Lit Mags

“Forgotten” by Jonathan Baumbach

A story about competition at a dinner party

AN INTRODUCTION BY HILMA WOLITZER

Jonathan Baumbach is a master at portraying coupledom — both the coming together and the coming apart. On the first page of an early novel, Reruns, we’re told: “When Molly left, everything burned. I was vulnerable to the touch of air.” This sounds almost like a bit of adolescent angst about the end of a crush, but Molly is the narrator’s third wife, and his second wife is still vividly in the picture. And in a later novel, Separate Hours, two psychoanalysts counsel others while obsessively parsing their own shredding marriage. Passion, anger, competition, and regret are like those trick birthday candles that can’t easily be extinguished by a wishful breath. With its ambivalence and suspect accuracy, the memory of a love — if not the love itself — keeps on burning. Baumbach records these emotionally charged connections as if his life and the lives of his characters depend on them, in prose and content that’s by turn sly, wildly inventive, moving, and hilarious.

The politics of art and ambition enter the mix and the relationships seem casual and random, brought about, we’re told, by “the fingerprints of fate.”

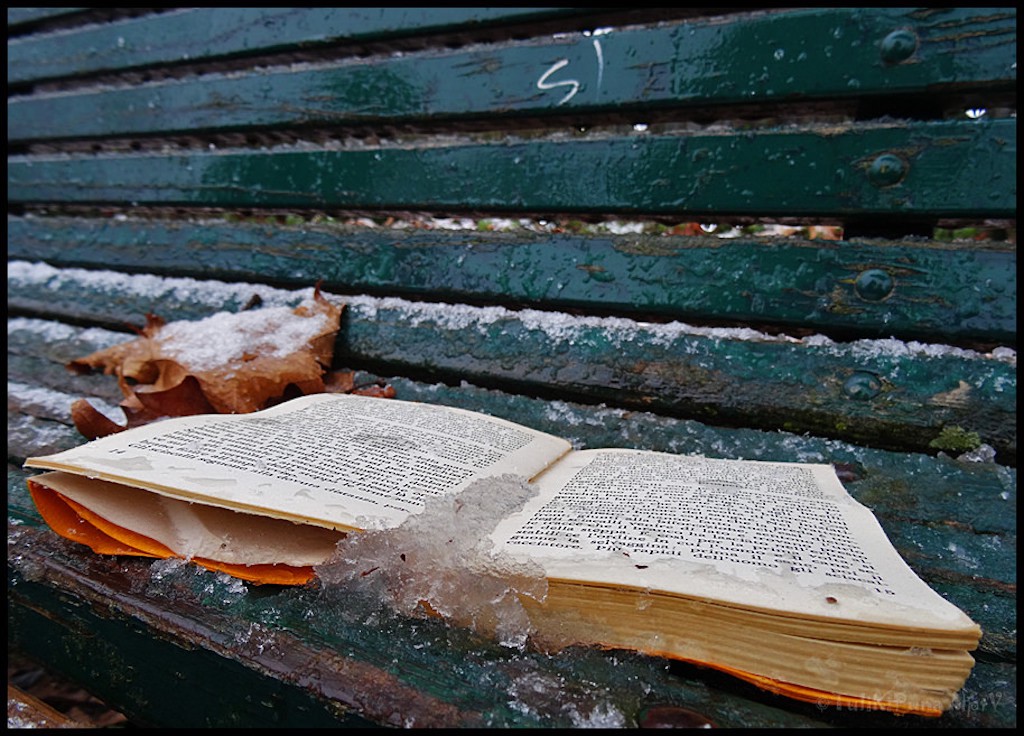

Now, in this fine new story “Forgotten,” an admitted lapse of memory (as the title warns us) informs the proceedings, which seem pretty arbitrary, anyway. It could all be about one thing or another, this couple or that — an updated take on the writer’s abiding concerns. The politics of art and ambition enter the mix and the relationships seem casual and random, brought about, we’re told, by “the fingerprints of fate.” The cast is large for a short story, including a famous novelist and “a mid-level celebrity in his own right” who stores his manuscript in a refrigerator “to protect it from nuclear attack or local conflagration.” People sleep around, or perhaps they don’t. The reader is given choices about what to believe has happened or is about to happen. Yet, our imaginations have been sparked by the writer’s; there’s genuine suspense in all this capriciousness. As promised, “We are frozen forever in a moment of unbridled expectation.”

