Books & Culture

Hail Oblivion! The Apocalypse Book that Wasn’t

Jeff Jackson’s novella is both a phenomenal followup and companion piece to his debut, Mira Corpora

According to the mighty gods of Wikipedia, Novi Sad is an old, Serbian port-town that is located squarely on the banks of the Danube River. It was once an epicenter of culture, which earned it the nickname the Serbian Athens. How relevant or revelatory any of that information may be is up for considerable debate. That is to say, it’s pretty unclear (highly unlikely?) if the eastern European city of Novi Sad is the actual setting for Jeff Jackson’s phenomenal follow up and, in some ways, companion piece to 2013’s Mira Corpora. But that initial uncertainty and questioning of reality is important, if not integral to the world that Jackson is culling to the surface.

“Jackson paints a vivid and immersive portrait of a world on the brink.”

Novi Sad continues in much of the same tradition of Mira Corpora and Jackson’s short story, The Dying of the Deads (whose setting, Monrovia, is another real city in Liberia, though certainly not the setting for that piece). In many respects, all these pieces are cleaved from the same dark crystal and woven from the same dreamcloak.

The backdrop for Novi Sad is the end times, although the year is a bit vague. There is no evidence of the internet or cell phone or any of the culture of those devices and the world seems to have returned to a more primal state.

The ensuing Armageddon seems difficult to cope with for everyone except our main character, Jeff, who seems to have been on the run since he was a kid and, therefore, whose life was almost certainly already in a constant state of upheaval.

Of the group of scrappy survivors he has found himself with by untold means, we know that he has been alone and homeless long enough to see through the politics and semantics of group leader, Hank’s, diatribes of survival. The reader can almost sense that perhaps Jeff is using the group for refuge and doesn’t buy into the ideology.

Jackson paints a vivid and immersive portrait of a world on the brink, or over the brink, or so similar to our own that we must use words like that to distance ourselves from it. This is a world where “even the feral kids have famished from the streets, replaced by dogs prowling in loose packs, scrounging for half-digested scraps.”

Make no mistake, Jackson is showing us the Future of Now. He is gazing, as Ballard did, five minutes into the future to show us a world where the news grows increasingly bizarre with each passing day, where world leaders’ hunch in underground bunkers and bankers perch on window ledges as they cling to money. In short, he is showing us our future.

Jeff and his band of survivors aim to seal themselves off from this fucked world by making an abandoned hotel their shelter. They toast to the end times, “Hail Oblivion!” — and are then left to wait, something they are perhaps less than prepared for. They drink, they watch television, they take drugs, they play stupid games. They are us. We are them.

Jackson’s background as a playwright is ever-present in the book, in Hank’s grand language and gesturing, in the surreal and grand bombed-out setting of the abandoned hotel, in the arrangement of portable generators and gas cans gathered in the courtyard. This is particularly impressive considering the world of Novi Sad is almost entirely insular; whether it is within the hotel or the perspective of Jeff, who views conversation as “a sub-species of misunderstanding”. In many ways, the walls of Jeff’s body are akin to the walls of the hotel, both a protective and safe refuge from the world outside.

Like most good stories about a group of people who follow a charismatic leader, there is an inevitable mutiny. This one, however, is interrupted by the cataclysmic disaster they have all been waiting for.

Jackson’s end of the world is much like Eliot’s –there is no bang. In Jackson’s words, it ends mid-sentence. It leaves us feeling unsatisfied and without the cathartic bloodletting we’ve been taught to expect and, as a result, it makes me wonder, are we living through the end days now? If our world was ending, would we even know it? Would we even notice?

Part two begins with our crew looking for Hank. The world has come and gone but not much seems to have changed for our characters, save for the loss of their leader.

Their days mostly rotate around trips to the pier where the fishermen use their nets to bring in stray bodies from the river instead of fish or crabs. Jeff and his cohorts hope to see Hank’s body pulled up as some sort of closure so they can all move on. But that citing never comes.

