Lit Mags

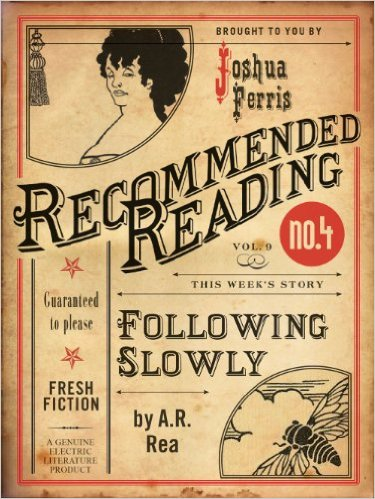

Following Slowly

by A.R. Rea, recommended by Joshua Ferris

EDITOR’S NOTE by Joshua Ferris

I fell in love with A.R. Rea’s stories when I read the first of them several years ago. It concerned an alcoholic mother, a pair of increasingly endangered siblings, and one doomed bird. Since then she has brought to life a Basque shepherd in Colorado, a pair of long-lost sisters selling homemade burritos at the edge of the Navajo reservation, a badly decaying horse, a dog mauling, a dead man stuck at a red light, and a radio-station scavenger hunt that promises a destitute family redemption (and free beer) in the form of a silver keg.

There’s never a false note. There’s never a striving after effect. There’s simply the presentation of a set of facts, a prevailing circumstance that is usually dire, ungoverned, and dangerous. Poverty is a fact of life here. Hunger gnaws at everyone. Case workers and child-care advocates seem always to be waiting in the wings for the slightest gesture. But there is no rescue offered, no easy way out of fate. These are stories about the bottom end of the ninety-nine percent. They’re stories that turn the poor and the neglected and the helpless into flesh and blood. But they do not make them victims. Rea’s characters refuse pity. They defy misery. They find grace where they can.

What they do best is make the reader feel. Here, in “Following Slowly,” I fell deeply in love with Sonny. His predicament is far from anything I know, and yet he is my brother. His mother’s terrible fears for her son are my own. His longing at story’s end is so palpable and heartbreaking that it might as well be mine. I will always remember it and when I recall it I will do so with the same uncontainable emotion. And I will wonder again how Rea makes all of this possible while keeping things so spare, so bare-facts. It’s a marvel. Rea is a marvel. Here’s her latest gift.

Joshua Ferris

Author, The Unnamed

Following Slowly

A.R. Rea

Share article

IT WAS A BRIGHT NIGHT, and the moon was shining on the snow, so it wasn’t hard to find her. He crossed the frozen creek and walked down to a little stand of piñon trees, and the heifer was there, lying on her side. There was frost clinging to her rust-colored fur, and her breath steamed up. She was tired. She scarcely turned her head at the sound of his approach.

He moved toward her with deliberate steps, talking above the sour crunch of the snow. “It’s okay there, girl.”

She was a new heifer, this her first calving. She’d probably been bred by a neighbor’s big bull, which had pushed through the fence that spring. Sonny walked around her and knelt down, lifting her tail, talking softly, the snow cold against his knees. He felt is pocket for lubricant, and rolled up his sleeves.

“It’s okay there, girl,” he said, pushing one hand inside her. The warmth revived his stiff fingers. He felt along the birth canal, closing his eyes to match his mind with the calf’s darkness. The heifer sighed, but didn’t move. He pushed his hand through the viscous warmth, along the outline of the calf’s body and the slick membrane that encased it. The calf was facing the right way, but one of its legs was turned back underneath it, its shoulders were caught on the cervix. It was too big. Sonny remembered having helped his father pull a calf that was similarly positioned — they’d struggled for an hour, and when the calf finally emerged it was stillborn, nothing more than a calf-shaped weight. For three days they tried to coax the cow to her feet with offerings of hay and water, but she could not stand. She wouldn’t even try. Finally, they shot her, and Sonny helped his father hitch her to the truck and drag her to the bone pile. They stood there for a while, his father breathing hard from his growing emphysema, and Sonny shifting from foot to foot, impatient. He didn’t know then that he’d run cattle himself, or that he’d irrigate the same ditches his father walked each afternoon. He thought he’d join the Navy. He wanted to see the world.

