Books & Culture

Forgotten Woman: The life of Misuzu Kaneko

Tracing the path of a Japanese poet from fame to obscurity and back

In the Higashi Otani cemetery built on a hillside in Kyoto, there is a small gravestone near the stairs that my aunt Michiko and I always pass on our way upwards to my grandparents’ grave. Weathered and untended in a crowd of closely packed stones on terraced ledges, it is easily overlooked. Chiseled on its front is the name of a woman, Sakurai Satoe.

I’ve always wondered who this woman was, Michiko would say. She’d noticed the stone forty years ago, when her mother was interred there. It was distinctive for a few reasons — one, the stone was small and perched near the stairs where passersby could see it if they were attentive; two, the stone was not part of a family group and contained only the gently incised name of a woman; and three, that name was evocative and poetic. Sakurai means ‘well of cherries’ and Satoe means ‘place in the countryside.’

She’d noticed the stone forty years ago, when her mother was interred there.

The woman was likely unmarried. Michiko imagined she worked as a geisha in the city. Kyoto, after all, is famous for these female entertainers whose artistry and elegance is world-renowned. When I lived in Japan in the eighties, I sometimes caught sight of a geisha or maiko in the narrow cobblestone alleyways of Pontocho, and wondered about their mysterious lives deep in the heart of the city. Only the well-heeled and privileged could afford the services of geisha. Perhaps Sakurai Satoe’s death was commemorated by a lover or another ‘sister.’

I’d been to this cemetery only a few times. My interest had been piqued by my grandfather’s mention of it in his memoir, which I translated with Michiko in 2007.

At first, I didn’t pay much attention to Michiko’s remarks about this solitary woman’s grave, but on our most recent visit, we noticed something odd about the gravestone. Looped around its base with string was a white laminated sign stating that the stone would be removed in the near future as there had been no indication of its being tended. It was likely whomever had been paying the annual fees to the graveyard administrators had stopped doing so. I knew the fee was nominal; my aunt and her siblings continued to pay for their parents’ gravesite.

Looped around its base with string was a white laminated sign stating that the stone would be removed in the near future as there had been no indication of its being tended.

On this occasion, Michiko and I, along with my fourteen-year-old daughter, had just returned from Michiko’s youngest daughter’s wedding in Tokyo. Michiko had brought with her the floral tribute bouquet that had been given to her and her husband by the couple. She thought it would be fitting to bring these flowers to our maternal ancestor.

My daughter was far less excited about visiting her great-grandparents’ grave than going to a wedding. She quietly tagged along as we mounted the stairs with our flowers and water for the vases. When we stopped in front of the grave stone of the single woman, Michiko explained the sign to my daughter. She shrugged and said, “If you’re no longer remembered, you’re no longer living. They’ve got to make room for others, don’t they?”

She shrugged and said, “If you’re no longer remembered, you’re no longer living. They’ve got to make room for others, don’t they?”

It was a startling comment. My daughter spotted more of the signs dotting the terraced plots. It seemed the graveyard authorities were cleaning house by taking stock of their neglected dead. Making room for others.

How was it that the last evidence of one’s life could be so easily removed? Would this be the last time I would see this stone? Then Michiko noticed something on the sign. The date for the stone’s removal had come and gone. My daughter suggested we put some flowers into the vases to give the workers pause. Plucking two pink roses from the tribute bouquet, we set one on either side of the stone as if to say, this woman, Sakurai Satoe, has not been forgotten after all. Not by us, at least.

In the spring of 1923, a young woman working in her uncle’s bookstore in the coastal city of Shimonoseki in Yamaguchi prefecture sent some poems she’d written to a few children’s magazines in Tokyo. She had a rather common given name, Teru, but being well-read and of a somewhat fanciful nature, she conceived of a pen name: Misuzu. The name was derived from the word ‘misuzukari’ which means the ‘reaping of bamboo grasses’ and was a classical allusion used in ancient Japanese poetry.

She had a rather common given name, Teru, but being well-read and of a somewhat fanciful nature, she conceived of a pen name: Misuzu.

The selection of a pen name by this talented young woman would both ensure and obfuscate the woman’s identity from the point of utter obscurity to nationwide fame decades after her death. Like Sakurai Satoe’s gently carved name on the gravestone, Misuzu Kaneko’s name would appear like a cipher as the author of a few noteworthy poems found in children’s magazines of the period with little else as evidence of her life until its re-discovery decades later by literary scholar, Setsuo Yazaki.

