.

JL: Between character interactions. Between Malory and Louiza, there are other things, there are things that have to do with language. How do we communicate, how do we make sense of the world?

CL: Let’s talk a bit about your time with the journal Granta. Can you describe briefly what the publishing industry felt like when you started editing Granta, the things that were distinctly of that time? Is it primarily the Internet that makes the publishing industry so different now than when you started Granta?

JL: I’m not sure, because, you know, I’m seeing it still a little bit from a distance. I’m not interacting with it in that kind of way. Part of that is just, as an old guy, it’s just too hard to look at a telephone and read it. I see people reading stuff on the subways, and I just can’t do that. I go on the subway with a book. But, on the other hand, when I’m at home on my computer, to be able to buzz around and get here and there and find things on the internet, more than when I’m searching for something that’s there and digitized, and I can just… I can get it. That’s fantastic.

When we started Granta we were trying to decide whether we should be a non-profit, and we just decided that our personalities were for-profit personalities.

CL: What is a for-profit personality?

JL: It means you want to make money! (laughs) It means you’re in you’re in your early 20s and you want to live better than you’re living now. Plus in those days when we were looking at Granta, we saw these new redone magazines like Esquire and Vanity Fair that were just coming out, and they were selling millions of copies, and we thought, well, if we can just get a small portion of that, we think those are our readers, too.

CL: Vanity Fair and Esquire? You considered those your readers?

JL: Oh, we went after those readers. I mean, when I left Granta in ’87, we were selling 100,000 copies. Selling 100,000 copies.

CL: In stores?

JL: In stores and by subscription. But that was 30 years ago. The world has changed. Back then, it cost nothing to go to the Fillmore East and see Jethro Tull or Emerson, Lake and Palmer, because they made all their money through selling records. Now nobody makes any money through selling records and they make it through concert tickets. Things change. You know?

CL: It’s a different era.

JL: A very different era. I had a cup of coffee with Sigrid Rausing, who owns Granta now, when she bought Granta 15 years ago. I gave her two pieces of advice, because she asked for advice. Number one, I said, just rip up the magazine. We always wanted to do that, and reformat it, and do it a different kind of way. And now I would do that, and I’d have a huge online presence. And the other thing was, I would get an American editor. Granta hadn’t had an American editor since I left in ’87. John Freeman came on as the American editor, and six years later he became Editor-in-Chief, and I think did a fabulous job in giving the thing life again, because it was not in its adolescence anymore.

CL: In addition to your experience being an editor and a theater producer, you also have a background in violin?

JL: Yeah, I still play. I play on the book trailer. I mean, I didn’t want to be a violinist — I wanted to learn violin well enough that I could have fun with it. I still play jazz violin with friends and old bands that I used to play with. The guy that produced the music for the book trailer, Andy Metcalfe, used to play with a band called Squeeze. He and I played together back when I was I was at Cambridge. He was in a group called The Soft Boys, and Robin Hitchcock and the Egyptians. I sat in with all those guys back in the days. Now Andy still has a pick up band, and when I go back to London I play with them — we do Django Reinhardt and that stuff. So, you know, I sort of keep my hand in doing that sort of thing.

CL: And you’ve also written a bunch of libretti, right?

JL: Yeah, and that’s part of, you stop beating your head against one brick wall and you start beating it against another.

CL: Wait — is that how you’re describing doing something creative, as beating your head against a brick wall?

JL: Well, when I realized the books weren’t happening, when I wasn’t getting the novels published, no matter how hard I beat my head against that wall, I went and found these other opportunities.

CL: Have you kept all these fires burning simultaneously? Music, writing, etc.? You said you still play violin.

JL: Yeah, it goes on. This guy Mel Marvin, whose grandfather fought in the Civil War, has had, like, six shows on Broadway — he and I have written two operas together, and one musical, and we’re still trying to get the musical put on. It’s about a really happy musical subject: Hurricane Katrina and the War in Iraq. So you can imagine that’s beating your head against another wall. But we just talked to a producer who’s interested in doing a second production of one of our operas that was premiered in Holland. It’s hard to say no to a lot of these fun distractions.

CL: So when you were working on Septimania, how did you actually get the novel written, amidst all these other interests you were pursuing? Did you have writing days?

JL: I’d like to think that I did. If my wife were sitting here and you asked that question, she’d just start laughing. It’s just (writing) all the time. The nice thing is that, when I finally finished at the Board of Education in 2000, after two years, and they came to me with the tax forms to fill out, I said, what are these? I’d been lucky in that I’d been able to cobble together jobs in certain ways so that I’d never had a nine to five job in my entire life before that. The various projects I’ve done through time, have been projects when I set my own hours, my own time.

CL: And you’re good about compartmentalizing, about setting boundaries?