He leaned into the heifer now, his fingers working blindly to tear a hole in the amnion sac. There was a weak gush of oil-smelling fluid down his arm. He could feel it now — the slippery ears, the slick snout, the soft bulges of its closed eyes. He found its mouth and pushed two fingers inside. He waited. When he didn’t feel anything, he moved his fingers around, pushing at the calf’s tongue.

“Come on,” he whispered. “Come on, now.”

As he spoke, he felt it — a weak suckling.

He hurried, leaning until he was elbow-deep, pushing hard to turn the calf as the heifer pushed it back. She groaned and her muscles contracted around his arm. “Goddamnit,” he breathed, leaning into her, straining, his face touching her red fur. She swatted her tail in irritation.

When he got the calf turned, he reached around with his other hand to find his rope. He was sweating now, his breath coming out in gusts as he wound a half-hitch around the calf’s hooves. He pulled, but the calf wouldn’t budge. He sat on the ground and planted his boots against the heifer’s rump, pulling and grunting. The heifer was pushing too — he could see her body rocking forward, her neck stretching out. Once, she released a long bellow. Still it wouldn’t come. He’d have to use the truck.

He wiped his hands on his jeans and jogged to it. The night seemed colder in the cab, and he hunched behind the wheel in his bulky flannel coat, trying the engine once, twice, and then easing it across the shallow creek and between two little piñons.

The headlights glinted off the heifer’s eyes, and he saw that she was standing. She lowered her head and watched. The cows usually came to the sound of his truck, gathering around and craning their necks to see if there was any hay in the back, but this time the heifer looked wary. She stood in the darkness, her big sides heaving.

Sonny turned off the headlights. He’d give her a minute to lie back down, and if she didn’t, he’d pull the calf standing. It would be easier if she’d lie back down, so he sat in the dark and waited.

The moon shone yellow through the trees. It was well past midnight, and Sonny was tired. For some time, he’d had trouble sleeping. He fell asleep quickly, exhausted by a day of cows and cold, only to come awake a few hours later in some unexpected place — sitting in the hallway, or standing over the kitchen sink. Sometimes it was hard to know where he was, and he stood awed and dismayed by some common object — a door handle, a sink fixture, the floral pattern of the bathroom wallpaper. One night, his mother had found him on the utility porch, urinating into a stack of neatly folded laundry. My God, she’d said, what is wrong with you? He hadn’t come home for two days, his shame was so great. He’d parked his truck in a field and slept there, curled on the seat, waking now and again to start the engine for heat.

Even now, alone in the truck, the memory made him flush. He reached above the visor for a can of chew. He put a thick pinch behind his upper right cheek and leaned to get a soda can from the floor for a spitter. Then he sat with his hands in his lap, looking out through the windshield at the moon. Sometimes he forgot how good it was to be here, outside, and what it meant to sit alone in such quiet. Sometimes he had to remind himself.

When he turned the headlights on, she was lying down. He put his gloves on and climbed back out into the cold.

He woke after sunrise and the coffee was burned. His mother had left it heating. It didn’t taste too bad with a few spoons of sugar, and he sat at the table sipping and listening to the television going in the other room. The table was strewn with playing cards. His mother must have stayed up waiting for him. She had her back to him now, doing dishes.

“I heard from your brother last night,” she said over the sound of the faucet. “He said Deanette is going to play in a concert at Carnegie Hall.”

“Wow,” he said. “That sounds like a good deal.”

“They’re worried about letting her go to New York by herself, I guess, but Deanette’s awful proud.”

Sonny stirred his coffee. He hadn’t seen his brother’s kids in several years, but he remembered his niece as a glum child with an unruly mop of dark curls. She had a way of looking at people as though they were trying to deceive her, and Sonny had wondered how such a privileged child could feel so wronged. His brother was a well-paid architect, and by the time his children were ten they’d been to ten countries, and did not hesitate to trot out their passports to show this stamp and that. Deannette had sat with her arms crossed while her father showed videos he’d taken in the Swiss Alps and the Galapagos Islands, often videos of her, standing with her arms crossed, looking with endurance at the mist or the mountains or the crashing of the sea. One Christmas, Sonny had taken it upon himself to make her smile. He’d made faces at her until she laughed and made faces of her own. But so many years had passed that he couldn’t imagine what she looked like now. She’d finished grade school and gone into junior high while he was in prison; she’d gotten braces and had her braces removed. She’d grown from a sulky child into a young woman, and in that span of time Sonny had given her very little thought.