Misuzu was just twenty when she sent out her poems, the age when the Japanese celebrate entry into adulthood. Only a few months earlier, she had been living with her grandmother and older brother in the nearby town of Senzaki where she had grown up in a family bookstore run by her widowed mother, Michi. Her father, a bookstore manager, had died overseas in China when Misuzu was three. Since his widow Michi was saddled with the care of three young children (Misuzu was the middle child), the youngest boy whose name was Masasuke, was adopted out to Michi’s younger sister, Fuji, and her sister’s husband Matsuzo Ueyama at the age of one. Matsuzo was the owner of all the bookstores in the family. He and Fuji had no children and were happy to adopt the young Masasuke, whom they hoped would carry on the family business. Around the time Misuzu turned sixteen, her aunt Fuji died, and Misuzu’s mother went to the city to remarry her sister’s husband, Matsuzo. Misuzu remained behind so that she could finish her schooling — namely, high school, which was unusual for a girl of her time to complete — before being called to work in Shimonoseki at her Uncle Matsuzo’s bookstore.

Reunited with her mother, and working independently in the familiar environment of the bookstore, Misuzu was truly happy.

It was in this heady atmosphere of the city — Shimonoseki was a bustling gateway to China and Korea at the time — where Misuzu began writing in earnest while minding a small branch store of the family chain on her own. Reunited with her mother, and working independently in the familiar environment of the bookstore, Misuzu was truly happy. The acceptance on the first try, of five of her poems by four magazines in the faraway urbane capital of the country was quite an accomplishment for the young woman. In particular, Misuzu had garnered the attention of the sophisticated literary editor, Yaso Saijo, who believed he had discovered a new and rising talent. On publication, Misuzu soon received fan mail, and letters of admiration were quickly printed up by the magazine’s editorial.

Children’s magazines were fashionable in the Taisho era of the 1920s in Japan; they frequently published the work of some of the best literary talent in the country at the time. Writing for children was not seen as beneath writing for adults, rather it was seen as an outlet for the kind of creativity and innocence children were perceived as inherently possessing. Do-shin was the word used to describe a child’s innocent heart to which do-wa (children’s stories) and do-yo (children’s poetry) could speak. Everyone who had been a child had at one time possessed ‘do-shin’ and could therefore experience again through do-wa and do-yo that state of innocence, purity and curiosity that was the essence of a child-like consciousness.

Writing for children was not seen as below that for adults; rather it was seen as an outlet for the kind of creativity and innocence children were perceived as inherently possessing.

Talented musicians, poets, and artists of the time were exploring this avenue of expression with enthusiasm. Misuzu, herself, a product of the changing times — well-educated and raised in a bookstore by a conscientious single mother — found herself among an admiring milieu of like-minded artists who appreciated her poetry. Masasuke, Misuzu’s younger brother, was also enthusiastic and musically gifted. Since they had grown up together (as ‘cousins’ — Masasuke did not know he was Misuzu’s brother) the two often collaborated with one another. Masasuke, being younger, was impressed by Misuzu’s achievements and was inspired by her writing. Not long after Misuzu moved to Shimonoseki, Masasuke went to Tokyo to get training in the book trade, during which time he continued composing music for children. One of his compositions was published in the children’s magazine Akai Tori in April, 1924. Misuzu was excited to hear this news and encouraged him.

In the meantime, a man named Keiki Miyamoto began working in the family bookstore. Misuzu’s uncle Matsuzo kept his eye on the young employee as a possible match for Misuzu for he was becoming increasingly worried that his adopted son, Masasuke was falling in love with Misuzu. How aware Misuzu was of her uncle’s plans are unknown; she was perhaps, in some ways, oblivious, focused as she was on her writing career.

She had joined a children’s writing group in the absence of editor Yaso Saijo, who had gone to France but who had been a great advocate of talented new writers like herself, and she also started assembling a personal collection of poems called Rokanshu (A Collection of Precious Stones). The journal was organized in monthly chapters. Notably, the first poem selected was a translation of Christina Rosetti’s “The Lowest Place,” which she caught glimpse of in an expensive edition sold at her bookstore (which, ironically, she could not afford) but could copy from by daintily lifting up its cover and jotting the words down in her notebook:

The Lowest Place

Give me the lowest place: not that I dare

Ask for that lowest place, but Thou hast died

That I might live and share

Thy glory by Thy side.

Give me the lowest place: or if for me

That lowest place too high, make one more low

Where I may sit and see

My God and love Thee so.