Baumbach’s stint as the film critic for Partisan Review seems to pervade all of his work, which has a pleasurable cinematic quality reminiscent of Fellini or Rohmer. In “Forgotten,” the marriage disintegrates incrementally, “as if it were a slow motion replay of its burgeoning failure.” Reading Jonathan Baumbach, we’re like viewers in a darkened theater who will come out into the sunlight later, deliciously dazzled, quoting his best lines.

Hilma Wolitzer

Author of An Available Man

“Forgotten” by Jonathan Baumbach

Jonathan Baumbach

Share article

“Forgotten”

by Jonathan Baumbach

“We work in the dark — we do what we can — we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

— Henry James, “The Middle Years”

This, what follows, would be the story I planned to write, had I not, in sitting down to write it, forgotten what it was. As almost all my stories tend to be about love or its absence, I have to believe that this one, the temporarily lost and forgotten event, would fall or slide on its self-created ice into that approximate mode. It may be, this story, about a man and woman, who have been close friends for a long time, each married to another, who discover when it’s too late or almost too late that each has been the great love of the other’s life. That could be the story I had in mind, but I tend to doubt it. In the story I might have conceived, only one of the friends would discover that he loved the other and the other would resist believing her friend’s revelation. And then they would fall into bed and one or the other or both would regret acting impulsively. The needs of self, of perceived love, would not be repressed. The act itself, the acting out of long-denied imperatives, the violation of moral restraint, would be glorified, if uneasily acknowledged, by the trick of memory.

Or it could well have been the story of a couple, each married to someone else, who have an off-and-on affair over the years and finally decide that they want to be the main event in each other’s lives for as much time as they have left. It’s a delusion of course and they discover, in short order, that their relationship in order to survive needs the space their decision to live together has deprived them of. Or at least one of them feels that way. And the other, or the same one, much as he has justified his behavior by finding fault with his former spouse (who had taken him for granted, had failed to appreciate him sufficiently, had renounced sex or at least sex with him), feels debilitatingly guilty for causing his deserted wife pain. When he and his lover got together for their once a week liaison, there was a lot to talk about — it was a time of catching up — or talk itself was less important than the fast-fleeing time they had to make illicit love. Once they move in together, the exhilaration of urgency is hopelessly lost. So what comes of it, what’s the implication of the story? They can’t go back to what they’ve willfully destroyed. So they pretend to be happy in the new arrangement — they can’t do otherwise — and so suffer in begrudged silence, displacing their regret. This story is too unrelentingly sad. Even the ironies are unamusing. If this was the forgotten story, which I doubt, letting memory trash it, even if circumstantial, is undoubtedly the right choice.

Possibly the forgotten story had been about a married writer like the author, though younger, more like a former self, in residence one summer at an artist’s colony in upstate New York being visited, unannounced, by a married woman with whom he had a brief affair, which separation had ended several months earlier. The day of her arrival is the day, as it turns out, of a trip he has planned to take to the college town of Copington on the border between New York State and Vermont to visit this famous writer, I.M. Tarkovsky, whose latest novel he, Joshua Quartz, had reviewed in The New York Times. The review, admired by its subject, has elicited the celebrity’s invitation to come to dinner. Josh has no choice but to invite his inconvenient guest to join him on this trip, which will include another more established writer from the colony, a sometime friend and rival of the celebrated Tarkovsky, and an older woman painter, with whom the other writer, who is fucking his way through the female population of the colony, is presently involved. That’s the down payment of the story.

The story itself is an old one or a version of something that had actually happened that I had been holding on to in the hope of reimagining eventually into something livelier and more complex, but it is probably not the forgotten story of this occasion. That doesn’t necessarily exclude its possibility. If we are to go on with it — it may be all we have at the moment — we’re going to have to give our four characters greater definition. But then I think the reason the story has not been written before is that, beyond the charge of its given, nothing of consequence is in the cards for the two illicit couples making the trip. The character revelations are for the most part predictable and consequently trivial.

Say they get lost on the trip over, take a wrong turn which goes undiscovered for an extended period of time. Or they have a flat tire that neither of the men seems able to contend with. That the story takes a comic, even a farcical turn does not preclude it from an ultimate seriousness.

