interviews

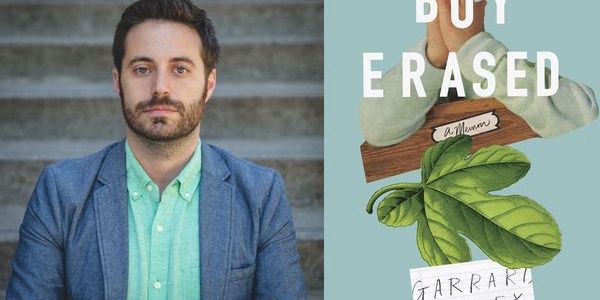

Garrard Conley on ‘Ex Gay’ Therapy, the Church and His New Memoir, Boy Erased

Garrard Conley’s new memoir Boy Erased (Riverhead, 2016) is a coming out story that involves rape, condemnation, loss and love. Conley was outed as gay during his freshman year of college to his mother and his father, a Christian Baptist minister in small-town Arkansas. The story interweaves Conley’s experiences with a high school girlfriend who hoped they would marry, the abuse he suffered by another boy in college, and the trauma of a church-supported conversion therapy program that promised to “cure” him of homosexuality. In 2004, he volunteered to attend Love In Action, an ‘ex-gay’ therapy facility, in order to save his family, but he eventually fled the facility in order to save himself from committing suicide. In spite of the struggles he faced growing up gay he has emerged triumphant, which is why Boy Erased will have a strong and positive impact on readers tackling similar issues concerning faith, family and community.

I met Garrard at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in 2015 and liked him immediately. He’s the guy you tell all your problems to and take home for Thanksgiving. He is amiable, sincere and compassionate. He’s also fun on a dance floor. We met again at the AWP conference in Los Angeles, but it wasn’t until he was home in Sofia, Bulgaria, where he lives with his boyfriend and teaches English to high school students at the American College of Sofia, that I had the opportunity to phone him for this interview about Boy Erased.

Andrea Arnold: Anyone would find it difficult to be forthright in a book about his or her early sexual experiences and yours were heartbreaking and traumatic. As someone who also writes fiction, why did you choose to write Boy Erased as a memoir instead of a novel, where an author can hide behind fictional characters?

Garrard Conley: I started writing the first essay for the book in a nonfiction class at UNC-Wilmington. The professor asked all of us what part of our lives we would be writing about in his class. Before that moment I had never considered writing about ‘ex-gay’ therapy or my childhood, but I blurted out some details of my life and everyone in the room leaned forward to listen. The interest was palpable. One girl said, “How is it even possible that this still happens in 2004?” Her words were my first indication that the story might be more important as a memoir than as a novel.

I worried that as a piece of fiction the story might seem exaggerated. In fiction you can get away with covering up the nasty parts of an autobiographical story or making the prose subtle. In nonfiction, however, you have the chance be explicit and say, ‘This stuff actually happened to me.’

…one person asked, “How can a parent do that to a child?” That question has followed me throughout the entire process of writing the book.

The other indication that this might turn out as nonfiction came from a conversation I had at a café with friends at Columbia University in New York. I was visiting a friend, and someone asked about Arkansas, so I told the group a bit about my childhood. People at the table leaned forward just as they had at UNCW, and one person asked, “How can a parent do that to a child?” That question has followed me throughout the entire process of writing the book. My mom has also been asked this question many times, and she almost always cries and says something along the lines of, “I don’t know how we did this to you.” But the truth is, almost everyone in the church thought sending me to ‘ex-gay’ therapy was the right thing to do. Love in Action came highly recommended. And the more I started focusing on the question, this totally reasonable question of how it could happen and how any parent could do this to his or her child, I began to see that only memoir could begin to address the question.

AA: You were nineteen-years-old in 2004 when your parents encouraged you to go to ‘ex-gay’ therapy. Has the church changed or become more sympathetic about members coming out since then?

GC: The church changed right after I left. But you have to keep in mind that when we talk about ‘the church’ we are really talking about a lot of different dominations in the area I grew up in. There was the Assembly of God and the Church of Christ, which I honestly don’t know that much about, but my Missionary Baptist church was very plugged into the ‘ex-gay’ movement at the time. Church leaders considered it the best option if your kid turned out to be gay. But right after my experience in 2004, this sixteen-year-old kid Zack Stark posted all the rules of ‘ex-gay’ therapy at Love In Action on his blog, and this act caused a huge protest. There’s also a This American Life piece about it featuring John Smid, the former director of Love In Action, that explains why Smid decided to put an end to the facility. The documentarian Morgan John Fox even made a documentary about Love In Action called “This Is What Love In Action Looks Like,” which talks about how those protests raised awareness and caused even the ‘ex-gay’ counselors to reconsider their stance.

AA: Do you have a relationship with God today?