I quote the poem here as an example of Misuzu’s wide reading, one which shows her attraction to a religious work that extols humility. Another significant factor in Misuzu making this selection was that Yaso Saijo had already translated Rosetti into Japanese before, and had compared Misuzu to her. Misuzu, being a conscientious reader would likely have read anything he’d written or translated in appreciation of his literary sensibilities.

In the summer of 1925 , Misuzu’s best friend Hohoyo Tanabe died suddenly; this was deeply distressing to Misuzu. Hohoyo had returned to Senzaki from Korea where she had been living with her husband, to attend her ailing mother. While looking after her, she fell ill herself and died. She was pregnant with her first child who perished with her. Hohoyo and Misuzu were close and shared a love of poetry. Misuzu had dedicated her first collection of poems Kowareta Piano — “A Broken Piano” to her. And Hohoyo herself had recently published in Akai Tori. While in the midst of Misuzu’s mourning, Matsuzo finalized his arrangements for her marriage to Miyamoto to which obedient Misuzu complied. The wedding was to occur in Shimonoseki the following February.

On hearing of these plans, Masasuke felt uneasy. He made a special trip out to Senzaki where Misuzu was staying that winter to dissuade Misuzu from agreeing to this match. He also had to confirm the unsettling feelings he had for her. Was it true that she was his sister and not his cousin as he presumed all along? Earlier he had learned of his adoption by seeing his army draft papers, but now it dawned on him that Misuzu’s mother might well be his own, making Misuzu his sister. He needed to confirm this to be sure.

He also had to confirm the unsettling feelings he had for her. Was it true that she was his sister and not his cousin as he presumed all along?

Misuzu admitted to Masasuke that in fact, she was his sister. Having settled that, Masasuke then began to express his feelings of opposition towards loveless, arranged marriages. “Well, fine then,” he said. “It’s okay if you get married. But isn’t there anyone else who you love? If there is, why don’t you marry that person?” Misuzu’s oblique response was, “That person is the one wearing black clothes and holding a long scythe.” She was making a reference to the Grim Reaper. The comment would turn out to be prescient.

Clearly, Misuzu was not looking forward to the arrangement, but rather, was resigned to it. She knew she was of marriageable age, and was aware of her mother’s concern that if she didn’t marry soon, she would not find anyone. Misuzu also wanted to respect the wishes of her uncle Matsuzo; not agreeing to the arrangement would put her mother in an awkward position with him, something Misuzu did not want to risk. Besides these reasons, it is also possible Misuzu considered Masasuke’s artistic ambitions. Even though he was expected to take over the family bookstore, Misuzu wanted him to be free of his responsibility for it; if Misuzu married Miyamoto and things went well with Miyamoto working in the business, Masasuke could pursue his dreams as a composer without worrying about the future of the bookstore.

“Well, fine then,” he said. “It’s okay if you get married. But isn’t there anyone else who you love? If there is, why don’t you marry that person?”

In an age when arranged marriages were the norm, Misuzu took the conventional route for unselfish and compassionate reasons. Thinking of the needs of others in the strict and gendered hierarchy of obligations and responsibilities of women to men, and young to old, Misuzu did what she felt was right for everyone but herself. No one could have imagined just how badly this union would turn out to be until it was too late. Miyamoto turned out to be a disaster; he was a frequenter of brothels, had been involved in unsavoury business practices as a stockbroker, and had even tried killing himself with a prostitute in a double suicide attempt at which only he survived. If there was any love to be had in him for a woman, it would certainly not be for the bookish young niece his employer had arranged for him to marry. No, this was a marriage of convenience, securing his position in a place of well-regarded and reputable employment.

The couple started their life in the second floor of the bookstore in Shimonoseki in February of 1926. At first, Misuzu tried hard to be a good and dutiful wife. Her earnest, child-like optimism is made evident here in her much-loved poem “To Like It All.”

To Like It All

I want to like everything —

onions, tomatoes, fish —

I want to like them all.Everything my mother makes

for our meals.I want to like everyone —

doctors, crows —

all of them, too.Everything and everyone in the world

God has made.