Or Harry Berger, the other writer on the trip, a mid-level celebrity in his own right, makes himself charming to Joshua’s aggrieved guest, offering the smart and sexy Genevieve an occasion to get back at Josh by making him jealous.

Or, more likely, they arrive uneventfully at Tarkovsky’s house in Copington, make small talk, munch peanuts, take a turn around the college grounds, return for a sit-down dinner of roast chicken, mashed potatoes and string beans. Perhaps not string beans, perhaps carrots and peas. The stack of sliced white bread on the table, even for the 1960’s, suggests a kind of unsophistication with potentially comic implications. Everyone is exceedingly civil until Mrs. Tarkovsky, Anna, mentions an interview given by Berger in which he off-handedly disparages one of Izzy Tarkovsky’s recent novels.

In defensive astonishment, Berger insists that he has been misquoted.

But Anna Tarkovsky comes back at him with a wholly different occasion in which Berger is also perceived to deprecate Tarkovsky’s work.

Berger mutters something unintelligible, furious at being put in the wrong, though in truth he is not a fan of Tarkovsky’s more recent work.

Genevieve, who has been silent throughout dinner — it is her mode these days not to give up words in the company of strangers — speaks up in Berger’s behalf in a gesture that surprises virtually everyone. “Harry didn’t volunteer these negative remarks you cite,” she says in her dreamy way. “Someone, some journalist looking to make noise, asked him a question which he tried to answer honestly. Journalists are always looking to create melodrama through overstatement.”

“Exactly,” Berger says.

“Let’s let the matter drop,” Tarkovsky says.

“Oh Izzy,” his wife says. “Stand up for yourself. These people aren’t your friends.”

“Let’s finish our meal,” Tarkovsky says. “That’s enough, Anna. Sha. I accept Harry’s explanation.”

Anna looks as if she has something more to say, but censors herself with notable displeasure. Izzy will hear about it again after these guests are gone.

To break the tension, Josh compliments Anna on her cooking.

“It was very simple,” she says. “I only do simple things.”

“Yes,” Lisa Strata says. “Simple is good. Making a meal is like making art. And art should always be simple. Of course cooking a meal is more useful than making a painting.”

“You may mean well,” Anna says, “but I don’t believe a word of what you say.”

During the dessert course (ice cream and cookies), Tarkovsky, apropos of nothing, delivers a lecture on the deficiencies and presumptions of the recent trend toward a “heartless formalism.”

“To deny the human in art, is, in the final analysis, to leave out everything that matters,” he says, stopping himself momentarily to take stock of his audience. No one has moved. Everyone is in place.

“I understand what you’re saying, Izzy,” Berger says, his willfully denied condescension showing through invisible cracks.

And where can the story go from here? The alert reader has already noticed that the story has virtually foreclosed itself.

Berger’s flirtation with Genevieve (or is it the other way around?) has no place to go while the characters remain, sitting at the dinner table, in Tarkovsky’s house on the Copington campus.

Rudimentary courtesy keeps the competitive tension between Berger and Tarkovsky from reaching the level of narrative-defining melodrama.

Tarkovsky has been Berger’s mentor, but Berger, insofar as he reckons his own accomplishment, has not only surpassed his former master but has become unwittingly privy to the other’s hitherto concealed weaknesses.

Josh, on the other hand, is still emerging as a writer and concedes a certain minor indebtedness to Tarkovsky’s early work. In the unacknowledged war between Berger and Tarkovsky, Josh is a relative neutral with one foot perhaps in the Tarkovsky camp. Lisa Strata is a bemused observer. Genevieve wants Josh, imagines she is in love with him, but remains, enclosed by silence, protected by vagueness, not quite explicable even to herself.

If there is no story to this point, there is at least a dynamic to its embryonic possibility.

After dinner, Tarkovsky will address himself to Josh away from the others.

“Are you working on a novel?” he asks him. “Isn’t that what you told me over the phone?”

“I am,” he says. “I’m hoping to have my rewrite finished before I leave Dadda.”

“Send me a copy when you’re ready to show it,” Tarkovsky says.

Josh merely nods, too pleased by Tarkovsky’s unexpected offer to find the appropriate language with which to thank him. “I’ll do that,” he says.

Later Josh will mention Tarkovsky’s offer to Genevieve, underplaying his elation in a way that gives it away twice.