GC: My relationship with God is highly in flux. Like I said in the memoir, prayer for me was really a place of comfort. Like I could just speak into my head and order the world in some way. Even when I thought I was speaking to God, I was really speaking into my head and making a litany of the important things of the day or the things I wished would happen in my life. I sometimes still pray, but I wouldn’t say that I have a direct relationship with a knowable god.

AA: What about your parents? Do they?

GC: Yes. My father is still a preacher. His congregation is growing. He has a soup kitchen now and it’s pretty successful. And my mom is still a preacher’s wife, but she is very much in support of me. She’s stuck in the middle.

AA: It seemed like those recorded conversations highlighted in Part Two of Boy Erased were very difficult to have with your mother and that she was overwhelmed with guilt.

GC: It’s getting a little easier now, but we almost can’t go a full conversation without apologies and crying.

AA: The end made me cry openly like a baby. I think a lot of people can relate to having a parent who wants him or her to be something else. What is your relationship with your father like today? Has he read the manuscript?

GC: My dad was really worried about his congregation finding out about the book. As you know from reading it, there’s an idea in the church that says that the sins of the father are passed down to the son, or that whatever is reflected in the son’s behavior must be some fault of the parents. Because of this idea, my dad was worried that the church would turn against him and vote him out. His church has to be a self-sufficient by next year. Up until this year the Baptist Missionary Association has funded his church, but this funding will be cut off next year when his church becomes a fully-functioning, self-sufficient organization.

My father and I had this fruitful phone call about his fear. I said, “I know you don’t want to talk about the book, and ‘ex-gay’ therapy is not something we have talked about much in the past, but I want you to know that I didn’t write any of this to make you feel bad or to paint you as a villain.” I said, “I tried to make you into a three-dimensional human being.” He didn’t really respond this, but my mom said he went into his office, closed the door, and cried for about an hour. That night, he got behind the pulpit and said, “My son has this book coming out that’s about gay stuff. If you need to leave the church I’ll understand, but I’m staying here.” That was a really big deal in our family because he had not yet acknowledged the book, though there were certainly plenty of rumors.

Recently, some weirdo at my dad’s church saw my Twitter account and told my dad that he really needed to read what was going on. My dad got on there. I think he might’ve read the Virginia Quarterly Review excerpt. I think he read more of what the book was about, and my mom said he was really upset and wondering if I was going to Hell again. Even so, we just talked right before this interview and he seems to be okay. We’re no longer at a stalemate. I would say we’re just at a really awkward phase.

AA: What happened to the girl that you call “Chloe,” your high school girlfriend? Does she know about the book?

GC: I contacted her on Facebook right before I was about to write about her, because I didn’t want her to be mad at me. She was nice for a couple of days and then she blocked me! I guess my posts were too gay! [Laughs] But her brother, “Brandon” in the book, is openly gay and lives in California somewhere. He’s always posting these cute drinking pictures with his gay friends. She’s also cut him off a little bit. She’s married to a guy who in every photo on Facebook has camo on and her two children are carrying guns. So that’s a lost cause. [Laughs]

AA: You also wrote about how literature saved your life. What were your favorite books and authors growing up?

GC: The electric ‘ah-ha’ moment for me was when I read The Scarlet Letter for the first time. It was both the literal and metaphorical value of that scarlet letter that made me think: Okay, people hate her based on what she looks like and who she is, and everyone in this town is wrong! It was amazing: Someone took the time to craft this narrative that lets me know that everyone in a town can be wrong about an issue. Also, Hawthorne is obsessed with his family history, as I am. In the beginning of The Scarlet Letter he talks about how he discovered an embroidered scarlet letter in the file room where he was working this government job. He learned that his family was part of the Salem Witch Trials. Their family name was actually Hathorne but he changed his name to Hawthorne so he wouldn’t be associated with the Hathornes, who were some of the people that killed all those women. He felt like he had a moral duty to write about what his family had done and what people like that can do. I only found this info out later when I became obsessed with the book, but there’s also a more literal connection to the genogram. Hester Prynne had an A on her chest for adultery, and they (Love In Action) made me write an A on my family tree as part of a “Moral Inventory.” It’s really obvious why I would love that book, though at the time it just came as a shock of recognition.

AA: You got your masters from Auburn and then went to University of North Carolina — Wilmington for an MFA. You could have attended grad school in a liberal city like New York or Los Angeles. Why did you choose to stay in the South?

There are people living in North Carolina who aren’t privileged and mobile, who can’t leave the state, so we decided, Fuck it! Let’s go!