JL: Well, I like to think that, essentially, I live in a world of serial procrastination, that I avoid one project by working on another one. And eventually I come around to everything I’m doing.

CL: Well, in that way, you get many different projects done, right?

JL: That’s the theory of it. Right now I’m putting to bed a project I do every year. I’m a consultant for a Russian music festival in Lucerne. It’s something I started with a guy in Switzerland five years ago. It’s a lot of fun; it’s great. I learn something every day.

CL: What kind of Russian music?

JL: Russian classical music mostly, but we’ve got Russian gypsy music this year. We’re doing an evening on the poetry of Pushkin and Lermontov, with these two great women, the Russian actress Kseniya Rappoport and a great Latvian accordion player named Ksenija Sidorova. So we’ve got these two Kseniyas with Pushkin and Lermontov…

CL: Hearing you talk about this, about all these different projects and your interests in different areas of the world, it makes sense that there’s such an expansive range to what you’re covering in your novel, too.

JL: Well, everything feeds everything else. That’s the nice thing. To say, therefore, I’ll put a stop to one thing while I’m doing another would be dishonest.

I think part of it is being outside, being away from New York, it’s easy to detach. And Rome is a wonderful, wonderful place to live.

CL: Because of the history, or…?

JL: It’s beautiful. You walk outside, and when you look at all those pre-War buildings, well, that one’s before the Venetian War, that one’s the Ottomans — you know, it’s not just pre-Civil War, it’s 17th century, 16th century, 15th century.

CL: But what is it about being around those buildings that’s so inspiring? Is it being around something that’s been there so long? Is it the physical beauty of buildings that are that old?

JL: I think it’s both. I think that initially it’s just the physical beauty, that’s what hits you for the first couple of years. As you start to get to know it, Italians trust that you’re going to be there, and that it’s worth spending time with you…then you start to get more into it. I’ll give you one example: in Argentina I was visiting a friend whose family goes way back in Italy as well as Argentina, and so he had a friend down there from a famous Italian family, and his wife was French, and she was asking me about Septimania. I was describing to her how it took place in Rome at various points, including 1666 with Bernini, etc. And she turned to her husband and said, “Francesco, when was your Pope?” Their family had a Pope, in 1667 — he was a patron of Bernini and everything.

CL: What. How amazing was that for you?

JL: This is what I’m saying. It’s not just the buildings. Francesco, he’s a really nice guy, he lives on a sailboat most of the year and doesn’t have a lot of money, but his family has a Pope. And not only that, but it’s as if Bernini therefore was the house painter.

CL: Right.

JL: You know, he was the local artist that the family used to hire, “oh yeah, they had him do, uh, those statues up in front of St Peter’s…”

CL: Wow.

JL: So that starts to seep into it, not only at that level, but in the histories of the people that you see. I go running in Rome, and I got into running with a running club because of this waiter Umberto at our local restaurant. He and I go running most Sundays together, and we do these races. And so I knew the history of his family — it’s not like here, where you’re a waiter or a waitress while being an actor or waiting to get on Broadway. It’s four or five generations (of waiters), and I’d hear the stories of what it was like to be a waiter 70 years ago, when his grandfather was a waiter.

CL: That must be interesting because of the identity that carries through generations, much like in your book, where you think Newton is maybe this person, and he’s also that person…

JL: That’s what I’m saying, is that there’s a sense of layering that’s very serious in Rome. And it’s digging through those layers. Not just in seeing how much further down the stream goes, but that underneath each layer, you know, under the layer of this church, there was a Roman temple, and under that there was a Mithraic temple, and under that there were other secret things that went way, way back.

CL: Right. And then all of those secrets create a kind of magic where all these things were piled.

JL: Without a doubt. When we first went to Rome in 2004, we lived on the hill of the Aventino, where I imagine that the real Septimania actually is — it doesn’t take much imagination when you’re up there to think that that’s where it is. In my book, there is a picture of a door in the back of the Pantheon, but up on the Aventino there are a lot of doors like this, locked up doorways in the middle of the hill, and you don’t know what they go to, but at some point people went through them, and they had lives like you and me, and they got pregnant and they had children, and they beat their heads against brick walls.

CL: I love what you said about all these different themes you’re working on, working out different ideas between different characters. It makes me think, well, here’s something that fiction can do that other writing forms can’t do. Like, you could write this story as nonfiction, but you have the unique opportunity to explore these different themes via character interactions in fiction.

JL: That’s absolutely true. Because you’ve got the freedom to push your characters in certain kinds of ways. You know, I think that writers who say they listen to their characters and let their characters lead them…I’m not sure, I don’t really know what that means, unless they’re downright crazy. But I think what they’re saying is that they’ve sort of melded enough with their characters, that when they want them to go a certain way, they know enough of their characters to know how to do that, and how that character would talk were that character to do it, in a very specific way.