It was hard to say what he’d thought about. In the mornings, he worked in the prison bakery, where his mind kept to the bread and the men and the machinery moving around him, and for a brief time in the afternoon he was allowed outside, where he paced back and forth along the fence, because if he didn’t exhaust his legs he’d never get to sleep, and because it seemed a shame to waste his one opportunity to walk doing anything else. He didn’t think — he just walked. And later, in his cell, his mind clung to routine things. He kept his bed straightened, his fingernails clean and clipped.

Still, there were times when he was stacking loaves of bread or trying to keep his eyes on the floor, or when he was in some jostling line of unbathed men, that his former life flooded back and he could see the green of the ranch in summer, the white of snow, the kitchen windows steamed with his mother’s cooking, red cows in the fields with their heads lowered, the trailer in the desert where he lived after high school. He could see the dusty little bars off the highway where he used to go with his friends, sunsets and rainstorms and his own legs carrying him from place to place. He saw himself driving and laughing and sitting on barstools, his arm around a tall, freckled girl. He could smell the interior of his pickup truck and her perfume. These visions were stupefying; they sent him into a kind of paralysis. He accepted no visitors. When his mother came to see him the day after his father’s funeral, Sonny refused to leave his cell. He sat at the end of his cot, blank-faced, unable to move until he knew she was gone. His mind had shrunk to fit the size of his life.

After his release, his brother’s family drove seventeen hours to see him, but Sonny had gone out to tend to the cows, and when he saw their new car parked in the drive, he found himself unable to come inside. He didn’t want to be looked at. He felt they could know it all by looking. If they didn’t cry, as his mother had, they’d be overly cheerful. It exhausted Sonny to think of it. So he walked to the north end of the ranch, irrigating and getting bit by mosquitoes, and he didn’t come back until his brother’s car was gone.

“You must have come in late,” his mother said. “I tried to wait up.”

“That red heifer calved. You should have gone to bed.”

“I know. I drank too much coffee. Was everything all right?”

“I had to pull it, but it was up and nursing by the time I left. A little bull calf.”

“Oh, good.” She dried her hands on a dishtowel and came to stand by the table. Her brown curls were plumped and sprayed in a neat orb around her head, and she wore a pearl necklace over her a high-necked blouse.

“I’m going to do some shopping in town,” she said. “You’d better ride along.”

Her voice had a manufactured cheer to it, as though she’d practiced in her head how it would sound. She began picking the cards up from the table.

“I’ll probably just stay around here,” he said.

“Oh, come. Those cows can survive a morning by themselves.”

“I’ll probably stay.”

He moved some sugar crystals around on the tablecloth with his thumb. He could feel her looking at him, so he put on his heavy flannel shirt and went to the door. His boots were there, still white with snow. He banged them together, reminding himself to get the door re-sealed so the cold air couldn’t leak underneath it. Then he opened the door and stood there, looking out across the yard at the driveway and the frozen tops of the trees beyond. The sky was clear and blue.

“You go ahead,” he said. “I’ll get your truck warmed up.”

And he shuffled out.

He was feeding when he heard his mother’s truck rumbling away. He couldn’t see it from the field, but the engine made a droning sound as it moved away down the county roads, and he listened, thinking of how far sound traveled, how on some windless nights he could hear vehicles traveling many miles away, as far as the road to the dump and the highway into New Mexico.

The cows moved among broken hay bales, and he surveyed them, wishing he’d asked his mother to buy him a new package of razor blades. And something sweet. He’d always had a sweet tooth, and there was nothing he liked more than a piece of cake for breakfast with a glass of milk. Sometimes he liked to pour the milk over the cake and eat it with a spoon. But his mother bought sensible groceries: rice, beans, pork roasts, potatoes. She went to their meat locker and picked up packages of hamburger and steaks. It was forty miles to town, so she brought home enough to last a month. They never had dessert, with the exception of some canned peaches poured into a bowl. But Sonny didn’t complain. He was a grown man who should have had a family of his own, and although he knew his mother relied on him to take care of the ranch and their finances, he didn’t feel at liberty to add to the shopping list. He ate what she ate. He watched what she watched on television. When she urged him to take one of the upstairs bedrooms, he declined. He slept in the basement, on the same twin bed he’d used as a boy, under the same quilted blanket.