Part two is intentionally aimless. The world has ended, but how can one look at it with anything other than a sort of indifference since our characters have survived? I suppose whether it is indifference or a defiance to move on is unclear, but to our characters that still live in the hotel and desperately are waiting for the return of a leader who will never come, what’s the difference?

With Hank gone, they must find strength inward; something not all the characters are particularly good at. One finally leaves the hotel after his idea to burn it down was met with laughter. Jeff tells us that in hindsight, he didn’t think the idea was all that crazy; he was just too preoccupied with some vague notion of loyalty to someone or something that he couldn’t quite place.

In short, this aimless afterworld leaves our characters desperate and lost. Without an apocalypse to prepare for or a leader to guide them, they seem unsure how to grapple with being survivors.

Part three flashes forward. Jeff is now alone in the hotel, his friends all gone- some dead, some split. Jeff is hanging up the clothes of his lost friends on the clothesline of the roof and allows the wind to fill their shape. At first he tells us he does it as a signal, but quickly he and the reader understand the ritual resembles more of a séance than a signpost, as it appears to be some desperate or sad attempt to conjure the presence of his lost friends.

The sadness and beauty of this moment hangs for just a second before Jeff quickly finds himself caught up in a proverbial comedy of errors. When Hank’s old flame shows up drugged out of her mind and mistakes Jeff for Hank, he plays along. Jeff isn’t even aware he is dressed in Hanks clothes and the ease with which he plays along becomes a fascinating and telling trait about the character from whose perspective we get much of the book.

“Make no mistake, Jackson is showing us the Future of Now.”

What seems to start out as playful soon escalates when Jeff follows the girl to a party on the other side of town. He gets his ass kicked but still manages to go back home with the girl, despite the array of pills they have each taken. Soon he realizes he cannot sustain the charade and leaves. He is not Hank and he could never be, and the revelations that have led to that understanding cannot be changed.

The appendix is truly fascinating and one of my favorite parts of the book. Jeff addresses the reader directly and describes photographs of the motley crew we have come to know; only the photographs are all blacked out. it’s a brilliant and beautiful section because each photograph tell us something about the character, how they are posing, where the photo was taken, but instead of showing it to us, Jeff, the character for whom language often seems to fall short, explains it to us.

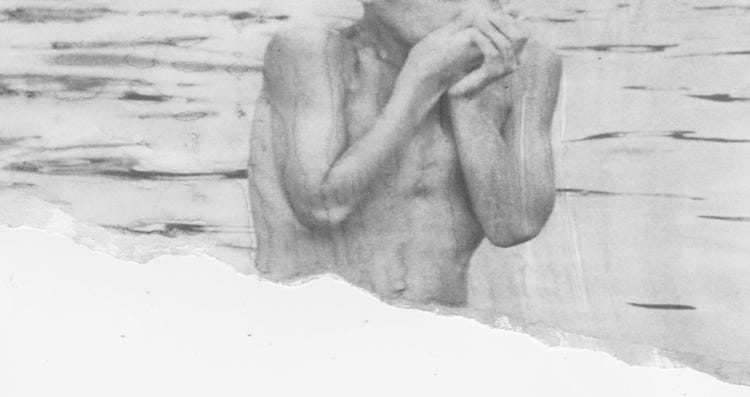

The entire book is brilliantly illustrated by artist and Kiddiepunk founder, Michael Salerno. The images are hauntingly beautiful — decaying buildings, teenagers with their eyes scratched out. Packaged together, this book acts as a sort of found object that is so cohesive and singular that at times it almost appears to be breathing.

Like all of Jackson’s work, Novi Sad is a truly singular and profound experience. It firmly roots you in the familiar while simultaneously transporting you to a soft, light-blue dream space. Much like the work of Lynch or even Harmony Korine, Jackson’s world is one that, despite all logic, you know must be true, not because it looks true, but because it feels true.