Not long after her wedding in February, Misuzu’s poetry experienced a resurgence in popularity and she was published several times in the following months throughout the spring. Later on, in July of that year, Misuzu’s poems Tairyo (The Big Catch) and Osakana (Fish) were chosen for the acclaimed annual Nihon Doyo Shu (A Collection of Japanese Children’s Poems) edited by members of the preeminent professional organization of children’s poetry writers, Doyo Shijin-kai, several of whom were well known writers of the age such as Toson Shimazaki, Izumi Kyoka, the editor Yaso Saijo, and Akiko Yosano. Later, an invitation was extended to Misuzu to join the group, making her only the second woman admitted into the association after the well established Yosano, who was now in her forties.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing between the men in the bookstore. Masasuke and Miyamoto did not work well together. After an argument with Miyamoto over business practices, Masasuke abruptly left Shimonoseki to join Misuzu who was in Senzaki on an errand. Matsuzo believed Miyamoto had driven his beloved son Masasuke out of the business and confronted him. When Misuzu returned to the bookstore, she tried to mediate between her brother, uncle and her husband, by calmly advocating for Miyamoto. The result of this intervention, however, made things worse. Miyamoto became haughty and arrogant, to the point of brazenness; he invited the women he’d been seeing on the side to visit him openly at the bookstore. This was the final straw for Matsuzo. It was now evident that he had chosen the wrong marriage partner for his niece. He proposed to Misuzu that she divorce him at once, but it was too late. Misuzu was pregnant.

He proposed to Misuzu that she divorce him at once, but it was too late. Misuzu was pregnant.

Miyamoto was fired. He left with the intent to start his own business elsewhere, and even though her uncle told her she could remain at the bookstore, the pregnant Misuzu decided to accompany her husband. On November 14, 1926 Misuzu gave birth to a girl whom she named Fusae. By that time, Miyamoto’s new business venture was failing and there was again strain in the marriage.

The following summer, editor Yaso Saijo was going through Shimonoseki enroute to Kyushu; he arranged to meet Misuzu at the train station. The dapper, well-heeled cosmopolitan editor was startled to see a disheveled young woman dressed in dull cotton kimono with an infant strapped to her back. The gentle soft-spoken woman said, “I’ve come over the mountains just so I could meet you in person. Now I will be going back over the mountain again to go home.” This would be the only time Yaso Saijo would set eyes on the poet whose work he admired so much.

The dapper, well-heeled cosmopolitan editor was startled to see a disheveled young woman dressed in dull cotton kimono with an infant strapped to her back.

In the fall of 1927, the family moved again this time because of financial difficulties to Kyushu to where Miyamoto’s parents lived. The stay was short; they returned to Shimonoseki within a couple months, this time for Miyamoto to start a grocery business. By the end of the year, Misuzu had contracted gonorrhea from her philandering husband.

In early spring, poet Tadao Shimada came to visit Misuzu at one of the family’s branch bookstores in the new fashionable department store in Shimonoseki. Misuzu demurred; she was ill, bedridden in fact, and she did not want Shimada to see her in her current condition. Moreover, her husband had expressly forbidden her to write any poetry or correspond with her brother, colleagues, editors or fans. When her alma mater high school requested a contribution for their newsletter, Misuzu sadly wrote back:

The wings of my imagination which soared as high as the sun have now been clipped. All that is left is one foolish mother. I remain a bookworm who only knows the world that exists in books and makes no effort to understand the outside world. My sole happiness lies in playing with my child and in opening books.

Misuzu decided to compile a complete manuscript of her poems to give to Yaso Saijo and Masasuke. Despite her being ill, however, Miyamoto moved the family again — their fourth move in two years, and the second in eight months. Misuzu wrote of her fatigue to her mother that September; she could barely undertake even the slightest of house chores without having to recover for days afterwards. Ashamed, she told no one of her disease. In those days, without antibiotics, treatment was not effective. Despite this, or perhaps even because of the illness, Misuzu did manage to complete her manuscript at the end of October 1929. Even as she completed her goal, however, there was a weariness in her tone as expressed in this poem:

Personal Note After Finishing my Manuscript of Poems

It’s done

It’s done —

My little book of poems.

Not to say I’m proud,

but my heart does not dance,

and I feel lonely.

Now summer is over

And with autumn too, about to end,

I pick up my needle and work on a cloth,

feeling empty.

To whom will I show this book?

Even I feel it lacks something.

How lonely!

Without even climbing the heights

have I come back —

the mountain peaks shrouded in clouds.

But still, even knowing this,

have I stayed up late into the autumn night

writing intently under the lamp.

What shall I write tomorrow?

Ah, how lonely!