“Congratulations,” she says. “He’s showing you that he’s a better person than Harry Berger.”

“Is that what you think?”

“It’s one reason,” she says, “but probably not the main one. It’s obvious that he respects you a lot.”

“He said that my review was the best thing ever written about one of his books.”

“You don’t need his praise,” she says. “You’re too good for that.”

Lisa Strata helps clear the table overriding Anna’s awkward protest that such a gesture is unnecessary. Berger wanders into the living room, checking out Tarkovsky’s library. He notes that two of his five books on these carefully alphabetized shelves are a notable absence.

And then, following an after-dinner drink, which Josh alone foregoes, it is time to return to Dadda. Handshakes are exchanged. This is not a period in which men embrace in public. Anna remains in the kitchen, calls out a goodbye when it becomes clear that Izzy’s guests are clearing out.

And still there is no story of consequence beyond what I think of as the unacknowledged unspoken. Our story, if it ever claims itself, is embedded in unimagined, perhaps unimaginable possibility. Of course there is the trip back to be dramatized with Lisa and Harry in the back seat, amusing themselves at the Tarkovskys’ expense. Josh, on the other hand, is an unwitting eavesdropper, ashamed of his unwillingness to defend the older writer from his cruel satirists. There is some compensation, however, in his situation. He can imagine writing the story of this dinner at the Tarkovskys one day to Berger’s disadvantage And there’s the more immediate compensation of Genevieve’s sly hand in his lap as he drives. They will have great sex that night, perhaps their best ever, fueled by the fallout of the visit. Genevieve will leave the next day to attend graduate school in California and they will not see each other again for almost a year.

Berger and Lisa Strata will sleep this night in their own rooms, which one assumes, has been Berger’s decision, wanting to keep something in the tank for the final gestures of his book, which is stored each night in a refrigerator to protect it from nuclear attack or local conflagration. We are still in the era of typewriters and longhand and it is not easy to protect ones creations from the unforeseen.

Lisa will reward this slight by doing a painting of Berger from memory, showing the back of his head neatly coiffed, doubled in surreal surprise by a mirror image of the same. The painting entitled “The Other Side of Fame” will be a critic pleaser in her next one-woman show, singled out for praise in virtually every review.

Tarkovsky will write a generous blurb for Joshua’s first novel which will appear in large type on the back cover and, had there not been a newspaper strike at the novel’s appearance, would have played a significant part in the book’s reception.

In short order Berger will publish the novel he had completed at Dadda and he will win a Pulitzer for it, his first of several.

None of these consequences is a particular surprise to the attentive observer and none is a direct consequence of the trip from Dadda to Copington to visit I.M. Tarkovsky.

Something seems to have been left out, something important that has slipped our attention.

Eighteen months after the Tarkovsky visit, Joshua will separate from his wife and move into a furnished room not far from Genevieve’s loft apartment in what will later be known as the East Village. A year or so down the road, a time punctuated by a series of agreements never to see the other again, Joshua and Genevieve will move in together, marry, have children, separate, divorce.

Let’s backtrack a moment, not all the way back to that summer at Dadda, which is at the center of our narrative, but back to a period when Joshua and Genevieve have temporarily broken up.

During that period, Berger and Genevieve run into each other circumstantially and Berger bestirs himself to be charming, remembering how smart and sexy Genevieve seemed that evening at Tarkovsky’s. As they are going in the same direction, they walk together for a while at Berger’s urging. When they are about to separate, he invites her to come up to his place for a glass of wine. Genevieve declines — she has an appointment with her therapist in twenty minutes — but promises she will come by another time. Berger takes her number, but never gets around to calling. Two weeks later, they run into each other again at the very moment Berger is wondering where he had deposited the slip of paper with Genevieve’s number on it.

This second meeting, in which the fingerprints of fate seemed notable, offers the opportunity for each to make good on failed promises. “I’m just around the corner,” Berger says. “Why don’t you come up for a glass of wine.”

“I don’t know,” she says, which is not so much a rejection of his offer as an opportunity for Berger to make his petition easier for her to accept.

“What don’t you know?” he asks. “What makes this such a hard decision for you?”

“One glass of wine and that’s it,” she says. “Okay?”