Around him, the cows shouldered each other and swung their heads, grabbing mouthfuls of hay and chewing them with slow, circular motions. A few watched Sonny incuriously as he counted them. The red heifer was there, with the young calf at her flank. Its legs were still spindly; its fur was a bright and undulled red. Sonny watched it, thinking how little the world seemed to surprise a newborn. The snow, the sun, the big jostling herd. The calves looked at everything as though they’d expected it.

When he got home, the house was quiet. His mother was still in town, and without her, the place felt empty. Even the clock had ceased ticking. Sometime the week before, it had suddenly quit, and Sonny had taken it down from the wall to find that its batteries had run out. He’d forgotten the thing ran on batteries, it had ticked so reliably, and for so long.

The clock had stopped at 4:15, and the sight of it there on the kitchen table gave him a feeling of dim anxiety. Four o’clock had been count time. “Count!” they called. “La Cuenta!” Every day, inmates up and facing the bars, while guards walked the corridors, counting. Guards in heavy boots, guards with batons. The same guards who told the men to bend over and spread their cheeks, who brought the mail and told jokes and made deals for cigarettes. Their footfalls were slow and deliberate. At the end of each tier, they called out in flat voices to the guards waiting below, guards who marked a sheet to verify that every man was present, every man alive. “The count! La Cuenta!” Every man shuffling to the front of his cell. Men with bare feet. Men with wide stances and dead, contemptuous eyes. Men who raged and snarled until the hair stood up on Sonny’s arms. Men who laughed, slow and easy, as though even this was a minor nuisance in their lives.

He walked through the house and poured a cup of burned coffee, now cold. There were oily patches at the surface and he sipped, hearing himself sip. There was not another sound. He drank the coffee and filled the cup with water from the faucet, then walked across the carpet in his dirty boots and sat down, listening to the quiet.

There had been no quiet in prison. Even as he slept he’d heard clanging doors, sliding locks, shouting and laughter and groaning in the bright night. Keys jangling, guards walking up and down, up and down, boots on concrete and ringing, buzzing, bells. In the quietest part of the night, he heard his cellmate breathing and whispering in the half dark, smelled his musky sweat from the bunk below. “Baby,” he’d say. “This is reality. This ain’t no joke. We’re living in Hell’s Glory. This here is why they call it hard time.”

His laughter was a low, mirthless rumble. He liked to talk, whether Sonny was listening or not, and some nights he spoke to the bottom of Sonny’s mattress like a friend at a sleepover, moved by some imaginary night sky to confide his thoughts and observations. “How’d we end up here, Baby? I still can’t figure that one out.”

He was an older man whose offenses unfolded in the stories he told — the time he robbed a liquor store in Salt Lake, the time he took his son from his ex-wife, the third time he violated parole — until Sonny began to wonder if more than a week had passed in his life in which he hadn’t run afoul of the law. He’d been in another prison before he became Sonny’s cellmate, and would be moved to another prison before Sonny’s time was done. But he didn’t seem to comprehend it. He looked around the cellblock and shook his head in disbelief.

“How’d we end up here, Baby? That’s what I’d like to know.”

Sonny understood how he felt. He’d slept through his own crime. How, he didn’t know. He awoke only afterward, on his back in a dusty field, a confetti of broken glass all around him. There were sirens, too, and he saw them before he heard them, red lights flashing across a sagging black sky. He looked down his body and saw his right leg hanging above him, twisted so that his toe pointed off to the side. The boot he’d been wearing was gone, and his foot was bare, the skin white in the darkness. There was blood on his jeans — a dark patch that spread and grew cold as he lay there. Shadows moved around him, talking shadows. He’d killed someone. Her name was Iona Mindich, and she was fifty-nine years old.

