Books & Culture

Haunting Lincoln

George Saunders’ first novel is also his most complex and satisfying work to date

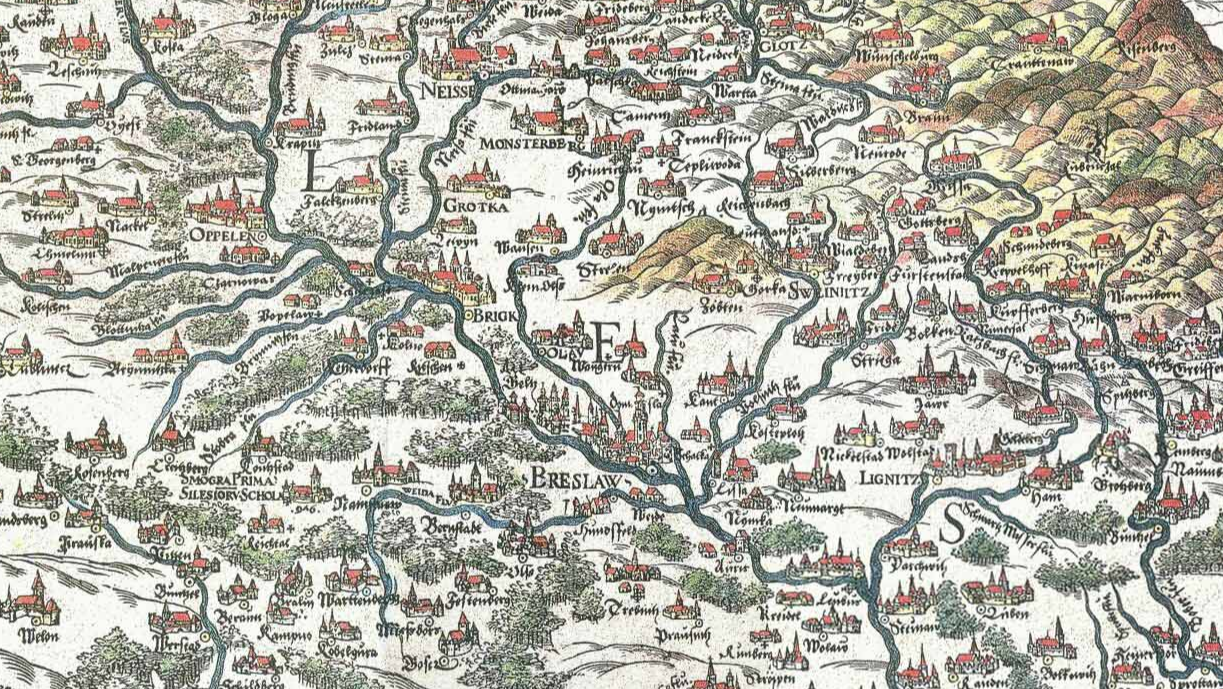

Lincoln in the Bardo takes place in February 1862, the month that brought the first major casualties of the Civil War, along with the death of Abraham Lincoln’s own 11-year-old son, Willie. At the time, rumors circulated of how the grieving president would return at night to the Oak Hill Cemetery crypts to cradle Willie’s body; Lincoln in the Bardo uses this image as its quasi-historical foundation. If, to you, the notion of a book built on a little boy’s corpse sounds depressing, that’s because it’s a depressing book. It’s also very fun: dramatic, witty, and unabashedly sentimental. What else would you expect from George Saunders, the Willy Wonka of American letters, who coats life’s cruel absurdities in a sugary glaze?

To be clear, Lincoln in the Bardo is a novel, but if you glanced at a few pages, you might mistake it for an oral history, the script to a radio play, or maybe one of David Shields’ anti-fiction bricolages. In some chapters, a chorus of historians and contemporary sources describe, from afar, a First Family at the intersection of personal and national crises. Some sources are authentic, some invented; Saunders never makes explicit which are which, though his playful little forgeries are often easy to spot. (“Nearly lost among a huge flower arrangement stood a clutch of bent old men in urgent discussion, heads centrally inclined,” for example, sounds a lot less like a 19th-century socialite than a 21st-century fiction writer.) Most of the book retains this chorus-form, but to more straightforwardly fictional ends, as a community of hapless ghosts fight to save Willie Lincoln’s soul.

In Lincoln in the Bardo’s afterlife — which is only ever called “the bardo” in the title — divine justice is dispensed with totalitarian arbitrariness, and souls are locked in their bodies’ moment of death. Willie’s two main interlocutors, Hans Vollman and Roger Bevins III, appear, respectively, with hideously swollen genitals and a dent in his skull, and as a many-eyed, many-limbed blur; the Rev. Everly Thomas “always arrives at a hobbling sprint, eyebrows arched high, looking behind himself anxiously, hair sticking straight up, mouth in a perfect O of terror”; one woman remains ever-blissfully oblivious to a pursuer’s incessant molestation. Elise Traynor, trapped to the cemetery fence, has it the worst. She arrived in the bardo “as a spinning young girl” about Willie’s age, but now she’s demented and grotesque, transmuting into images of ruin. This is one of the more sadistic diktats of this universe (or of God, or karma, or George Saunders…blame whomever you’d like), that if children stay in the bardo too long, they get stuck there, and their suffering compounds the longer they remain.