By early 1930, the weakened Misuzu now separated from Miyamoto, was living with her daughter, Fusae at her mother and uncle’s place where her mother could help with the child’s care. Unbeknownst to Misuzu, Miyamoto had gone to Tokyo. The couple’s divorce was finalized in 1930 but Miyamoto insisted on getting custody of their daughter as was his right under the law, knowing full well that Misuzu would refuse. By threatening to claim custody of the child, he planned to extort money from the family. He wrote to Misuzu that he would come for Fusae on March 10.

The day before his expected arrival, Misuzu went to get a final portrait of herself at the Miyoshi Photo Studio in Shimonoseki. On her way home, she bought a package of sakura-mochi, a favorite family treat made of sweet bean paste and sticky rice wrapped in a salted cherry leaf. She shared it with her daughter, and then lovingly bathed her before putting her to bed. Her mother noted nothing unusual in Misuzu’s behaviour that night; her last words to her mother were about Fusae: “She looks so cute when she’s asleep.”

Her mother noted nothing unusual in Misuzu’s behaviour that night; her last words to her mother were about Fusae: “She looks so cute when she’s asleep.”

That night, Misuzu wrote three wills — one for her husband, one for her mother, and one for her brother. The three documents no longer exist so it is difficult to corroborate what was written, but witnesses say, she urged her husband to give up his custody of Fusae to her mother who was the only person she could trust for her child’s upbringing. She wanted Fusae to have a ‘rich spirit’ rather than to be provided for only materially. She then apologized to her mother for being a poor wife who could not prevent her husband’s infidelities, and to her brother, she gave words of encouragement to pursue his dreams as an artist in Tokyo representing their family.

After she wrote the wills, she took an overdose of the sedative, Calmotin, a common drug used by writers for committing suicide, and died on March 10, 1930 at the age of twenty-six.

From then on, the poet Misuzu Kaneko was completely forgotten.

It was in the mid-sixties when poet and literary scholar Setsuo Yazaki was perusing some old children’s magazines in the library that he encountered Misuzu Kaneko’s poem “Big Catch.”

Big Catch

At sunrise, glorious sunrise

it’s a big catch!

A big catch of sardines!

On the beach, it’s like a festival

but in the sea, they will hold funerals

for the ten thousands of dead.

Yazaki was struck by the poem. Who was this poet who could empathize with even the fish in the sea? When he went to investigate, he could find little information about her. Misuzu was a pen name, and ‘Kaneko’ was the maiden surname of the poet. And although he could trace the poet back to city of Shimonoseki from where she submitted her poems, the bookstore where she worked was no longer in existence. Still, Yazaki persisted in his search. In 1982, he got a lucky break — the poet’s brother, Masasuke was alive and in his seventies. He presented Yazaki with some photos and three battered pocket diaries containing 512 poems, most of which were unpublished.

At the time of Yazaki’s discovery, he serendipitously met up with a colleague who would later head up a publishing company called JULA Publishing Bureau. Founded in 1982, JULA was the publishing arm of the Japan Children’s Literature Institute. Yazaki gave over all the work he had recovered to the press for publication. JULA published a six-volume set of all the poems as well as Yazaki’s biography of the poet, The Life of Children’s Poet Misuzu Kaneko — a meticulously researched work that is an authoritative and seminal account of the poet’s short life that many have consulted, myself included.

Once released into the world, Misuzu’s poetry quickly gained popularity in Japan, so much so that there is now a museum dedicated to her memory in her hometown of Senzaki. Not only have there been books published, but films have been made about her life as well as music composed to her poetry. In 2011, Misuzu’s poem “Are You An Echo?” received nation wide attention when it was aired on TV during the tsunami-earthquake crisis.

In 2011, Misuzu’s poem “Are You An Echo?” received nation wide attention when it was aired on TV during the tsunami-earthquake crisis.

My own encounter with Misuzu’s poetry began in 2010 when I was working as a blog contributor and reviewer for the now defunct multicultural children’s literature website, PaperTigers. I was instantly gripped by Misuzu’s work. She was extraordinarily perceptive and her viewpoint on the world of living things was unique, unlike anything I’d read before in children’s poetry in English.