Sonny put his hands flat against his thighs. They trembled sometimes and he had to stuff them in his pockets or put them to a task. Across the room, the blank grey screen of the television miniaturized his reflection. There was work to do, but he couldn’t recall what. It didn’t matter what. He looked at the worn fabric of the couch and remembered lying there as a small boy, watching cartoons, and the strange loneliness he felt when his mother and brother were still asleep and his father had gone out to feed. It was hard to believe he’d ever been small enough to inhabit a single cushion.

He’d tried to imagine Iona Mindich as a child, but he couldn’t. He’d never seen anything of her but a photograph of a frail woman with wiry gray hair and a mouth that looked somehow crumpled. She’d lost her teeth to a childhood ailment, and the face she was making in the photograph was as close as she would get to a smile. For fifteen years she’d worked the graveyard shift at the supermarket bakery in town, and during that time he’d probably eaten dinner rolls she’d put in the oven, though he’d never seen her face. He’d seen it only in the newspaper, her flat gray eyes and mouse-gray curls. What details he knew of her life he’d learned from her sister, a small, pious woman who stood to deliver a convoluted monologue at Sonny’s trial. She spoke of her loss, and of righteousness, and declared with a quavering voice that the Lord hated the hands that shed innocent blood, that they were abomination, and that the name of the wicked would rot.

Baby — that’s what they’d called him in prison. He’d grown a beard, but they’d made him shave it, and there was nothing he could do about the youthfulness of his face, his smooth skin and dark eyes, his eyelashes long enough to be a woman’s. Inmates in the laundry had written it on his socks in big black letters: BABY. He’d been home a week when his mother took it upon herself to launder his sack of rumpled clothes and found them. Sonny found her soaking and scrubbing, crying into the sink.

“What does this mean?” she’d asked. “What did they do to you?”

Sonny had been unable to answer. He’d walked away, wanting to hide his face, mortified that she’d asked him. He could think of nothing worse than his mother imagining him raped, if that was the word for it, and he lay awake that night trying to find a way to reassure her that he was still a man, his father’s son, the same person she’d always known, regardless of what had happened to him. But there was no way to approach it, no way he’d ever in his life speak of it.

So they’d gone on in shared silence. She’d thrown the socks away and replaced them with new white socks, and hadn’t mentioned them again. And yet Sonny still felt the weight of her question. He felt it in her eyes sometimes, and in the quiet that settled over them during the long evenings in front of the television. They sat and watched, but sometimes it felt like neither was really watching it at all.

He should get up, he thought, and shovel a pathway to the shed. But he couldn’t yet move. He sat there, eyes heavy, watching the way the walls loomed. If he stared long enough they seemed to advance toward him, and if he concentrated he could convince them to back away.

Outside, a cow bellowed from a distant field, and a cold wind rustled the naked branches of the chokecherry bush by the door. He sat there for a long time, following his thoughts down dim passageways, following slowly, with resignation, until the door opened and his mother was standing there, a brown bag of groceries in each arm, and he got up to help her.

II.

She died that summer, leaving Sonny alone. He ate poorly, and his laundry piled up in the utility porch. The kitchen developed a layer of grime he was helpless to eradicate. It was two years before he boxed her things and moved out of the basement into one of the upstairs rooms.

Each year he made a profit, if modest, at the sale barn, and put everything into savings. He bought little except food and soap, the occasional pie at the bakery, the odd pair of jeans. He celebrated his mother’s birthday when it arrived, but failed to remember his own unless his brother called for a tongue-tied conversation. He sent generous checks to his niece for her graduation, her wedding, the announcement of her first baby, announcement of the next. He grew accustomed to evenings by himself, simple dinners of meat and frozen vegetables, the radio playing faintly from its place beside the stove. And while his dinners verged half the time on inedible, he made himself eat them — he made himself cook something and put it on a plate and sit down with a napkin and a glass of milk. It would have saddened his mother to see him as he was during that first year of her absence, drinking cold soup from the can, leaning over the sink to eat a forked steak.

In the fall, he cut firewood, and in the winter he burned it. In the spring, he planted alfalfa. At an auction he purchased a little antique tractor and painted it bright red. He didn’t know why he’d bought it, or what to do with it, so he parked it in a corner of the yard. When the paint faded, he touched it up. When grass grew up around the tires, he knelt and tore it away. It was the only gardening he bothered with. The wild roses, which his mother fought so hard to contain, grew unchecked. They spread across the yard, shoulder-high, a labyrinth of perfumed brambles and bees.

