Craft

Field Notes from a Fulbright Scholar: H.P. Lovecraft’s Québec

On a Fulbright to Montréal, fiction writer Cam Terwilliger will be reporting, expounding, fulminating, and otherwise commenting on his adventures in Canada. While he’s there, he’ll be writing a novel set on the border between the warring colonies of Québec and New York in the year 1757.

Don’t let the Fulbright program know, but I keep getting sidetracked by research that has nothing to do with my project. Mostly, I’m writing a novel set in the mid-1700’s, following a doctor who travels with a band of Iroquois natives through the Adirondacks and up to Montréal. But with so much rich history in the province of Québec, it’s hard not to get swept away by tangents.

My favorite pet project is compiling a list of famous American visitors who came before me. John Wilkes Booth frequented the province and planned to escape here once he killed Abe Lincoln. Willa Cather was inspired to write her Québec-themed novel, Shadows on the Rock, after a stopover of just a few days. And Frederick Law Olmstead, designer of central park, engineered the precipitous landscape of Parc du Mont-Royal, at the center of Montréal. Yet lately I’ve been wondering about someone else, a creepier American sojourner to Québec. Maybe it’s because autumn is here and the shadows are crawling over the old row houses on my street a little earlier every night, but I keep thinking of Québec’s encounter with H.P. Lovecraft, the pulp horror writer from the early 20th century.

Even if you haven’t read Lovecraft you probably know his bizarre handiwork. Famous for stories from the magazine Weird Tales, his work runs the gamut from a familiar Poe-like macabre to what he dubbed “Cosmic Horror,” a genre focused on insanity-inducing God-Monsters from other dimensions. These horrific creatures — such as the “squid-dragon” Cthulhu — hide in the most ancient places on earth, no surprise since Lovecraft himself tended to fixate on cities with a strong sense of history. He loved colonial New England, and the decaying towns around his home in Providence often furnished the setting for his stories. Given these predilections, Lovecraft’s pilgrimage to the mecca of North American antiquity, Québec City, was inevitable. A walled settlement dating to 1608, the town was a perfect match for a man who fetishized the past. Stonework. Cathedrals. Sweeping views of the Saint Lawrence valley from atop a cliff-lined plateau. For Lovecraft, the place was nothing less than high-octane narcotic.

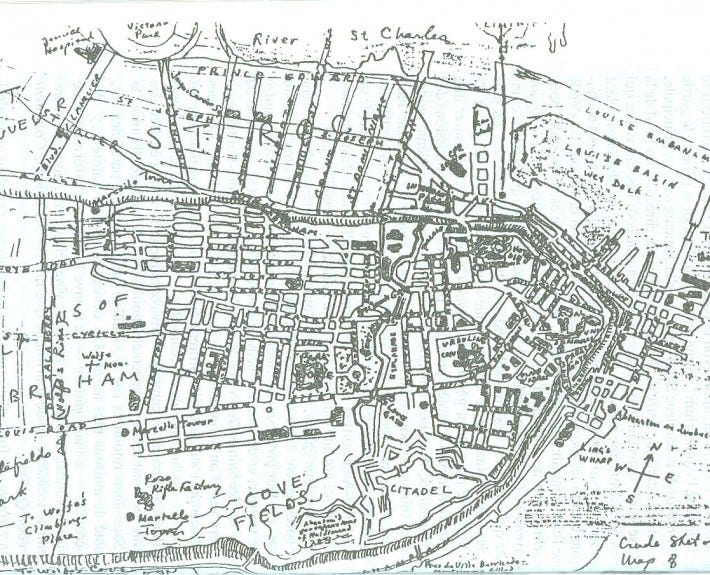

Lovecraft’s three visits to Québec City actually inspired his longest published work, “A Description of the Town of Quebeck in New France, Lately Added to His Britannick Majesty’s Dominions.” It’s a 130 page travel essay about a city overflowing with “the beauty inherent in all ancient and wonder-making things.”

In short, this essay is as weird as Lovecraft himself.

The first half is an amateur history of New France, narrated in a bombastic style that unabashedly flings out baseless Anglo-Saxon value judgments. For example, Lovecraft repeatedly condemns the province as “priest ridden,” and when describing the exploits of Samuel de Champlain, he remarks “’tis a pity he could not have been an Englishman and a Protestant.” Still, despite these laughable barbs, the underlying tone of Lovecraft’s work is swooning, a fact that grows obvious in the second half of the essay: a guidebook for Americans visiting Québec.

In hyperventilating prose, Lovecraft’s guide describes every block of the city in fastidious detail — every cottage, every row house, every terrace, every silver church spire, every “dog drawn cart used to deliver milk.” (Uh… yeah. Dog drawn carts.). Lovecraft’s description is nearly photographic and his obsession with the visual is only underscored by the fact that he constantly recommends certain neighborhoods purely for their “vistas.” Lovecraft extols one such vista in the lower town for being particularly spooky, a crumbling neighborhood overshadowed by Québec’s Citadel, creating a “malign and terrifying aspect” that leads Lovecraft to believe it must be haunted by the ghosts of fallen soldiers.

Reading all this is fun for a while. I can get down with petticoats and stone fortifications more than most. Still, by the end, even I felt exhausted. After Lovecraft’s lengthy “General Orientation Tour,” he then describes 12 more “Pedestrian Expeditions” in similarly exhaustive detail. It all starts to feel like a Lonely Planet where the writer intends to take every step of the way with you, forcing you to ruminate on the provenance of every brick in the city.