At the time of my discovery of Misuzu Kaneko’s poetry, there were only two books of her work translated into English — D.P. Dutcher’s Something Nice and Midori Yoshida’s Rainbows on Eyelashes. Both were published by JULA. Although the books were competent translations of Misuzu’s most famous poems, they left me wanting more. So I decided to sharpen my skills at translating Japanese poetry acquired during my research scholarship days in Tokyo in the late 80’s to reveal more of this woman’s poetic treasure in English. I enlisted the aid of my Aunt Michiko, who had helped me translate her father’s (my late grandfather’s) memoir into English. Michiko wanted to improve her English by delving into more of Misuzu’s work through the act of translation. We set up an impromptu arrangement over e-mail, with Michiko selecting poems she liked from the six-volume set of Misuzu Kaneko’s poetry she had taken out of the library and sending them to me with an initial draft of a simplified English translation. I would read the translation and compare it to the original, and then tweak the English to make it read better for a native English reading audience.

This process of translation, although slow, was always delightful.

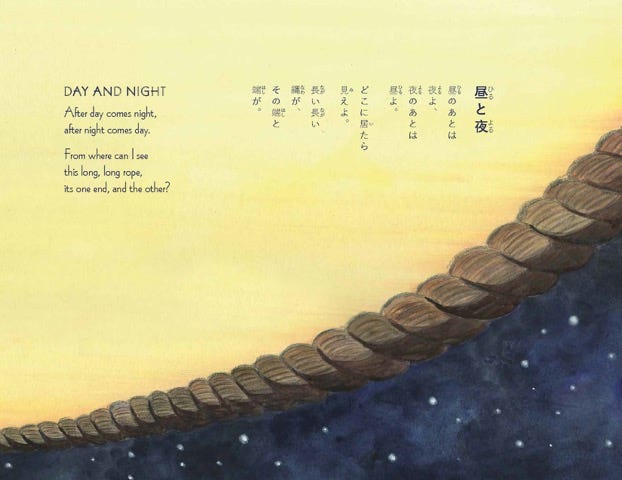

This process of translation, although slow, was always delightful. Time after time, with each poem translated, Michiko and I would be startled anew into another dimension of Misuzu’s imagination. For example, in one poem she personifies Last Year as a ship quietly leaving the harbor; in another poem, she offers words of comfort to a carp in a pond gazing enviously at carp streamers in the sky. Misuzu had a great capacity for empathy and compassion for all living creatures. And her attentive and watchful gaze often went to the unattended or the invisible. She noticed things other people didn’t and pondered them. Moreover, she was curious. In another poem, she contemplates the nature of time by reflecting on how night and day follow one another like a rope. For me, reading Misuzu sometimes felt like reading Blake. Her poetry was simple enough Japanese for a child (or a non-Japanese foreigner) to read, but only in translating it did I experience the depth and breadth of her unique vision.

Like Sakurai Satoe of the neglected gravestone, Misuzu Kaneko was nearly forgotten. But would that have mattered to her really? It seemed to me she wrote poetry for the sheer pleasure of it and that her success, at least initially, came as a surprise to her. I felt as if Misuzu wrote purely, and by purely, I mean without the trace of a self-conscious egotism. She wrote with the kind of innocent abandon I wish I could have again as a poet. Selfless and without guile, attentive but uncloying, she wrote poems about the world without the weight of its meaninglessness burdening every syllable. She embodied that perfection of the poetic ‘I’ that observes and becomes the thing it observes in compassion and harmony with it.

She embodied that perfection of the poetic ‘I’ that observes and becomes the thing it observes in compassion and harmony with it.

This is not to say Misuzu was unambitious with her work. Even as she was ill, itinerant with a philandering husband, and a mother of a young child, she steadfastly continued through extreme conditions to produce a final manuscript of her work to give to those who had appreciated her poetry the most — editor Yaso Saijo and her brother, Masasuke. She was grateful to them and probably believed she owed it to them to give them all of the work she had composed thus far in her short life. And when she finally completed this task, no doubt at some cost to her health, she turned joyfully at hand to record the words of her three year old daughter in a book she called Nankindama, or “Glass Beads.” Misuzu was a poet through and through, a woman besotted with words and their power to express her deepest feelings of love, compassion and gratitude. She wrote, not so much to be remembered, as to not forget how delightful and wondrous the world could be for a child, and that is why her poetry is so celebrated in Japan today.

(Endnote: The biographical material on Misuzu Kaneko was written in consultation of Setsuo Yazaki’s biography Doyo Shijin Kaneko Misuzu no Shogai (The Life of Children’s Poet Misuzu Kaneko) published by JULA Shuppan, 1993 and Elizabeth Keith’s Masters Thesis (2002) for the University of Hawaii entitled Kaneko Misuzu and The Development of Children’s Literature in Taisho Japan.)

Read more about Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, published by Chin Music Press.