When summer was gone, he divided the heifers from their calves, and for a week his ears rang with the sound of their bawling. Day and night they called to each other, the calves in the corral growing more desperate as their mothers drifted further and further afield. Their babel reassured Sonny enough that he could sleep. It was their silence that woke him — a sudden hush that came over the ranch when the calves wore out. It was then that the shadow of a flying owl or a breeze rustling across the hillside could bring them to their feet, wide-eyed in communal panic, to slam against the bars of the corral like a great wave and flow over the downed fence and across the fields to the last place they saw their mothers, to the memory of milk, and he’d have to begin all over again.

During this time, a neighbor began to visit, an old rancher from the property to the north. Sonny had known him since boyhood, when he’d been conscripted to help wrestle calves or hay bales for a few dollars a day. It had been hard work for a boy of Sonny’s size, and when it was finished, he’d follow Bob Bitts to his rattletrap house, where the old man assembled plain meat sandwiches. There was nowhere to sit. The house was choked with furniture, but all was occupied by dusty boxes, these filled with oily tools and car parts and who knew what else. Magazines were stacked and strewn about, and Sonny caught glimpses of glossy women cupping enormous, pale breasts.

If Bitts had seemed an old man then, now he seemed ancient. His thick sideburns had gone white along with his hair. He’d grown squat and bandy-legged, Leprechaunish. His rounded belly pushed his jeans down so that he was continually pulling them up. Each week, he arrived in his battered truck, bearing what news he’d overheard at the post office and a bottle of whiskey. Though Sonny resisted the whiskey at first, he found that it warmed and calmed him. It became a small, but reliable pleasure.

Sometimes, in fact, Bitts stayed late into the night, and the two of them drank until the living room swam around them. Both were accustomed to solitude, but with the right amount of whiskey they found themselves in long discussions about things like evolution, the economy, outer space. Some nights, Sonny found himself giving philosophical orations that he didn’t entirely believe or understand, but felt powerless to stop. Even when he saw the old man’s head falling forward and his eyes drooping shut, still he talked, words streaming from him of their own volition.

Other times, it was the old man who held forth, telling such long, repetitive stories that Sonny had to shake himself awake. And some nights, neither had a thing to say, and they simply sat together like mutes.

One evening, Bitts arrived carrying a letter. He didn’t mention it, but poured himself a glass of whiskey and sat with the envelope between his thick, dry fingers. Sonny looked at it, recalling that Bitts sometimes prevailed upon neighbors to help him with his mail. He claimed far-sightedness, but everyone knew he was illiterate, that he could scarcely decode his own name on the outside of the envelope, let alone write it. According to Sonny’s mother, he’d known how to read once but had forgotten it over the years, as some people learn and forget foreign tongues. Many times she had written the old man’s checks while he hovered behind her, pretending to police every stroke of the pen.

“What’ve you got there?” Sonny asked.

Bitts rearranged himself in his seat. “There’s a piece of mail here I need to read. But my eyes are just about shot, see.”

He passed the envelope over the coffee table with some reluctance.

“It’s from my daughter,” he said. “I bet you didn’t even know I had a daughter, did you?

“I might have known, but I’d forgot.”

“Well, I damned near forgot, myself,” Bitts said. “I haven’t seen her since she was small. She lives in California. At least she used to. I can’t see, is my trouble. I’ve pored over it a hundred times, and I just can’t make the words out. I don’t know why people have to write so damned small!”

Sonny looked at the envelope.

“You just want me to read it aloud?”

Bitts nodded. “If you would.”

“What if it says something you don’t want me to know about?”

Bitts laughed. “Like I said, I haven’t heard from her in years. If there’s something in there you don’t want to know about, I guess I don’t want to know about it either.”

Bitts’s smile faded. Sonny opened the envelope. Inside there was a single page of jagged blue handwriting. It was not small, as Bitts had said, but in fact large and loopy, and it switched from print to cursive and back to print.

“Looks like you’ve got the same trouble as me,” Bitts said. “I just can’t see well enough to make it out.”