Yet Lovecraft’s obsession with antiquity runs even deeper than this. Not only was he obsessed with witnessing old places, he wanted to literally return to the past. As he writes in many of his letters,

Lovecraft felt an intense displacement in the contemporary world

. In one of these, he writes:

I think I am probably the only living person to whom the ancient 18th century idiom is actually a prose & poetic mother-tongue. . . . I would actually feel more at home in a silver-button’d coat, velvet small-cloaths, [and a] three-corner’d hat. . . . I’ve always had [the] subconscious feeling that everything since the 18th century is unreal and illusory. . . .

As a result, throughout his essay, he insists on archaic spelling (scientifick, phantasy, antient). He also bemoans the American Revolution (or “rebellion” as he calls it), longing to restore the good old days of monarchy — even shouting out “GOD SAVE THE KING” every time he mentions a British military victory. For somebody that was a contemporary of the modernists, Lovecraft was flagrantly — almost subversively — un-modern. I suppose being in Québec, surrounded by the century he yearned for, he must have at last felt some sense of peace. In a way, he’d come home.

A sketch of Québec City, drawn by H.P. Lovecraft

Last summer, I traveled to Québec City to do some preliminary Fulbright research and it’s stunning how much Lovecraft’s 1933 description matches what’s there today. This preservation might have something to do with the old town’s enshrinement as a National Historic Site of Canada in 1948 (and a United Nations World Heritage Site in 1985). Of course, even before this, there was an overwhelming monetary incentive to keep the atmosphere “antient,” since the city only draws tourists because of its historic authenticity. This economic truth is something that would have driven Lovecraft crazy if he paused to think about it. One of the things he hated about the 20th century was its overweening insistence on commerce.

Even in Lovecraft’s essay, it’s clear that the tourism industry had already rooted itself in the city by the 1930’s. He describes places to find the best guides, the best English-speaking hotels, and even a phalanx of old fashioned horse drawn carriages waiting to take foreigners around the city.

For all his swooning about antiquity, it’s hardly as though Lovecraft discovered a civilization in a time capsule.

And so, once I finished his essay, I started to wonder if Québec City was really as antique as Lovecraft asserted, or whether he was simply seeing what he wanted to see (or being sold what he wanted to buy). After all, Québec City was one of Canada’s most industrialized cities in the 1930’s, manufacturing an endless supply of shoes, corsets, furniture, and even boasting a new paper mill. But apparently Lovecraft wasn’t shown these things. Or if he was, he ignored them.

The city’s emphasis on tourism would grow still more intense in the last half of the 20th century, as industrial and financial power moved elsewhere in Canada. An object lesson is the reconstruction of the city’s lower town, the neighborhood at the foot of Québec City’s cliff. Ever since the fur trade collapsed in the mid-1800s, the lower town had been a slum filled with whorehouses, frequented by no one but gamblers, sailors, and lumberjacks. However, in the 1960’s millions were spent to demolish and rebuild the neighborhood, the new version made to resemble its ancient 1700’s self, the same era preserved within the ramparts of the city. Naturally, this reconstruction doesn’t house fur merchants as it once did. Instead it contains a shopping area filled with chic cafes, boutiques, and art galleries. If you didn’t think about it, you might assume the reconstructed buildings were centuries old — like everything else. But no. These buildings were designed explicitly for tourism. They are a sanitization of the city’s true past — the crumpled pages of history smoothed flat.

It’s impossible to deny that the reconstruction is an improvement — even if it destroyed that spooky lower town vista Lovecraft admired. What sane person wouldn’t want cheery visitors over a seedy red-light district? Yet the artist in me wonders how to navigate situations like this.

As a historical novelist, how does one separate authentic history from manufactured history?

I don’t have any satisfying answers. But, unlike Lovecraft, I feel suspicious of everything. I’ve been to enough reenactments, historical tours, and museums to realize the quality of these things varies tremendously. I recall visiting one Seven Years War reenactment in upstate New York where it seemed that the reenactors knew surprisingly little about the conflict — most unable to relate more than a few romantic anecdotes.

Still, like Lovecraft, I can’t help but long for some magic door to the past, a way to experience history as it was. This is one reason I feel primary sources are so important. They are the closest you can get to literally reliving the past. For my project, the most useful by far have been the so-called “captivity narratives” — true tales written by colonists taken captive by natives. These narratives render the past in vivid detail, in the very words of those who lived through it. However, as much as I love them, even captivity narratives can be polluted by commerce. Since they were popular entertainment in their day, the stories are often sensationalized, a disingenuous effort to sell as many copies as possible. It seems there’s no way around it. Money will always bend the truth.

So, though Lovecraft felt everything after the 18th century was “unreal and illusory,” I’m left feeling just the opposite. To me, the past is what is illusory, a pastiche of traces we do our best to understand, a story each generation has to remake from a new vantage point. And even though I eschew the manufactured history of tourist traps, my novel is — in the end — just another manufactured version of the past. Even if I strive for accuracy, it will be shaped by my own perspectives. Even if I am skeptical of sources, it will carry forward the assumptions of those I rely on. No matter what: the full truth of the past is lost. The best we can do is a leap of the imagination.