I think that’s one of the things, that when you go back and you’re rewriting, you sort of say, eh, you know, I don’t think this quite works, I don’t think she would’ve done this.

CL: But your characters are still a piece of your imagination, and not a physical person out in the world whom you’re following.

JL: That’s right.

CL: So now that you’ve banged your head against the wall with so many different other projects, and you’ve published a second novel, are you going to keep writing?

JL: Oh, yeah.

CL: Are you working on something currently?

JL: Yeah, in the sense that I was working on something pretty hard until January, which is when we left Rome. I’ve been doing a bunch of teaching in Mexico and Colombia, and I was here, doing some stuff for this (the Septimania release). And we were just in Argentina, so it’s one of those things, when I get back to Rome in May, then I get back to it.

CL: Rome is your writing place.

JL: Without a doubt. I’ll get the thing finished by November. The new novel will be finished by November.

CL: How long have you been working on that one now?

JL: Well, again, it’s something I had an idea for about three or four years ago, and a lot of it takes place in Russia. I got a fellowship from a Russian organization to go and do research in St Petersburg, and…well, you can see that I’m a big fan of the idea that writing pulls all of these things together, or it can. The torture is doing it in such a way that you can communicate that to other people (and not just yourself the whole time)!

CL: There’s music in your novel Septimania, and there’s theater in your novel — all of your interests are in there.

JL: Yeah. But I never thought, I want to pull all these threads together, and that’s why I’m writing a novel. This is how I live. And these things are there. The challenge is, how do you communicate them to people who don’t know mathematics, who don’t know theater, in a way that doesn’t feel didactic or in a way that makes it feel like you’re making them feel stupid.

CL: Did you share the work along the way with other people?

JL: Mostly with my wife, who is very good and straightforward and couldn’t possibly lie to me if she wanted to, which is exactly want you don’t want at times, but really want you need. I also showed it to my parents. My father is a philosopher of science, and since there is some science in there I was curious (what he thought). And I think — I don’t know whether you feel like this with your own history, but — while your parents are alive, you still have a good bit of that super ego in which you want to prove (something) to them. I mean, my father wanted me to be a physicist. And…

CL: Here, I wrote about physics, read this!

JL: Yeah, exactly, (to show) that writing can be just as intellectually challenging and demanding as physics. But it was actually very helpful to get their perspectives, because I knew they would understand. My mother has an MA in English, and I knew that they would get it. The question was, where would their eyes glaze over, where would they put it down because they’d had enough? And that was very helpful as well. But I think ultimately, the best editor, the best reader I had, was my agent, and I was just very fortunate to find an agent — her background was at Farrar Straus as an editor — who is just terrific, because it’s not just a question of seeing what’s right or wrong, but saying it to the writer in a way that they’re going to get it, and make it better.

CL: A good editor makes a huge difference in any writing capacity, and actually can help you see what you’re doing sometimes, right?

JL: Yeah, exactly. Or at least can put you in a place where you may be more likely to see that.

CL: Right.

JL: I remember one time with A Guide for the Perplexed, that I had written one chapter towards the end that I thought was going to revolutionize English letters. I thought, people are going to write dissertations about this chapter…

CL: That’s a good amount of ego for a writer.

JL: I think I was between writing drafts of my Nobel Prize acceptance speech at that point.

As I showed the novel to my wife, and she got to that chapter, she threw it across the room and said, “I don’t like it.” I showed it to my parents, and they said, “I don’t know, Jon, about this one chapter.” Well, my ideal reader was coming back to town. I showed her the book, and I said, “How’d you like the end?” She said, “Oh, the end is wonderful!” I said, “You mean this chapter?” She said, “No, no I didn’t know what you were doing there. But I loved the end!” In any case, I sold the book like that, and when my editor got around to that chapter and doing the line editing, which was done on paper in those days, she got to that and wrote me this one note saying, you know, John, I think you’re missing a big opportunity here to do this. Like one sentence. It was a Friday I got that (note). Monday I had a new chapter for her. Because she said it in the right way. Instead of saying what’s wrong with it, or “I can’t read it,” she said, you’re missing an opportunity to do this.

CL: Giving the right push to an author but also not shutting him down, it’s such a delicate balance…it’s a skill.

JL: Yeah, as they say in Spinal Tap, there’s a fine line between stupidity and genius.

CL: So what are you reading these days?

JL: There are two great books I’ve just finished reading. One is Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth. And I just finished her husband (Álvaro Enrigue)’s recent novel published in English, called Sudden Death, about a tennis match between Caravaggio and the Spanish poet Quevedo, using a ball made out of the hair of Anne Boleyn. Wacky Mexicans.