“I can see it all right.” Sonny turned slightly to find the lamplight. It felt strange to read a letter written to someone else, a letter written by a woman, and he was reluctant to interject himself between the words on the page and Bitts’s evident eagerness. But after a moment, he cleared his throat.

“Dear Daddy. I know it has been a long time since I’ve written to you — years and years. But I hope this letter finds you happy and healthy. For all I know you don’t even live at the ranch anymore, I just can’t imagine you anywhere else. And Mom said I could probably find you there.”

Sonny paused, conscious of the monotone sound of his voice, the way he stumbled over the handwriting, which seemed to get worse as the letter went along. He glanced at Bitts, who was leaning forward with his elbows on his knees, frowning at carpet.

“Maybe you didn’t know I got married,” Sonny continued. “But I did, and then I got divorced. Life is strange, and that’s why I’m writing. I’m coming to see you. I’m looking for a change of scenery, and if you want to know the truth, I want to get to know my Dad.”

Here, she’d drawn a smiley face — two dots with a lazy U-shape underneath it.

“Nothing is decided yet, but I think I might have found a place not too far from you. I hope to see you in a few short weeks. Your daughter, Betty.”

Sonny lowered the letter and looked at Bitts, who was staring out over the cluttered coffee table. His face — usually a deep, weathered red — had paled. He raised his shaggy eyebrows and let out a breath that puffed his cheeks. Then he took off his hat and smoothed down his white hair.

“Well, I’ll be damned.”

Carefully, Sonny folded the letter back into the envelope.

“I’m going to have to find somebody to clean the house,” Bitts said. “A professional, or a whole team of them. Somebody who knows their way around a vacuum cleaner. Can you tell what the date is? When it was sent?”

Sonny looked at the little printed circle in the corner of the envelope.

“Looks like February twenty-seventh.”

“That’s two goddamned weeks!”

“Just about.”

“Well, I’ll be damned.”

She arrived within a week, and only a short time later moved into a doublewide by the side of the highway. On Sundays, she fried chicken, and Bitts showered and parted his hair before going to her place for dinner. He went around town as proud and moony as a man in love. “She’s the only one in the family has any brains,” he told Sonny. “Her mother raised her in California, so she’s got more culture than any of us here.”

But people formed their own impressions, owing in part to an appearance she made at the mini-mart, braless, for some milk. She asked for a fancy cigarette that the store didn’t carry, and she had a tattoo of a skull on her upper arm that she made no effort to conceal.

Her name was Elizabeth Bitts D’Amico, but she introduced herself as Betty Bitts. When Sonny suggested that she must be dismayed by the backwardness of the town, she laughed out loud.

“I guess you’ve never been to Barstow.”

He hadn’t, though he didn’t say so. He was hammering a cedar plank under the eaves of her new doublewide, trying to cover a hole where some starlings had nested. Bitts had asked him to do it, as he didn’t trust himself on a ladder and didn’t want his Betty doing any rough work.

Betty stood just below him, on the second step of the porch, shading her eyes from the sun. It made him self-conscious to have her watching him, and he focused on not dropping the hammer on her bare feet. She wore a long, shapeless dress — Sonny didn’t know if it was a housedress or what — and from where he stood, her toes were visible, small and polished pink.

When he finished, she invited him in. It was a hot afternoon and she had a pitcher of sun tea sitting there on the table. He could see it from the porch.

“I’d better not.”

“Oh come on. It’s bad enough my Dad sent you up here. At least sit down a minute.”

“I appreciate the offer,” he said, wiping the sweat from his hairline. “But I’d better get home.”

At home, he took off his overalls and hung them over a chair. He retrieved a chocolate bar from the box in the pantry and ate it while he watched the news. The channel was out of Albuquerque, where there were fires and floods and gangs, crimes so unspeakable that Sonny turned the television off. He couldn’t stand the newswoman’s relish, her lipsticked pronunciation of horrors she’d never herself have to see.

He lay in bed, not asleep, but not awake either. He tried, as he did every night, to prioritize his work for the following day. But his thoughts strayed to Betty. She caused a rising thrill in his gut, a feeling he tried to deny and ignore. He reminded himself that he was an old bachelor, content to go days without speaking a word to anyone, and that he’d darkened his teeth with chew. He’d gained twenty pounds in the last few years, and his jeans hadn’t always kept up. He lived in pair of brown coveralls except when he went into town, and then he wore one of his father’s old dress shirts. He didn’t even know what people did to polish themselves up. He had no business looking at women or thinking about their feet.