“Absolutely,” he says. “I never urge anyone to do anything she doesn’t want to do. I think we understand each other.”

And so they walk together (and apart) to Berger’s brownstone duplex apartment , which is actually three blocks away from where they had been. They chat as they walk. He seems interested in her story, which in her telling is never quite the same story twice.

What is Genevieve thinking? one wonders. She can always say no, she might be telling herself, if it comes to whatever it’s likely to come to. If she doesn’t say no — perhaps he won’t even make a pass — she can always tell Josh she had, assuming that she and Josh get together again, which remains an angry hope and an inescapable expectation. More to the point, she gets off on living dangerously, she always has, so however it plays out, the frisson of her visit is likely worth whatever the ultimate price of admission.

The apartment is unexpectedly incomplete, bookcases partially filled, unpacked boxes on the floor, paintings guarding their potential space on the wall. This is mostly true of the living room where they sit, facing each other across an oversized slate coffee table, drinking expensive French wine.

“How are things going with you and Josh?” he asks her.

“Okay,” she says. “Why do you want to know? I wouldn’t think that would interest you.”

“Everything about you interests me,” he says.

“You’re just making conversation,” she says.

“Yes,” he says. “Do you like the wine?”

She knows or thinks she knows or doesn’t know she knows that if she wants to be in charge of herself, a second glass of wine is a mistake. She knows that, doesn’t she? She has cautioned herself in advance not to have more than one glass of wine, though at the same time she wants to be open to the moment, to collaborate with the moment in making her decision.

It is already too late. She has with a self-effacing laugh let him fill up her glass for a second time.

She also knows, or some part of her does, that if she sleeps with Berger, which is the obvious end game of his determined kindness, that Josh would hold it against her virtually forever. That’s his problem of course and only marginally hers. And it is very good wine to which the label attests and her taste buds insistently acknowledge.

And still she thinks, not now, not this time, or why not? She sips carefully, savoring the wine.

“How is it you’re not living with anyone?” she hears herself ask him.

“I don’t know,” he says. “That’s just the way it is at the moment.”

“Is it?”

“It is,” he says. “Do you think I should be living with someone?”

A laugh escapes her, occupies the space between them. She wonders at the source of the laugh and considers, against her saner judgment, turning her head. “It’s none of my business,” she says. “With someone like you, it probably makes no difference anyway. Whoever you’re with, you’re always alone.”

Berger says nothing, looks away, looks back, looks like someone on the deck of a ship with the wind blowing in his face. “That’s a cruel thing to say,” he says. “It’s also very shrewd, possibly even true.”

She feels flattered by his compliment, though it is not an unmixed pleasure, and she chokes back a ‘thank you,’ which is all too readily and embarrassingly available.

And when is he going to make his move? she wonders. Berger may well be wondering the same thing himself.

“I’d better go,” she says.

“Must you run off? Finish your glass first.”

“It’s wonderful wine,” she says. “Are you trying to get me drunk?”

“Do I get any points for making that admission?”

Another laugh gets the better of her private decision not to be amused. “I don’t give out points,” she says. “If I did…”

He stands up. “Did you have a coat?” he asks. “I really have to get back to work. We’ll do this again soon, I hope.”

“My coat, it’s lying on one of your boxes,” she says, unsure of what’s going on.

He holds her coat for her and she gets up, feeling a bit unstable, to accept his gesture, wondering if he is protecting her from herself. Nevertheless she feels, as she works her arms into her coat that she’s the one that’s being deprived. At the door, where she initiates a kiss, she notices that her wine glass, her second glass of wine, perhaps her third, is approximately half full.

She will go to bed with Berger on her next and last visit to his apartment. And ten years later, she will confess it to Josh, who is her husband now, during a stay in the south of France.

The confession is the beginning of the end of her marriage, which will last another two and a half years, coming apart as if it were a slow motion replay of its burgeoning failure. She knows Josh will never forgive her for sleeping with Berger and she will grow to hate him for being so unforgiving.

This is the forgotten story or at the very least its stand-in. For the moment, if you can imagine it, we are back in Josh’s five year old Volvo, his inamorata Genevieve in the passenger seat, Lisa Strata and Harry Berger in the back, en route to Copington Vermont to have dinner at the home of the celebrated writer, I.M. Tarkovsky. We are frozen forever in a moment of unbridled expectation.