GC: One reason is that Auburn paid for everything [Laughs]. The other is that the South is what I have always known. I guess in some ways it’s easier to exist in a liminal space. I’ve since lived in Ukraine and Bulgaria, both of which are not progressive in terms of civil rights. The South is familiar to me, and I feel like I know my purpose there. Part of my upcoming book tour is with Garth Greenwell, and we’re booked for three different dates in North Carolina back to back. Bruce Springsteen recently canceled a concert in protest of the North Carolina Anti-LGBT Bill, but Garth and I are both Southern boys and we both feel like our best work will be to go to the places that hate us and shove it in their faces. [Laughs] We actually agreed to book two more dates together in North Carolina after the law passed. Publisher’s Weekly recently published an article about how the laws are harming bookstores. There are people living in North Carolina who aren’t privileged and mobile, who can’t leave the state, so we decided, Fuck it! Let’s go!

AA: Why did you move to Sofia, Bulgaria?

GC: I moved to Bulgaria because I fell in love with a Bulgarian man. We met at a writer’s conference called the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation. She wrote The Historian, which was a big book about seven years ago. She uses her money to fund five English-speaking writers and five Bulgarian writers to go to the Black Sea and do a workshop. While I was there I met my boyfriend, but then we lived apart for a year while I was at UNCW. After I sold my book and it was under contract that first year, I moved to Sofia to be with him while writing the book and teaching English.

AA: I read your Acknowledgments page. You said that you sold your memoir before you had even written it. What was the publishing process like for you?

GC: That was so crazy. The publishing process for this book is something that infuriates people if I just tell it to them while they’re in the process of trying to publish something. I try not to talk about it often. It was one of those fairy tale stories. I was at AWP in Boston and had been invited to this dinner by a great short story writer named Kathy Flann. This was during the mini-blizzard, and we were getting snowed in. Some guy was holding court at the head of the table, mansplaining something, and I turned to the woman next to me and said, “What is with this guy?” She said, “Thanks for saying that!” She turned out to be Maud Newton, who writes these great book reviews and has a book on ancestry coming out soon and has a blog that’s been very popular. She has so many connections. She asked me what I was writing, and I told her about my essay. Then she asked me if I would like to go to an agent party with her to meet Julie Barer. I was like sure! I drank too much because it was open bar. Julie spoke to me, and very soon afterwards I sent one of the agents at Barer Literary a query letter, not knowing at all what I was doing. They asked to see more. I had like eighteen pages. I said I had everything basically written but I just needed to revise. [Laughs] I spent the next two weeks at UNCW not sleeping and writing what became the second chapter, The Plain Dealers, on their computers, sort of stealing my way into the computer building at night. I sent the chapter in, and right after that I signed with Julie. I wrote a proposal that summer on one hundred pages, which was then rejected by every house except Riverhead. It was sent to like thirty people!

AA: Do you think they were just afraid of it? I mean, I see this as a big deal book.

GC: I don’t know. Several big name editors like Lee Boudreaux were interested, but I guess they couldn’t sell it to the whole house. I have a different editor at Riverhead now, the fantastic Laura Perciasepe, but the editor who called was Megan Lynch. She’s great! She bought it on the proposal and two chapters, along with an experimental part, which is now Part Two, with my mom in it. I feel like I’m still very lucky!

AA: I was raised without a formal religion. My mother grew up Catholic, my father Jewish. We didn’t go to services regularly and holidays were for fun. Before I read Boy Erased, the concept of ‘ex-gay’ therapy was almost unfathomable. Why do readers like me need to buy your book and read it?

GC: There are two points I would like to make about that. I was thinking about why people should read my book when Riverhead was picking up the proposal, because I was worried that an editor might want to sand off the edges and make my story more palatable to readers. I wanted this memoir to be an odd document of that particular period of time in that particular version of America, an America that I believed was out to get me and the rest of the world. I thought that if this ‘ex-gay’ experience happened to me then the event wasn’t necessarily an isolated one. You can see this in current politics. Look at the North Carolina bill that just passed. Look at Tennessee. Look at Mississippi. This stuff is coming back. One of the things I say to my students when I’m teaching about civil rights issues is that it’s never a straight line of progression. In fact, these bizarre happenings are an essential part of our culture. It wasn’t so long ago that we had George W. Bush. It feels like it but it wasn’t. Even today crazy thinking controls a lot of legislature that gets passed in our country. I don’t want to sound inflated, but firstly I wanted my memoir to be a true document and secondly that if anyone found it ten or twenty years from now hopefully they would say, “What the fuck were they thinking?” [Laughs]

I’m tired of the type of memoir that just shows you its scars and wants you to feel sympathy for it. This is not that kind of memoir.

I started teaching The Crucible while I was writing the second half of Boy Erased, and I believe we’re still interested in that story and obsessed with witch trials because this is a strand of American history that’s still alive. What I didn’t want was for my book to become a trauma narrative or a healing narrative that would be touted as merely a testament to love. It’s not meant to be only an uplifting and inspirational piece of literature. I’m tired of the type of memoir that just shows you its scars and wants you to feel sympathy for it. This is not that kind of memoir. I wanted it to be a little scary.