But here in the privacy of his bed, he indulged in the memory of her, and a warm feeling that he might see her again. Despite himself, he began devising excuses. He’d double-check his work on the eaves. He’d knock down some of the weeds around her place — the sunflowers were approaching waist-high. He’d bring her some firewood, though winter was months away.

It kept him up late. He lay awake, his hands clasped over his chest.

It was the sunflowers he settled on finally. He put a scythe and a shovel in the back of his truck and drove up the highway. It was early afternoon. He hesitated before turning down her drive, worried that she might not be home. Or that she was. The realization made him flush with panic — her car was parked right in front of the house, a well-used green sedan.

He drove slowly, hands shifting on the steering wheel. What if she had a man there with her. What if she was in the middle of a bath, or doing something private, and felt intruded upon. What if she was in there doing drugs — he didn’t really know her, after all, and what kind of woman would wear a tattoo of a skull on her arm? Tattoos were reminiscent of places and things a woman shouldn’t know about, of fat men sweating as they etched them, of brown men marking themselves as part of this gang or another, of men whose every movement was a threat. He shouldn’t have come. He should have brought Bitts with him. He should have waited for some kind of invitation.

But it was too late. He was idling there, in view of the doublewide, and she was looking right at him. She had one hand on her hip and the other holding a garden hose, with which she was filling a bright blue kiddie pool. There was a toddler in it, a pale-skinned blonde boy splashing. There was another kid on the porch. The screen door swung open and another peered out, a chubby-faced girl wearing a shiny dress and a pair of pink wings.

Betty smiled. She lifted her hand in greeting.

Sonny got out. Everyone watched him. He ambled over to the far side of the kiddie pool. Behind him, he could hear the truck clanking faintly as the engine cooled.

“Hey Sonny.” She was shading her eyes from the sun, and her hair looked matted from sleep.

“I was just driving by,” he said. “I thought I’d stop and offer to knock down some of these weeds.” The boy in the pool turned to look up at him, his face scrunched against the glare of the sun. He had small square teeth and wore small white briefs.

“You mean the sunflowers? I sort of like them.” Then she hollered over her shoulder: “Lacey, turn off the hose!”

The little winged girl ran noiselessly down the steps and around the side of the trailer.

Betty nodded toward the boy in the pool. “This is Stephen,” she said. “That’s Tucker and Lacey. I’ve got two more back in California, my older girls. I bet you didn’t know I’d popped out so many.”

“I didn’t know either way.”

“They’re with their Dad a lot of the time. But I’ve got them the rest of the summer.” She looked around at the dry ground and the white side of the doublewide. “Now that I’m settled, I hope I can keep them for good.”

The older boy was sitting on the porch steps, watching Sonny through two of the rails. The girl ran to Betty’s side and took a handful of her shirt, then peered around to look at Sonny’s face. Sonny thought the urgency of his heartbeat would choke him, and that his distress would be visible to all. But the boy in the pool was busy splashing, and Betty was looking down at him, looking pleased.

“I guess they miss the ocean,” Sonny said.

Betty gave a slight smile.

“I’ve never seen it,” he continued. “But they say it’s something everybody ought to see.”

“We lived in the desert.”

“Oh,” Sonny said.

He looked down at the little boy in the pool and after a moment he spoke again. “What you need is a hot tub. Something they could swim in year round.”

Betty laughed, and pushed the hair out of her eyes. “Don’t get them started nagging for one.”

“I could install it,” Sonny said. “I could put it right there, off the edge of the porch, and you could sit there and look out at your sunflowers.”

Betty’s smile hadn’t changed. She looked down at her feet.

“Do you want some tea or something?”

Sonny didn’t answer. He stood there for a long moment, hands stuffed in his pockets, and Betty didn’t ask again. She lifted the boy from the pool and toweled him off, scolding when he stomped in the soft mud. The little girl giggled at her brother’s impertinence. Sonny remained at the edge of them with a stiff half-smile, hoping they would forget him, wishing insensibly that he could remain there, unnoticed, for the rest of the afternoon.