So how do the ghosts leave the bardo, in Lincoln in the Bardo? They choose, very Buddhistly, to let go of their earthly attachments (i.e., their desire to live). Then, with a “bone-chilling firesound” and a blast of light, they vanish. This “matterlightblooming phenomenon” petrifies the ghosts, most of whom are in deep denial about their mortality—which, incidentally, them about the worst companions imaginable for Willie, who, like Elise on the fence, is beginning to become trapped to his crypt. Complicating matters further is the 16th president, who returns to reenact the Pietá with his son’s dead body. After this embrace of fatherly love, Willie cannot bring himself to leave. The ghosts, almost all of whom have long since been forgotten by the living, are likewise bowled-over by this display of affection, even though they know what consequences Willie will face if he remains.

Weepy stuff, as you can see. Reading Lincoln in the Bardo might, at times, call to mind funeral dirges, throngs of ululating women. The book wears its mawkishness like a crown, and it works: isn’t grief, a huge emotion, best expressed hugely? Still, after the reader finds herself, 70 some-odd chapters after Willie dies, reading yet another account of how in his final days he was “suffering horribly,” she might feel like her nose is being rubbed in a tragedy — an actual tragedy, a real boy’s real death, deployed to raise the stakes of a ghost story. As Joan Didion says, writers are always selling someone out; one senses that this novel knows, at some level, that it’s selling out the real Willie Lincoln, so it overcorrects, insisting ad nauseum that the reader mourn him. But one can only listen to ululations for so long.

Lincoln in the Bardo’s other shortcomings appear to be borne of this sort of finicky impulse. (And no doubt its successes — its eminent readability, playful language, and unrelenting narrative momentum — arise from this trait, which could as easily be called perfectionism, as well.) For example, too concerned with closing every circle, Lincoln in the Bardo rambles on for a few more chapters after it should’ve ended. Or take the matter of slavery: it would be remiss for a novel set in Washington D.C. in the 1860s to fail to address America’s original sin. And the novel does address it, two-thirds of the way through, when “several men and women of the sable hue” meander over to Oak Hill from a nearby mass grave, demanding to “have their say.” Then they have their say, for eleven pages. One man wishes he could go back and murder his masters; another finds both solace and sorrow in his memories of “free and happy moments” (“On Wednesdays, for example, when I would have two free hours for myself”). Here, one senses the novel’s self-awareness again, that it knows all its major characters are white men, and it’s perfunctorily trying to compensate.

By the same token, why call this afterlife “the bardo”? Bardo is a Tibetan term that refers to the liminal space after death and before reincarnation (it’s often compared to purgatory in Roman Catholicism). Bardo Thodol, the Tibetan religious text known in the West as the “Book of the Dead”, refers to a “bardo of the moment of the death,” which seems to be represented in novel by the ghosts’ stuck positions. Likewise, the “matterlightblooming phenomenon” might be a nod to luminosity, “the clear light of reality” said to be the state of consciousness in death. But this sort of engagement is superficial at best, reference without contemplation. And furthermore, Bardo Thodol also says that the period between death and rebirth lasts only 49 days. Outside of its title, Lincoln in the Bardo skews far more Christian than Buddhist. Engaging with Christianity is understandable, probably unavoidable, being that we’re dealing with a cast of dead white antebellum men, and the 49-day tarrying period would inconveniently obliterate the narrative stakes. But still, paired with the quickie slavery dialectic, what we see is a thin veneer of multiculturalism, clearly well-meaning but little more than cosmetic.

However, the book does engage in a complex way with matters of faith, largely through the Reverend Everly Thomas, the lone ghost who knows he’s dead. Not only that, the Rev. knows he’s going to Hell, though he says he has no idea what mortal sins he committed, and the reader has no reason not to believe him. He fled from judgement, and now he’s laying low in the bardo. After his spectral troupe encounters some souls from Hell (but not the worst one, they insist), the Rev. says:

As I had many times preached, our Lord is a fearsome Lord, and mysterious, and will not be predicted, but judges as He sees fit, and we are but Lambs to him, whom he regards with neither affection nor malice; some go to the slaughter, while others are released to the meadow, by his whim, according to a standard we are too lowly to discern.

It is only for us to accept; accept his judgement, and our punishment.

Oh, but I was sick, sick at heart.

So much of Lincoln in the Bardo is nakedly pleasurable, even—especially—at its most depressing, but what a bleak view of the universe it has. Yes, it finds comfort in the commonplace joys of being alive (“Such as, for example: a gaggle of children trudging through a side-blown December flurry; a friendly match-share underneath some collision-tilted streetlight; a frozen clock, bird-visited within its high tower; cold water from a tin jug…”), but it forces its characters to suffer until they renounce these joys, to embrace terrifying uncertainty, to deny the world and explode into nothingness—with no assurance that their suffering will subside. The fleet-footed sentences, prodigious research, unabashed sentiment, and rollicking plot, in the end, are all glacé. Underneath is an acrid core, which makes Lincoln in the Bardo George Saunders’s most complex and satisfying work to date.